THE NEW CRITERION, May 2022

On “The Utopian Avant-Garde: Soviet Film Posters of the 1920s” at Poster House, New York and “Thornton Willis: A Painting Survey, Six Decades, 1967–2017” at David Richard Gallery, Chelsea and Harlem, New York.

Is this bad timing for a show on Russian art and design? “The Utopian Avant-Garde: Soviet Film Posters of the 1920s,” which opened at New York’s Poster House museum in late February, suggests otherwise.1 Here is an eye-opening exhibition of fifty works from a century ago that lays bare Russian aspiration in graphic form. Created during the first flush of enthusiasm for the new Bolshevik state, these innovative posters speak to the progressive spectacle of early Sovietism—and the hundred years of failure that has followed, with its aftershocks in devastating evidence today.

Alexander Rodchenko, Poster for Film-Eye, 1924, The Ralph DeLuca Collection. Photo: Poster House.

These works are also simply dazzling to see. The posters were designed to startle, bringing to the Russian street a taste of such cinematic innovations as montage, unexpected angles, stop-motion animation, and extreme closeups as they vied for popular attention. Informed by a new faith in utopian architecture and engineering, and drawing on tenets of Constructivism, Suprematism, and Productivism, these posters reflect the influence of early Soviet design over much of modern art.

Even before the Russian Revolution, Nicholas II, the modern world’s ill-fated tsar, was quick to grasp the potential of the motion picture. Just five months after their first picture show in Paris on December 28, 1895, the Lumière brothers sent their cameraman Camille Cerf to Saint Petersburg. Cerf filmed Nicholas’s coronation for a ninety-three-minute cinematic feature, among the first documentaries of its kind. Sensing the power of movies to reach his dispersed and largely illiterate population, the tsar ordered the importation of production supplies and initiated a Tsarist Chronicle newsreel series. Major French studios, such as Pathé and Gaumont, established offices in Moscow both to create and distribute film. With a burgeoning domestic appetite for movies, the Russian film industry was soon well underway.

As the First World War upended the supply chain of movies from the West, a domestic Russian cinema grew up around the country’s new movie palaces. The Russian Revolution and Civil War then placed their own extreme pressures on the production and distribution of film—theaters were nationalized, making the sale of raw celluloid illegal, and eventually all cinematic and artistic expression outside the supervision of the Soviet state was criminalized. By the early 1930s, the creative suppression was total. Still, for a brief period in the 1920s—under a more inchoate revolutionary state—Soviet movie culture prospered. Propagandistic domestic films and adulterated “bourgeois” foreign productions competed for screen time. The Russian audience was hungry, including for mass entertainment.

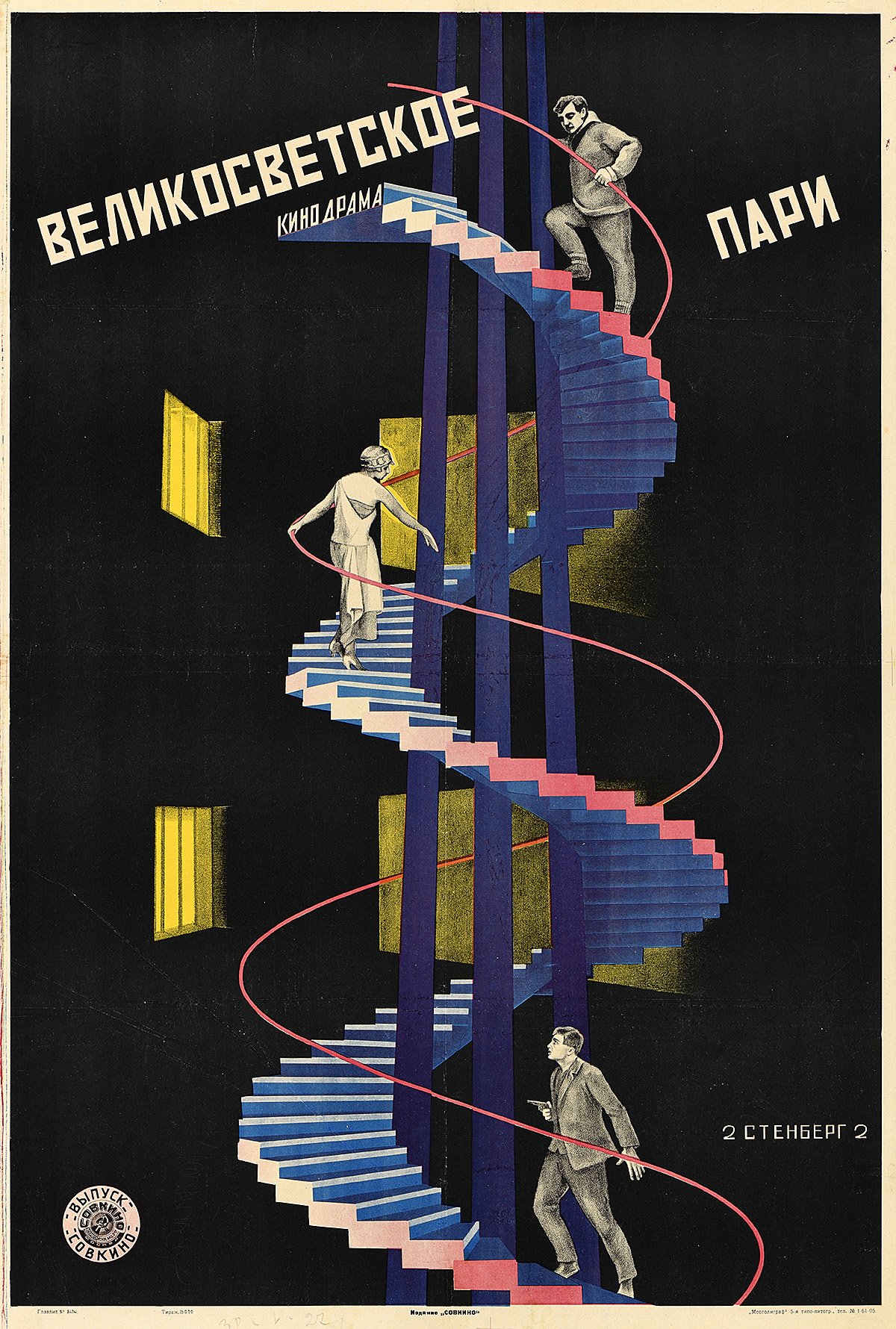

Vladimir Stenberg and Georgii Stenberg, Poster for High Society Wager, 1927, The Ralph DeLuca Collection. Photo: Poster House.

At the leading edge of this strange Soviet quasi-industry, the movie poster became the prime vehicle for selling these films. Fifty of these posters are now on display at Poster House, all on loan from the Ralph DeLuca Collection. It is remarkable that any have survived at all. They were almost all created with limited time, limited resources, and limited knowledge of the movies they were advertising. In the fast-paced climate of 1920s Russian cinema, they were designed, printed, and posted in a day and covered over in a week. Yet from what has remained, it is clear that these pressures combined with the visual idealism of the early Bolshevik state to encourage their graphic innovation. “In this chaos,” writes Angelina Lippert, the chief curator of Poster House, “a vibrant, idealistic group of young artists and intellectuals enjoyed a brief period during which they could use their talents to build a new Russian culture.”

What this exhibition lacks in an independent catalogue, it makes up for with wall labels that well describe the posters on display and the films they depict. If anything, the exhibition should send you home to look up these early Russian films. Out of copyright, they now reside on such YouTube channels as rvision. Be sure to pause on Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Camera, an astonishing silent documentary from 1929 that depicts the kinetic street life of Kyiv, Kharkiv, Moscow, and Odessa. In his opening credits, Vertov bills his film as an “experiment in cinematic communication of real events, without the help of intertitles, without the help of a story, without the help of theater, a truly international language.” Or consider the “Odessa staircase,” Sergei Eisenstein’s famous scene from Battleship Potemkin. Perhaps the finest example of propaganda ever put to celluloid, this famous story of a 1905 mutiny against tsarist overreach calls out for rescreening today. Alexander Rodchenko’s poster for the 1925 film, with Potemkin’s twin guns reaching out like the steel arms of an incipient Soviet man, is a visual highlight of the show.

Alexander Rodchenko, Poster for Battleship Potemkin, 1925, The Ralph DeLuca Collection. Photo: Poster House, New York.

For all of their appreciation by cinephiles today, such early Soviet films were often less popular with Russian audiences than the adulterated Western films from America, England, and Germany that made their way east. This, despite the fact that the West didn’t always send their best. Soviet authorities also changed up Western film plots to conform to the party line, inserting alternative intertitles. They might even include a live political speech or recording, bookending a movie with agitprop to justify the playing of a Western show. “In reality,” writes Lippert, “people—particularly the urban poor—just wanted to be entertained.” That meant that “almost anything of note, from factory openings to seasonal festivals, found its way into Soviet cinema, always accompanied by a dynamic poster.”

As she describes them, many of the films that circulated in 1920s Russia, from both East and West, sounded like they were lifted from an off week of the Moscow TV Guide:

A six-reel satire in which a British aristocrat poses as a butler in order to win affections of an American businessman’s saxophone-playing daughter. (The Business Man, 1929)

The young son of a revolutionary obsessively holds onto a pipe belonging to his father—but this gesture eventually results in his own death. (The Communard’s Pipe, 1929)

The plot follows a young Jewish couple escaping life in a shtetl by becoming actors in a traveling Yiddish theater. (Wandering Stars, 1928)

Based on the groundbreaking sociological work The Sacred Scarab (1909) by feminist writer Else Jerusalem, in which she documents the lives of Vienna’s fifty thousand prostitutes, The Green Alley . . . is reshaped into a tragic love story between a waitress at a brothel and a doctor’s son. (The Green Alley, 1928)

A documentary celebrating the triumphs of modern agricultural practices through mechanized farming. (Giant to the Virgin Soil, 1930)

It was just as well that Soviet poster designers often knew little about the movies they were promoting. Such ignorance gave them license to move away from the character-driven storytelling of Western design and its “bourgeois sentimentality.” Instead they experimented with the broader possibilities, and limitations, of color lithography. One of those limitations was the size to which they could print the image of a film still. Unable to enlarge them to the full size of a poster, they often employed a series of smaller, related images as a montage to animate the storyline, as Anton Lavinsky did for his poster of The Death Ray (1925). Or they might trace out a larger photographic projection in lithographic pencil, as Alexander Rodchenko did for Film-Eye (1924). Or they might resort to graphic abstractions, such as Nikolai Prusakov’s tetrahedron for The Second Exhibition of Film Posters (1926).

Vladimir Stenberg and Georgii Stenberg, Six Girls Seeking Shelter, 1928, The Ralph DeLuca Collection. Photo: Poster House.

The most successful posters often used a combination of these lithographic techniques. Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg’s High Society Wager (1927) finds its characters running up an abstracted spiral staircase. Semyon Semyonov’s Turksib (1929) grafts the solarized face, hands, and shoes of a shouting worker onto railway signals. The Stenbergs’ Six Girls Seeking Shelter (1928) turns a pattern of alternating rectangles, like the flicker of the movie projector, into a screen that covers the girls’ bodies. For The Great Tragedy of a Small Woman (1929), Nikolai Prusakov dismembers a pair of human figures and an automobile grille to create a visual chaos that even crashes into the typography.

For all of the intelligence throughout this exhibition, its finest movements come at the conclusion, in its explanation of the “death of the avant-garde poster.” In 1930, the directory body Soyuzkino was founded to centralize control of all cinematic production and distribution. Foreign films were banned a year later. In April 1932, the Soviet Central Committee banished independent artistic groups entirely. The golden age of Soviet art, film, and graphic design had lasted less than a decade. “Unlike his immediate predecessors,” writes Lippert, “Stalin did not share the view that art could be used as a means of transforming society. Instead, he believed that its sole purpose was propaganda.” She concludes:

While design historians celebrate the incredible posters in this exhibition, it is important to remember that they were produced during a time of social upheaval and terror. Millions of people were murdered under the Soviet regime; millions more were stripped of their property, separated from their families, and exiled to labor camps for the remainder of their lives. Today, these posters allow access to a period of Russian history in which chaos and political uncertainty were briefly outshone by the progressive idealism of some of the greatest graphic designers of the twentieth century.

A major survey of the paintings of Thornton Willis, now on view at David Richard Gallery across its two New York locations, serves to illustrate the long influence of Russian design, for one, on the history of modern painting.2 This ambitious exhibition also makes a case for the inclusion of Willis in the pantheon of American abstract art. With over twenty major works on view from the artist’s collection, some of them not shown outside the studio for several decades, “Thornton Willis: A Painting Survey, Six Decades, 1967–2017” brings together highlights from each of Willis’s series of abstract compositions. David Richard’s Chelsea location includes a tight arrangement of medium-size paintings, while the gallery’s Harlem venue gathers Willis’s largest works, topping out at over ten feet wide. The survey coincides with “Exploring Thornton Willis,” an exhibition at the Sarah Moody Gallery of Art at the University of Alabama, featuring a selection from Willis’s recent gift of over two dozen paintings to his alma mater.

Thornton Willis, Starstrux, 2007, Oil on canvas, David Richard Gallery, New York.

Working across more than six decades, Willis has been consistent in his abstract exploration of the basic tensions between figure and ground, push and pull, color and contrast, and surface and depth—visiting and revisiting his visual language. Observing his work over twenty of those years, I have learned to look to his edges to appreciate how his fields of paint rub against each other to create their dynamic tension.

In their simplicity, Willis’s more basic abstractions, such as his wedges, lattices, and zig-zags, are approached as particular challenges of visual animation. Bold compositional decisions, from paint handling to color contrasts to the placement of a single corner or edge, are what set these works in motion. With Willis’s more complex abstractions, such as his cityscapes and kaleidoscopic prisms, the challenge is not to create tension but to maintain it. Underdrawing, pentimenti, and paint splatter all signal the energy of that final dynamic, of artist and object, as Willis folds his compositions together to await our own unpacking—ensuring his designs do not land too firmly on one thing or another. The suspension of Brooklyn Bridge (1993), the shock of Brown Zinger (1983), the portal of Full House (1981), the mechanics of Locomotive (1999), the radiance of Starstrux (2007)—the full energy of these paintings is now ready to be felt and seen.

“The Utopian Avant-Garde: Soviet Film Posters of the 1920s” opened at Poster House, New York, on February 25 and remains on view through August 21, 2022.

“Thornton Willis: A Painting Survey, Six Decades, 1967–2017” opened, in part, at David Richard Gallery, Chelsea, New York, on March 30 and remains on view through May 13, 2022. The second part of the exhibition opened at David Richard Gallery, Harlem, New York, on April 4 and remains on view through May 13, 2022.