THE SPECTATOR, WORLD EDITION

On the family gun club

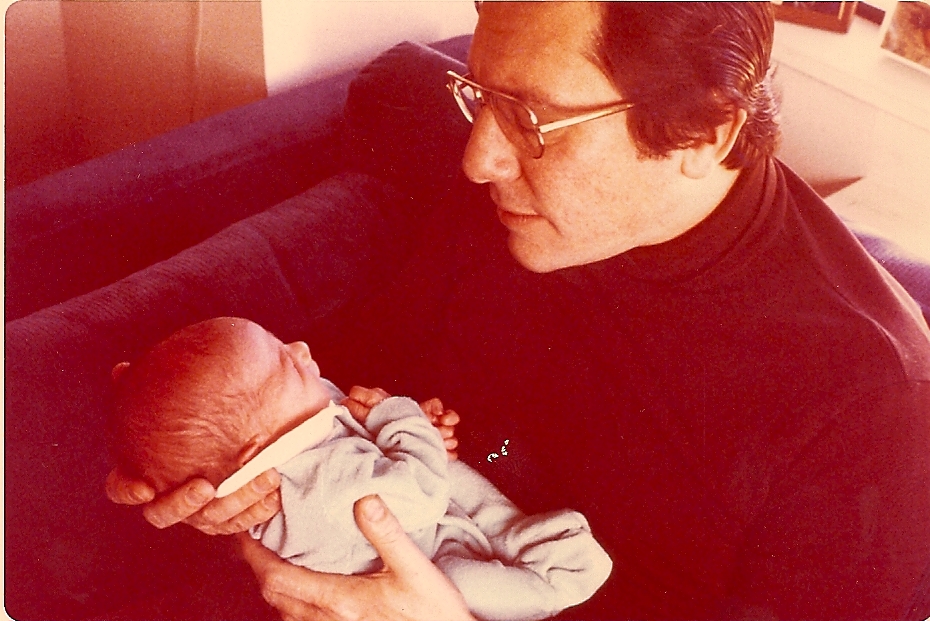

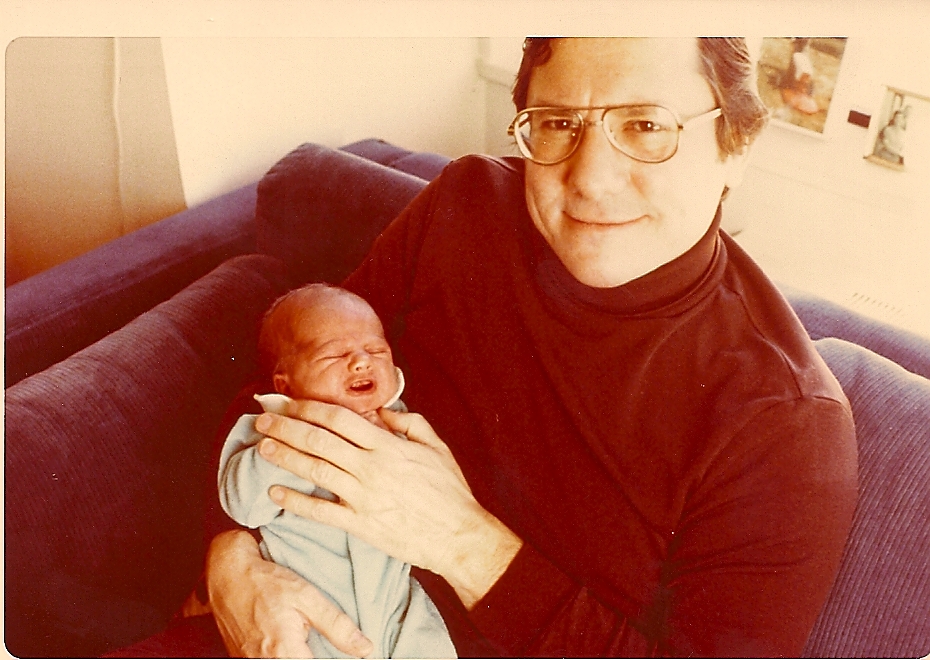

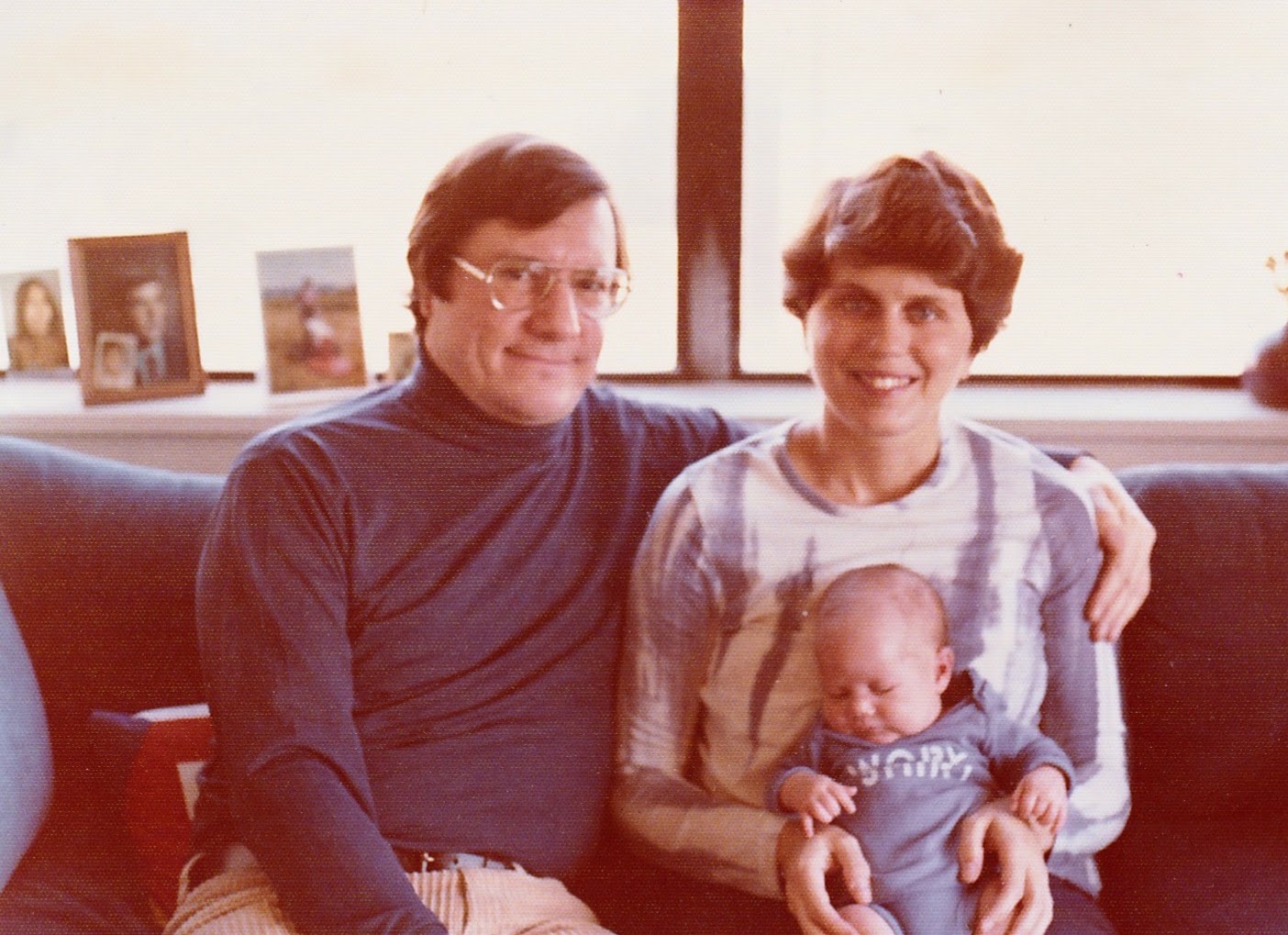

In his late-middle age, my father cultivated more of the interests of the old neighborhood. His kitchen overflowed with pasta makers and deli slicers. His prep table was taken over by a home wine-making operation; we ate our meals beside a glass carboy as it bubbled up fermented gas. And scattered about the living room, tucked in the bookcases and stashed behind the coffee table, he positioned an array of locked cases and bags containing a growing collection of rifles, pistols and shotguns.

The acquisitions that came to fill our Upper West Side apartment mainly came from the shops around Little Italy. Home winemaking was once common among Italian Americans. So too was a well-developed sense for gun culture. There was a time when riflery and marksmanship were encouraged across America, after all. Look at any high school yearbook from a century ago and you will likely find a picture of the student gun club. For Americans of Italian descent, an affinity for firearms was a patriotic necessity. The Risorgimento, the fight for Italian reunification, remained a recent memory. In the 1850s, after a first unsuccessful effort, the Italian general Giuseppe Garibaldi had regrouped in Staten Island, bringing with him his partisan supporters, including, so the story goes, my great-great-great-grandfather, a Piedmontese from Cuneo in northern Italy. Loyalty, combat readiness and virtù, have long remained in the blood.

In our family lore, the Papal states and the Napoleonic empire were all variously to blame for giving Italy the boot. Our quarrel with Rome went back to the tale of Ugolino della Gherardesca, the Count of Donoratico and our Pisan progenitor, who became caught up in that unfortunate Guelph-Ghibelline business of the 13th century and was framed by a Popish plot. The denouement found Ugolino deposited in the lowest circle of Dante’s Inferno, where at least he got to nibble on his betrayer, Archbishop Ruggieri.

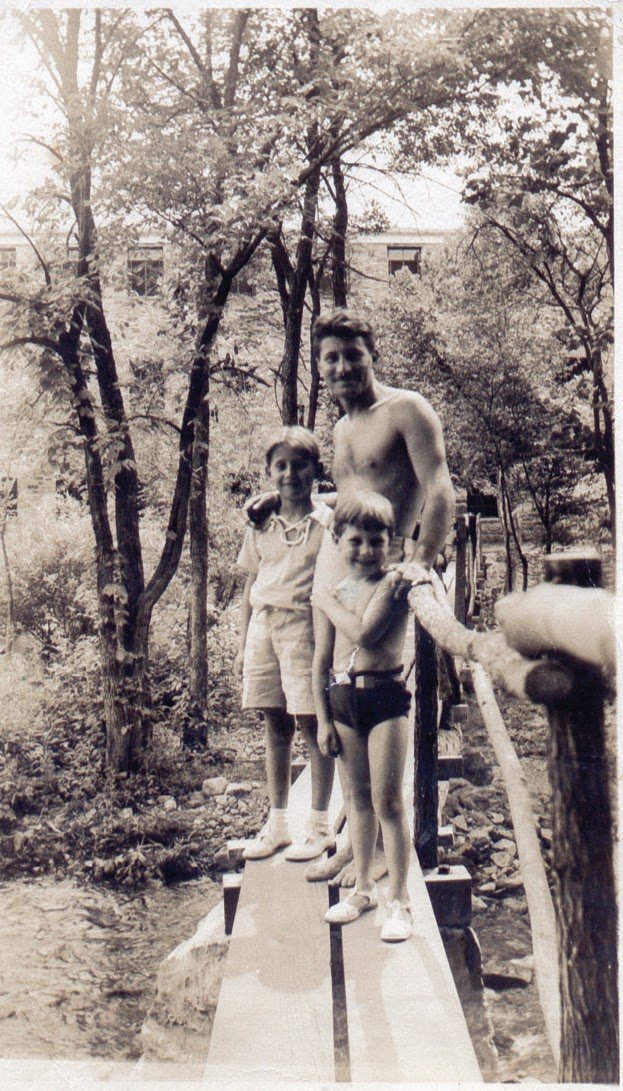

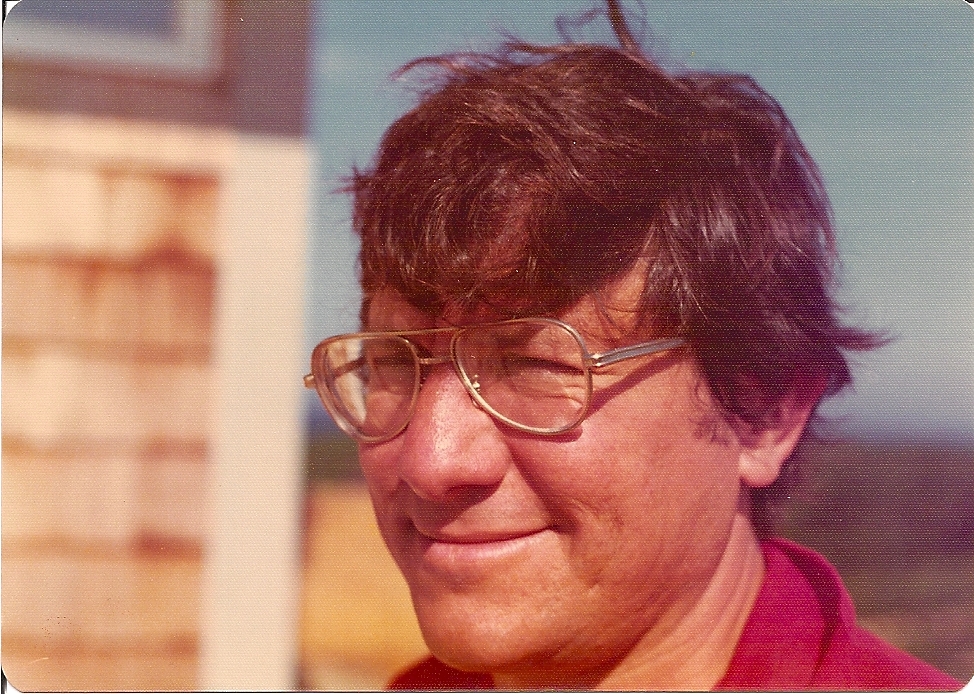

Such enmities were slight compared to the family loathing for the Austro-Hungarians and their incursions into Italian lands. At the outset of World War One, my great-grandfather and namesake Giacomo Panero, an American banker, voluntarily returned to Italy to join the Alpini, the mountain division of the Italian army. He successfully pushed the Germans out of the southern Dolomites— in the process, we were told, adorning his high-alpine bunker with Hun skulls. His Italian army portraits, in cloak and alpine hat, still adorn my bookshelf.

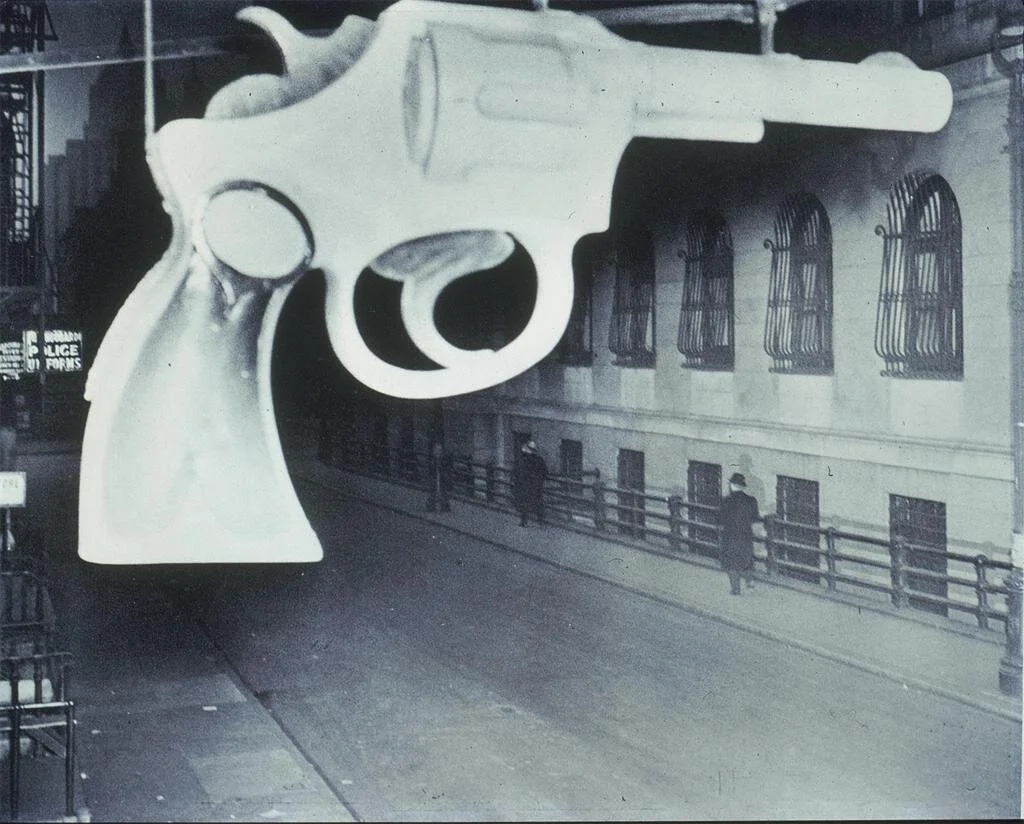

When I reached the age of 16, it was time for me to join the family ranks. My father brought me downtown to John Jovino Gun Shop to acquire my first firearm. The old gun shop was a small storefront in an alley behind the palatial former police headquarters at 240 Centre Street. An oversized pistol hung from its sign, a famous urban marker that made cameo appearances from Weegee to Serpico. Founded in 1911, the store was the oldest gun shop in New York, if not the country, before it was finally cut down by the Covid closures of 2020. Back in the early 1990s, as city residents turned to self-defense at the height of the last New York crime wave, business was booming.

Gun enthusiasts are some of the nicest people you will meet. The owners were happy to see a first-time family walk through the door. We selected a Marlin 882 SS, a .22 caliber Winchester magnum rimfire rifle. The gun’s bolt action, still to this day a joy to slide, must have reminded my father of Giacomo picking off those Germans high in the Dolomites. We mounted it with a magnifying scope. To this purchase my father added a .22 target pistol and .357 Magnum revolver.

It should be said that New York City’s gun laws are among the most punitive in the country — for law-abiding citizens, at any rate. Acquiring the license to safeguard a firearm in your home and to transport it in a locked bag to a range is an ordeal. Even during the Nineties crime wave, licensing your firearm was nearly as onerous as today, and my father did it by the book. At the time, it required months of paperwork, background checks and precise postal money orders that had to be filed with a clerk in the bowels of One Police Plaza. Unless you are in a business that transports large sums of cash or cash-equivalents, you can forget that concealed-carry license.

Fortunately at our range it was a different story. Since the owners ‘sold the bullets to the police’, the atmosphere in our tidy range, tucked two stories below the streets of Lower Manhattan, was more laissez-faire. I was more than free to practice with my father’s firearms. I could also try out any of the Glocks or other pistols they kept behind the counter. Want to test out a 12-gauge pump action shotgun against the ‘thug’ target? Fire away. The range came stocked with food catered from Chinatown and, understandably, quickly became my high-school hangout.

In his retirement, my father left the city for freer gun states. His collection came to include a vintage Browning Auto 5 and a Remington 581S. When my wife came to meet him, he gifted her a snub-nosed .38 special in the manner of Clemenza handing one to Michael Corleone, just without the tape on the butt.

In 2003, when the Smith and Wesson company debuted its .50 caliber five-shot revolver (the Model 500), my father was first in line to purchase one. He lived and died an avowed atheist, but he believed in stopping power. The gun was designed to stop a bear in its tracks. It could also ‘put a bullet through an engine block’, he liked to say. When we finally tested it together at a sandpit in the free state of Vermont, the pistol felt like a piece of personal artillery. A flaming shockwave emanated from the end of its barrel and expanded in a cone of heat and light. ‘This gun is your inheritance,’ he told me, more on target than I cared to realize. It was the last time we shot together.