ART & ANTIQUES

April 2009

Unsentimental Education

by James Panero

Brandeis University’s plan to deaccession its entire art museum causes a furor.

Brandeis The students of Brandeis University, in Waltham, Mass., have been enrolled in a crash course in museum ethics and the realities of the art market. On Jan. 26 the trustees voted unanimously to sell the permanent collection of the school's 48-year-old Rose Art Museum, which houses one of the finest collections of modern and contemporary art in New England, valued in 2006 at about $350 million.

Brandeis is facing financial difficulties—its endowment dropped from $712 million to $540 million in six months and several of the university's top supporters were victims of Bernard Madoff. Against the wishes of the museum's director, Michael Rush, and his board of advisers, the trustees identified what they thought would be a valuable and easily liquidated asset that was not essential to the university's core mission of education. "We don't want to be in the public museum business," explained president Jehuda Reinharz to The Boston Globe.

Since the Rose has functioned for nearly five decades as a teaching museum deeply integrated into the school's curriculum, Reinharz's critics have wondered out loud whether Brandeis intends to remain in the education business at all. "If Brandeis stands by its mission statement... then the Rose Art Museum is as important to the school as its library," wrote three high-profile curators who are Brandeis alums--the Nasher Museum's Kimberly Rorschach, the Metropolitan Museum's Gary Tinterow and the Whitney's Adam Weinberg--in an open letter to the university.

"Art cannot be treated as a liquid asset," says Rush. "History will record this as a desperate action that flies in the face of all intellectual and ethical standards." It would also be another alarming reminder to donors and patrons that museums can no longer be trusted as stewards of their own permanent collections.

Reinharz has attempted to weather the massive public relations backlash by admitting that he mishandled the announcement and by assuring his faculty and student body that there is no time-table for the sale of the art.

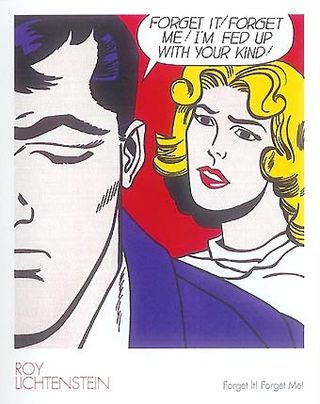

In the current economic climate, many observers have wondered if the proposed sale even makes economic sense, especially considering that most of the works are postwar and contemporary. At the top of the market, a few of the Rose's prime pieces--Andy Warhol's 1964 Saturday Disaster, Roy Lichtenstein's 1962 Forget It! Forget Me! and Robert Rauschenberg's 1961 Second Time--could have fetched tens of millions each.

Would a Rose sale realize much less than the 2006 valuation and adversely affect established price benchmarks? Not necessarily, says dealer Richard Feigen. "If the quality is what I think it is, particularly with that provenance, then it won't adversely affect the market. The whole art market hasn't turned down just for certain trendy contemporary art," he says. "Prices are still very high for things that are fresh to the market, like the Brandeis collection would be. There's money out there looking for a place to park and doesn't know where to go."

Yet even if Brandeis manages to cash in on its permanent collection, Feigen cautions, the damage to the institution would be just as permanent. "Were I a trustee I would be opposed to this. The museum is part of the character of the university and the fabric of patronage in this country. The paintings won't be recoverable, nor will Brandeis be able to recover its reputation."