James writes:

Thomas P. Campbell, the Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, has issued an "important message" responding to the criticism I and others have raised over the ticketing policies at his and other public-private institutions in New York City. The Director's affable but ultimately defensive message tells me the Met has heard the criticism but hasn't listened to it.

Two weeks ago in the New York Daily News, I wrote an editorial titled "It's Time to Free N.Y.'s Museums." Here I argued that "institutions on public land, supported in part by public funds," are designed to serve the public good. According to the Department of Cultural Affairs, this means providing "cultural services accessible to all New Yorkers”--regardless of their ability to pay. "Unfortunately," I wrote, just as "many members of the CIG [an alliance of public-private institutions] have improved their facilities over the years through better administration and aggressive fund-raising, they have also become far less accessible to ordinary people" through confusing ticketing policies designed to extract a greater toll at the turnstile.

The Metropolitan is now party to two lawsuits over the "recommended" language of its tickets, claiming that not all museum-goers understand the nuances of the suggested price. My survey of other NY's public-private institutions reveals that many of them impose even more restrictive and confusing rules at the turnstile.

In his response, Campbell says "our costs—everything from guards to insurance to publications—have increased." The Met plans to defend its admissions policy "vigorously."

The Met is clearly facing a growing crisis over its ticketing policies. The museum therefore could and should be using this opportunity to lead the way towards creating better admissions policies to the city's cultural institutions. At the Met this could mean bigger, better signage--in multiple languages--about the meaning of its "recommended" admissions fees. It could mean a new ad campaign in city neighborhoods about the availability of great art for a penny a subway ride away. Considering the Met draws significant taxpayer support and other benefits from city government--just under $25 million a year in direct city support and passed-through costs such as electricity, according to the report of its CFO--the Met could propose a new initiative to give free access to city residents, which would compel other institutions to do the same.

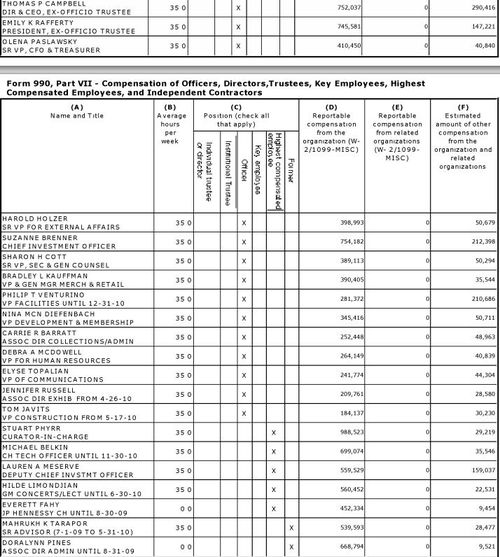

Instead, the Met has doubled down on its current policy. The reasons are predictable. Campbell is right that his museum needs the turnstile revenue to cover increasing costs. These costs include the salaries of Met employees. As I mentioned to Fred Dicker on "Live from the State Capital" (available at the top of this post), according to the Met's publically available tax returns from 2011, Mr. Campbell earned over $1 million in salary and benefits. At least ten Met employees bring home over half-a-million dollars a year while working (according to their own tax returns, at least) 35 hours a week . Here is a breakdown of those salaries from the museum's 990 tax filing. What if the Met were to post these numbers at their ticket gates?

This need for greater turnstile revenue may be one reason why the museum has turned to mounting critically panned, populist exhibitions such as "Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists, Fifty Years." It's also why the Met has brought on a DJ as its new artist in residence and decided to open on Mondays.

But big business can be bad business at a non-profit designed to serve the public good. The ever-increasing demands of what I call the museum-industrial complex was the topic of my essay in The New Criterion a year ago, titled "What's a Museum?"

On the letter of the law, there may indeed be nothing to the Met lawsuits. But that doesn't mean the city's public-private institutions are fully living up to the spirit of their public mandates. When you are earning $1 million a year, indirectly in part through the taxpayer dime, it can be hard to understand the museum goer who can't afford $25 or regret the one who didn't know to pay less. It takes three hours working at minimum wage to earn enough to pay the Met's full "recommended" price. Working 35 hours a week, Tom Campbell earns that same amount every two and a half minutes.

Throughout their history, the Met and the city's other public-private institutions have benefited from the generosity of New Yorkers. Their admissions policies should be as equally generous in return.