THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

December 16, 2016

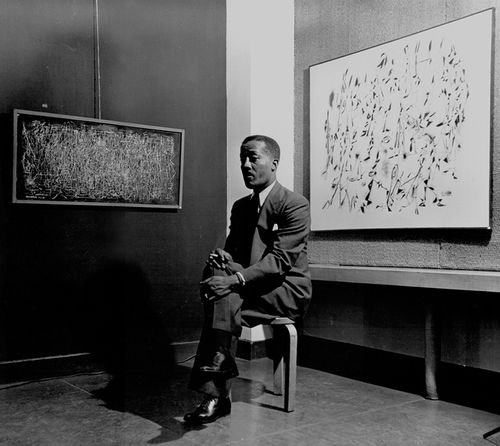

‘Procession: The Art of Norman Lewis’

By James Panero

On the artist who bridged the gap between the Harlem Renaissance and the New York School, on view at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts through April 3, 2016

‘Procession: The Art of Norman Lewis” at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts is impossible to see without experiencing multiple emotions. The first is exhilaration, over Lewis’s artistic vision; his command of materials, color and line; and the freshness he brings to our art-historical understanding. The second is regret, over what has been to this point our general ignorance of a singular American artist; more than 35 years after his death in 1979, Lewis is only now receiving his first full retrospective. The third emotion is frustration, over the forces that have long conspired to keep Lewis from greater attention—a specific bigotry that goes beyond race to an unspoken prejudice against artists who dare to work outside of expected limits. “Almost forty years after his death,” curator Ruth Fine writes in her richly documented and provocative catalog, “Norman Lewis’s art continues to challenge conventions of painterly practice on many levels, and to remain under-known.”

Born in New York to Caribbean immigrants in 1909, Lewis bridged the gap between the Harlem Renaissance and the artists of the New York School with an innovative and largely self-taught style. With the conscience of a social realist, he came to paint as an Abstract Expressionist, drawing inspiration from a circle of artists that included both Romare (“Romy”) Bearden and Ad Reinhardt. Such boundary-crossing did not go down well in his lifetime. It still doesn’t. By art critics and his fellow black artists, Lewis was often considered insufficiently focused on the realities of the street. But he was also seen by the wider art world as being less than fully engaged in the innovations of the downtown scene.

Now with 90 works assembled from both public and private collections, Ms. Fine makes the case that Lewis, in fact, fully inhabited both worlds. He did not just move from one to the other. He interwove sources and styles in a hybrid way that deserves special recognition, as in “American Totem” (1960), a white-on-black abstraction of Klan hoods. “A true Harlemite,” in the words of artistJack Whitten, only Lewis could also occupy a seat at the table for the closed-door conversations of the Abstract Expressionists in the Artists’ Sessions at Studio 35 in 1950.

Lewis cast a wide eye from the very start. The most revelatory comparison comes early in the exhibition, covering a period when Lewis made weekly visits to the Museum of Modern Art. A set of four pastels, from 1935, are realistically rendered still-lifes of African masks. “Fantasy,” painted just a year later, captures both the abstract technique and musical spirit of Kandinsky.

Using bleeds of color cut through with black marks, Lewis applied this Kandinsky-like style to his street scenes, such as the lively “Hep Cats” (1943) and visions of destitution and police brutality, which brought him early acclaim. Yet two years later, he abandoned overtly recognizable imagery, and the subject matter that was expected of him as an uptown artist, to pursue abstract experimentation.

It wasn’t that he lost his commitment to racial issues. Rather, he believed that protest was better demonstrated on the picket line, which he joined for racial causes, than through his paintings. “Political and social aspects should not be the primary concern; aesthetic ideas should have preference,” he proclaimed.

His art is therefore “difficult to describe in summary fashion,” Ms. Fine concedes. “Its development neither followed a linear path, nor ever arrived at a single signature style.” This is now made all the more apparent through an exhibition that brings his full range together. For some, the result may further complicate his reputation. It is true that Lewis’s art, and abstraction by black artists in general, has recently received some important museum attention. Yet the fact that this current exhibition, according to Ms. Fine, was turned down by multiple venues in New York, Lewis’s hometown, speaks to a continued prejudice against artists who refuse to be siloed. New York’s loss is Philly’s gain. This show, which includes a side exhibition of Lewis’s printmaking in PAFA’s famous Frank Furness building next door, will go on to Fort Worth, Texas and Chicago.

At PAFA, the exhibition begins and ends in a lobby filled with Lewis’s monochrome paintings from the late 1960s on. This large-format work emerged after he moved from Harlem to a loft on Grand Street in 1968. The yellow “Afternoon” (1969) feels like a bucolic idyll. The red “Confrontation” (1971) beside it could be a fiery Klan rally.

In these paintings of calligraphic marks and washes of color, Lewis captured very different moods. In each, he found a “spaciousness that began with acceptance of the sky and the distancing sea,” as Bearden once observed. Diaphanous forms and scrims of color swirl like a fog, distancing us from the ant-like figures in his compositions. For Lewis, this remove from oppressive realities liberated his work. Whatever their subject matter, his paintings reveal there is no color barrier to transcendence.

Mr. Panero is the executive editor of the New Criterion.