THE NEW CRITERION, May 2024

On the falsification of Lincoln Center’s history.

During the high dudgeon of the Black Lives Matter movement, New York’s Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts joined the chorus of handwringers with a particular twist. “In our 60+ year history, we have not done nearly enough. It is part of our job now to help change the status quo,” read the center’s “Message on Our Commitment to Change.” Lincoln Center’s multiple concert venues may have been shuttered by the pandemic. Its institutional constituents, which include the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic, and the New York City Ballet, were facing the prospect of millions of dollars in losses. Yet as its first priority, the center determined to dedicate itself to

Telling the story of Lincoln Center from our beginning, in its truth. The displacement of Indigenous, Black, and Latinx families that took place prior to the construction of our campus is abhorrent. We may never know its full impact on those dispossessed of the land on which Lincoln Center sits. But only by acknowledging this history can we begin to confront the racism from which our institution has benefited.

With the blood-and-soil essentialism of today’s identity politics, the commitment to “confront[ing] the racism from which our institution has benefited” and “telling the story of Lincoln Center from our beginning, in its truth” fell in line with the new progressive rhetoric of land acknowledgments, colonialist dispossession, and supposedly unearthed legacies of systemic oppression. The diagnosis also presented an opportunity for Lincoln Center’s younger leadership, remote-working members of a new generation of the managerial class, to treat their organization’s “abhorrent” injustices against “Indigenous, Black, and Latinx families” with their own patent mixture of tinctures, elixirs, and balms. How much of this “truth” is in fact true was beside the point. By design, their cure would be worse than the disease.

For the racial pathologists, in the case of Lincoln Center this sickness was malignant, metastasizing, and neglected for far too long: the center’s four-block complex owed its existence not just to Peter Minuit’s alleged swindling of Mannahatta for sixty guilders back in 1626, but also to the supposed destruction of a vibrant black community known as San Juan Hill some three centuries on. This culturally vital neighborhood of residences, businesses, and theaters, where Thelonious Monk lived and James P. Johnson developed the Charleston, was targeted in the 1950s by no less than Robert Moses for one of his largest projects of urban renewal. Such “slum clearance,” scattering seven thousand families and eight hundred businesses, paved over those “Indigenous, Black, and Latinx families,” as the leadership of Lincoln Center now represents its origin story, with white travertine and white culture.

Coming clean with these supposed injustices, Lincoln Center focused its post-pandemic programming not on Mozart or Stravinsky as it once might have done, but on turning its land acknowledgment into a multistage extravaganza. In 2022, commissioned by Lincoln Center in collaboration with the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Public Art Fund, the organization plastered a 68-by-150-foot mural called San Juan Heal at the corner of Broadway and Sixty-fifth Street across the northern façade of David Geffen Hall—formerly known as Avery Fisher Hall and, originally, Philharmonic Hall. Here the artist Nina Chanel Abney mixed symbols referencing ragtime and jazz alongside such phrases as “homage,” “honor,” and “urban renewal?”

Nina Chanel Abney, San Juan Heal, 2022, Latex ink & vinyl mounted on glass, David Geffen Hall, New York.

Geffen Hall’s inaugural opening night with its resident orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, then featured a new “immersive multimedia work” called San Juan Hill: A New York Story. Created by Etienne Charles, this piece brought together, according to its billing, “music, visuals, and original first-person accounts of the history of the San Juan Hill neighborhood and the indigenous and immigrant communities that populated the land in and around where Lincoln Center resides.”

To make the story more explicit, Lincoln Center and the New York Philharmonic arranged for a graffiti crew known as the ex vandals to paint a mural for the center’s Amsterdam Avenue façade. Conceived by a musician and tagger known as “Wicked Gary” Fritz, the work presented the black historical figures of San Juan Hill on the left, a depiction of the modern Lincoln Center plaza on the right, and a wrecking ball crashing through the middle. “This was a thriving Black community that they took out to bring in Lincoln Center,” Fritz explained to Ebony magazine at the unveiling.

A year later, Lincoln Center launched an online “hub” on its institutional website, called “Legacies of San Juan Hill” and dedicated to “interrogating our role in this history.” Here we can read of the “old, long disgraced story, the one in which benevolent city fathers swept in to rescue the city from slums and blight.” San Juan Hill “may have been run down, a source of hardship and deprivation, but the cure was worse than the curse,” continues one article. “Clearance and rebuilding scattered neighbors, broke apart fragile social networks, uprooted working class communities, destroyed jobs, targeted people of color for removal, and deepened racial segregation.”

Lincoln Center’s latter-day struggle sessions have played into a new media environment in which race-based narratives are an editorial imperative. “Before Lincoln Center, San Juan Hill Was a Vibrant Black Community,” went one headline in The New York Times. “A vibrant neighborhood known as San Juan Hill, which was home to many low-income Black and Latino residents, was razed to make way for the center’s construction,” went another article. Whatever the historical reality or the artistic merits of the San Juan Hill initiative, Lincoln Center banked its post-pandemic recovery on a narrative of its own abhorrence, developing programming and even a new campus plan around its “original sin” of race-based displacement. The one problem with such self-abnegation is that Lincoln Center’s historical record turns out to be far less loathsome than what its leadership represented, and even exculpatory of the crimes to which they now confess.

When Black Lives Matter becomes a marketing strategy, facts offer little impediment to “truth.” In the case of Lincoln Center, this new battle of San Juan Hill has ultimately been a story of conflation, exaggeration, and wishful thinking. The history of Lincoln Center and the neighborhood that came before it both deserve genuine appreciation, observed beyond the hothouse of race-based managerialism.

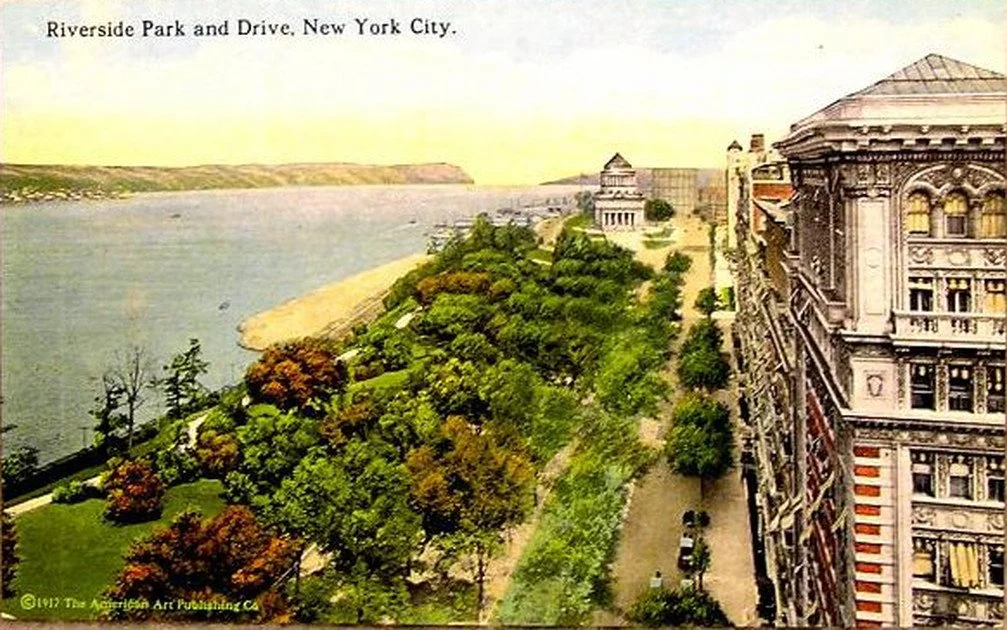

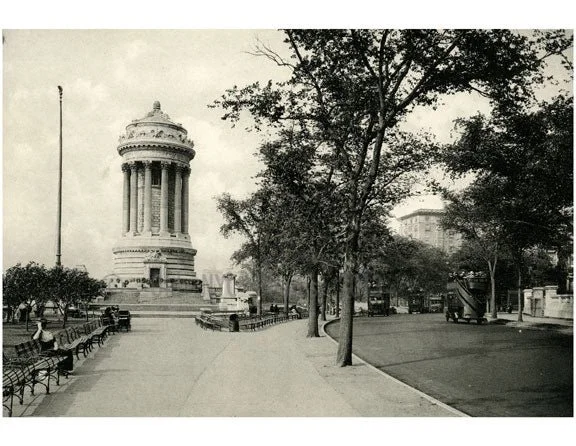

There indeed was a time when San Juan Hill—an area roughly defined as Manhattan’s far West Sixties, backed up against the New York Central Railroad’s sprawling Sixtieth Street Yard along the Hudson River—was a nexus of black New York. The bohemian energy that enlivened this neighborhood’s small theaters and nightclubs also attracted artists to the Lincoln Arcade, a loft building and theater at Sixty-Fifth Street and Broadway where the Juilliard School now stands. Robert Henri, Milton Avery, Stuart Davis, and Marcel Duchamp all passed through its studios. For nine months in 1908–09, the playwright Eugene O’Neill even lived there in George Bellows’s basement studio, basing his 1914 play Butter and Bread on the experience. To its credit, articles on Lincoln Center’s “Legacies of San Juan Hill” web hub explore this history in greater detail.

An image from San Juan Hill prior to Lincoln Center’s development. Photo: Lincoln Square Slum Clearance Plan, 1956.

But the cultural height of San Juan Hill came and went soon after the turn of the century. Manhattan’s own Great Migration saw black New Yorkers moving north from Greenwich Village through this West Side neighborhood on the way to Harlem. The “old law” tenements that filled out San Juan Hill’s narrow lots were made illegal after the city’s new code provisions of 1901 mandated greater setbacks for air and light—one explanation for why many black New Yorkers chose to move out of these overcrowded blocks. The advent of single-room-occupancy residences (after city housing law changed in 1939 to allow sros) and the conversion of several tenements into illegal business spaces further diminished the neighborhood’s housing stock. Garages, repair shops, gas stations, and utilities were intermixed into these blocks as extensions of the automobile row that still runs along Eleventh Avenue. Finally, centered among Irish, Italian, Polish, and other ethnic enclaves, the neighborhood became besieged with gang violence. The nickname of San Juan Hill, applied to an area that was officially known as Lincoln Square and Columbus Hill, may have been a reference to the black veterans who settled there after the Spanish–American War. Just as likely, the name came out of the ethnic warfare that famously inspired the musical West Side Story (which was filmed at the northern end of San Juan Hill just before demolition).

By the time New York turned its attention to redeveloping this section of the West Side, Robert Moses was not the only one who saw its deteriorating conditions and future potential. A decade before Lincoln Center ever took shape, the historical black center of San Juan Hill was leveled under Mayor Fiorello La Guardia to build Amsterdam Houses, an integrated housing project to the west of what is now Lincoln Center that opened in 1947, originally for veterans of the Second World War.

Proposed location of the Lincoln Square Project. Photo: Lincoln Square Slum Clearance Plan, 1956.

By the 1950s, thanks to the Federal Housing Act of 1949, cities across the country were using and often abusing eminent domain to tap into federal funds for slum clearance. The Lincoln Square Renewal Project of 1955 is remarkable not for what it cleared—seventeen decrepit blocks between Sixtieth and Seventieth Streets—but for what was created in its place: not another urban highway as was cut through many other municipalities, but rather a Manhattan campus for Fordham University, a new headquarters for the American Red Cross, four thousand units of middle-income housing, and a campus for multiple performing arts organizations of world renown.

For an evenhanded account of its creation and endurance, Beacon to the World: A History of Lincoln Center, by Joseph W. Polisi, the former longtime president of the Juilliard School, ably updates Edgar B. Young’s Lincoln Center: The Building of an Institution of 1980.1

A preliminary design for the opera house at Lincoln Center, by Wallace K. Harrison, 1955. Photo courtesy of Columbia University.

“A persistent problem with the Center’s legacy is manifested in the ‘original sin’ it committed in the 1950s of displacing thousands of families living in the Lincoln Square neighborhood,” Polisi begins. “As with most retrospective historical scenarios, evaluating through a revisionist lens the decisions made at the birth of the Center may be a pointless exercise.”

At the time of demolition, the New York City Planning Commission determined that the neighborhood of Lincoln Square had become “clearly substandard and unsanitary . . . a blighting and depressing influence on surrounding sections contributing to gradual deterioration of the Upper West Side.” “Maintenance of buildings was neglected, building code violations were numerous, and fire hazards were great,” notes Young. “By 1955, the entire area was in an advanced state of decay” and “one of the city’s worst slums.”

Substandard living conditions identified by the slum clearance committee. Photo: Lincoln Square Slum Clearance Plan, 1956.

New York City had identified the neighborhood of San Juan Hill for demolition and redevelopment long before the concept for a performing-arts center took hold. The idea for Lincoln Center only emerged after several of the city’s performing arts institutions found themselves in need of updated venues at the same time. The Metropolitan Opera had long ago outgrown its original home at Thirty-ninth Street and Broadway, an opulent Gilded Age venue but one with a limited back of house. Rockefeller Center and Columbus Circle were both considered as sites for relocation before Robert Moses approached the opera for his renewed Lincoln Square.

At the same time, the private owners of Carnegie Hall, the home of the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Society, at Fifty-Seventh Street and Seventh Avenue, had plans to tear down their storied venue and replace it with a high-rise office tower. The Philharmonic was sent scrambling after the landlords informed the orchestra its lease would not be renewed after its expiration in 1959. Finally, the New York City Ballet, part of City Center along with New York City Opera on West Fifty-fifth Street, was on the lookout for larger venues in order to stage George Balanchine’s ambitious ensemble works.

Proposed boundary map of the Lincoln Center Project. Photo: Lincoln Square Slum Clearance Plan, 1956.

As representatives for what would become Lincoln Center’s first three constituent organizations came together under the leadership of John D. Rockefeller III, the concept of a major new performing-arts center took shape and grew. The Juilliard School, then at West 122nd Street, and the special music collection of the New York Public Library, then located in the library’s main branch, were soon brought in as essential components for music education and research. Constituents for theater, film, chamber music, bel canto opera, jazz, and dance education eventually coalesced into the nearly dozen organizations that make up today’s Lincoln Center campus.

Under the Federal Housing Act of 1949, cities could draw on federal funds to purchase deteriorating neighborhoods through eminent domain and then sell the land for redevelopment at a discount. The difference between the purchase price and the sale price was known as the “land write-down,” for which the federal government financed two-thirds of the difference and, in the case of New York, the city and state split the remaining costs.

The groundbreaking ceremony for Lincoln Center Plaza, 1959. Photo: LIFE Photo Collection.

It is true that controversy surrounded the Lincoln Square Renewal Project at the time of demolition, but not for the creation of Lincoln Center. Instead, preservationists feared the loss of the Philharmonic would expedite the destruction of Carnegie Hall. Only at the last moment, even as its resident orchestra moved out, was the venue remarkably saved as a world-class home for visiting artists thanks to the violinist Isaac Stern, who convinced the city to purchase it. Legal challenges to the Lincoln Square plan primarily focused on the separation of church and state as it applied to the proposed campus of Fordham University, a Jesuit school, slated for the parcel to the south of Lincoln Center. The Supreme Court eventually dismissed this challenge to eminent domain in 1958.

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts came together to function as the umbrella organization for its constituents as well as their benevolent landlord. The new nonprofit also became responsible for the demolition and redevelopment of its then-three-and-a-half-block campus. As the center took ownership of 188 existing buildings with 1,647 occupied units and 383 commercial tenants, it aided in the relocation of its residents and businesses. Many of those moved out of their office spaces were not dispossessed family-run operations but rather federal agencies housed in one of Lincoln Square’s modern buildings, at 70 Columbus Avenue, roughly on the site of what became the New York State Theater, now known as the David H. Koch Theater. Built as the twelve-story headquarters for the Uppercu Cadillac Corporation in 1927, by the 1950s this loft building was owned by Joseph P. Kennedy, who rented its floors to the Immigration and Naturalization Service and the Atomic Energy Commission. Given this family connection, it should come as little surprise that the city paid a premium for its appraisal and demolition.

Census on minority populations conducted New York Slum Clearance Committee. Photo: Preliminary Report on the Lincoln Square Project, 1956.

While the city lavished funds on the Kennedy clan, Lincoln Center kept close tabs on the residents it helped relocate through the redevelopment plan. Most of them remained in Manhattan, with nine hundred families staying on the Upper West Side. A study of the first 742 relocated revealed that they moved into larger quarters, all with up-to-date sanitary conditions. Most notably, for all of the “abhorrent” claims of the “displacement of Indigenous, Black, and Latinx families,” the census conducted by the Slum Clearance Committee of those relocated to create Lincoln Center revealed a population that was, in fact, overwhelmingly white: 75 percent of those displaced were white, 24.5 percent were Puerto Rican, and just 0.5 percent black. As it turns out, Lincoln Center’s latest racialized tort has been nothing more than a false confession.

Regardless of its ethnic breakdown, the redevelopment of a decrepit San Juan Hill into Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts indeed proved to be the “unparalleled cultural opportunity” that the New York City Planning Commission first envisioned, one that illustrates the bold, high-minded actions of the post-war city at its best. The site’s master plan, under the architect Wallace K. Harrison, took inspiration from Michelangelo’s Piazza del Campidoglio on the Capitoline Hill in Rome.

It is true that, in the extensive use of travertine marble, which is porous and absorbs water, Lincoln Center’s stone facings have fared far worse under New York’s freeze–thaw cycles than they would under the Italian sun. The center’s International Style architecture—designed by Harrison (the Metropolitan Opera House), Philip Johnson (the New York State Theater), Max Abramovitz (Philharmonic Hall), Eero Saarinen (the Vivian Beaumont Theater), Gordon Bunshaft (the Library and Museum of the Performing Arts), and Pietro Belluschi (the Juilliard School and Alice Tully Hall)—has also aged poorly, set off from the city streets in an austere, windswept design.

Lincoln Center Plaza under construction, 1964. Photo: Bob Serating Photo © Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

“Lincoln Center is a triumph of city planning,” wrote Myron Magnet in the Fall 2000 issue of City Journal, dedicated to reimagining the arts campus. “But as architecture, oh dear. The Center was deplorable, as critics recognized from the start.” A campus refresh by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, completed in 2010, did much to lighten the imposing complex along Sixty-fifth Street and extend Alice Tully Hall up to the angled street line of Broadway, but the bandshell at Damrosch Park, on the southwest corner of the campus, has never succeeded, just as the sides of Johnson’s State Theater remain an unarticulated travertine mass.

The center’s performance venues have faced their own challenges. The Metropolitan Opera House has too many seats but too little lobby space. The New York State Theater, renovated and renamed the David H. Koch Theater, may be well turned out for ballet but remains flat-footed for singers or orchestra, in part accounting for the fall of New York City Opera, which shared the space with City Ballet. Finally, Philharmonic Hall has been such an acoustical failure that it has been redone (and renamed) multiple times. Its latest iteration, as David Geffen Hall, solved many of the sonic challenges but destroyed the elegance of its public spaces, sourcing garish upholstery more in line with a bus terminal and slathering its surfaces with theatrical lighting, all in the name of presenting a more “inclusive” atmosphere.

Philharmonic Hall, 1963. Photo: Lincoln Center for Performing Art.

The synergies that might have been expected from the close contact of many arts organizations have also, just as often, led to internecine conflict. The profligate Metropolitan Opera helped bully City Opera out of existence and has long set itself apart from its neighbors while antagonizing its own audience with aggressive contemporary stagings. Before this latest renovation, the New York Philharmonic even explored a return to Carnegie Hall and the abandonment of Lincoln Center entirely. Most significantly, the umbrella organization of Lincoln Center has more than once been at cross-purposes with its constituents, promoting its own messaging and programs that can be in competition with the presenting organizations.

In their storied histories, the center’s famous constituents have nevertheless sustained and championed the performing arts while also truly revitalizing their surrounding community, including what remained of San Juan Hill. It is noteworthy that the childhood home of Thelonious Monk, in the Phipps Houses on West Sixty-third Street, was spared by the development of both Amsterdam Houses and Lincoln Center and survives to this day. The famous jazz pianist performed numerous times at Lincoln Center, beginning just a year after it opened, recording a live album at Philharmonic Hall in 1963. Late in life, Monk moved into an apartment in Lincoln Towers, in one of the high-rises built as part of the redevelopment plan. Due to these affinities, Monk liked to call his neighborhood not San Juan Hill or Lincoln Square or even the Upper West Side but simply “Lincoln Center.” Similarly, after Nina Simone started performing regularly at Lincoln Center in the late 1960s, she moved into another of the new apartment towers, in the same building as the vibraphonist Lionel Hampton—and also where I grew up. Finally, Jazz at Lincoln Center, a constituent organization founded in part by Wynton Marsalis in 1987 and located in the Time Warner Center since 2004, has done more to sustain the musical culture of San Juan Hill than any facile “commitment to change.”

Lincoln Center Plaza, 1965. Photo: Suzanna Faulkner Stevens.

Under the leadership of Henry Timms, Lincoln Center’s young British-born president and chief executive from 2019 until this year, Lincoln Center has merely updated its antagonism toward its constituents for the woke age. In 2021 Timms brought on Shanta Thake, a concert programmer from the Public Theater downtown, as the center’s chief artistic officer. Thake, whose full name is Shannon Shanta Thake-Kriegsman, may be of Indian-German descent, but she plays the race card as her ace in the hole. As their first order of business, Timms and Thake canceled “Mostly Mozart,” the center’s long-running summer festival. Thake pledged to “really confront our past head-on as we move into the future” by “opening this up and really saying that this is music that belongs to everyone”—implying, of course, that Mozart does not belong to everyone.

In the place of Mozart, the new administrators installed a ten-foot-wide disco ball above the plaza fountain and two hundred flamingo lawn ornaments. They also hired rappers, pop groups, and an LGBTQ mariachi band for their new summer performance series. “I’m more in the world of the downtown aesthetic of edgy, in your face, heavily transgressive stuff that comes from an emotional place,” Thake explained of her taste to The New York Times. “I’ve seen people dressed as chickens, covered in baby oil, dancing to the latest pop song.”

In 2023, it was announced that Louis Langrée, the summer festival’s director for twenty-one years, would be replaced by the thirty-year-old conductor Jonathon Heyward. “The next chapter for the orchestra doubles down on these successes and aims to further Shanta Thake’s broader artistic vision in service to all of New York City,” read the press announcement, “continuing to break down traditional artistic silos.” Plans for the coming summer include a “symphony of choice” concert, with audience members “curating” the program by popular vote, and an exhibition about depression tied to the mental health of Robert Schumann.

The Oasis Dance Floor, 2023. Photo: Lincoln Center for Performing Arts.

Lincoln Center now finds itself at a moment when the Metropolitan Opera, which under Peter Gelb has pushed progressive programming, continues to withdraw emergency funds from its endowment to cover sagging ticket sales and exorbitant operating losses—$40 million this year, $30 million last year. At the same time, Timms has pledged to open up the Lincoln Center campus architecturally to the tenants of Amsterdam Houses, to the west across Amsterdam Avenue, as a top priority. Just how much these residents will help fill out the opera’s dismal numbers remains to be seen, but it is noteworthy that the center’s existing staircase to Damrosch Park, from Amsterdam Avenue and Sixty-third Street, has remained locked through his tenure.

At the groundbreaking for Lincoln Center on May 14, 1959, President Dwight D. Eisenhower took a shovel to the campus’s future plaza and praised the center’s “stimulating approach to one of the nation’s pressing problems: urban blight.”

Here will occur a true interchange of the fruits of national cultures. From this will develop a growth that will spread to the corners of the earth, bringing with it the kind of human message that only individuals—not governments—can transmit. Here will develop a mighty influence for peace and understanding throughout the world.

The triumph of Lincoln Center has been to champion the best of our cultural patrimony. Over half a century, the project has fulfilled its promise by bringing the highest standards of classical music, ballet, opera, theater, film, and jazz to four city blocks in order to promote a “true interchange of the fruits of national cultures.” This has been the full legacy of San Juan Hill, now topped by an astonishingly ambitious and farsighted cultural achievement.