The New York Post, December 21, 2025

Why New Yorkers from all walks of life can put a gun on their holiday wish list

All I want for Christmas is a snub-nosed .38. Some .38 Special ammunition would be nice too. This holiday season, we should all be thinking of our firearms wish list.

A year ago, I never thought I would be one of those rare New Yorkers to navigate the city’s byzantine gun laws. Nor did I quite anticipate the peace of mind that comes with firearms ownership.

But I did it, earning my own license to carry a concealed pistol. I now practice weekly at the range just down the block from my office with my own registered revolver. You can do it, too.

Sure, we’ve heard the stories of onerous regulations, invasive questioning and endless delays. Compared with much of the country, the application process remains a burden. But I am here to tell you it is no longer impossible. As I found, it can even be a rewarding experience. And if you want that Centennial-style hammerless Airweight in your stocking, you first need a license to carry it.

James Panero never thought he’d be one of those rare New Yorkers to navigate the city’s byzantine gun laws — but the process has gotten easier thanks to the Supreme Court. Tamara Beckwith/NY Post

My story began when I inherited an old service revolver from my father, Carl. A New York-based architect, one who had worked on designs for the World Trade Center and JFK Airport, he had taken to firearms when I was a teenager in the 1990s. He enjoyed the sport and comradery of the range, which he said reminded him of his time in Army basic training. He also saw it as a means for some father-son bonding and a reconnection with our Italian roots.

James Panero visits Ground Zero in 2014 with his father, Carl, who worked with Minoru Yamasaki as senior staff architect designing the World Trade Center. Courtesy of James Panero

I well remember the day he first took me to John Jovino Gun Shop. The storied retailer shuttered after 109 years during the 2020 lockdowns, but at the time, the store in Little Italy was thriving as it sported an oversized pistol hanging from its sign. Dad had me pick out my own bolt-action .22 rifle. He then slipped next door to resupply his homemade winemaking operation, another Italian pastime. At an upscale range near Wall Street, now long defunct, he shot his pistol while I practiced my aim with the small, rimfire rifle. All the while, a five-gallon glass carboy of red wine fermented in our highrise West Side apartment.

Decades later, when the time came to transfer his gun, a blued .357 Magnum manufactured by Smith & Wesson in the 1960s, I paid my first of many visits to the Westside Rifle and Pistol Range. Operating out of a basement space on West 20th Street since 1964, the range is an enduring lifeline for city gun owners. Here you can take training classes, join its shooting club, use its services as a federal firearms-licensed dealer (known as FFL) or simply try out one of its .22 rifles (no license required).

I have done it all. But first, I sat down with Westside’s owner, Darren Leung. “I am amazed we survived,” he said of his holdout range in the heart of Gotham. “But by the good grace of God and some great members, we’re still here.”

James brings his father’s gun — now his — to the range in a locked case. Tamara Beckwith/NY Post

Leung went on to explain the consequences of the landmark 2022 Supreme Court ruling in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen and what it meant for gun licensing in the city.

He also noted the uptick in interest in personal firearms following the 2020 riots, the attacks of Oct. 7, 2023, and the all-too-routine evidence that you cannot always rely on others to protect you and your loved ones. “Better to have a gun and not need it than to need it and not have it,” said Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the Russian founder of the Jewish Defense Organization and famous Zionist. That might well be the motto here too.

Back in my father’s day, most city gun owners could only expect to receive what was known as a premise permit. That meant you could take your firearm, unloaded in a locked container, to and from the range, and that was it. The Bruen decision changed that.

James’ story began when he inherited an old service revolver from his father. Tamara Beckwith/NY Post

Before Bruen, New York required its firearms applicants to show what it called “proper cause” to receive an unrestricted license. This effectively meant only diamond dealers and cash couriers could obtain anything beyond a premise permit. In 2022, the Supreme Court thought otherwise.

“We know of no other constitutional right that an individual may exercise only after demonstrating to government officers some special need,” wrote Justice Clarence Thomas, delivering the scathing opinion of the court in Bruen.

“That is not how the First Amendment works when it comes to unpopular speech or the free exercise of religion. It is not how the Sixth Amendment works when it comes to a defendant’s right to confront the witnesses against him. And it is not how the Second Amendment works when it comes to public carry for self-defense.”

With the high court ruling that the “Second and Fourteenth Amendments protect an individual’s right to carry a handgun for self-defense outside the home,” tens of thousands of new firearms applications flooded in.

James practices weekly at the range just down the block from his Manhattan office with his own registered revolver. Tamara Beckwith/NY Post

Leung suggested to me that the premise permit would likely be phased out. New Yorkers should now apply for concealed carry. The NYPD licensing division handles all applications through its website. The system is an improvement over the old paper forms and the need for exact postal money orders hand-delivered to One Police Plaza. I should also add that the NYPD licensing officers who reached out to me as my application was in process were all friendly and professional.

Nevertheless, the online application has many, many steps, and it is best approached in stages. The biggest hurdle of the application process is the 18-hour training class. But here what might have been a challenge proved to be a highlight.

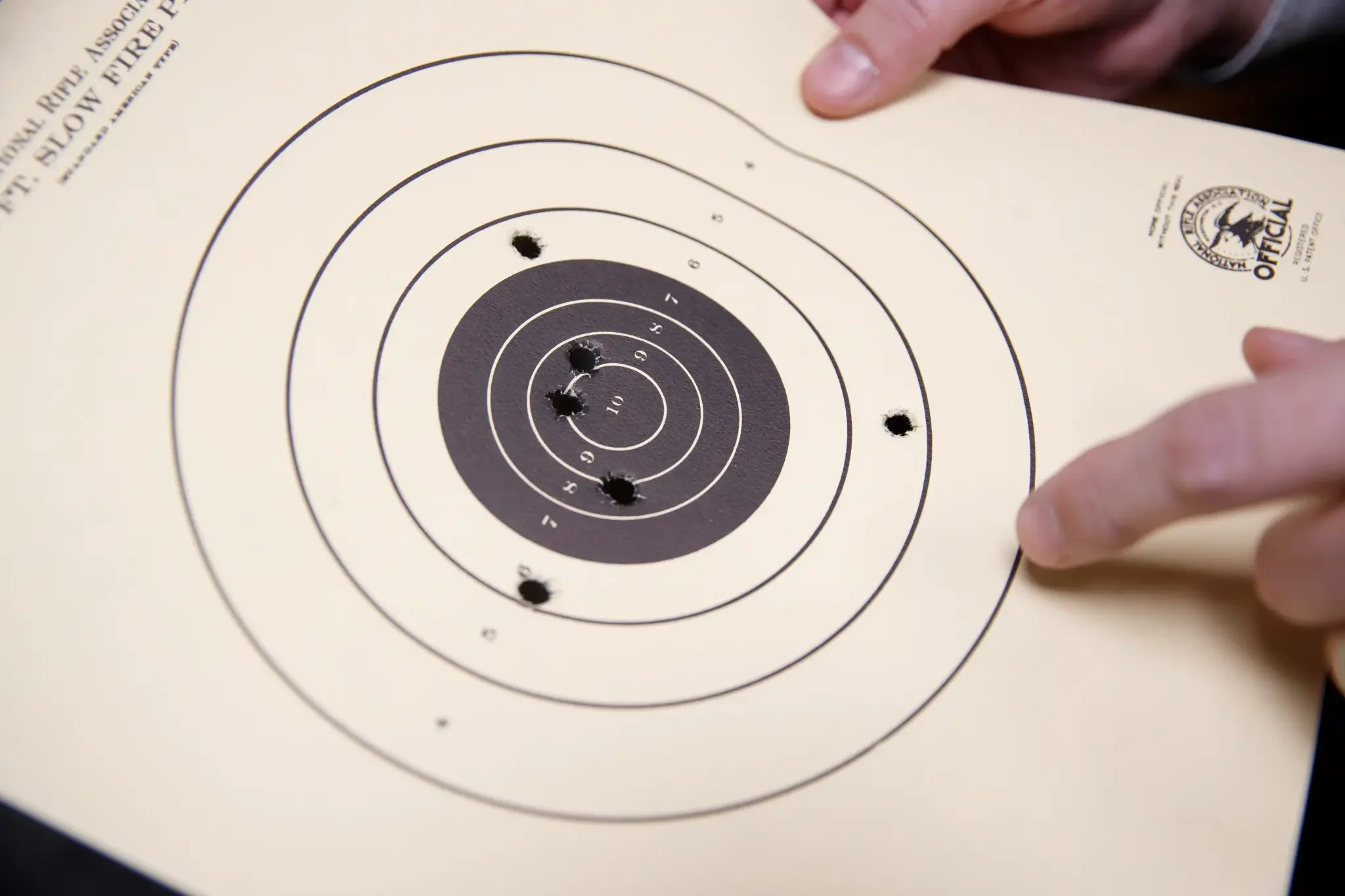

The author finished his weekend course with a paper test — and has gotten better since.Tamara Beckwith/NY Post

Each month, Westside offers sessions compacted into a single intensive weekend course. The spaces fill, so sign up early. Two dozen of us met in the cluttered Westside classroom. We sat on broken-down school desks with patriotic flags lining the walls.

The diversity of students there was a reflection of town. I sat next to the son of a police officer. Behind me was a young woman in a designer coat. Next to her, a man was speaking English as a second language. Some were longtime gun owners upgrading from premise permits. Others had never touched a firearm until the day we gathered.

Our instructor was Glenn Herman, a wry, wiry native of Greenwich Village dressed head to toe in black (his website is appropriately titled newyorkcityguns.com). As he sprinkled in stories of his bar mitzvah, over two days we learned about the history of rifling, the relative advantages between revolvers and semi-automatics, the uses of hollow-point rounds versus full metal jacket, different holster options, sight pictures, misfires, hangfires, squib loads, the isosceles over the Weaver stance and the fundamentals of firearm safety (always point it in a safe direction, always assume it is loaded and always keep your finger off the trigger until ready to fire).

Herman ended the first day by showing us the Glock he keeps in his black fanny pack. “I’m getting older and don’t care what I look like,” he explained.

A diverse group of New Yorkers take aim at the Westside range in the heart of Manhattan.Tamara Beckwith/NY Post

For day two, things got heavier, as we reviewed the true challenges of New York’s gun laws and the legal implications of concealed carry. In response to Bruen, the Legislature imposed a host of new restrictions under its so-called sensitive-place law. These regulations state that you cannot bring a licensed firearm, loaded or unloaded, through much of town, including parks, public transport, restaurants and the “Times Square Exclusion Zone.” Haven’t you seen the signs?

Such restrictions will almost certainly be challenged on constitutional grounds, as they effectively nullify the protections of Bruen. Nevertheless, until then, law-abiding New Yorkers must remain cognizant of the many new impositions. Of course, we should not assume the same cognizance of New York’s criminal class.

Tamara Beckwith/NY Post

Before we finished the weekend course with a paper test and a live-fire drill with a 9-millimeter semi-automatic, Herman went over the ethical challenges that come with concealed carry.

“The city will be different for you when you have a loaded firearm,” he explained. “You must train your mind first to be nonviolent. Cultivate a mindset where your instincts are good and deadly force is used only after all other options have been exhausted, where you have nowhere left to escape, and life is on the line.”

Herman guided us to further study with such gun gurus as Massad Ayoob. His online tutorials on the many nuances of firearms literacy, from grip and stance to legal implications and how to talk to law enforcement, are all must-see.

Tamara Beckwith/NY Post

With the testing done and paperwork submitted, I received my appointment for police fingerprinting.

A few months later, my temporary approval came in, which meant I could finalize the process of getting my dad’s revolver on my license.

In many states, you can simply walk into a gun shop and walk out with a pistol. You can also inherit a firearm like anything else.

Not so in New York. Each firearm must pass through a dealer and be registered to your license before it can be released.

You can also only register one firearm every 90 days. Again, Westside shepherded this process along for me and held onto my pistol until it was cleared.

Tamara Beckwith/NY Post

But I got it, and my concealed-carry license arrived in the mail.

The approval meant I could join the Westside range and shoot whenever I liked.

The old basement range, which has changed little since a scene from “Taxi Driver” was filmed there half a century ago, welcomes all with its donuts and coffee and bonhomie.

I am no great marksman, but I can see incremental improvements in my weekly practice.

Lining up a gun with a target is easy. Keeping it on target as you pull the trigger and handle its recoil, and doing this consistently, is the challenge.

I think of my father firing that same gun. The smell of the gunpowder takes me back to those teenage years with him on the range.

The author poses with his father, Carl Panero, on Gramercy Park after his daughter’s baby naming at the National Arts Club in 2010. Courtesy of James Panero

Still, I wouldn’t mind trying out a smaller pistol.

My Magnum is too large and heavy for pocket carry.

A smaller five-shooter might be in order. Or maybe I should go for a Colt 1911.

Most shooters have moved away from wheel guns altogether in favor of plastic semi-automatic 9-millimeters, such as the Glock.

In any case, it’s nice to have options on your holiday wish list. I’m sure Jabotinsky would agree.