THE NEW CRITERION, December 2022

On the politicization of the American library.

Adapted for The Wall Street Journal of November 11, 2022

In 2006 the American Library Association issued a button to its members. It read, “radical, militant librarian.” We should have taken the message at its word. The American library, until recently a refuge of neutral quietude, has become a booming battleground in the culture wars.

In 2018 the ALA dropped the name of Laura Ingalls Wilder from its annual children’s literature award. The reason? The supposed “culturally insensitive portrayals” in her landmark Little House on the Prairie series. Three years later, the organization published its “Resolution to Condemn White Supremacy and Fascism as Antithetical to Library Work.” The edict claimed that “libraries have upheld and encouraged white supremacy both actively through discriminatory practices and passively through a misplaced emphasis on neutrality.” The proclamation charged the ALA’s “Working Group on Intellectual Freedom and Social Justice” to “review neutrality rhetoric and identify alternatives.”

The quiet, neutral library was out. Full-throated progressive politics were in. As Emily Drabinski, a self-described “Marxist lesbian” who was recently elected president of the ALA, stated on her campaign website: “So many of us find ourselves at the ends of our worlds. The consequences of decades of unchecked climate change, class war, white supremacy, and imperialism have led us here.”

The condemnation of the history of the American library, by its own gatekeepers, has done more than bring “Drag Queen Story Hour” to every children’s reading room. It has also upended the traditional role of the library as an organization primarily dedicated to the acquisition, preservation, and circulation of books. This is a radical overhaul, and it has been brought to us by some of America’s largest cultural philanthropies.

In October the Mellon Foundation hosted a panel discussion on the American library featuring Mellon president Elizabeth Alexander, the ALA executive director Tracie D. Hall, and the Los Angeles City Librarian John F. Szabo. “Library workers are on the front lines of some of our most pressing social justice issues,” began the discussion. They are “no longer relegated to the reference desk.” What does this all mean? For one, that today’s librarians mock “the shushing part” of the traditional library: “I can’t think of too many contemporary library spaces I’ve been in where the librarian is going to be a shusher,” said Hall. “I probably was the librarian that others might have wanted to shush.” Through sewing classes, coworking spaces, and “incubators,” the panel spoke of “fulfilling the promise of what libraries were meant to be in terms of equity.” “It is our responsibility to ensure that no one is left out of the voting process,” Hall added. “That is one of our core values at the American Library Association.” And by actively appealing to voters on one side of the political spectrum, the library organization helps move election outcomes in a desired direction.

As librarians now champion controversial books such as the graphic novel Flamer, they also call parental attempts to limit what children read as evidence of a “period of unprecedented book banning and censorship”—one that “far eclipses even the McCarthy era.” Meanwhile, truly deplatformed titles, such as When Harry Became Sally, Ryan T. Anderson’s critique of modern transgender theory that Amazon erased from its e-commerce platform, are never mentioned in these one-sided agonies. “This is the third great wave of librarianship and libraries—as a social project,” concluded Hall. What was, until recently, a widely popular American institution has been nearly broken by unrestrained progressive politicization.

“I suspect that the human species—the only species—teeters at the verge of extinction, yet that the Library—enlightened, solitary, infinite, perfectly unmoving, armed with precious volumes, pointless, incorruptible, and secret—will endure.” It is easy to see how Jorge Luis Borges in the early 1940s, in his oft-quoted short story “The Library of Babel,” might have drawn such a conclusion. Yet today it appears that the library, especially the library that is “enlightened, solitary, infinite, perfectly unmoving, armed with precious volumes, pointless, incorruptible, and secret,” is the entity that most teeters at the verge of extinction.

It is a crisis of the Left’s own devising, one designed to turn the library into a scarred landscape. It is also based on a straw-man argument, with rhetoric disconnected from the historical record. Far from upholding “fascism” and “white supremacy,” the American library has been, in fact, one of the country’s most enlightened and democratic institutions.

Through what remains of this legacy, beyond the spurious “banned books” displays and the circulation-desk sermonizing, today’s libraries can still be places of reverie, uplift, and reflection. This effect is due not just to the abundance of books that are—at least for now—still available for perusal. It is also an effect of the library building itself, its history of form, which records the values of an earlier era in bricks and stone.

For its ubiquity and richness, especially in those examples that survive from before the Second World War, the American library building stands as a reflection of the country’s enlightened calling. Over the nineteenth century and into the early decades of the twentieth, library design paired historicized style with the latest innovative solutions for the safe housing and circulation of its collections. The references to the history of art and civilization that these buildings displayed on their faces—and the great expense dedicated to their creation and upkeep by their underwriters—reflected a reverence for the culture of the book contained within.

Henri Labrouste, Bibliothèque Ste.-Geneviéve, Paris, 1859, Print, from Memoirs of Libraries, London.

American Libraries: 1730–1950, written by Kenneth Breisch for a series by the Library of Congress and published in 2017, tells this history in a visual and compelling way.1 While the eighteenth century saw the creation of important American private and subscription libraries, only Benjamin Franklin’s Library Company of Philadelphia (founded in 1731) and the New York Society Library (founded in 1754) had buildings dedicated to their collections by the turn of the nineteenth century. America’s interest in library design began in earnest after 1800. Over the following century and into the early years of the twentieth, libraries took the country by storm. Planners found inspiration in the grand mid-nineteenth-century examples of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris (designed by Henri Labrouste and constructed between 1844–50) and the Reading Room of the British Museum in London (Sydney Smirke, 1854–57). American library construction took off after the Civil War to reach the pinnacle of the movement as seen in such edifices as the main branch of the Boston Public Library (McKim, Mead & White, 1895), the main branch of the New York Public Library (Carrère & Hastings, 1911), and Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library (James Gamble Rogers, 1931).

Unlike the museum, the library is an ancient form. The Ambrosian Library in Milan (Lelio Buzzi and Francesco Maria Richini, 1603–09) and the Bodleian Library at Oxford (Thomas Holt, 1610–13) provided the “hall model” for early American library construction, one that lined the high walls of the main rooms with books. Centuries later, private showcase collections such as New York’s J. Pierpont Morgan Library (McKim, Mead & White, 1902–06), Rhode Island’s John Carter Brown Library (Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, 1904), California’s Huntington Library (Myron Hunt, 1920), and Washington’s Folger Shakespeare Library (Paul P. Cret and Alexander B. Trowbridge, 1928–32) continued the tradition of the Renaissance treasure-house design.

As a modification of the hall design, the alcove model, with double-height C-shaped book walls, became the American standard by the mid-nineteenth century. At Harvard, Gore Hall (Richard Bond, 1837–41; demolished in 1913 for the construction of Widener Library) became the university’s first freestanding library and a standard of alcove design. The form was continued in Yale’s Dwight Hall (Henry Austin, 1842–47; converted into the Dwight Memorial Chapel in 1930–31) and the successive buildings of the New York Society Library of 1840 and 1856. Merging the literary and ecclesiastical, both Gore and Dwight Halls drew their inspiration from King’s College Chapel in Cambridge, England.

Two influential manuals of the 1840s—A. F. Schmidt’s Handbuch der Bibliothekswissenschaft (1840) and Léopold Auguste Constantin Hesse’s Bibliothéconomie (1841)—encouraged multistory alcove design. Yet it was the widely emulated work of Henry Hobson Richardson, a onetime Harvard undergraduate who had studied in Gore Hall, that assured the alcove’s popularity, thanks to his library designs for the Massachusetts towns of Woburn, North Easton, Quincy, and Malden (1876–85). With its monumental ashlar masonry supporting fanciful arches and turrets, the Richardsonian Romanesque-revival style can still be seen in libraries throughout New England.

Not everyone was a supporter of Richardson’s alcove system—in particular those librarians who worked with collections housed in these arrangements. Justin Winsor, the superintendent of the Boston Public Library from 1868 to 1877, and William Frederick Poole, the librarian of the Boston Athenaeum from 1856 to 1869, were both critical of multi-story book halls and alcove shelving for their inefficient use of space, the challenge of retrieving the volumes, and the uneven heating of the rooms, which would often cook the books on the higher shelves. Their solution was the more utilitarian stack system, which located books in dedicated spaces on multiple tiers of iron shelves. The British Museum Reading Room employed, in part, such a multi-tiered system.

As American universities began to emulate the research-based German model, library collections grew. A more modular and efficient stack system soon became a necessity. Gore Hall was built in 1841 to house forty-four thousand books—the extent of Harvard’s collection at the time. The building was filled by 1863 and supplemented by a stack annex, the first in America, in 1876. Nevertheless, by 1910 an architectural survey determined that “no amount of tinkering can make it really good.” As with other alcove libraries, Gore was said to be “hopelessly overcrowded” and “intolerably hot in summer.” In 1913 Harvard demolished Gore and replaced the influential nineteenth-century complex with Horace Trumbauer’s Harry E. Widener Memorial Library, with metal stacks capable of storing over 3.5 million volumes. What was lost in bibliographic visualization—with the architectural use of books now replaced by card catalogues—such stack libraries gained in essential storage and efficiency. By the time of the construction of Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library, its Gothic Revival façade concealed a fourteen-story stack tower capable of housing five million volumes.

Thomas Jefferson was a man ahead of his time—in library- as well as nation-building. His legacy is woven into the story of the American library in more ways than one. By the early years of the republic, Jefferson had amassed a personal collection of six to seven thousand volumes. It was the largest and most extensive library in the country at the time. After the British army sacked Washington, D.C., and burned the Capitol in 1814, destroying the congressional library housed within, Jefferson sold his collection to the federal government a year later. Even though a second fire destroyed two-thirds of these volumes in 1851, Jefferson’s collection continues to form the nucleus of the Library of Congress, which has grown to become the largest library collection in the world.

Jefferson Reading Room, Library of Congress. Photo: Carol Highsmith, 2009.

Jefferson’s library influence continued with his designs for his University of Virginia. In 1822, construction began on his Rotunda library. The design departed from the hall model and adopted the shape of the ancient Roman Pantheon to form a focal point for his university’s classically designed Academical Village. When completed in 1828, two years after Jefferson’s death on July 4, 1826, and as the final and most monumental building on the new campus, the two-story Rotunda became the first freestanding academic library in the country.

Half a century later, library designers returned to Jefferson’s classical vernacular and the rotunda form to create some of the greatest monuments of American library architecture. Again Sydney Smirke’s innovative British Museum Reading Room of 1856 provided the model for a domed central rotunda featuring a panoptic administration area at the center with freestanding bookstacks surrounding a core. Smirke’s innovative reading room, the first to use iron stacks, featured twenty-five miles of reference shelving with twenty thousand popular circulating volumes arranged in numbered alcoves a floor below.

When the U.S. government authorized a competition for a new Library of Congress building in 1873, the winning design coalesced around a similar rotunda-and-stack arrangement. Completed twenty-five years later in 1897, what is now known as the loc’s Thomas Jefferson Building spared no expense in its construction and decorative program. Edward Casey, the son of Thomas Lincoln Casey, the engineer who oversaw the library’s construction before his death in 1896, attended to the library’s lavish assembly of sculptures, murals, and mosaics. Illustrations on its walls depict the evolution of the book from the oral tradition through the invention of the printing press. The collar of its central dome features allegories of the world’s civilizations. Surrounding this program are forty-three miles of shelving manufactured by the Snead & Company Iron Works of Louisville, Kentucky, which can accommodate two million volumes.

The Library of Congress’s rich artistic program was arguably surpassed at the Boston Public Library, where Charles McKim tasked Puvis de Chavannes with producing a mural cycle for the library’s grand staircase. Puvis created the work relying on measurements sent by McKim and a sample of the yellow Siena marble to match the tonalities of the staircase enclosure. Using a scale model of the staircase and working on canvas in his French studio, the seventy-two-year-old artist created a cycle of paintings that were then shipped to Boston and adhered by his assistants to the walls. The long cycle atop the entrance to Bates Hall presents “The Muses of Inspiration Hail[ing] the Spirit, the Harbinger of Light.” Surrounding panels depict allegories of Philosophy, Astronomy, History, Chemistry, Physics, and Pastoral, Dramatic, and Epic Poetry. Below, carved lions by Louis Saint-Gaudens guard this grand staircase.

In the years after the completion of the loc’s Jefferson building, American architects revisited the rotunda model in even more impressive distillations of the classical style as taught by the École des Beaux-Arts. In the first decade of the twentieth century, two institutions—New York University and Columbia—developed new uptown campuses that had many parallels. Most notable were the domed rotunda libraries at their core: nyu’s Gould Memorial Library of 1896–1903 and Columbia’s Low Memorial Library of 1909. Both designed by the firm of McKim, Mead & White, each building carries the sensibility of one side of the partnership, with McKim’s restrained, detailed classicism on display at Low and White’s theatrical exuberance at Gould.

Beyond the triumphant designs of America’s turn-of-the-century central libraries, it was the development of the smaller branch library that arguably had the greatest effect on twentieth-century literacy and education. As early as 1885, William Frederick Poole was advocating for smaller circulating libraries, ones that might contain thirty thousand volumes and be easily accessible to the American reader. A supporter of libraries of all sizes, the philanthropist Andrew Carnegie answered this call in the early years of the twentieth century in ways that changed the landscape of the American library. By 1917, Carnegie and his foundation, which he started in 1911, had endowed 1,679 library buildings in the United States. In New York City alone, he spent $5.2 million to construct sixty-seven neighborhood branch libraries. In segregated Tennessee, he funded a Negro Branch library. At the request of Booker T. Washington, he donated $20,000 for the library at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute. The ubiquitous construction of these Carnegie libraries, mostly classical in style, called for a simple panoptic design where “one librarian can oversee the entire library from a central point,” in the words of James Bertram, Carnegie’s personal secretary.

Through an astonishing combination of municipal underwriting and philanthropic giving (New Hampshire became the first state to authorize taxation for libraries in 1849), today there are 5,400 libraries with a thousand or more books in the United States. What has been lost in this abundance is an understanding of the forces that created it and an appreciation for the styles that formed it. Following the Second World War, library designers turned away from historical models to look to the modern office building and department store for inspiration, with disastrous effects. The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale (Gordon Bunshaft, 1963) and the Phillips Exeter Academy Library (Louis Kahn, 1972) are the rare exceptions to this general rule.

Departing from the simple flagstone design of Franklin Roosevelt’s “presidential library” (Louis Simon, 1939–40)—the first such executive initiative—the libraries of Lyndon Johnson (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, 1967–71) and Bill Clinton (Polshek Partnership, 2000–04) are brutalist and impenetrable. The same goes for the James Madison Memorial Building (De Witt, Poor & Shelton, 1966–81), the much-criticized extension of the Library of Congress built at a cost of $131 million, where the first challenge is finding the monolith’s front door. Even after the government requested a review of the design by the American Institute of Architects in 1967, little changed in its final construction.

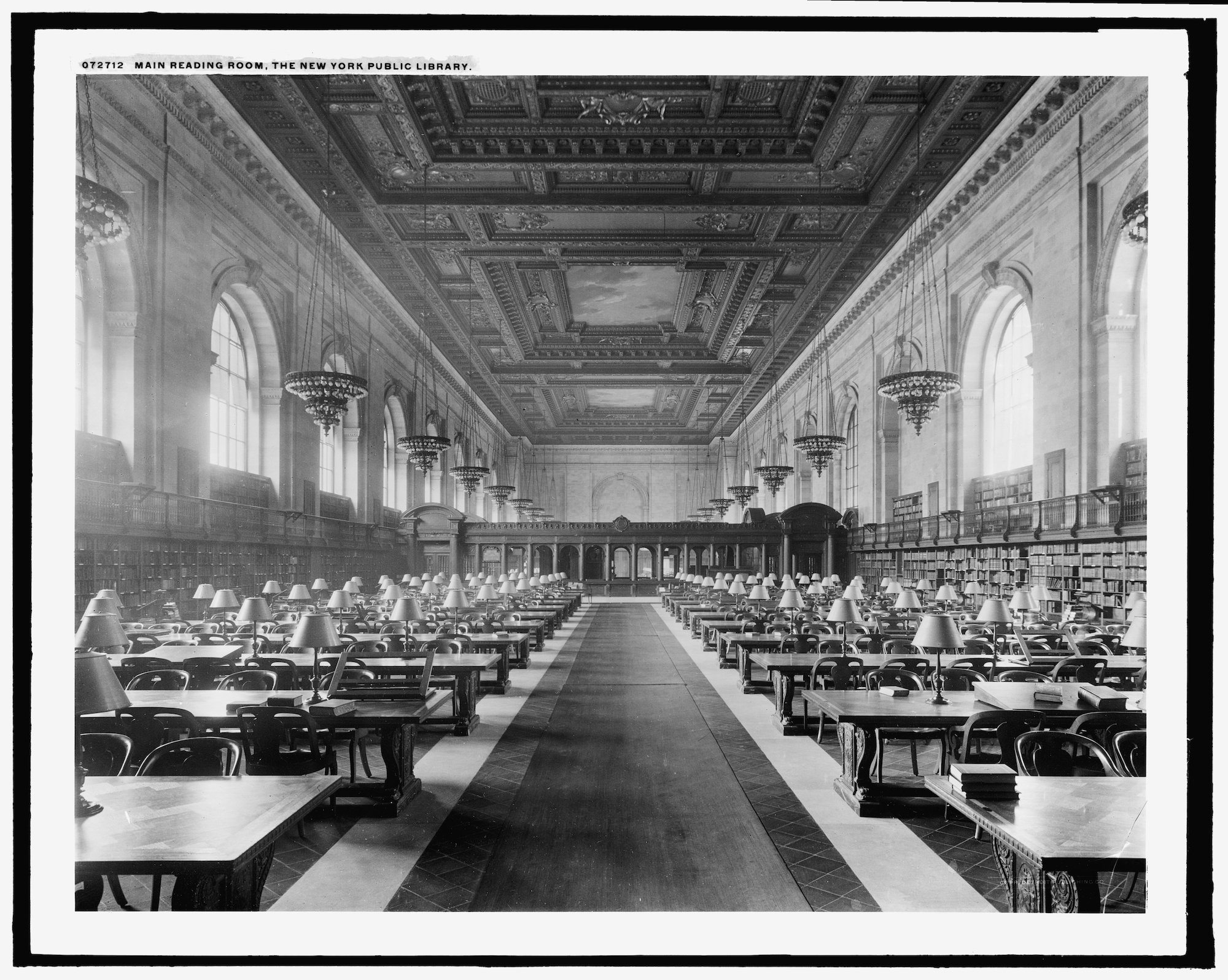

Detroit Publishing Company, Main reading room, the New York Public Library, ca. 1910, Dry plate negative, Library of Congress.

Now a radical “third great wave” seeks to wash over the American library to complete its transformation into a “social project.” A decade ago, the leadership of the New York Public Library unveiled a real estate consolidation scheme called the “Central Library Plan.” The aim was to transform the library’s flagship research branch—arguably the finest integration of public spaces and book storage in the country—by gutting its stacks. By removing the “seven floors of outdated bookshelves under the Rose Main Reading Room,” read the announcement, the plan promised to transform the reference library into a newly circulating “people’s palace.” Meanwhile millions of books from the library’s “core research collections” would be moved off-site—undermining the legacy of John Jacob Astor, who left the initial bequest of $400,000 for the foundation and support of a free public reference library in 1848.

An eleventh-hour appeal by the architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable and others tanked the scheme, but the episode reveals the lengths to which library leaders will now go to destroy America’s great history of literary access for progressive ends. For them the real problem is not “book banning” but the easy availability of books they despise and the history these books represent, which our great library collections offer up neutrally, and impartially, by design. A library of the book, by the book, and for the book is the ultimate defense against their control—and the true democratic legacy of this American institution.

American Libraries: 1730–1950, by Kenneth Breisch; W. W. Norton & Company, 320 pages, $75.