THE NEW CRITERION, September 2024

On the life & work of Joe Zucker.

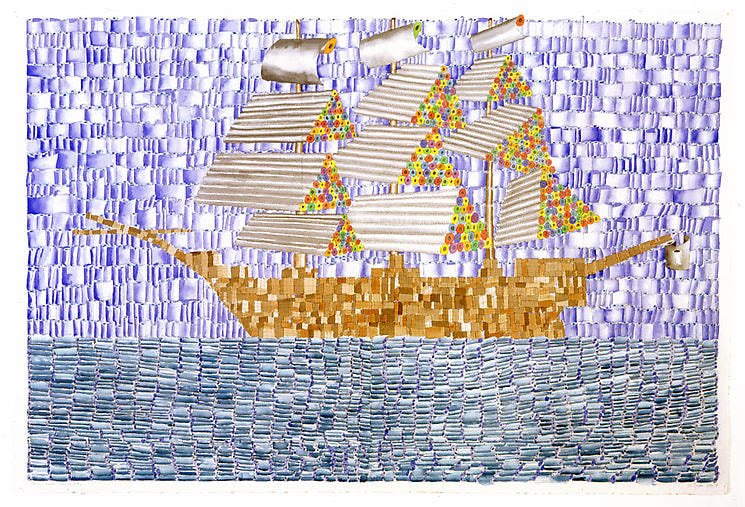

The art world never knew what to make of Joe Zucker, a painter who died in May at the age of eighty-two. Just as pirates became a recurring theme in his work, Zucker took a piratical stance on art history. He refashioned the flotsam and jetsam of pictorial space to raise his own Jolly Roger over the scurvy dogs of modernism in a way that fit nobody’s story of art but his own.

Like Augie March, Zucker was “an American, Chicago born.” Growing up Jewish on the city’s South Side, he spent his childhood at the museum of the Art Institute. His father was a scrap-metal dealer. His mother, a nurse, deposited him at the museum starting at an early age to avoid the ethnic warfare of the streets. Here he absorbed an aesthetic education that was democratic and particularly American, one that flattened chronology and place—a “Veronese one day, a de Kooning the next, Van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles,” he said. Back home, through an affinity for literature and narrative, he further mixed high and low—Willa Cather with Studs Terkel, Herman Melville with N. C. Wyeth’s illustrations for Treasure Island.

Chuck Close, Joe Zucker, 1969, Gelatin silver print, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City.

After a stint at Miami University of Ohio, where he played basketball, Zucker returned to Chicago. He enrolled at the School of the Art Institute, earning his undergraduate and graduate degrees. He joked that here he learned to draw a skeleton riding a bicycle from memory. As with much of Zucker’s artistic identity, this was fact and fiction mixed in a medium of dry wit. The tall tale reflects the degree of technical training he received without any particular sense for what to do with it, especially since he said he never wanted to be the next jock from the School of Paris flexing a Picasso brush. “My real love is being an artist and making art,” he once said. “Not advancing the myth of modernism.”

As he stared at his canvas, an early moment of doubt became Zucker’s first artistic breakthrough. Uncertain what to paint, he set about depicting the painting itself—in particular, the warp and weft of the canvas’s weave. His subsequent abstractions of interwoven rectangles brought to mind the rigors of Piet Mondrian but also the basket weaves of brightly colored plastic lawn chairs, which were then a ubiquitous feature of demotic Americana. Zucker’s interest in vernacular, in the elevation of craft and domesticity against the backdrop of high art, in grids and recursive rules, and in the conflation of process and product, were already apparent and continued throughout his career. His circular logic could be confounding, but Zucker flavored such Möbius strips like salt-water taffy—palatable, mysterious, and (as his last name might suggest) sweet.

After teaching at the Minneapolis School of Art, Zucker moved to New York in 1968. He soon fell in with Klaus Kertess and the iconoclastic artists he was showing at his Bykert Gallery, who included Lynda Benglis, Dorothea Rockburne, Barry Le Va, and Brice Marden. Among them was Chuck Close, who became Zucker’s loft neighbor on Prince Street and drinking buddy as they taught together at the School of Visual Arts. In one of his early portraits, Close depicted Zucker in horn-rimmed glasses and shirt and tie, with his hair slicked back in a way that resembled an overtaxed insurance salesman. A study for this work is now in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Joe Zucker, Amy Hewes, 1976, Acrylic, cotton & rhoplex on canvas, Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

“Joe Zucker has consistently for over four decades been one of America’s most innovative artists,” Close wrote for Bomb magazine in 2007.

His paintings are personal, quirky, idiosyncratic, and often puzzling. His style is rooted in processes, some simple, others remarkably complex. . . . Pouring, squeezing and manipulating paint, he fashions paintings so personal it would be impossible to imagine anyone else having made them. This is the definition of personal invention.

Close went on to say of Zucker that there was “no greater influence on the way I think about painting, and no person who played a more important role in the formative period of my work and changed my mind about how paintings can and should be made.”

A decade later, when I assembled an exhibition of Zucker’s depictions of the sea for the National Arts Club, Close wheeled into the opening. As I plied him with martinis, he explained how he and Zucker together learned to develop processes to complicate and “de-skill” their means of representation. “This is something you and I have spent a lot of time doing, removing the taboo of talent,” Zucker said in response to Close in that 2007 interview. Here was a problem, I concluded, only for those specimens for whom pictorial talent comes too easily.

As might any artist who chooses to start his career by painting the materials of a painting, Zucker next set about working up an index for his oeuvre-to-be. The 100-Foot-Long Piece (1968–69) is the first work he made in New York. In the 2020 monograph on Zucker published by Thames & Hudson, Terry R. Myers wrote how the work was “like a catalogue of available merchandise (as he called it, ‘the Sears catalogue’),” one that “retains many of the material characteristics of life in the suburban Midwest.” Made up of rectangular strips in a range of styles, some abstract, others representational, created through a wide array of processes, the mixed-media work can resemble a row of linoleum patterns or wallpaper swatches. Faux fabrics are intermixed with a depiction of Billy the Kid. An illustration of the Charioteer of Delphi is featured alongside cones of mathematical plotting-paper sticking out from the picture plane. “One area was wood-burned,” Close approvingly remarked. “When was the last time you saw a work of art by a serious artist that was made with a wood-burning kit?” A young secretary at Kertess’s gallery dubbed the work “tossed salad.” That secretary, Mary Boone, went on to become a mega-gallerist of the 1980s and even represented Zucker for a period in the 2000s. “It was as if all my styles I made at once, rather than the more usual linear development of style,” Zucker remarked. “I made enough styles to last a lifetime.”

Joe Zucker, Paying Off Old Debts, 1975, Acrylic, cotton & rhoplex on canvas, Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

Writing an introductory essay for the 2020 monograph, John Elderfield noted that Zucker may have developed up to eighty different series through his career: “Having many sides is integral to his self-presentation as artist.” The 100-Foot-Long Piece featured a preview of the one that became his most consequential: his cotton-ball paintings. Zucker developed these works using Rhoplex, an acrylic binder developed in the 1950s by the Rohm and Haas chemical company for use in cement and spackle with an “exceptional pigment-binding capacity.” By dipping cotton balls in Rhoplex, which he then hand-tinted and adhered to canvas, Zucker devised a method of painting that resembled a pixelated screen, one that could convey a recognizable image.

At first Zucker used this labor-intensive process to draw a connection to Byzantine mosaics. Woman with Halo and Scepter (from Five Mosaics) (1972), which referenced the art of Ravenna, is now in the collection of the Art Institute. Five Amphoras (1972) is at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. From a distance, the works read as recognizable images. Up close, the brightly colored cotton balls resemble piles of tufted carpet. “It took months to roll up the pieces of paint,” Zucker said of his process, “and then all of the paintings were finished in a minute.”

Zucker then looked to the history of cotton and the role of labor in its cultivation and trade. Drawing on photographs of riverboat freight from the American South, Zucker loaded his imagery with historical import at a time when few contemporary artists dared look beyond the clean surfaces of minimalism or the safety of pop aesthetics. Rendered in grisaille, reflecting old photographic source material, subjects such as the riverboat in Amy Hewes (1976), in the collection of the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College, and the laborer in Paying Off Old Debts (1975), in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, convey a haunting presence, as if the history of American slavery were reaching out through the very cotton of the works.

By the time I first came across Zucker’s work, some twenty years ago, he had long since moved to East Hampton, Long Island, where he established a home and studio in the 1980s with his wife, Britta Le Va. Here he coached high-school basketball as a volunteer for the championship Bridgehampton team with players far removed from the area’s multimillion-dollar summer residences. (His efforts were featured in the 2017 documentary Killer Bees, produced by Shaquille O’Neal, about the team as it defended its state title.)

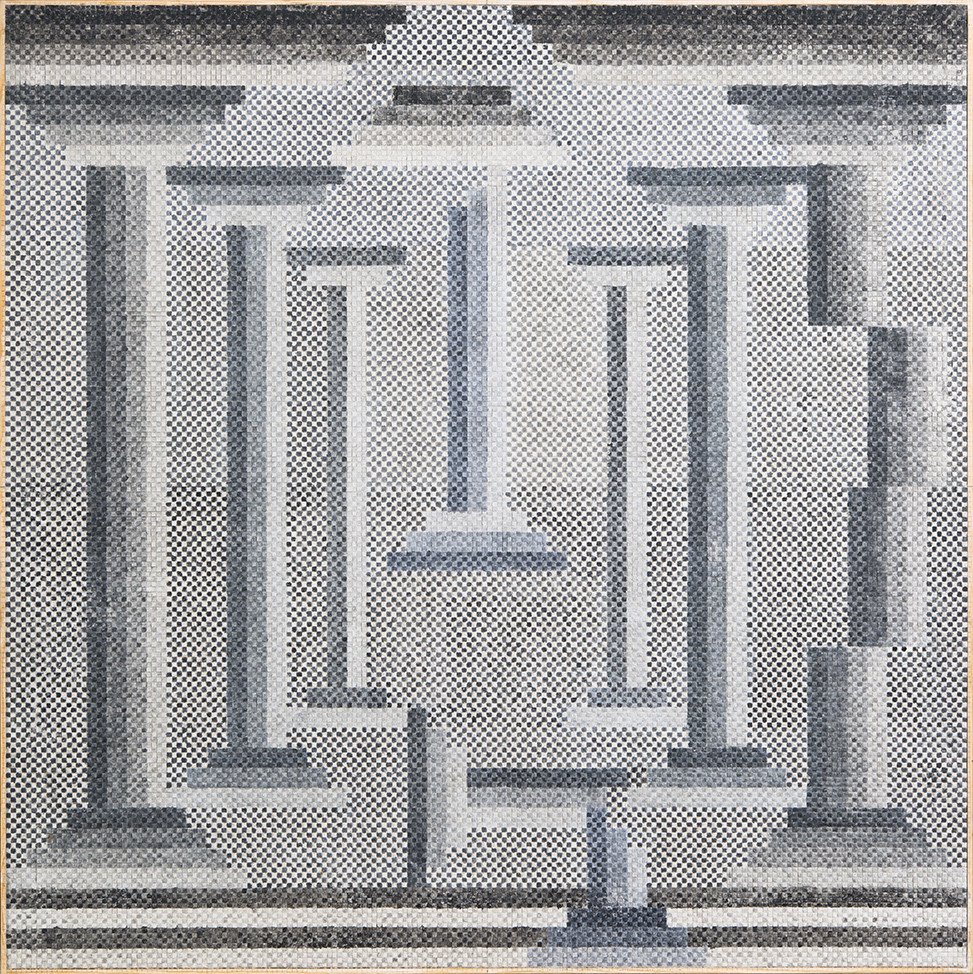

Joe Zucker, Russian Empire, 2012, Watercolor & gypsum on plywood, Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

Zucker was ahead of his time in his use of unorthodox materials and techniques, not to mention his resurfacing of fraught historical subject matter. Yet the Neo-Expressionists and the “Pictures Generation” of the 1970s and 1980s had little use for his involved and at times confusing work. Nevertheless he continued to develop new series, drawing on everything from pegboards and squeegees to the history of Joseph Smith, sometimes combining all three.

The work centered on shipping, marine life, and piracy could be his most satisfying. A 2008 exhibition at Nyehaus Gallery called “Plunder,” which featured rolls of canvas cut through with cannonballs, was particularly successful. For Zucker, the map was the territory. Allegory and allusion mixed with the concrete. “The ghostly spectre of the slaver Trinidad rises among the wrecks and reefs of Madagascar on a moonlit night during July of 1834,” he scrawled across a drawing from 1978, which I first saw at

Nolan/Eckman Gallery. On a diagrammatic image called Axe Lake (Legend) (1994), Zucker included a key that listed the fishing spots and mills along with his vodka martinis and gibsons.

Water served as a recurring theme in Zucker’s churned processes. He saw a connection between the surface of the painting and the “machinery depicted in the painting—objects that stir water, such as planes, windmills, ships, wheels.” It helped that Zucker was himself an accomplished fisherman—skills he developed through weeks-long expeditions to Minnesota and as the captain of a fishing boat he docked in Montauk harbor called The Rodfather. Following a few occasions when I paid studio visits to East Hampton, we motored out to the reefs off Montauk. Zucker knew just the right time and place to put down line for striped bass as he named the fish he caught. “Nancy Pelosi” was his keeper. I called mine “Mahmoud A. Bass.”

In East Hampton, Zucker developed several series that hearkened back to the warp-and-weft grids. I am unsure if one series involving mops dipped in paint, arranged on the wall as if woven together, has ever been fully executed. Another series, of gypsum board hand-scored and water-colored into tight grids resembling tesserae, recalled those earlier Rhoplex mosaics. He titled the 2013 exhibition of this series at Mary Boone “Empire Descending a Staircase.”

Joe Zucker, Robocrate Flagship #2 (1955–1960), 2004, Watercolor, ink & graphite on paper, David Nolan Gallery, New York.

Zucker’s final series was inspired by stories of the Pale of Settlement by Sholem Aleichem, which he read during the 2020 covid shutdowns. Made of cast-off studio trash, such as cardboard, towels, and rubber mats, the austere monochrome paintings of shtetl houses and abstracted snowmen, depicted in a chilling, white landscape, felt like a fresh airing of sublimated forces and materials. In the summer of 2022, I paid my final studio visit to see this work. Zucker by then had already suffered a series of health setbacks, including the consequences of a traffic accident and metabolic encephalopathy. As I slept on a cot in his spider-filled studio, I could hear Zucker in the other room narrating his own demise.

“There’s a surprise to his work,” the critic and poet John Yau explained as I sat down for an interview with him and Zucker in 2016. “The humor is very generous. If anything he’s self-mocking. He’s mocking the idea of being an artist, but in a kind of generous way.” In much of Zucker’s work, as in my final moments with him, you never know whether to laugh or cry.