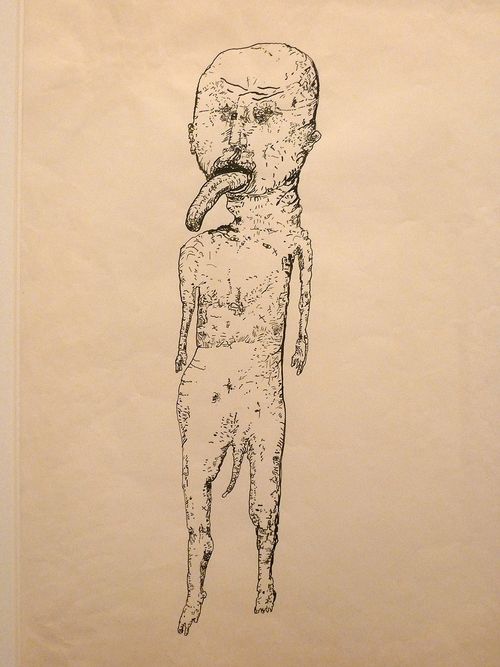

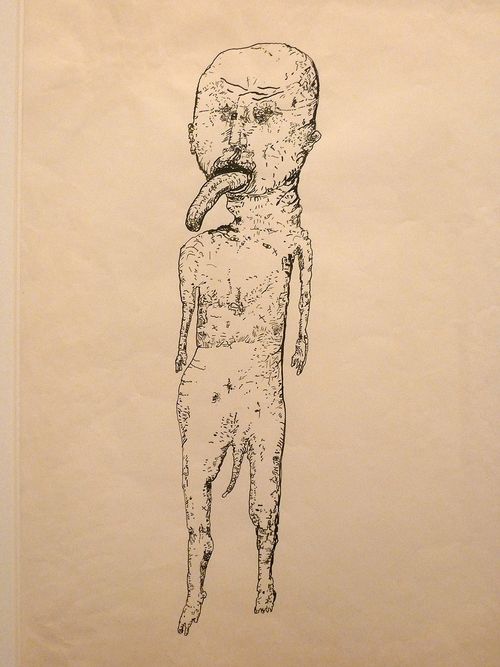

Ohne Titel/Untited by Eugen Schönebeck (pen on paper, 60.9x42.9cm, 1963)

THE NEW CRITERION

October 2012

Gallery Chronicle

by James Panero

On “Line and Plane” at McKenzie Fine Art, “Fred Gutzeit: SigNature” at Sideshow Gallery, “Heroes” at Small Black Door, “Jon Schueler: The Mallaig Years, 1970–75” at David Findlay Jr. Gallery & “Eugen Schönebeck: Paintings and Drawings, 1957–1966” at David Nolan Gallery.

The start of the New York art season can seem like going back to school. The furious few weeks of openings following Labor Day serve as student orientation. Everyone’s on campus, classes begin, and you get a good sense of what the semester will bring.

In the galleries, all early indications suggest this will be a very good year. I found strong inaugural exhibitions across every gallery neighborhood I visited. And for all the ones I saw, there were others I wanted to catch but just couldn’t before press time. These include the early photographs of Ai Weiwei at Carolina Nitsch; Thomas Micchelli’s figure drawings at Centotto; “Land Escape” at Parallel Art Space; Chuck Bowdish’s paintings, drawings, and collages at Steven Harvey; and “To Be a Lady: An Exhibition of Forty-five Women in the Arts,” curated by Jason Andrew at the former UBS Art Gallery in Midtown. There’s more good art to see than could possibly meet the eye.

This solid start is in contrast with what’s happening at New York’s museums. Over dinner, an independent curator explained to me that she would now rather organize an exhibition at a respected gallery than at The New Museum. With its hacked-up walls, its self-dealing, and its parade of second-rate shows, The New Museum has become such a pariah that (as an artist recently confirmed to me) to exhibit there is to blow your shot at a real New York museum show.

But then, what’s become of the real museums? Over a weekend in September, the Brooklyn Museum awoke from its slumber to engage with art made in its own backyard, which it had, up to that point, all but ignored. Yet the museum’s initiative, “Go Brooklyn,” a “community-curated open studio project,” amounted to little more than a social-media marketing gimmick. After suggesting that artists open their studios across Brooklyn, the museum turned them into unpaid contestants competing for studio “check-ins,” where the “ten artists with the most voter nominations will receive visits from Brooklyn Museum curators.” Sure, it was possible to see some great work, but it would have been far better (and truly generous) if the Brooklyn Museum had put its muscle behind each neighborhood’s existing open-studio weekends rather than leverage its own art crawl.

Since the Brooklyn Museum was a partner in the canceled reality-TV show “Work of Art,” the institution may now assume that connoisseurship is little more than a contest. Do I need to suggest that curators shouldn’t need a popular vote to visit studios? Or that artists shouldn’t be the pawns in a museum’s marketing campaign? Until now, the artists of Brooklyn have thrived without the help of the Brooklyn Museum. “Go Brooklyn” suggests the borough was better off without it.

Fortunately, unlike the Brooklyn Museum, we still have the Metropolitan Museum, where scholarship . . . oh wait. Since the retirement of Philippe de Montebello in 2008, we’ve all been wondering whether this institution, under the directorship of Thomas Campbell, would continue to be a stalwart for serious art or fall prey to the temptations of populism that defined Thomas Hoving, de Montebello’s predecessor.

Hoving described his promotion of blockbuster exhibitions—such as his late-1970s circus act from the tomb of King Tut—as “making the mummies dance.” In contrast, de Montebello repeatedly demonstrated that a great exhibition needed little fanfare to attract an audience. Admission statistics alone were no measure of importance, and an inverse relationship appeared to exist between an exhibition’s promotional budget and its artistic merit.

Now following its recent blockbuster costume show for the designer Alexander McQueen, the Metropolitan has again begun touting its turnstile numbers as a sign of success, not to mention a source of revenue. With advertisements plastered across town, events sponsored by the Campbell’s Soup Company, and Hollywood celebrities shilling in its marketing campaign, the Met suddenly seems to be everywhere except where it needs to be—as the example of an institution that takes itself seriously. With “Regarding Warhol, Fifty Years, Sixty Artists,” Tom Campbell’s soupy show might make Hoving dance, but it appears to be little more than a dumbed-down spectacle designed to juke the stats at the ticket counter.

This all goes to show how fortunate we are for the life of art that exists outside museums. Consider this interesting dynamic. The non-profit museums promote themselves; the commercial galleries promote the art. One enriches an administrative class through tax breaks, ticket returns, and government subvention, all while claiming to fulfill an educational mission; the other largely lives off sweat equity, charges no admission, and actually educates the public by displaying a great breadth of art without any guarantee of financial return.

At the galleries, the season began with openings across the Lower East Side. Many of the galleries here are descendants of the smart, smaller venues that once lined the upper floors of buildings in Soho, Chelsea, and the Upper East Side. My tour began with Matthew Miller’s haunting self-portraits at Pocket Utopia (I covered Miller’s paintings at length in my column of June 2011). It continued with Sandi Slone’s pearlescent abstractions at Allegra LaViola Gallery, Drew Shiflett’s paper constructions at Lesley Heller Workspace, and Charles Hinman’s canvas sculptures at Marc Straus.

A standout among many was the group show “Line and Plane.” McKenzie Fine Art is the latest LES arrival, leaving an upstairs venue in Chelsea for a large storefront on Orchard Street. The gallery specializes in geometric abstraction, and these strengths were all on display in a group show with several artists I have praised in these pages, including Don Voisine, Halsey Hathaway, Gary Petersen, Rob de Oude, and Lauren Seiden.

In Williamsburg, Fred Gutzeit has put his signature on “SigNature” at Sideshow Gallery. Through photographs, watercolors, and computer manipulation, Gutzeit transforms street graffiti into op-art abstraction. Atop eye-popping patterns, he signs his paintings in a script of taffy swirls. While the underlying patterns can interfere with the energy of the writing, Yijing sig. 5 has such flourish it calls to mind (to my mind, at least) Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottoman Sultan with one of history’s great tags.

Further out in the outer boroughs, several openings in Ridgewood, Queens had me riding the M train in what was a personal first. This lovely, middle-class neighborhood that borders Bushwick, Brooklyn, features some of the city’s more interesting apartment galleries, such as Valentine, now with a smart group-painting show. The nearby venue Small Black Door is a basement space true to its name. Currently behind its tiny entrance is an excellent survey of local artists. Organized by the painter Julie Torres, one of the neighborhood’s art evangelists, “Heroes” brings together twenty-four artists who have in some way contributed to the community beyond their own work.

Several here have organized their own gallery spaces and art events (Liz Atzberger, John Avelluto, Deborah Brown, Kevin Curran, Joy Curtis, Paul D’Agostino, Rob de Oude, Lacey Fekishazy, Enrico Gomez, Chris Harding, Lars Kremer, Ellen Letcher, Amy Lincoln, Matthew Mahler, Mike Olin, James Prez, Kevin Regan, Jonathan Terranova, and Austin Thomas). Others have been writing about them for blogs and newspapers (Brett Baker, Paul Behnke, Sharon Butler, Katarina Hybenova, and Loren Munk). With work that can be as engaging as their advocacy, all of these “heroes” speak to the vitality of art on the periphery.

In midtown, David Findlay Jr. Gallery presented “Jon Schueler: The Mallaig Years.” Visiting the Sound of Sleat off the western coast of Scotland, Schueler (1916–1992) captured the energy of the sky in Wagnerian tones. A B-17 navigator based in England during World War II, Schueler spent his war years inside a plexiglas nose cone “as though suspended in the sky,” he later said. His paintings are infused with “red thoughts” and the “red of rage,” with glowing clouds parting on an unknown skyscape. With thin coats of pigment, Schueler combined the lessons of his teacher Clyfford Still with the fury of Turner. He took on Ab-Ex scale to produce work that occupies a middle ground between Mark Rothko and Milton Avery—part abstract, part representational, and fully ominous.

Among several strong shows in Chelsea, including Carolanna Parlato at Elizabeth Harris and Katherine Taylor at Skoto Gallery, David Nolan has mounted one of the best of them, with an historical exhibition of the greatest post-war German artist you’ve never heard of.

Coming from the Communist East, moving to the West, and struggling to find a voice outside of Cold War ideology, Eugen Schönebeck in many ways mirrored Georg Baselitz, his now better-known contemporary. Yet unlike Baselitz, Schönebeck never found a middle ground between the misplaced idealism of the East and the demands of the West. By 1967, his non-conformism caught up with him. He gave up art altogether.

This show—Schönebeck’s first solo exhibition in the United States—testifies to the abilities of an artist who channeled the spirit of the age into macabre paintings and drawings of singular dexterity and imagination. Abandoning the Soviet Realism of the East, Schönebeck first worked through Tachisme, Western Europe’s cooler answer to American Abstract Expressionism. In the early 1960s, these drips and drabs coalesced into nightmarish figures. He aimed “to let a certain tenor rise to the surface . . . a consciousness of crisis, pervasive sadness, gruesomeness, and even perverseness—that I found missing in the work of my colleagues.” With Baselitz, his fellow student, he wrote a pair of stream-of-consciousness manifestos called “Pandemonium” seeking to “point the way unerringly to the true meaning of freedom. / Flowers in the undergrowth. / The crematorium.”

Curated by Pamela Kort, the Nolan show follows this trajectory and focuses on the grotesque figure drawings of 1962 and 1963. The show is less than a survey. There is only one example, Mayakovsky (1966), from his late series of deadpan portraits dedicated (ironically?) to the icons of socialism. Schönebeck’s political evolution therefore remains unexamined, as do his reasons for leaving the world of art. Still, the dyspeptic mood he enunciated remains as current today as it did in the 1960s. One cannot but hope that this visionary, now living in Berlin, may once again put pen to paper and brush to canvas.