Dana Gordon, Some Talmud, 2012, oil on linen, 78" x 60"

THE NEW CRITERION

May 2013

Gallery Chronicle

by James Panero

On “Dana Gordon & John Mendelsohn: New Paintings” at Sideshow Gallery, Brooklyn, “Jane Freilicher: Painter Among Poets” at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, “Fedele Spadafora: New Paintings” at Slag Gallery, Brooklyn, and “John Dubrow: Recent Work” at Lori Bookstein Fine Art.

We live in an age that could use a few more heroes. Artists who pursue beauty regardless of the recognition they receive are heroes of a certain stripe. Of course, most serious artists fit this bill to one extent or another. Public appreciation rarely matches the effort that goes into what they make. Disbelief, even contempt, comes more often than praise. Just about any other form of labor offers an easier road to acceptance.

Yet even within this definition, there are those artists who receive fewer rewards than most. Over years and decades, they brush and hammer away without getting any of those commonly accepted tokens of artistic worth, be it a show, a review, or a sale.

What most impresses me about such artists is how the absence of these measures rarely reduces the quality of what they do. Often, the very lack of recognition clarifies and energizes the work. Their art becomes their reward. Freed from the requirements to please others, they create art that must be pleasing only to themselves.

Dana Gordon is an abstract painter who has developed along such lines. Over the years, I have seen him paint away in his home studios with little to show for it but the work on the walls. All the while, he has been slowly boiling down and reducing his homemade stock of shapes and colors. His process has been focused and determined, with a confidence in what comes next and a sense that things were going according to plan, even if he might not know how it would end up or just where it would all lead.

Dana Gordon, Night, 2013, oil on linen, 60" x 78"

Gordon’s arrival in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, with a front-room exhibition at Sideshow Gallery, is therefore both a noteworthy event and a long time in coming.1 The show opens at just the right moment. The paintings, variations on a theme Gordon has been mining for decades, have reached a vein of coloristic brilliance that calls out to be seen.

On top of a grid of colored tiles, Gordon lays down a free-form shape. Where the shape crosses a tile, the color appears to shift. Through this simple idiom, Gordon explores the underlying vocabulary of abstraction. He looks for the tension between the shape and the grid. Figure and ground, pattern and gesture, texture and form are all at play. The choices he makes are not so much programmatic as felt.

The amoeba-like form is free-handed and, in its scale, often relates to the dimensions of the body. A purple square turns green in one place but pink in another. A red one could go blue, yellow, or orange. The texture of the paint changes, with some spots left as thick pools of color while others are whipped and brushy. At each square, little paintings in themselves, Gordon determines how much of the shape comes forward or dissolves into the quilted pattern.

John Mendelsohn, Benefaction (detail), 2013, acrylic on canvas, 50" x 34"

As the exhibition follows Gordon’s development from 2009 to the present, one can see a progression from larger grids and frontal shapes to increasingly complex compositions. One of the most recent paintings, Some Talmud (2013), by the gallery entrance, features the tightest grid. Night(2013) dims the lights while also introducing a noticeable border to the grid, which forms a sort of compositional frame.

For me, the best painting is the large untitled one from 2012 at the entry to the back room—like Talmud, five feet wide and six and a half feet tall. Here the balancing act is near perfect. As we look to make sense of its shapes and colors, the painting shimmers between puzzlement and resolution—an Orphic kaleidoscope that demonstrates how Gordon’s long journey was worth the trip and how fortunate we are to see what has come of it.

Richard Timperio, the artist-owner of Sideshow, has wisely paired Gordon with finely crafted new paintings and works on paper by John Mendelsohn, which appear in the back room. With paint combed through with a white medium of pumice, Mendelsohn’s compositions convey an organic, pastoral calm. What appear as folds of wheat or drops of rain are, up close, refractions of color and stripes of paint. Sometimes Mendelsohn’s innovative paint handling takes over, and his work comes off as overly decorative. More often, he introduces just the right amount of unexpected color to give this two-person exhibition its wonder.

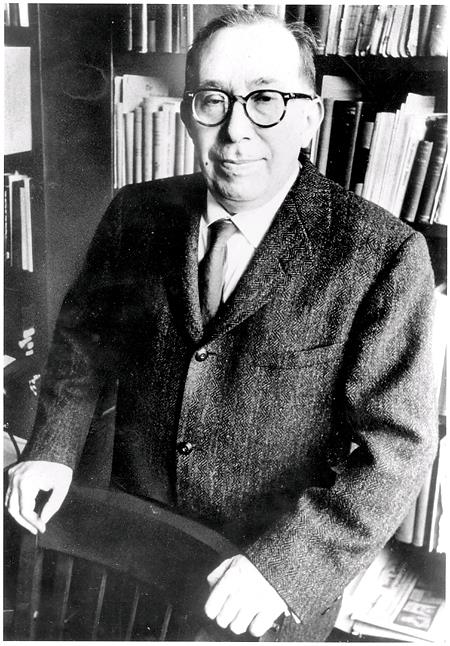

The challenge of a contextual exhibition such as “Jane Freilicher: Painter Among Poets” is just how the context should inform the art on view.2 The poets here are the New York School writers John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, Frank O’Hara, and James Schuyler—a circle that included Freilicher as a painter-in-residence starting in the late 1940s. In the case of Ashbery (born in 1927) and Freilicher (born in 1924), surviving members of the circle, this includes a friendship that continues to the present day.

Through correspondence, some of it collected along with books and manuscripts in display cases, we see how much the poets relied on Freilicher’s advice and friendship. O’Hara wrote a series of “Jane poems” with her name woven into the titles. For her part, Freilicher frequently portrayed the writers in her paintings. The exhibition includes her portraits of Ashbery (ca. 1954 and ca. 1968), Koch (ca. 1966), Schuyler (ca. 1965), and O’Hara (ca. 1951 and ca. 1967). (She once wondered if O’Hara’s “attractiveness was one of the reasons so many painters enjoyed knowing him.”)

Jane Freilicher, Portrait of Kenneth Koch, c.1966, oil on linen, 30 x 40 inches

No other gallery but Tibor de Nagy could mine this territory so expertly. The gallery mounted its first exhibition of Freilicher’s work in 1952. The gallery’s namesake, along with John Myers, De Nagy’s gallery partner from 1951 to 1970, was part of this same large circle of painters and poets. The exhibition also includes a hundred-page catalogue with an extensive essay by Jenni Quilter, an academic who has focused on the New York School poets and their connections with visual artists.

The exhibition steers clear of drawing too easy a connection between the visual and written work. “My poet friends didn’t influence me directly,” Freilicher explains through the catalogue. She “followed her own path,” says Ashbery, “with stops along the way to take in Bonnard, Balthus, Watteau, and even, unless I’m mistaken, Hofmann himself.” “Like a shout across a body of water,” writes Quilter, “we cannot trace these echoes back to their source, and nor would we really want to.”

The cross-connections are more about tone than substance. Freilicher identifies a shared “sympathetic vibration, a natural syntax—a lack of pomposity or heavy symbolism—and something to do with intimism, an intimate kind of expression.” Quilter writes of their “gracious existence composed of the pleasures of the good life: beautiful things, fine food, excellent company.”

This lightness and intimacy that Freilicher brought to the circle becomes clear early on. Her appearance in two sketch comedies filmed by Rudy Burckhardt in the early 1950s, screened in the gallery’s back room, demonstrates how, as a serious artist, she still never took herself too seriously. Her style was clearly different from New York’s hardboiled abstract painters of the 1940s; such machismo, she said, was “not terribly interesting” to her. Reviewing her 1952 exhibition at Tibor de Nagy, Fairfield Porter wrote how Freilicher was “trying to rediscover first principles. Her painting is traditional and radical.”

Jane Freilicher, Study in Blue and Gray, 2011, oil on linen, 24 x 24 inches

In her intimate work, Freilicher was unafraid of small statements. “A can of coffee, a 35¢ ear/ ring, a handful of hair, what/ do these things do to us?” wrote O’Hara in his “Interior (with Jane)” in 1951. Freilicher’s paintings have always “lacked that authoritarian look, public-spirited and public-addressed, stamped on so much postwar work like a purple ‘OK to Eat’ on a rump of beef,” Schuyler colorfully concluded. Instead, Freilicher finds greatness in vignettes—in Long Island landscapes, and in glimpses from her studio overlooking the rooftops around New York’s Union Square. As the window on a circle of poets, she also offers a view that is equally inviting.

Fedele Spadafora is a realist who brings a modern sensibility to classical training. A former student of Nelson Shanks and his Studio Incamminati, Spadafora uses the tools of realism to explore the modern landscape.

The transmission of both television and memory—and the qualities they share—are recurring themes in his work. Recently, Spadafora painted a series of portraits of Ian Curtis, the tragic hero of punk rock, as though appearing in the degraded off-color image of a videotape.

Fedele Spadafora, Prague, 2013, 26 x 18 in, oil on canvas

For his exhibition of new paintings at Slag, a gallery now in the 56 Bogart Street building of Bushwick, Spadafora revisited trips he made through Prague and Tunisia.3 The Tunis paintings, with their blue skies, white fireballs, and orange bridges, bring too much to the canvas. Here memory comes off as a muddle. Far more successful are the paintings based on old snapshots from Prague, where he lived just after the fall of Communism.

The Žižkov Television Tower, a monument to the high-tech authoritarianism of the former regime, appears in several works. In each painting, the tower is bathed in cobalt blue, as though irradiated in microwave signals. This is Spadafora at his best, with a realism zapped with the realities of technology and its role in how we remember the lives we lead.

Walking through the exhibition of the recent work of John Dubrow, I couldn’t help but notice two old columns cutting through the middle of his Chelsea gallery.4 Compared to the pristine white box walls of the space, the fluted columns were coated in layers of paint, some of it splattered and much of it trowelled on through what must have been the long and varied history of an old dockland building.

John Dubrow, Central Park, 2011-13, Oil on linen, 20" x 24"

My guess is that Lori Bookstein Fine Art chose to leave these columns in their roughed-up shape for the same reason that I find Dubrow’s cityscapes so beguiling. Beneath the surface, peeking through in layers of paint, is the mystery of what came before.

Dubrow builds up his paint, often over years, to the point where his canvases appear to bend from the weight of their own creation. He applies oils with the knife and returns to his compositions repeatedly to move his cast of characters around the streets, playgrounds, and parks they inhabit. The accretion speaks to the process of painting and animates the work. These canvases have a history.

John Dubrow, Hudson River Park, 2012-13, Oil on linen, 30" x 40"

Dubrow’s paintings are worked over but not overworked. Rather than correct all of their imperfections, he leaves his paintings with a raw intensity. This is especially true in Hudson River Park (2012–13), where one can clearly see how the figures have been revised and shifted. Central Park (2011–2013) dissolves into a Pointillist riot the closer one gets. These paintings are landscapes in relief. A third dimension of paint gives meaning to the other two and completes the work, just as the images are left undone.

1 “Dana Gordon & John Mendelsohn: New Paintings” opened at Sideshow Gallery, Brooklyn, on April 13 and remains on view through May 12, 2013.

2 “Jane Freilicher: Painter Among Poets” opened at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, on April 13 and remains on view through June 14, 2013.

3 “Fedele Spadafora: New Paintings” was on view at Slag Gallery, Brooklyn, from March 22 through April 18, 2013.

4 “John Dubrow: Recent Work” was on view at Lori Bookstein Fine Art, New York, from March 21 through April 20, 2013.