Artists are a swarming species. There’s a reason why, a century ago in Montparnasse, the main studio building was called La Ruche, or “The Beehive.” While great art can, of course, emerge in isolation, more often it comes out of hives of activity—dense, furious places, usually frightening to outsiders, that must be surrounded by just the right kind of environment. And for several generations, it is safe to say, the largest swarm has settled in New York. Certainly, from time to time, the actual location of its hive has moved—from Tenth Street, to Spring Street, to the East Village, to Williamsburg and Bushwick. But since the 1950s, the living arts have fed off the same citywide ecosystem.

Which goes to show you how unpredictable artistic swarms can be. New York has always been a city of both nectar and insecticide. No other place may be so sweet to artists while at the same time striving to kill them off—its environment rich in resources but unsentimental towards artists’ habits and needs. Of course, particularly harsh circumstances may account for the tenacity of art in New York. The arts have thrived despite, not because of, what New York offers.

This is not to suggest the swarm is ever stable; great art is a fragile product. The buzz on the ground only tells us so much about the health of the hive, and swarms move in unpredictable ways. A few distant bees may just be out for a long day, or they may end up relocating the whole hive—La Ruche, au revoir.

In New York, the talk has always been, Where to? How much longer? What’s next? The city’s imminent artistic collapse is a perennial topic of conversation. So far, the artists have largely stayed within city lines, even as they have moved to its outer limits. But a handful of busy bees have been going even farther afield—up to the country where they nest in the eaves of barn studios, or off to municipalities with exotic names like Hoboken.

To put the city of Philadelphia in this final category may be as New York–centric as it comes. Philly was an art town before New York had a canvas to paint on. Founded in 1805, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts remains America’s oldest art academy and museum. Its singular headquarters, designed by Frank Furness in the 1870s, continues to be a hive of activity. Its best-known student and teacher, Thomas Eakins, may be the single greatest painter in American history.

With grand boulevards cutting broad sightlines through tight city streets, Philly has had the cultural ambitions of imperial France. Philadelphia’s City Hall is a cacophony of Second Empire striving and is said to be the tallest masonry building in the world—a reason that, through gross tonnage, it has escaped the wrecking ball. The city has also long placed the arts and sciences, for better or worse, at the heart of its civic identity (and municipal meddling). The Philadelphia Museum of Art, one of the greatest encyclopedic museums to come out of the nineteenth century, now looks down the Benjamin Franklin Parkway at the city’s latest (and, to some, most infamous) artistic acquisition: the relocated Barnes Foundation.

Philadelphia’s centralized cultural outreach, now called Visit Philadelphia, is today the envy of all museum towns—and a convincing one at that. So this past month, I took this column to Philadelphia (meaning I must pass over the latest New York appearances by Loren Munk at Freight + Volume, Austin Thomas at Hansel & Gretel, and Deborah Brown at Lesley Heller—not that you should.)

I never intended the “Gallery Chronicle” to be soley about New York, after all, but it goes where I go, and most months I travel no farther than a New York City subway ride. As the vibrancy of art in New York has been pushed to the margins, with an alternative scene now flourishing in the outer boroughs, Philly is sometimes talked about as the “sixth borough” for its ability to offer artist-friendly space, at artist-friendly prices, in a city that trumpets its artistic infrastructure. I’m sure Philadelphians don’t think of themselves that way, but it helps us New Yorkers to see the world as an extension of our streets rather than as unique places. There’s even a website, called extendny.com, that will lay the Manhattan grid over the entire globe and calculate every avenue and cross-street.

I should say here that my weekend survey of Philadelphia’s gallery scene was anything but scientific. With only a general sense of where to go, I found myself sounding the social-media siren the morning of my arrival. Fortunately, in what I gather is called “crowdsourcing,” the recommendations came pouring back in. The Brooklyn-based painter and curator Paul Behnke, who lived for several years in Philadelphia, was particularly insightful. I also found online resources such as theartblog.org to offer an excellent guide to the city’s contemporary highlights. Unfortunately, from the moment of my arrival, which was the first weekend in February, I came to understand that I had come at somewhat the wrong time. Philly’s gallery scene is coordinated to such an extent that almost all its shows open on the same “first Friday” of the month—and I was there on the last Saturday.

Sarah Sze at Fabric Workshop

That means I never made it to some highly touted spots, such as The Icebox Project Space in the Crane Arts building. My regrets also go out to Fjord, another space in Fishtown. I did see the Fabric Workshop, thanks to a suggestion by the fabric artist Brece Honeycutt, and I’m glad I did. The current installation by Sarah Sze, who was an artist in residence, might have little to do with fabric but seemed to employ just about every other material—newspapers, stones, ceramic particles—to build up and break off systems of significance.

Here an entire floor is filled with boulders that are really (for the most part) hollow sculptures covered in digital mylar printouts of rocky moss-covered textures. What did it mean? I didn’t really care, because the technique alone was so intriguing and the sense of it so unnerving, with massive forms that weighed almost nothing.

Grizzly Grizzly

Another curious space I passed through was a grimy gallery building at 319A North 11th Street, which I dub “Little Bushwick,” home to such artfully named startups and cooperative spaces as Vox Populi, Marginal Utility, Grizzly Grizzly, and Tiger Strikes Asteroid. I’m sorry TSA wasn’t open, since its exhibition of molded sculptures by Benjamin White looked promising. What I saw at Vox Populi left me underwhelmed, while Grizzly Grizzly’s white cave of oddities by Trevor Amery, sculptural work of mirrors and plaster (I think) “that questions our relationship to discreet art objects and challenges our role as passive art viewers,” as a press release said, left me scratching my thick bear head. I did respect the fact that the gallerist in attendance had no chair and had to sit with a laptop on the floor.

Installation view at Larry Becker

My visit to Larry Becker Contemporary Art in Philadelphia’s Old City was a knockout—in the sense that once I walked in, and got wrapped in conversation with its co-founders Larry Becker and Heidi Nivling, it was several hours before I regained my senses to move on. The gallery, which celebrated its thirtieth anniversary in February, reflects the city’s do-it-yourself art scene at its best. Becker and Nivling met as students at Philadelphia’s Tyler School of Art and decided to return after graduate studies, buying a small factory building with a ground-floor exhibition space. Here their program has focused on serious, reductive painting, the kind of labor-intensive studio practice that seems right at home in the painted, scraped back, and painted-over environment of Old City.

Detail of Steve Baris work at Pentimenti

On view through March 15, Becker has brought together nine such painters for an exhibition called “In Daylight.” With work by Eve Aschheim, Karen Baumeister, Anna Bogatin, Dove Bradshaw, Max Cole, Ruth Ann Fredenthal, Martha Groome, Kazimira Rachfal, Merrill Wagner—some new, many returning—the exhibition offers an excellent overview of what this gallery is about. With mostly small, meditative work, the exhibition draws extra attention to the subtleties of light on paint, showing at least one work by each artist in the front window. (Behind the desk at the nearby Pentimenti gallery, I stumbled upon an interesting painting by Steve Baris—accompanied by the artist himself—that worked with many of these same ideas.)

Portrait of Eadweard Muybridge at Gallery Joe

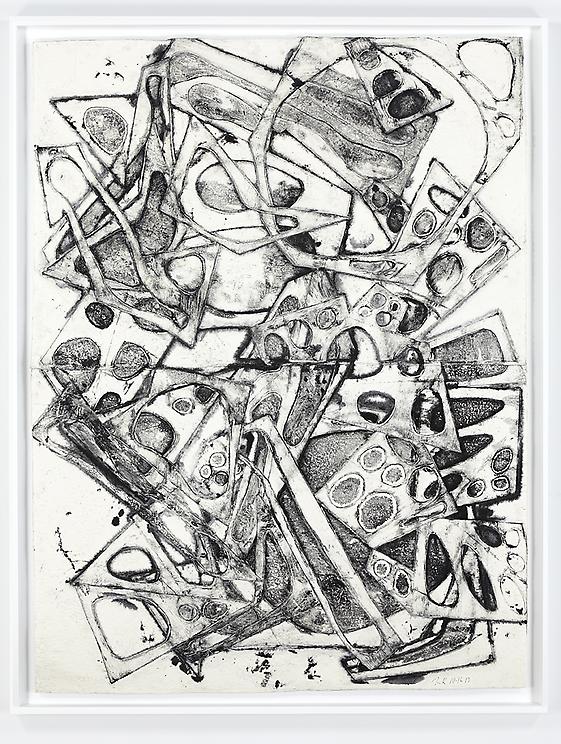

I found something similar at Gallery Joe, another Old City space that came recommended and which opened the doors of its current exhibition early for me. Gallery Joe’s focus is works on paper, and Mia Rosenthal, now on view, offers the kind of paper-working I find extra enjoyable.

Part draftsmanship, part note-taking, in “A Little Bit Every Day” Rosenthal reprocesses the furtive images of online landscapes back into items of craft. She draws “portraits” of people’s laptops and smart-phone screens. She layers pictogram over pictogram of the world’s evolving, spiraling species, including tiny handwritten labels, in extremely dense drawings such as Life on Earth (2013). She also makes composite sketches of online image searches. Her Google Portrait of Eadweard Muybridge (2013) here works best, as Muybridge’s famous stop-frame photography gets repeated over and over in search results, which Rosenthal freezes in pencil and ink.

Detail of Yeesookyung sculpture at Locks

No tour of Philadelphia’s gallery scene would be complete without a visit to Locks, founded in 1968, and by far the city’s largest (only?) blue-chip international gallery. The building itself is stunning—a historic, neoclassical facade overlooking Philly’s Washington Square Park, leading onto multiple floors of spare, loft-like space. Again, my timing here could have been better. An exhibition of paintings by Nancy Graves was just coming down, while all that was left of an installation by Rob Wynne were hundreds of nails in the wall. At the same time, the current Robert Rauschenberg exhibition, focusing on a worldwide tour he made in the 1980s called the “Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange,” was still in the shipping containers.

I did, however, get a glimpse of its other current show, by the Korean artist Yeesookyung. There’s undoubtedly a style of international art that takes some local craft, often an expensive one, and recasts it through a contemporary pop aesthetic. Yeesookyung’s sculptures made from shards of oriental pottery, held together with gold, would seem to fit in this category. But Yee’s sculptures, crafted from imperfect, cast-off fragments of contemporary Joseon Dynasty–style porcelain and Goryeo Dynasty–style celadon, transcend this obvious framework with hauntingly ephemeral, dynamic, bubbling forms. To borrow a phrase once reserved for Duchamp’sNude Descending a Staircase (now another Philly resident), Yee’s sculptures resemble an explosion in a teacup factory.

If I were to single out one factor that seemed to be missing from most of these Philadelphia exhibitions, it would be the pressure of the market that one feels in New York. Larry Becker and Heidi Nivling, after all, call themselves gallerists, not dealers: Their focus is on showing art, not selling from a back room. The dominant style of art in Philadelphia, Nivling says, is no style. With less of an imperative to follow the trends, Philadelphia’s artists and dealers have a greater freedom to show what they like. Taken together with its great museums and peerless orchestra, the arts of Philadelphia certainly reverse those old W. C. Fields jokes that have been made at the city’s expense. From here on out, second prize is a week in Philadelphia, and first prize is two.

“Sarah Sze” opened at The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, on December 13, 2013, and remains on view through April 6, 2014.

“In Daylight: Small Paintings” opened at Larry Becker Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, on December 28, 2013 and remains on view through March 15, 2014.

“Mia Rosenthal: A Little Bit Every Day” opened at Gallery Joe, Philadelphia, on February 7 and remains on view through March 22, 2014.

“Yeesookyung: The Meaning of Time” opened at Locks Gallery, Philadelphia, on February 7 and remains on view through March 15, 2014.