THE NEW CRITERION, February 22, 2019

Finger Painting with a Broad Brush

On Dana Schutz’s “Imagine Me and You” at Petzel Gallery.

If you are looking for a controversial artist, you wouldn’t necessarily point the finger at Dana Schutz. Nevertheless, and rather surprisingly, controversy pointed at this painter and sculptor at the last Whitney Biennial. In an exhibition that was asking for trouble with far more “controversial” work, Open Casket, Schutz’s memorial portrait of Emmett Till, the black boy who was infamously murdered and mutilated in Mississippi in 1956, took top prize for consternation and column inches. A British agitator named Hannah Black published an open letter to the museum’s curators and staff, co-signed by some fifty other writers and artists, “with the urgent recommendation that the painting be destroyed and not entered into any market or museum.” Aspiring censors the world over came together to declare that “white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights. The painting must go.” A Twitter mob even materialized to form a human chain to block the painting from public view.

Schutz took refuge in the studio. Nearly two years on, the Michigan-born, Brooklyn-based painter has reemerged with a pointed exhibition of new work at Petzel that is impressed with personal experience. “Pointing” and “pressing” are the operative works. In this show called “Imagine Me and You,” on view through February 23, the finger appears throughout as both the instrument of accusation and creation.

Dana Schutz, Painting in an Earthquake, 2019, Oil on canvas, Petzel Gallery.

Schutz is a facile artist. In the past her paint handling has often seemed confectionary, easily digestible and saccharine sweet. Her rich colors and cartoonish forms have been the icing on a cake that is only half-baked. The Whitney experience has now added heat to the oven.Painting in an Earthquake (2019), the show’s introductory painting, is but the first of its many self-portraits. With paint brushes in her left hand, a figure smears paint on a shattering brick wall with the fingers of the right.

The exhibition then leads on to a room not of more paintings, but of figural sculptures in bronze. As these grisaille forms contrast with the colorful oils, they also illustrate the sculptural qualities of Schultz’s heavily impastoed canvases, which are often paintings in sculptural relief. The sculptures also give further form to some of the figures that later appear on canvas, such as in Washing Monsters (2018).

Dana Schutz, Washing Monsters, 2018, Bronze, Petzel Gallery.

Schutz comes out of the Brooklyn school of casual figuration. Whether in two dimensions or three, in their faux naivete, some of her cartoonish figures can seem overly mannered. At the same time, the surface expression of these bronzed objects, created first in soft molding compound, conveys personal meaning through their pressed forms. Schutz’s fingerprints are all over these crude displays.

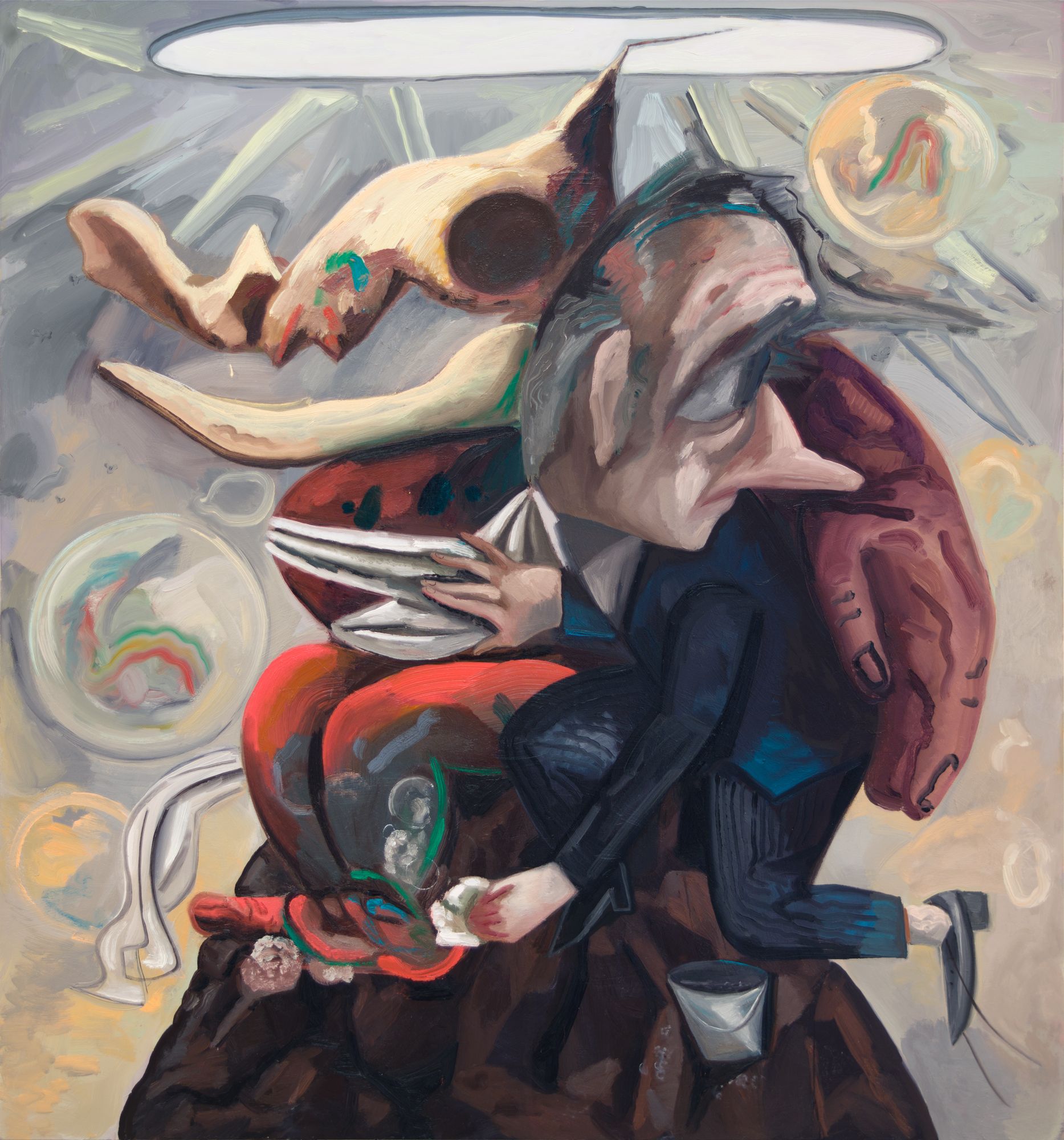

Dana Schutz, Washing Monsters, 2018, Oil on canvas, Petzel Gallery.

The personal nature of these expressive surfaces is then carried over to Schutz’s paintings in the next room. Touched (2018) is both a subject and object of self-portraiture. A female figure faces out with a carved frown as Schutz gouges out the breasts of thick paint with two fingers.

Dana Schutz, Touched, 2018, Oil on canvas, Petzel Gallery.

Fingers appear as symbols throughout this body of work. The naked shipwrecked female figure in The Visible World (2018) dips one digit in the forbidding water. Another points to a gull with a berry in its beak and a daubs of paint across its wings. In Presenter (2018) the fingers of a disembodied hand muzzle a female figure with underpants pulled down around the ankles. Meanwhile, in Mountain Group (2018), at ten feet wide the largest painting of the exhibition, an ensemble cast of finger-pointers on ladders obscures the mountain landscape that a female painter in the foreground, with canvas and brushes, is trying to depict.

Dana Schutz, Treadmill, 2018, Oil on canvas, Petzel Gallery.

Turn around and the last painting you see is Treadmill (2018), with a figure trying to keep up on a fast-moving paint-splattered ground. At a time when anyone may be called out for deviations from the party doctrine of race politics, this exhibition points the finger at a new censorious age.