THE NEW CRITERION, December 2019

On American architectural style.

I like to go “housing” the way many people go birding. What I mean is, I like to classify and call out house styles as I come upon them in the wild. Granted, my hobby is not too popular with my family, who could do without my outbursts of architectural enthusiasm, but our country is fertile ground for good house-watching. Fine examples, of just about any style of any period, abound. What stories they tell if only we listened to their calls.

Take the Colonial, with its simple shapes and rustic materials. These tiny dwellings still betray the bare necessities of early settler life, all flattened into a landscape of rectangles and triangles and parallelograms. Or consider the Georgian, with its proud symmetries square-shouldered to the door. These stoic structures imposed classical order on the new republic and the nascent Federal style. Or how about the Greek Revival, the subsequent divination that seemed to sweep through every New England farm: its delicate upward lines, pedimented white gable fronts, and off-centered doors rotated the house a quarter turn like an altered state. As the country grew, so did its worldview, and later styles looked in ever more head-turning directions: to the Italianate and the Second Empire, on to the Queen Anne, the Romanesque, and the Exotic Eclectic, on to the Beaux-Arts and the Chateauesque, on to their many blends and crossbreeds.

Like unusual plumage, the subtle details in each of these styles give the greatest delight: the lace-like vergeboard dripping off the projecting gables of a steeply pitched Gothic Revival; the glowing belvedere—from the Italian for “beautiful view”—popping out the top of some bejeweled Italianate box; the sunbursts and spindlework woven into the turrets and trusses of the Queen Anne. Among these happy sightings, my favorite of all is that rara avis: the Stick style, with its toothpick-like details, so named after the fact by Vincent Scully, that came and went in a flash in the later nineteenth century.

I find the tidy styles of the twentieth century, both revival and modern, often lacking the same free spirit: “Stockbroker Tudor” I could do without; the Craftsman and Foursquare can be clunky and junky; the much-touted Prairie style I regard as oppressively flat and dark. Standardized housing plans and mail-order designs led to stylistic over-breeding, which the moderns tried much to exterminate. Yet ultimately, what resulted was not some ascetic paradise but rather a post-apocalyptic landscape of surviving flora and fauna, including those irradiated forms known as McMansions, all jostling for space among what remains of our grand architectural menagerie.

Like a birder, the “houser” must be equipped with a taxonomic dictionary. Like the “Sibley,” the “Peterson,” or the “Kaufman” birding guides, everyone has a preference. Virginia Savage McAlester’s Field Guide to American Houses, revised and expanded in 2015, may be the gold standard for housing typology. In addition to offering hundreds of thumbnail examples of just about every form of American home, the guide presents pictorial keys and glossaries to help identify the style of any house found in the bush. The book also dilates in interesting ways over housing stocks I rarely consider, such as manufactured mobile homes, which for reasons of climate are found in the greatest numbers in the South and West. Today one in ten American homes is prefabricated. In many warmer areas, more than 20 percent of dwellings are now factory-made and highway-delivered—even though the end result, such as the “decorated double-wide with extensions,” little resembles what we think of as a “mobile home.”

For picture pleasure, I enjoy William Morgan’s accessible Abrams Guide to American House Styles (2008). American homes tell a story behind their styles. Morgan captures this with a light touch and colorful photography. “A temple in Vermont marked the success of a sheep farmer,” he writes of the Greek Revival, while such a house “in Ohio’s Western Reserve showed that the new settlers were planning to set down roots for the ages.” Morgan also rightly notes that “one of those rich ironies in which American architecture abounds is that, in reaching deeper and more seriously into the classical and medieval past for inspiration, our houses became more particularly American.” The American-ness of these historical forms is what the International Style found most “dishonest.” Nevertheless, American architecture continued to “revive” its historical styles, because “so many in search of the American dream were willing to have it interpreted by Colonial Williamsburg, Sears, or a shelter magazine, but not by a European-trained professor.”

For the story of style, John Milnes Baker says it best in American House Styles: A Concise Guide, updated in a new edition last year. Supplemented by his own elegant elevation drawings, Baker reveals how American homes adapted the treasure trove of Old World influence to the climate and resources of the New. With an abundance of forests, timber often replaced brick and stone in domestic construction. Meanwhile the harsher American climate, intemperate to both extremes, introduced covered porches, shingled rooflines, and breezier, more convertible floor plans compared to our European prototypes. Baker’s book pays homage to our architectural inheritance in the same way our best buildings do: “Our houses have been shaped by their architectural forebears as much as we as individuals are shaped by our genetic and cultural backgrounds.”

In the summer of 1877, Charles Follen McKim, William Rutherford Mead, and Stanford White embarked on a now-celebrated sketching tour of coastal New England north of Boston. Their observations of buildings in Salem, Marblehead, Newburyport, and Portsmouth fueled the Colonial Revival and forged their own architectural partnership two years later. The New England coast has always offered promising house-watching grounds. This is especially true as Victorian-era summer homes came to roost among the older vernacular styles. Here, warm-weather feathering could be in greatest display apart from the concerns of year-round shelter. My summer haunt of Block Island, Rhode Island, still abounds in fine examples of Gothic Revival and Queen Anne houses—not to mention some of my favorite Stick- and Shingle-style buildings. These are all mixed in among Second Empire hotels and the many Colonial and Greek Revival forms dotting the landscape.

This past summer, I ventured farther afield by following the stylistic flyways north, to Portland, Maine. I have a theory that historical houses are often best preserved in cycles of boom and bust. Too much continuous growth and history gets wiped away. Too little and houses fall apart or never aspire. But success followed by stagnation followed by renewed prosperity can preserve interesting houses in amber just long enough for them to be rediscovered and restored.

The 1801 McLellan House in Portland, Maine, which has stood the test of time. Photo: Portland Museum of Art.

So it has been for Portland more than once. As the northernmost Atlantic port navigable in winter, the city offered early year-round access to the Canadian interior. Its landscape was then shaped by four cataclysmic fires, the last of which was caused by fireworks set off on Independence Day, 1866. The fire leveled the city’s commercial center, destroying 1,800 buildings and displacing 10,000 residents. Meanwhile, the city’s shipping, industrial, and tourist economies have come and gone and come back several times. Today the city is again experiencing a cultural renaissance, in particular one centered around its cuisine. This renewal now finds root and flowers among the city’s many historic houses.

A good place to start house-watching in Portland is at the corner of High and Spring Streets. That’s just what I did when I signed up for a walking tour offered by Greater Portland Landmarks, dedicated to the preservation of the city since 1964. The organization’s motto is “this place matters.” Standing at High and Spring, you can see why this advocacy is important. Just to the northeast, a wave of “urban renewal” marched up Spring Street almost to where we stood—part of an ill-fated scheme to run an arterial road through the heart of the old city. With consequences far worse than the 1866 fire, in the 1970s the urban planners laid waste to this historic neighborhood and left a landscape of reinforced concrete, parking garages, and a Holiday Inn.

Yet their march stopped just short of this key intersection, which still maintains some of the finest buildings from Portland’s successive architectural eras. To the north, at 111 High Street, is the McLellan House of 1801. In this three-story brick building, the delicacy of the Federal style is revealed in abundance, with the organization of the Georgian style flattened and refined. For comparison, the 1755 Tate House, a few miles away and now a house museum, offers a far more rustic Georgian interpretation. Constructed for the senior mast agent for the British Royal Navy, who oversaw the cutting and shipping of Maine white pines to England, the unpainted clapboard Tate House sports unusual but picturesque subsumed dormers in its gambrel roof.

The 1755 Tate House in Portland, Maine.

Compared to the stout massing of the Tate House, the McLellan House offers delicacy at every turn. A second-story Palladian window balances above a semi-circular portico of slender Doric columns leading up from sandstone steps. A gently tapered balustrade topped with tiny urns around a low-hipped roof completes the ordered composition. Designed by John Kimball, Sr., of Ipswich, Massachusetts, the home was built for the shipping magnate Hugh McLellan. In the later nineteenth century, the McLellan House was purchased by the wonderfully named Lorenzo De Medici Sweat, a U.S. Representative from Maine. In 1908, his widow bequeathed the brick home to the Portland Society of Art, which added a memorial gallery that evolved into the Portland Museum of Art, now fronting Free Street. So while it takes some internal navigation to get there, the house is now open simply with a ticket to the museum, which recently restored the mansion’s Federal details. Touring its interior completes the picture, since the house’s order outside mirrors its order within. Centered on the front door and its Palladian window is a free-standing staircase that seems to levitate from the first floor to the second. Light, and lightness, is everything here.

Just to the east of the McLellan House, at 97 Spring Street, is the Charles Q. Clapp House of 1832. The house was likely designed by its eponymous first owner. Clapp was so committed to Greek Revival that he created a free-standing Corinthian colonnade to run along the two sides of his home, curiously narrowing his living quarters beneath a gabled pediment. The front entrance, not just pushed to the side but around a corner, lends a masonic mystery to this latter-day temple. I hope this building, now under the ownership of the Portland Museum of Art like the McLellan House but used for storage, might one day be opened to the public.

Across the street, at 93 High Street, the Safford House of 1858 offers a later example of Portland high style, this time in the Italianate. The building is now both the headquarters of Portland Landmarks and one of its restoration projects, offering exhibitions on the preservation of the city. I wouldn’t necessarily have expected them in New England, but Portland offers an abundance of Italianate buildings, all at one time built as private homes but having served and suffered a multitude of uses since. The Morse-Libby House, known as Victoria Mansion, is the finest and open to the public.

The Morse-Libby House, also known as Victoria Mansion, built ca. 1859. It still stands today.

There are now eighty historic landmarks in Portland. In addition to offering walking tours, the Landmarks society hosts an interactive online map documenting them all. But there are still more houses of note than merely the eighty. Although not advertised as such, my boutique Italianate hotel on Congress Street in Portland’s reviving West End, built in 1881 for Mellen E. Bolster, served most of its life not as a gentleman’s residence but as a funeral parlor.

While the city now shows remarkable signs of life, there remain those symbols of misuse and decay, especially in the population of vagrants—pickled, salted, and sauced—who still tumble through its historic streets. The revival of this city from wholesale destitution is very much a testament to its historic architecture, which is buoying it up from the depths.

Just what will endure from today’s house styles remains a point of contention. What became known as the Millennium Boom introduced speculative specimens into barren deserts and fallow farmlands and leveled historic lots in existing neighborhoods. Not the austere modernism of the elite, nor even the jokey post-modernism of the effete, these houses were often designed for maximal square footage and maximum “curb appeal” through a minimum of stylistic felicity, unironically deploying historical style—sometimes, seemingly every style compressed into one building. Called McMansions for their cheap ingredients and unavoidable ubiquity, these houses have marked out a new American style that is now already in eclipse (giving way, I understand, to more refined “McModerns”).

I like to call the McMansion style “Queen And.” These buildings are driven by the extensive list of demands placed on their interior spaces: private wine cellars and media rooms and art rooms and workout rooms and family rooms and man caves and fire pits and utility kitchens and Peloton rooms must all exist side-by-side a full set of more formal, but unused, spaces. In response to the low ceilings of a previous generation of modern houses, these homes feature overly high ceilings and double-height entryways leading on from two-story-tall porticos, one of the hallmarks of the style. The houses are pushed from the inside to the breaking point. Architects and builders conceal the girth under a multi-layered drapery of false, historic-esque façades.

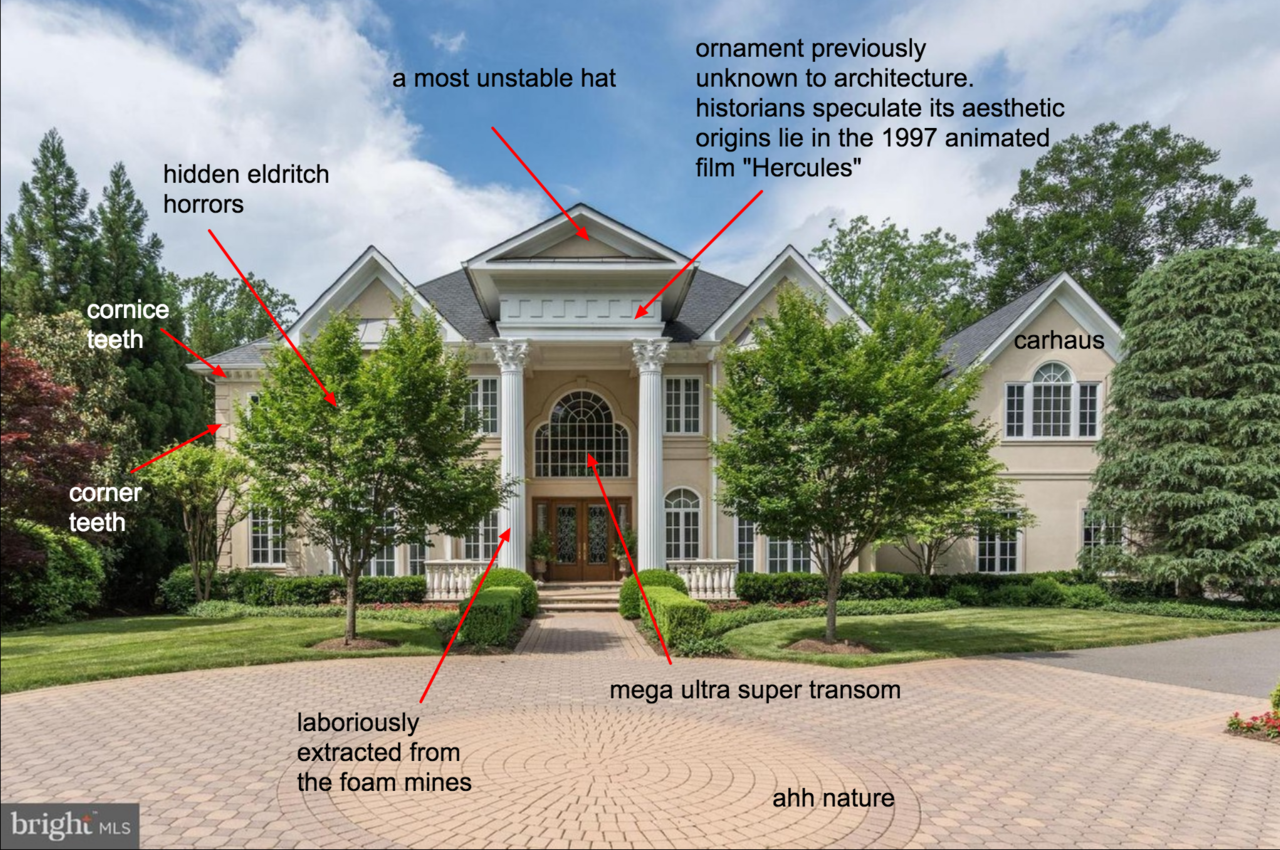

The “Queen And” has justifiably gone in for a beating. I laugh along with most everybody else at the putdowns offered by McMansion Hell, the website created by Kate Wagner that revels in all the “lawyer foyers,” roofline “nubs,” and cast-styrofoam details. The style guidebooks can be as equally damning of these frankenhomes. “Does adding a Palladian window to the balloon-frame house covered in polyvinyl siding make it a Georgian house?,” asks William Morgan. “Does mixing several styles in a single house cloud the lessons the past style might have to teach us? . . . McMansion developments are like Potemkin villages: all façade, designed to impress.”

A variety of McMansion local to Fairfax County, Virginia, as documented by the architectural critic Kate Wagner. Courtesy McMansion Hell.

And yet, I see some hope in these architectural jumbles. “Queen And” houses may speak gibberish, and in them the mockers see much bourgeois striving, but such homes nevertheless reveal a yearning for a lost language. I am reminded of the history of the Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum. First built in 497 B.C., the temple was resurrected several times, most recently after a fire in 360 A.D. But that final restoration, done in the waning days of pagan revivalism, went a little wrong at every turn, with bits borrowed from prior buildings and column heights and widths all inconsistent with ancient classical order.

The McMansion is likewise built for a population that might still recognize the ancient sounds of architecture but not its language and certainly not its style. John Milnes Baker likens good architectural style to good writing. The proper guide can instruct in each, in ways that go beyond mere style: “Houses should have more substance than style,” he writes—

Let’s not worry so much about what particular style our houses are; let’s trust that they will simply have style—an inherent, intrinsic style that derives from the nature of the materials used and an expression of the spaces defined. . . . Throughout our history, our best houses have derived elegance from simplicity, dignity from restraint, and richness from subtle diversity.

The challenge for the future of the home is therefore not just a revival of style but also a revival of substance. Historic orders require an ordering of the lives contained therein. But done right, the chaos of an open-plan, open-access, hyper-connected world may be partitioned and controlled through classical proportion and domestic order. Beyond mere style, our architectural forebears understood these attributes of the home. Their examples still sing to us from the wild. We should listen to their calls.