THE NEW CRITERION, March 2022

On “Leon Kossoff: A Life in Painting” at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, “Rodrigo Moynihan: The Studio Paintings, 1970s & 1980s” at David Nolan Gallery, “Paul Resika: Self-Portraits, 1946–2021” at Bookstein Projects, “Paul Resika: Allegory (San Nicola di Bari)” at the New York Studio School & “Drawings: Rackstraw Downes” at Betty Cuningham Gallery.

London modernism doesn’t get the same credit as its Paris or New York counterparts. That only means the work of the richly expressive painters of the London School—not just Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, but also Frank Auerbach, Michael Andrews, and R. B. Kitaj, among others—continues to surprise. “Leon Kossoff: A Life in Painting,” at New York’s Mitchell-Innes & Nash, provides a deep dive into the thick impasto of this British painter.1 Born in London in 1926, and focused on the lives of its working-class neighborhoods, Kossoff imparted the weight of experience in the thickness of his line and heaviness of his brush.

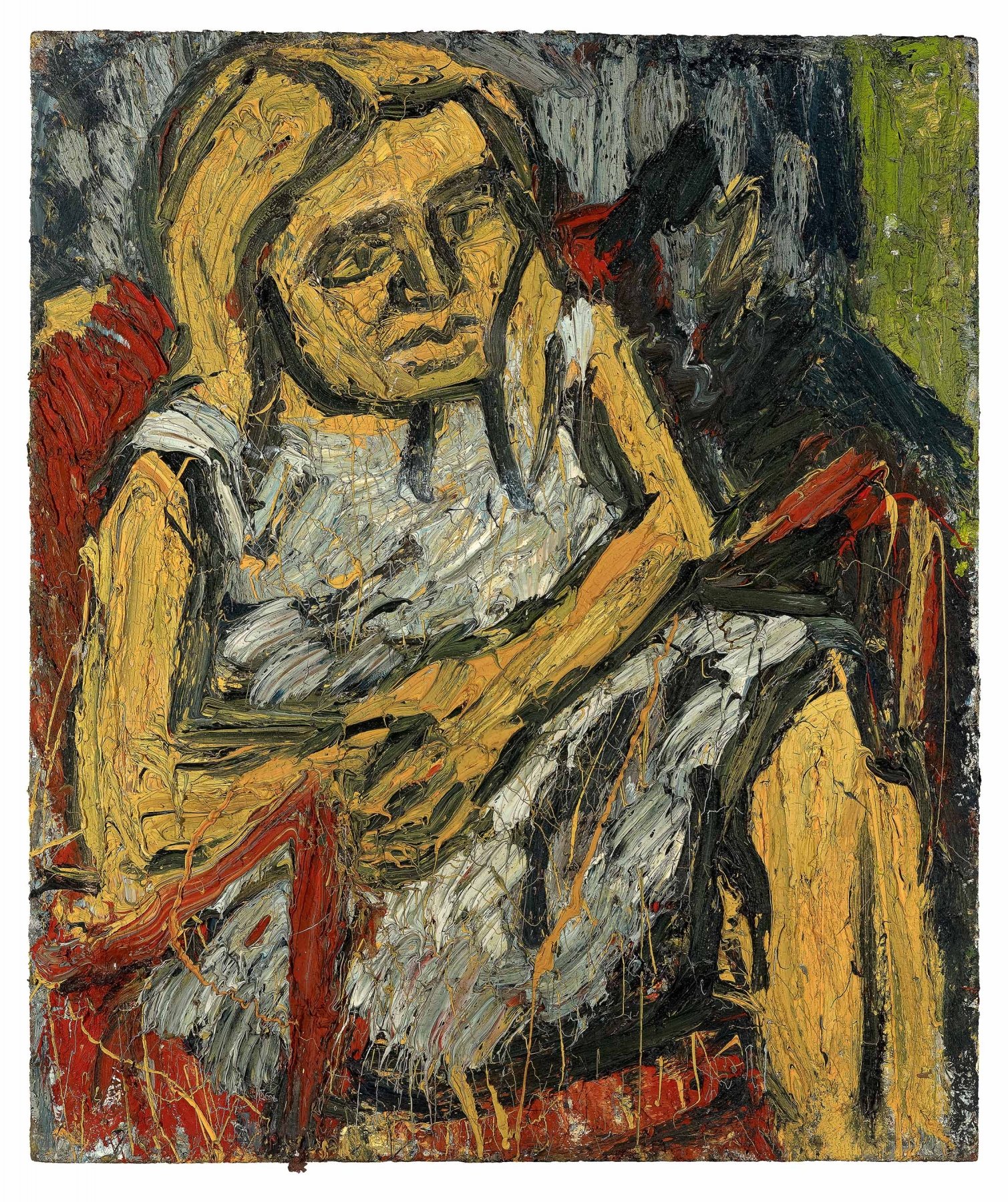

Leon Kossoff, Portrait of Rosalind No. 1, 1973, Oil on board, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

The exhibition of sixteen works, ranging from 1963 to 1993, is a revelation of painterly expression. English artists have never shied away from painting the gutter—sometimes from the gutter. Kossoff, who died in 2019, worked to find the beauty in the sewer. He could build up a density of oil unlike anyone else.His Seated Nude No. 1 (1963) is a swirl of flesh-colored taffy; reproductions cannot do justice to the thickness of its paint-handling. For all of its concreteness, this nude seems to liquefy upon approach into a handful of emotions.

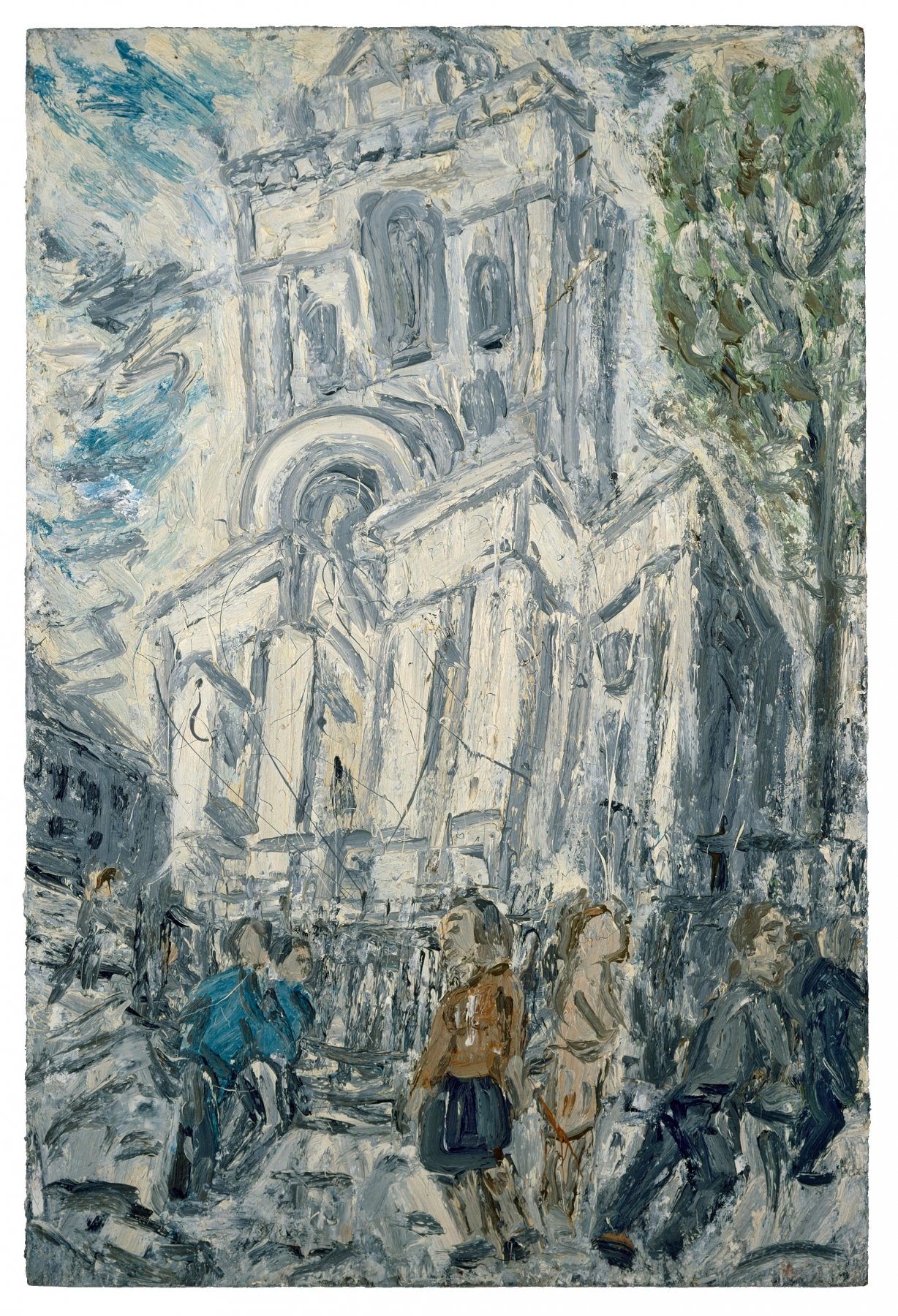

As Kossoff moved from the 1960s into the 1970s and ’80s, he began to dig wider, darker lines back into his wet compositions. The gouges gave his paintings their necessary structure, carving in the details of his portraiture and cityscapes without limiting the freedom of his paint-handling. His two tiny self-portraits here, from 1974 and 1978, look like something you might peel off the bottom of your shoe. Meanwhile Portrait of Rosalind No. 1 (1973) and Father Asleep in Armchair (1978) come across as primitively carved relics painted in relief. As he turned to the urban topography of London’s East End, the roughness of this same approach lent itself to his paintings Demolition of YMCA Building No. 3, Spring (1971), Red Brick School Building, Winter (1982), and Christ Church, Spitalfields, Early Summer (1992).

Leon Kossoff, Christ Church, Spitalfields, Early Summer, 1992 Oil on board, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

This must-see exhibition is timed to the release of the 640-page Leon Kossoff: Catalogue Raisonné of the Oil Paintings by Modern Art Press and is curated by the catalogue’s editor, Andrea Rose. A West Coast version of the exhibition is now on view at California’s L.A. Louver gallery, while London’s Annely Juda Fine Art showed an iteration of the show last fall. Taken together, these initiatives should convince anyone that Kossoff has earned a place in the pantheon of modern art.

Is the School of London having a moment? With “Rodrigo Moynihan: The Studio Paintings, 1970s & 1980s,” David Nolan Gallery gives us a chance to see another artist who kept the oil burning during modernism’s Battle of Britain, when much of the art world had already surrendered to the death of painting.2

Moynihan (1910–90) was a near exact contemporary of Francis Bacon, as John Yau points out in his catalogue essay for the show. “My quarrel is not with the high regard in which Bacon is held,” Yau writes, “but with the fact that Moynihan has not yet been recognized as a major artist. Consisting of self-portraits and still lifes, Moynihan’s late paintings more than hold their own when compared to the work of artists associated with the ‘School of London.’ ”

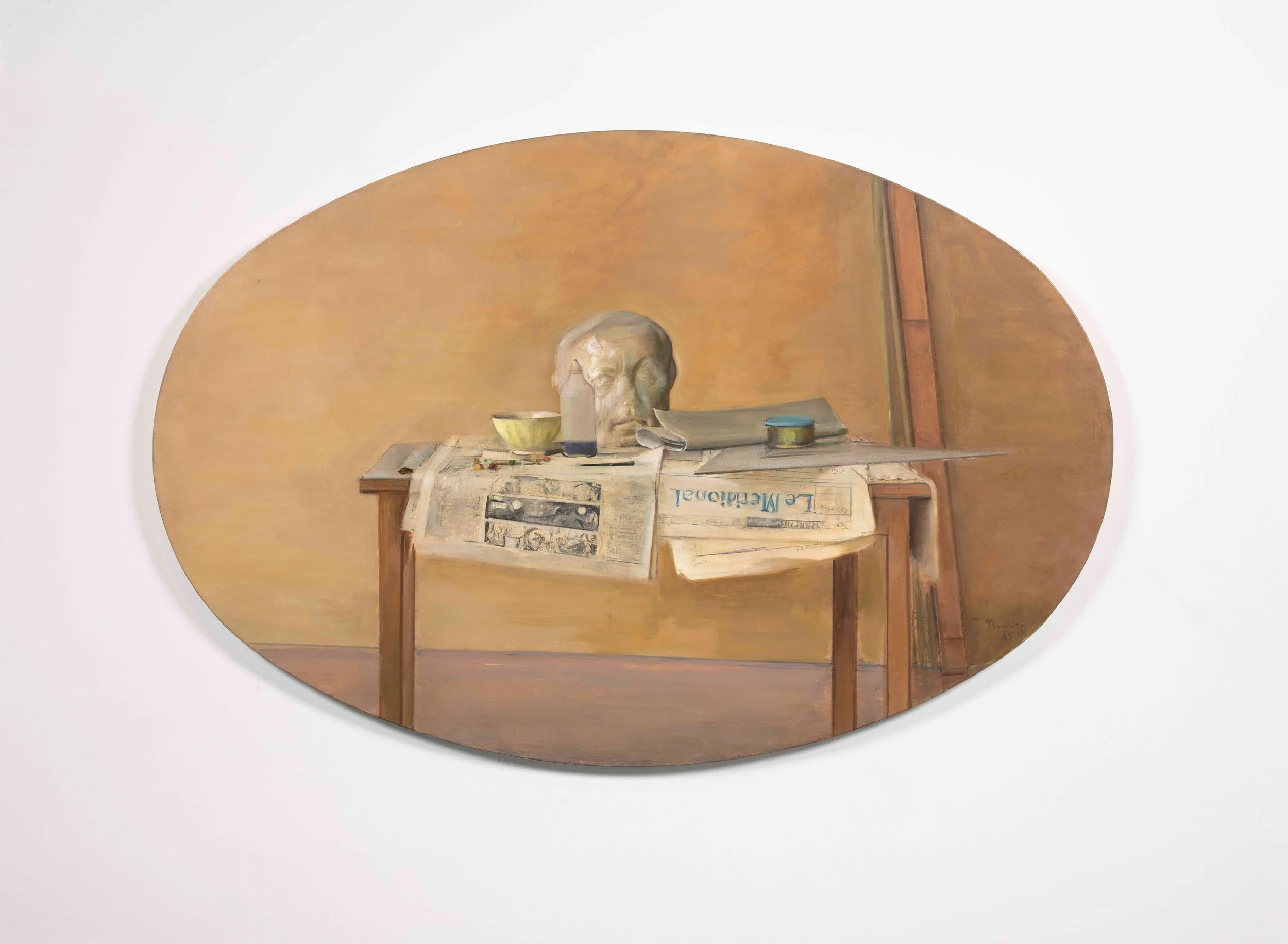

Rodrigo Moynihan, Roman Head on Newspaper, 1986, Oil on canvas. Courtesy of David Nolan Gallery, New York.

Rather than build up his surfaces, Moynihan plumbed the depths of his compositions. Unlike Bacon, however, his paintings were reserved, intimate, and recessional. Frequently he played with scale and framing, producing pictures in pictures. In the case of Summer Interior, his self-portrait from 1981, he depicted himself in a mirror painting a picture (which, though its back is to us, is presumably of said mirror—and the painting we are seeing now). In his still lifes, he observed shelves of objects at unusual angles. “It was especially important to me not to arrange the still life so as to form a pictorial grouping—a picture,” Moynihan said. “I wanted the objects to be found.” Here the arrangement comes from the way he framed these found objects within his canvases. Table legs get cut off, as in Roman Head on Newspaper (1986). Walls nearly evaporate, as in Sponges Near a Window (1973). Often he used round and oval canvases to complicate his compositions further, squaring the circle and circling the square. Corner Shelf (1974) features a small triangular platform hovering in nearly dematerialized space, placed just off-center in a circular frame. A suite of works on paper, of doors ajar and washes of shadow defining depth, shows how he could do much with little. Moynihan was well adept at modulating tone without turning up the volume.

If the classical artist begins with the past, taking lessons from the Old Masters to advance to a modern style, the modern artist might as well go the other way, starting with the present to approach the Old Masters. This has been the case for Paul Resika. The nonagenarian painter began his training with the modern master Hans Hofmann and has been working back through more classical styles in the eight decades since. This month, Resika’s remarkable range, talent, and self-reflection are on wide display with exhibitions spread across two venues.

Paul Resika, Self-Portrait with Rag, 2017, Oil on canvas, Bookstein Projects.

At Bookstein Projects, “Paul Resika: Self-Portraits, 1946–2021” brings together self-portraits he painted between the ages of eighteen and ninety-three.3 From Titian and Tintoretto to Corot and Courbet, the confluence of styles here seems to span the centuries in a time-traveler’s compendium of work. The salon-style hang mixes up the chronology of these self-portraits as well as their artistic influences. The constant is the Zelig-like artist looking back at us through the years with his infectious appetite for the history of painting—both as Renaissance man and modern master.

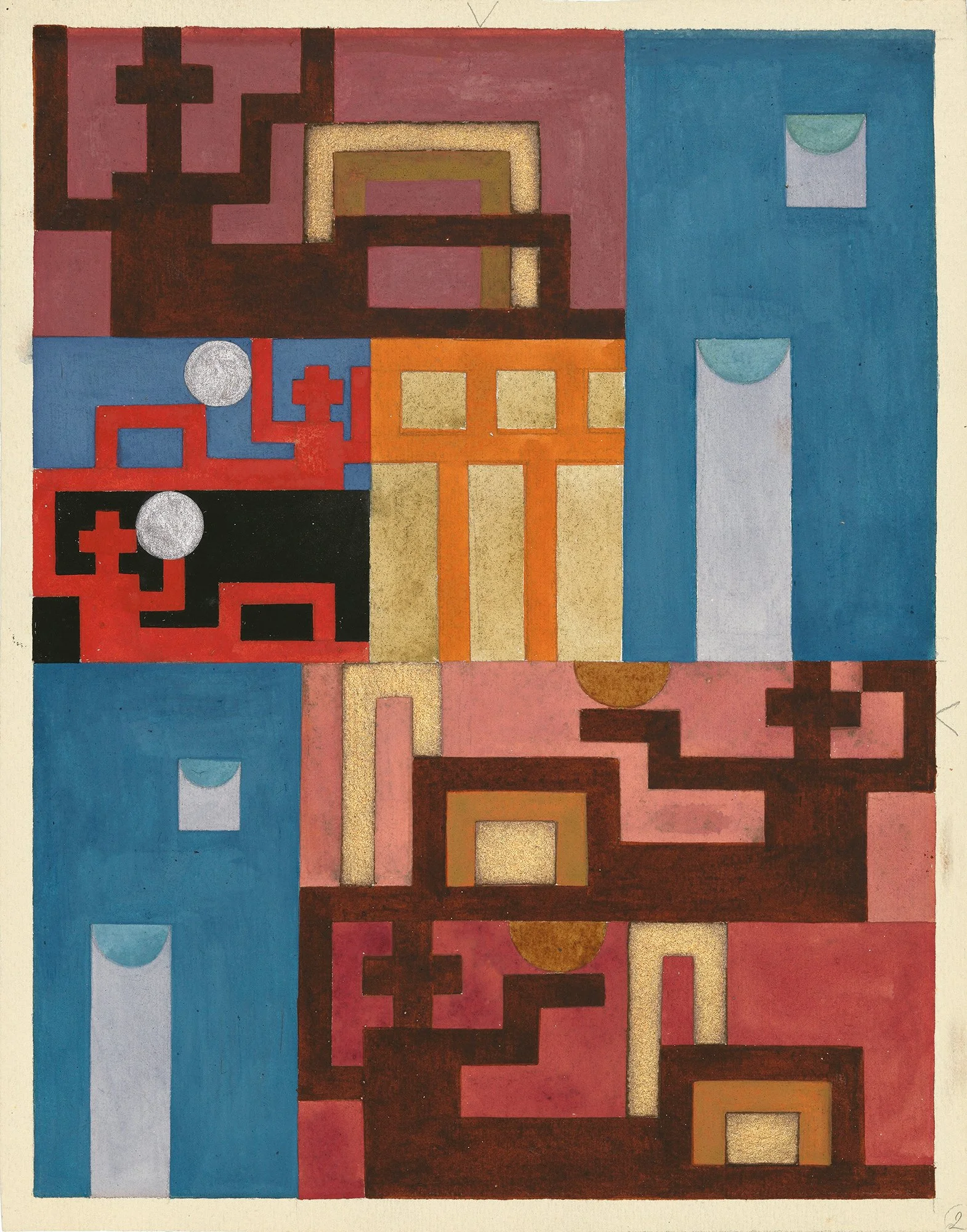

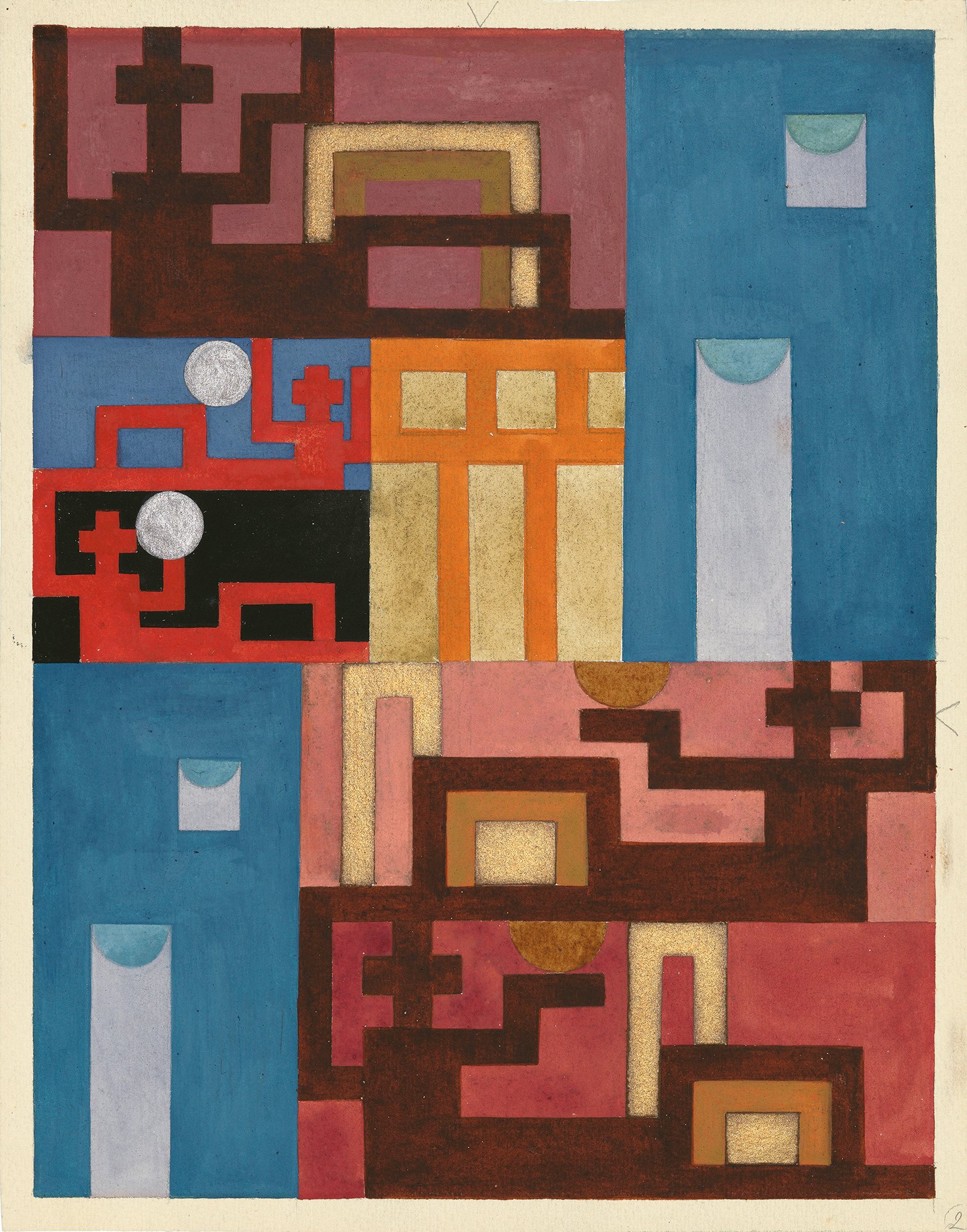

At the gallery of the New York Studio School, “Paul Resika: Allegory (San Nicola di Bari)” presents Resika’s latest work, “derived from an obscure engraving made of a panel from an altarpiece predella (ca. 1437) by Fra Angelico.”4 Attributed to Giuseppe Camilli and Giuseppe Morghen, the small engraving is on loan from Resika’s own collection to be paired with the painter’s lush derivations, which he calls “Allegories.” The place to start, as Resika did, is with the artist’s five small study drawings from 2018. Resika breaks down the composition and figuration of the complex Renaissance scene into pencil outlines. The tiny Study #3 in particular is a delight for its simplicity of forms.

Modernism is an editing down, a distillation and concentration of color and composition. In his own modern paintings Resika draws these spirits out of that “obscure engraving” in remarkable ways. A cliffside town becomes an abstracted wave. An island becomes a sail-like triangle. Sometimes the figures in the foreground disappear completely. In one painting, Allegory (San Nicola di Bari) #9 (2019–21), all that remains is a dark blue rectangle in a light blue field.

Paul Resika, Allegory (San Nicola di Bari) #1, 2018, Oil on canvas, New York Studio School.

These allegories help us see the old engraving and feel its spiritual message in new ways. The patron of sailors and children as well as brewers, archers, pawnbrokers, and repentant thieves, San Nicola was the saint whose miracle was his generosity. His secretive acts of gift-giving evolved into our modern-day tradition of Santa Claus, the jolly old Saint Nick. In his own life, San Nicola redirected a shipment of wheat to feed a starving town. He paid for the dowries of three daughters to rescue them from prostitution. On a trip to the Holy Land he saved a ship by rebuking the waves in a storm. The story of the grain and the salvation at sea are both depicted in Fra Angelico’s painting—the second predella painting of the Perugia Triptych, now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana—and the engraving that came of it. Resika is less interested in copying the details of this engraving than in the miraculous expression it conveys. In these allegories he turns the dials, tunes into this message, and adjusts the frequencies of color and form in his own miraculous ways.

For all of the information it takes in, the work of Rackstraw Downes is more about looking out. The artist’s panoramic vision conveys extraordinary details. Yet his compositions are more about space and our place in it. “I draw, not to establish anything, but to gain acquaintance with a place,” he said in his essay “The Conceptualization of Realism” in 1978. “A drawing, for me, is like a first meeting with a person.”

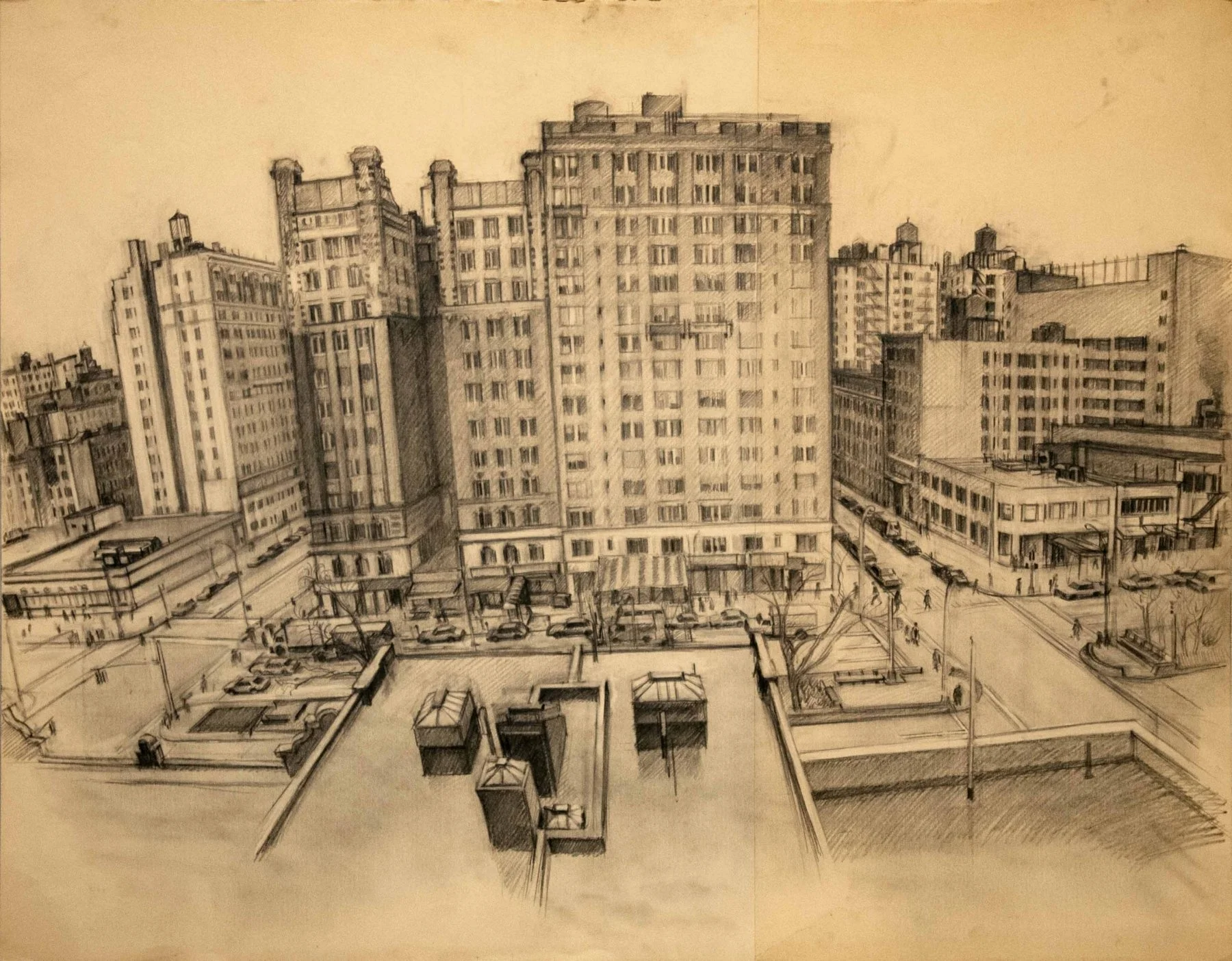

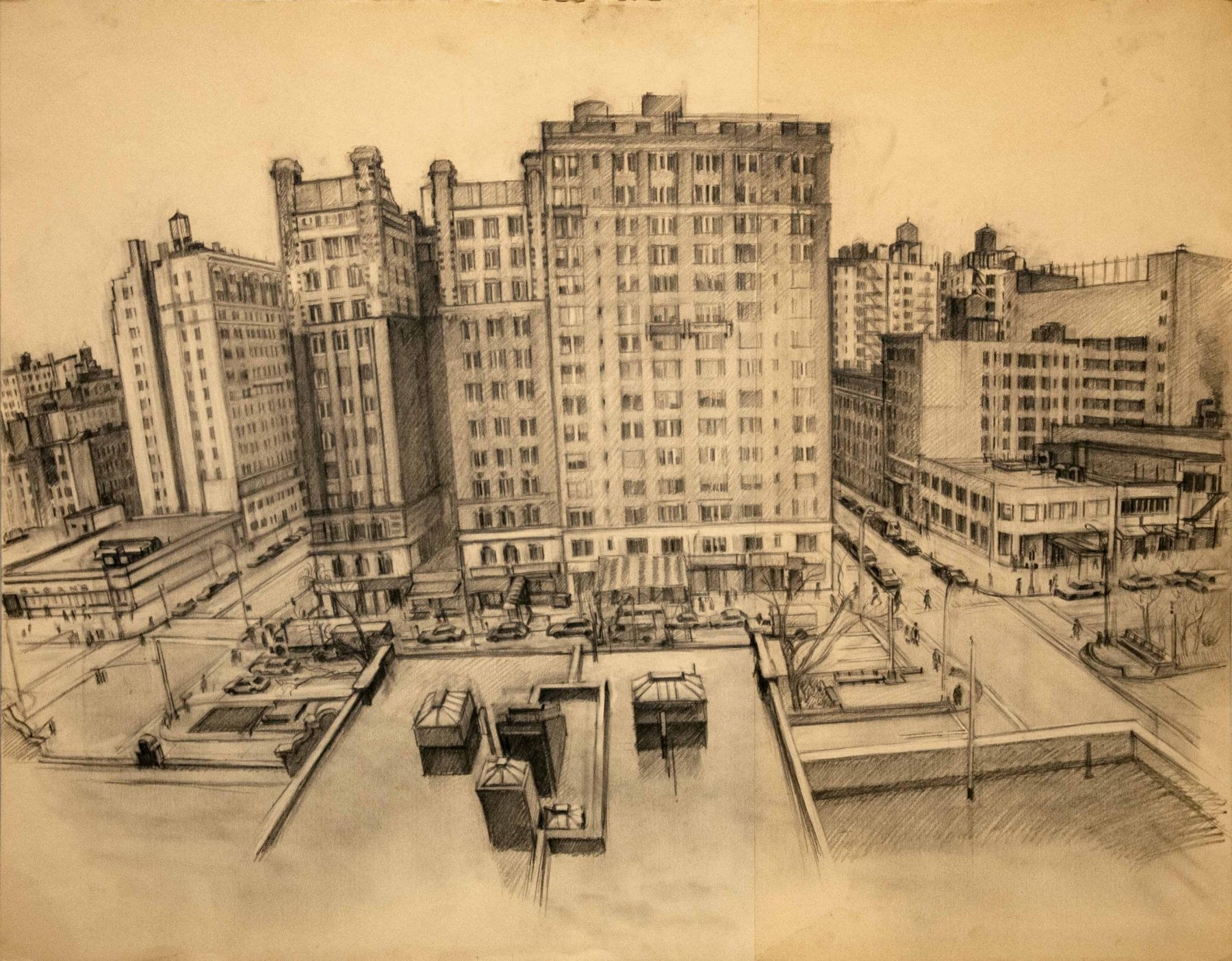

Rackstraw Downes, Looking Down from the Window of a Friend’s on the Upper West Side, ca. 1975, Graphite on manilla paper. Now on view at Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York.

An exhibition of these drawings, pairing compositions from the 1970s and ’80s with current work, is now on view at Betty Cuningham Gallery.5 Composed from direct observation rather than photographs, these drawings amplify our sense for seeing—and feeling—in space. In Looking Down from the Window of a Friend’s on the Upper West Side (ca. 1975), the sight of the apartment windows across the rooflines reminds us of our vertiginous perspective. In Drawing for a Soft Ground Etching: Scaffold Round the South Tower of the St. John the Divine (1984), the scaffold and trees of the cathedral loom over the infinite lines of Amsterdam Avenue on which we stand. In Presidio Cell Tower (2005), the hillside paths and slender tower seem like a landscape in miniature—a diorama in which to wander.

It is said that our mobility affects our sense of space. As Downes’s life turned increasingly inward in 2020, his compositions closed in. Chairs and other props now fill the voids of his studio. Even the air, seemingly so crystal clear in earlier work, becomes thick. As the pandemic has set new limits, these latest drawings by the eighty-two-year-old artist, increasingly housebound in his SoHo loft, convey the stifling sense of a new reality.

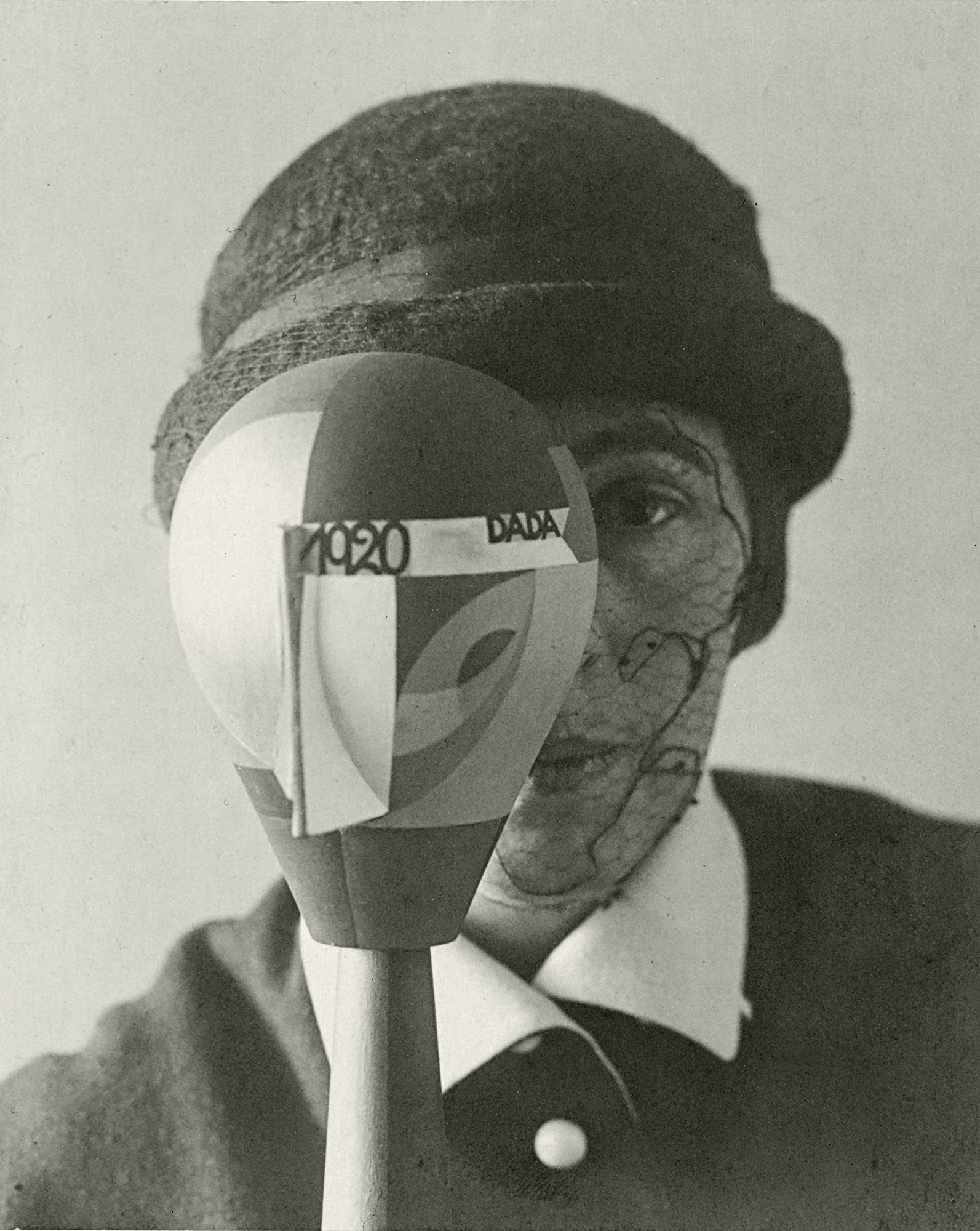

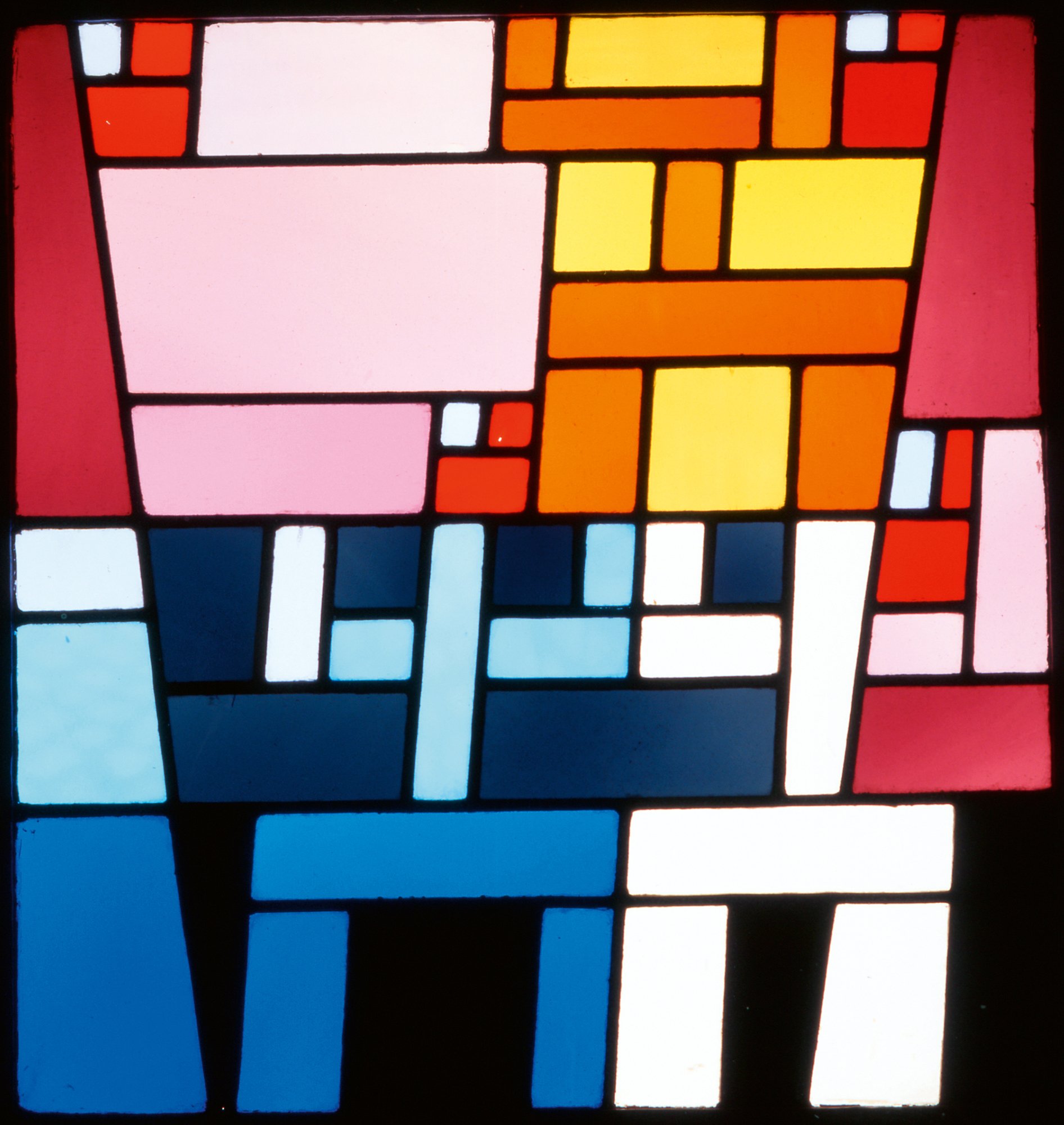

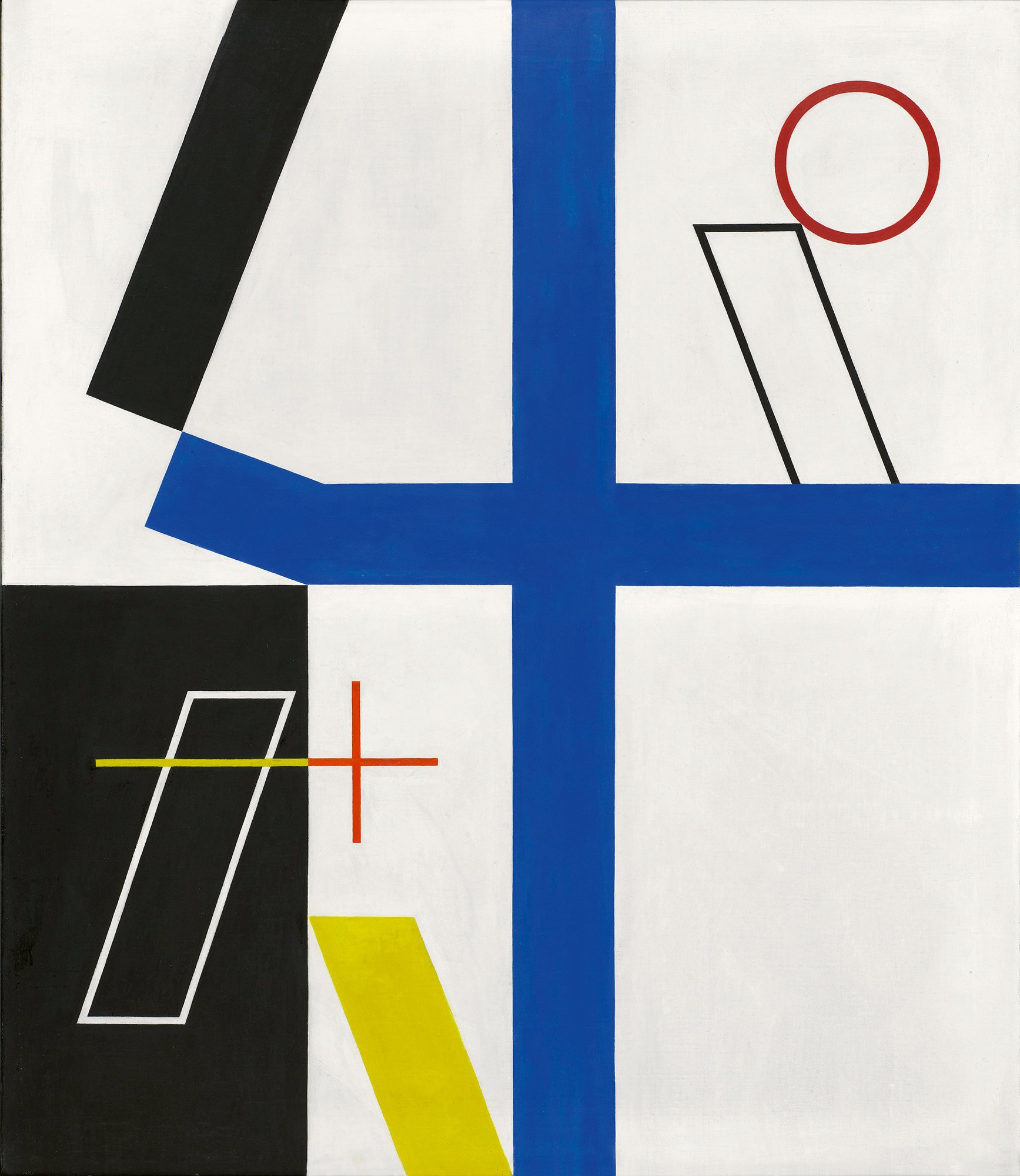

Afinal note about Fred Gutzeit, a painter who died in early January at the age of eighty-two. For over fifty years he drew the ripples of art. A retrospective last fall at Catherine Fosnot Art Gallery and Center in New London, Connecticut, began with Tree, Field, and Minnows, a tranquil reflection on a pond from 1966, and followed his work through increasing reverberations and complexities, ending with abstractions such as Future Life Puzzle (2020). I first wrote about the ripple effect of Gutzeit’s compositions in his “SigNature” series, with its abstracted script refracted through psychedelic patterns, in my “Gallery chronicle” of October 2012.

Fred became a regular correspondent of mine. His interactions felt like they were part of his artistic project—a rippling out of interpersonal feeling. He devised projects to spread art by mail. His generosity also spoke of an independent spirit that reflected the hardscrabble Bowery scene in which he lived and worked. Just before his death, what proved to be his final letter to me suggested we put a show together of Bowery artists—a “democratic” show, he wrote, of “artists who have been citizens of the Bowery.” He shared a print of a Miller High Life can crushed on the pavement, which he called “my most iconic Bowery painting.” The image proved to be a memento mori—a sensibility never far from the Bowery street and Fred Gutzeit’s deep understanding of it.

“Leon Kossoff: A Life in Painting” opened at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, on January 13 and remains on view through March 5, 2022.

“Rodrigo Moynihan: The Studio Paintings, 1970s & 1980s” opened at David Nolan Gallery, New York, on January 20 and remains on view through March 5, 2022.

“Paul Resika: Self-Portraits, 1946–2021” opened at Bookstein Projects, New York, on January 14 and remains on view through March 4, 2022.

“Paul Resika: Allegory (San Nicola di Bari)” opened at the gallery of the New York Studio School on January 31 and remains on view through March 6, 2022.

“Drawings: Rackstraw Downes” opened at Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, on January 27 and remains on view through March 19, 2022.