THE SPECTATOR WORLD EDITION, April 2022

Holbein’s heroes have arrived in New York City

There’s a moment in portraiture when people started having a mind of their own. All of a sudden you see it in the faces: the eyes, the brow, the lip. We are no longer looking at a figure for all time — or even a sitter in a moment in time — but at something more like “me time.” The focus is not on outward appearances but inward looking. These people are lost in thought.

That’s just where Hans Holbein the Younger, the great portraitist of the early sixteenth century, found them. The German artist, born into a family of painters around 1497, could conjure the smallest details at his fingertips. He quickly became the most sought-after portraitist in Europe and, by 1536, the court painter of Henry VIII (at a time when Henry himself was courting).

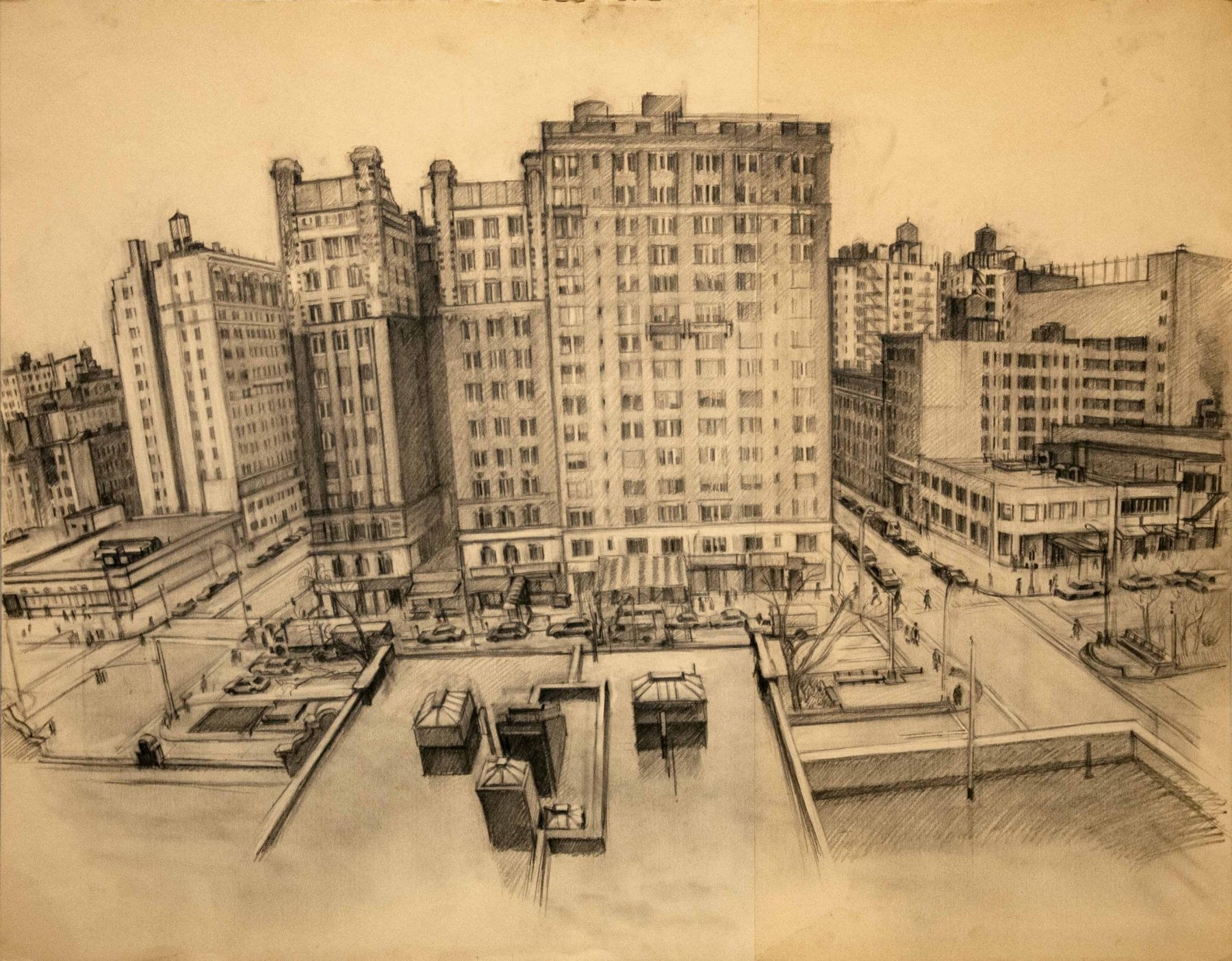

What set Holbein apart was what he saw in his sitters and what he chose not to see. He radically edited down the background of his paintings and removed the trappings of possessions. Instead he captured his sitters, simply put, capturing themselves. Holbein: Capturing Character, an exhibition gathered from twenty lenders of more than thirty paintings and drawings by Holbein, as well as paintings, books and jewelry by his contemporaries, is now on view at New York’s Morgan Library & Museum.

Europe of the early 1500s was having a moment of its own. Technological revolutions, after all, can be even more life-altering than political revolutions. If you think today’s digital revolution has been something, consider the Gutenberg revolution of the later fifteenth century. While Johannes Gutenberg’s Bible came out in 1450, the German metalsmith from Mainz remained largely unknown in his lifetime. He died a financial failure. But his invention of movable type sent shockwaves through much of Europe. Thirty years after his Bible’s first revelatory run, there were 110 printing presses across Europe. Fifty of them were in Venice alone. By 1500, European presses had already produced over twenty million books.

All of a sudden, literature became personal. A new bumper crop of classics in translation brought the wisdom of antiquity to a wider public. Scholasticism and the oral tradition gave way to more direct intellectual engagement. Rather than scribes copying manuscripts generation after generation, book printing made authorship instantaneous and individual. The act of reading also became silent. At the same time, contemporary writers became the world’s first bestsellers as they overturned Europe’s religious and cultural order. Luther distributed 300,000 of his printed tracts. Meanwhile the humanist Erasmus — something of a centrist in a schismatic age — sold 750,000 copies of his books.

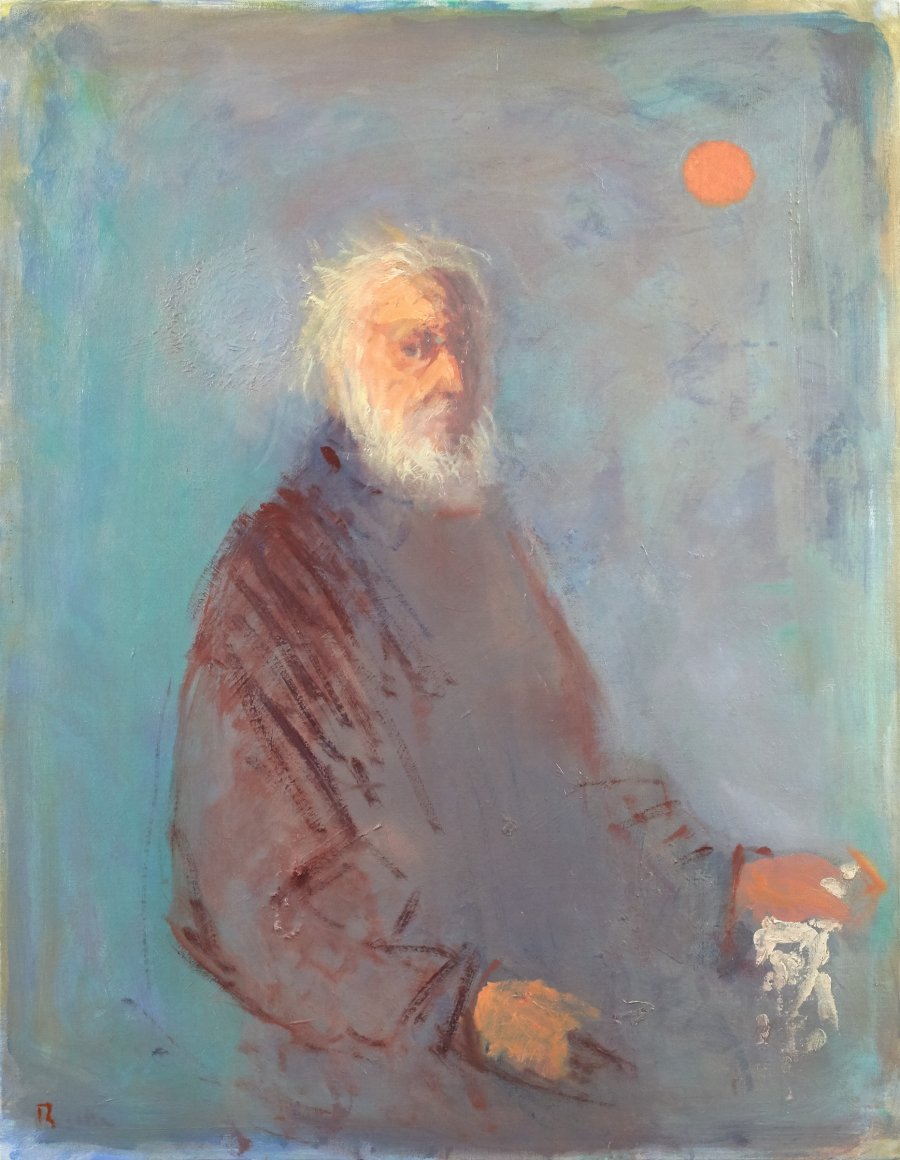

A former priest who popularized philosophy and attacked modern superstitions, Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam was the Jordan Peterson of his day — at least when it came to his reach and popularity. He was the “prince of the Humanists” for his book In Praise of Folly, written while he was visiting the English statesman Thomas More. He was also a champion of Holbein and sat for several portraits, both large and small, throughout his later life. It was Erasmus who introduced Holbein to More and the inner circle of the English crown. Whenever you think of Henry VIII looking like the King of Hearts, with his head a quarter turned in playing-card profile, recall that it was Holbein who painted that original portrait.

There is no Stout Harry at the Morgan, but Holbein’s More is here, the 1527 painting lent by the Frick Collection as the 70th Street museum undergoes a lamentable “renovation.” Removed from its Frick pairing with Holbein’s portrait of Thomas Cromwell, More now strikes us as, well, even a bit more. The painting is now hung close to eye level. You can just about make out every stubble of More’s five-o’clock shadow. With a mixture of focus and fatigue, England’s future Lord High Chancellor stares over our shoulder into space. A wrinkle of his furrowed brow connects between his eyes on the bridge of his nose. At its corner, his lip turns down in the hint of a frown. A luminous green curtain hangs behind him.

A humanist philosopher, More argued against the reformation of Martin Luther and John Calvin. When it came to acknowledging Henry’s own claim to be the supreme head of the Church of England after the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, More also dissented. “I die the King’s good servant, and God’s first,” More said as he was executed for treason just five years after sitting for Holbein’s portrait.

You can already see the weight of history in More’s world-weary face. His expression contrasts with his sumptuous fur collar and the red-velvet sleeves of his doublet shimmering in the light. Holbein rendered the S-shaped links of his gold livery chain, a symbol of More’s royal service, with a jeweler’s detail. Originally trained in miniature, Holbein could decorate his portraits as though he were adorning their very surfaces with precious metalwork. (For those who caught Capturing Character at the Getty Museum, where this exhibition curated by Anne T. Woollett originated, it was the portrait of Cromwell, More’s rival, that got the all-expenses-paid trip from the Frick to Los Angeles.)

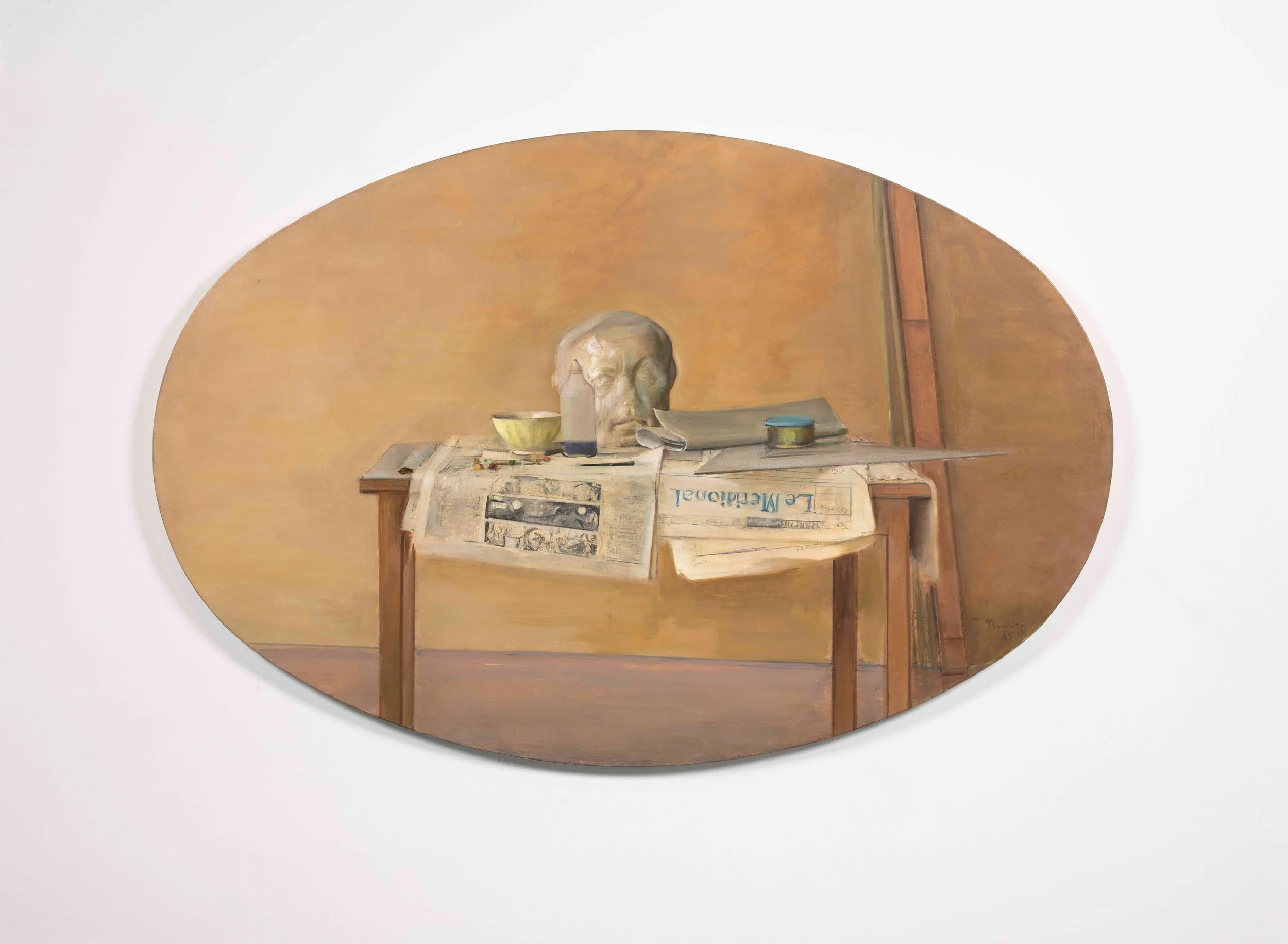

Be sure to bring your reading glasses when visiting the Morgan. There is an abundance of small detail here that calls out for close looking: roundel portraits, rings and coins, even a tiny portable portrait still with its original lid. Holbein could add just the right evocative detail, especially to his sensuous portraits of women. Books are never far from the mind in this exhibition. Holbein designed a suite of tiny woodcuts for a book on “The Dance of Death” (c. 1526, published 1538) — a memento mori of dancing skeletons. Figures are also shown reading, or writing, or at the very least holding the book that was occupying their attention until we walked in the room. “Mary, Lady Guildford” (1527) looks like she is about to whack us over the head with the small hardcover now clasped closed in her hands.

Books are not unique to Holbein’s paintings. We can see them in the work of contemporaries exhibited alongside him: Albrecht Dürer, Quentin Matsys and Jan Gossaert. But unlike these windows on the world, all packed with details and distractions, Holbein’s portraits reflect a more direct literary experience — of that inner voice, not just speaking, but reading and dictating thoughts in our heads.

Sometimes these words illuminated the very portraits themselves. “The year 1533, at the age of 39” (ANNO 1533 AETATIS SVAE 39) reads the gold lettering seemingly tooled right into the surface of Holbein’s “A Member of the Wedigh Family.” Or how about the sign tacked to the tree on the portrait of “Bonifacius Amerbach” of 1519: “I am not inferior to the living face; I am instead the counterpart of my master, and distinguished by accurate lines. Just as he completes three intervals each lasting eight years, this work of art diligently renders his true character.” Below, the sign reads: “Jo[hannes] Holbein painting Bon[ifacius] Amerbach on 14 October 1519.”

In other words, Holbein is the painter of the portrait. The young man depicted is the author and master of the twenty-four-year- old life therein. For those sitting for a portrait by Holbein in the turbulent early years of the sixteenth century, it must have seemed like they were all the authors of their fates, probably more than ever before. Henry VIII certainly thought so, as did Erasmus. In the thoughtful depth of his arresting portraits, Holbein painted the dust-jacket images for all their books of life.