Brewster Kahle, founder of the Internet Archive (all photographs by the author for Hyperallergic)

HYPERALLERGIC

December 4, 2013

At the Internet Archive, Saving Data While Spurning the Cloud

by James Panero

SAN FRANCISCO — At 3:30 am on November 6, a fire swept through the scanning center of the Internet Archive. The news was poignant for an organization that thinks hard about how information is lost and the best ways to save it. For nearly two decades, the San Francisco nonprofit has been uniquely dedicated to the open preservation of web, text, coding, audio, and video media — a Library of Congress for the 21st century built through private philanthropy and sweat equity. None of the Archive’s employees or volunteers were hurt in the blaze, but the fire totaled the Archive’s annex building along with $600,000 in digitization equipment and some irreplaceable archival material. An emergency appeal brought in $60,000 over its first two days, and the drive is ongoing.

“This episode has reminded us that digitizing and making copies are good strategies for both access and preservation,” wrote Brewster Kahle, the Archive’s founder and director, on the organization’s blog the day of the fire. Thanks to the Archive’s mirrored servers — spread over three continents — and a warehouse of hard-copy source material, Kahle said the Archive’s digital data would have survived even if its headquarters had been fully destroyed. “Let's keep making copies,” he concluded. (The virtue of the Internet’s duplicating qualities is a topic I wrote about in an essay called “The Culture of the Copy.”)

How libraries endure was on Kahle’s mind when I visited the Archive in San Francisco’s Richmond District earlier this year. “What happens to libraries is that they’re burned,” he said. “They are generally burned by governments. The Library of Congress, for instance, has already been burned once, by the Brits. So if that’s what happens, well, design for it, make copies.”

Internet Archive servers in the Christian Science building that houses the organization in San Francisco

Kahle now has the resources to make copies on a grand scale. The Archive recently surpassed 10 petabytes of data (they printed bumpers stickers to mark the milestone). The nonprofit costs $12 million a year to run: about $5 million of that comes in from libraries paying 10 cents a page for digital scans, $2 million comes from national and local libraries paying for archival services, and about $5 million comes in from foundations. “I am the funder of last resort,” says Kahle. “I won the lottery, the Internet lottery, so I can plug in when it doesn’t come through.” Even before Kahle sold his company Alexa Internet to Amazon in the late 1990s, he had focused on preserving digital information through duplication. “If the Library of Alexandria had made copies, and put them into either India or China, we would have the other works of Aristotle, the other plays of Euripides.”

A “scribe” works at one of the book digitization stations damaged in the fire

In 2009, Kahle moved the Archive headquarters into a former Christian Science church where it operates today. The collonaded facade of the classical building suited Kahle’s Alexandrian aspirations (the Archive has also partnered with the revived Bibliotheca in Alexandria, Egypt). “We bought this building because it matched our logo,” he told me. The basement meeting room became the Archive’s open-plan office, halfway between a tech hub and a student commons. Over a long table where Kahle invited me to join the Archive’s Friday lunch, the office breaks bread with whomever Kahle finds interesting. On the day I visited, Kahle introduced himself by dropping a black box in my hands — an inexpensive hard drive that could store a library’s worth of books and be widely distributed. My other seatmate was a crunchy bookseller from a San Francisco commune.

Upstairs, the church’s large sanctuary remains unchanged save for a few modifications. In the pews are statues of the Archive’s longterm workers. “It’s kind of a riff on the terracotta soldiers idea,” Kahle explained. “If you work at a non-profit there is no gold at the end of the rainbow. There’s no stock options. So this is sort of a way of saying thanks.” In front, the hymnal numbers have been replaced by the numbers for Pi and Phi. In two apses at the back are racks of blinking servers. “That is 2.5 petabytes of the primary copy of the Internet Archive.” Upstairs, in the church’s old offices, are the Archive’s additional primary servers. “The idea of having your data in an off-site location center, or in the ‘cloud,’ wherever the hell that is, strikes me as an insane idea. If it’s really important to you, keep it close to you.” Kahle said the Archive follows its own server design. “To buy something from Dell, HP, Sun, whatever — their profit margins are so unbelievably huge and their products so bad that it actually was better to design and build our own.”

Statues of long-time Internet Archive staffers recall terracotta soldiers

Mixed in among the servers is the Archive’s one-room schoolhouse for Kahle’s teenage son, Logan. “This is a classroom for one student and one teacher,” Kahle said as we walked by. “We are experimenting with one-on-one teaching. Logan wanted to learn differently and faster than what he was able to do in private school.” Kahle argued that his stripped down approach is economically more efficient than a private school with its administration and overhead costs.

For someone who made his fortune off the Internet, Kahle has an unexpected off-the-grid mindset. His sense for multimedia survivalism took off when he realized the technology existed to do what might sound impossible: through the right software and storage, to take a snapshot of the entire open Internet every two months. The public face of this effort became “the Wayback Machine,” the free online interface that allows anyone to search the Archive’s database that at last count boasted “368 Billion web pages saved over time.” What Kahle calls “an out-of-print web pages service” is now used by about 600,000 people a day and is the Archive’s most recognizable feature.

Yet the Archive’s reach now goes beyond the web to the preservation of a broad range of media. “We started collecting television,” Kahle said. “The Library of Congress is supposed to, but they weren’t. Twenty channels of television 24 hours a day.” Last year, the archive created a searchable video database of television news. “We’d like to make everyone into a Jon Stewart research department, so you can basically reference and compare and contrast what it is that has been on television.”

A film digitization station.

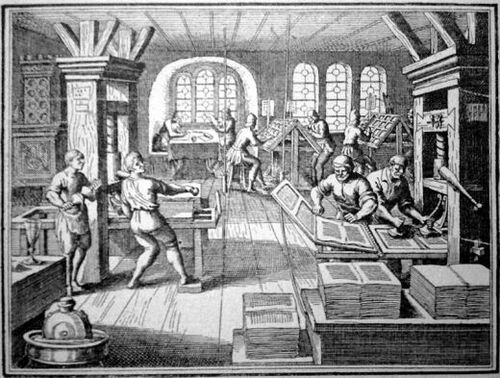

The digital Archive includes recorded audio (with nearly 9,000 live concert recordings of the Grateful Dead), vintage software and gaming code, old public service messages and video captures of ghostly home movies, and a vast library of scanned books, which can either be digitally loaned or downloaded depending on copyright. Here Kahle wants to create an archive similar to Google Books but “without having centralized control.” While he has praised the recent fair use summary judgement in favor of Google Books over The Authors Guild, Kahle has been critical of Google’s proprietorial control over its own scanned archive, as well as the quality that results from its robotic scanners. “We actively encourage people like Aaron Swartz to go and download millions of books at a time,” he says of his own scans. “We publish tools on how to do it. This is what libraries are for.” It was the book and video scanning building, where I saw young employees and volunteers hunched over rows of stations labeled “scribes,” that burned on November 6.

For all his faith in digital technology, Kahle believes in keeping hard copies. While other libraries may scan their contents in order to reduce their paper storage costs, sometimes “de-accessioning” books to pulping mills, Kahle has created an offsite storage vault where he hopes to keep a copy of every published book available, which he estimates to be 10 million copies. Much like the Svalbard Global Seed Vault buried in the permafrost of Norway, what he calls “The Physical Archive of the Internet Archive” already stores 500,000 copies in climate-controlled shipping containers along with other hard copy assets such as the Archive’s old servers — all there for future needs or an archive of last resort in a doomday destruction of the digital database.

“I have more faith right now in the Wikipedia generation than I do in the institutions that get all the funding, whether they be universities, libraries, museums. The bottom up generation is building the real infrastructure,” Kahle said.

“So how come you’re not the Librarian of Congress?” I asked.

“He’s still alive,” Kahle responded, as he moved on to point out the next rack of servers.