THE NEW CRITERION, May 2021

On the un-zooing of the zoo

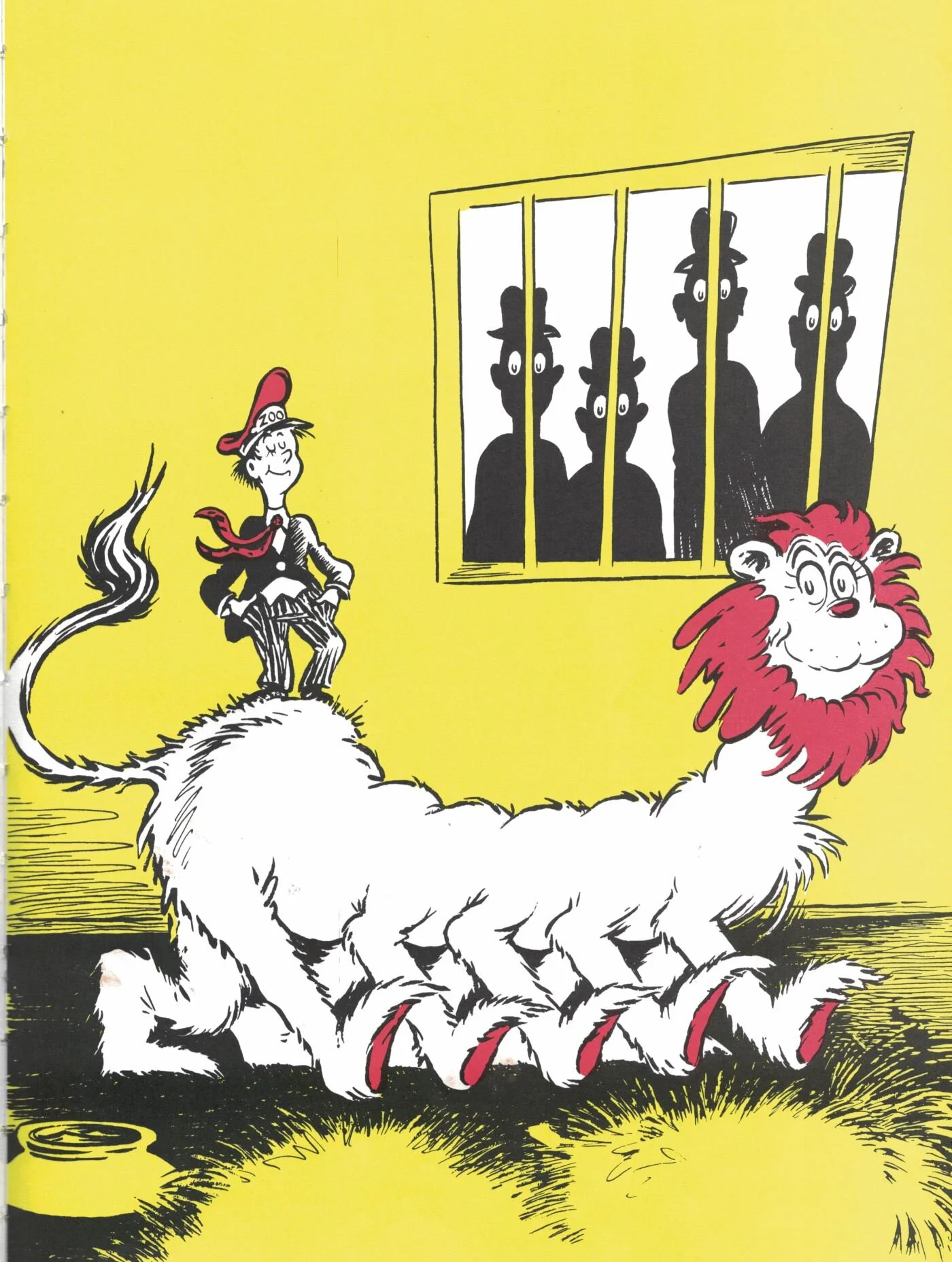

What is so wild about If I Ran the Zoo? Don’t ask young Gerald McGrew. It was hard to escape the news when, on March 2, the zoo-loving protagonist of Dr. Seuss’s 1950 children’s book was captured and caged along with five other titles. The author’s own estate threw away the key to what quickly became the endangered species of its archive. The confinement not only ended the publication and licensing of six books. The move also cut into our ability to buy used copies of the books online. eBay announced it was “sweeping our marketplace” to remove these titles that now violated the company’s “offensive material policy.” The street price for ragged copies shot up a hundred fold. Overnight, Mein Kampf became more available than the anapestic tetrameters of that “New Zoo, McGrew Zoo.”

Somewhere between “Pasternak, Boris” and “Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr,” “Seuss, Dr.” might seem like an unexpected addition to the samizdat library. Yet some have long looked to cancel the writer beloved by generations for hitting the funny bones of children while twisting the tongues of parents. This year for “Read Across America Day,” the National Education Association declined to acknowledge Seuss at its annual March event that is, in fact, timed to coincide with the author’s birthday (Seuss had been the focus of the event during both the Obama and Trump administrations). Faced with the full loss of its intellectual property’s value, “working with a panel of experts, including educators,” Seuss Enterprises instead used the birthday to announce that six Seuss books were the first things to go—like stockings hung all in a row.

Born in 1904, Theodor Seuss Geisel had the misfortune of beginning his career as a college humorist at a time when nothing was funny, at least by today’s standards. Some of Seuss’s sophomoric efforts were indeed cringe-making by anyone’s standards. As his early work has been unearthed, activists have painted Seuss as an unregenerate racist who encoded hate into everything from The Cat in the Hat’s supposed minstrelry to Horton’s unwanted paternalism in hearing that Who.

The indictment of If I Ran the Zoo speaks not only to a modern problem with Seuss but also to a modern problem with zoos. Katie Ishizuka and Ramón Stephens are the married academics behind an organization called The Conscious Kid that has led the prosecution against the book. With over two million followers, their Instagram account is the kind that promises to reveal “Childhood nursery rhymes you didn’t realize were racist.” In their 2019 study called The Cat Is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, Anti-Blackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss’s Children’s Books, the two make a diversity audit of Seuss and particularly target If I Ran the Zoo.

By scouring the world, or at least the world of his dreams, for unusual animals “to be put on display in the White male’s zoo,” according to the authors of the study, Gerald McGrew traffics in Orientalism, subservience, “exotification, stereotypes, and dominance”:

In addition to White males dominating the presence and speaking roles of characters, their violence is used as a tool of White masculinity to support dominance and White supremacy over additional forms of masculinity. An example of how White supremacy, specifically White masculinity, uses violence to support dominance is mentioned in the findings where we see a White male holding a gun while standing on top of the heads of three Asian men.

It is true that McGrew enlists “helpers who all wear their eyes at a slant” from “countries no one can spell.” He also goes “to the African island of Yerka” and employs local aid to return with a “tizzle-topped Tufted Mazurka.” Yet the study’s authors conveniently ignore that McGrew’s exoticizing gaze was an equal opportunity offender, extending to the “Far Western part of south-east North Dakota,” where one can find a “very fine animal called the Iota.” McGrew also tasks local blue bloods in the “Wilds of Nantucket” to “capture a family of Lunks in a bucket.”

For some, the history of America’s zoological parks is not so unlike the one imagined by young Gerald McGrew—and just as damning. For those who run today’s zoos, their cultural position may be just as tenuous as the publication of If I Ran the Zoo. As far back as 1985, Dale Jamieson was writing “Against Zoos” for a chapter in Peter Singer’s In Defense of Animals. In 2018, a group called the The Non-human Rights Project sued the Bronx Zoo, New York’s flagship zoological institution, demanding legal personhood for Happy, the elephant who has lived “wrongfully imprisoned” at the zoo, the suit maintained, for forty-two years. While a Bronx County Supreme Court judge ruled against the motion in February, the zoo nonetheless announced it would soon end its elephant exhibit.

The un-zooing of the zoo should come as no surprise. Since 1993, the Bronx Zoo has officially not been known as a zoo at all, but the “Wildlife Conservation Society.” At the time of the renaming, zoo guides complained that they must now be known as stuffy “docents” in a “wildlife conservation center.” “The society is no longer simply a keeper of zoos and an aquarium, wonderful though those facilities may be,” responded trustee John Elliott, Jr. “The society’s primary mission is to save wildlife. Its new name reflects that mission. Fair enough?”

While the Bronx Zoo has, unofficially at least, now consented to calling itself the Bronx Zoo, a conservation mantra continues to permeate its exhibits. Animals, when they can be seen, are often woefully under-identified, appearing as mere props for a presentation on the dangers of pollution, or deforestation, or some other man-made calamity. At the conclusion of many exhibits, we are given opportunities to atone for our own culpability in this Malthusian world through the contribution of funds.

The zoo’s mission creep reflects a growing discomfort over the dynamics of its founding, a time when elite (and, yes, white) collectors indeed filled cages with game nearly as exotic and far-flung as those specimens for McGrew’s zoo. At the Bronx Zoo, the animals are now dispersed across the park, but what remains of its turn-of-the-century art and architecture, often overlooked by visitors, still speaks to the zoo’s original ambitions.

The New York Zoological Park, as the Bronx Zoo was originally known, began as an initiative of the Boone and Crockett Club, an association founded in 1887 by ten wealthy big-game hunters, including Theodore Roosevelt. Dedicated to game protection and game preserves, in 1895 the Club seeded the board of a new zoological society that would establish a free park “with North American and exotic animals, for the benefit and enjoyment of the general public, the zoologist, the sportsman and every lover of nature,” the Society wrote in its first annual report of 1897. Andrew Carnegie, Cornelius Vanderbilt II, Jacob Schiff, and William C. Whitney were among the first donors as the society took control of 261 acres, an ambitiously large tract of undeveloped land straddling the Bronx River that had been acquired by the New York City Municipal Park Commission in 1884.

These days visitors mainly arrive at the zoo by some back door, as parking lots disgorge them unceremoniously in some odd corner of the park. Yet as conceived, the zoo presented an ordered and elevating classical assembly leading visitors up to nothing less than an acropolis for the animal kingdom. To get some sense of that, today’s visitors must start at the zoo’s original entrance along East Fordham Road, at one time an arboreal boulevard serviced by nearby elevated rail and separating the zoo from the New York Botanical Garden to the north.

Here one of the last monuments of the zoo’s classical period still anticipates the animal wonders within. In 1934, the zoo unveiled the double-arched bronze gates as a memorial to Paul J. Rainey. His sister, Grace Rainey Rogers, commissioned the sculptor Paul Manship to create the fanciful design based on actual animals in the zoo’s collection. Tortoises, cranes, storks, owls, bears, deer, baboons, leopards, and a lion named Sultan perch on the gate’s stylized vines. The menagerie pays tribute to Rainey, the big-game hunter who filled the zoo, as well as nature museums, with the gifts of his exotic specimens. His 1911 report of his arctic adventure to capture “Silver King,” one of the zoo’s first polar bears, reads like a cross between If I Ran the Zoo and King Kong. As Rainey recounts, after much struggle the first bear he roped on an iceberg was mistakenly garroted: “Presently it seemed to me that the bear was choking, and I ordered the rope loosened at once. Too late! His eyes were glassy, and he was stone dead.”

Past the Memorial Gates, the original zoo entrance leads onto a fountain plaza and set of monumental steps that were at one time bursting with floral arrangements, now mainly turned over to parking and denuded lawn. Here the Rockefeller Fountain, of imagined sea creatures, still adds to the stairs’ Italianate design with its unusual provenance: originally from Como, Italy, where it was created by the local sculptor Biagio Catella in 1872, the fountain was purchased by William Rockefeller as a gift for the zoo in 1902.

Up the stairs, the zoo’s Astor Court, originally known as Baird Court, still speaks to the zoo’s original focus, in mineral if no longer in animal or vegetable form. Designed by the architects Heins & La Farge, the Court’s brick and limestone neoclassical buildings once housed the animals at the heart of the zoo. Modeled after the Court of Honor at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago of 1893, Astor Court is symmetrical and longitudinal, with the Primates’ House, Lion House, and Large Bird House leading on to the domed Elephant House. Stone and terracotta animal sculptures by Eli Harvey, Charles R. Knight, and Alexander Phimister Proctor cover the façades as though the buildings have been given over to the natural world. Of this design, only the central sea lion pool still serves its original function. While the Court buildings have been restored and maintained through a gift of the Astor family, they are otherwise closed to the public or greatly altered. The Elephant House now houses the museum’s rhinoceri, while the cages of the Lion House have been removed to create an immersive exhibition called “Madagascar!” Lions, primates, birds, and elephants (for now) appear elsewhere, removed into sprawling and often distant settings.

The Elephant House at the Bronx Zoo. Photo: WCS Archives.

These naturalistic habitats, most likely more salubrious for the animals’ captivity, may be in line with updated zoological practice, but something got lost in the transition. The animals at the zoo are not in a state of nature, despite the artifice of their current surroundings. With their ordered arrangement, the animals as presented in the neoclassical Astor Court were more clearly and honestly in a state of man. The animal heads sculpted onto these buildings at one time even reflected the actual assembly of the National Collection of Heads and Horns, prize trophies that originally occupied a sixth Court building, designed by Henry D. Whitfield in 1922.

From McGrew Zoo to Bronx Zoo, zoological parks as originally conceived served to reveal not white supremacy but human supremacy, and therefore human responsibility, over the animal kingdom. The big-game hunters who founded the Bronx Zoo maintained such a deep respect for animal behavior and animal habitat that they created this shrine to animals. In the modern age, the animals of the world are the captives of man with no chance of release. Let’s at least give us unwitting jailers a direct engagement with the wonders of creation in our charge. If I ran the zoo, that’s just what I’d do.