THE NEW CRITERION, October 2023

On Greek colonies, Etruscan tombs & Italian origins.

The landing began eighty years ago at one minute past midnight. Loudspeakers on the American troopships approaching the coast of Italy gave the signal. In the first moments of September 9, 1943—an earlier D-Day of the Second World War, this one of Operation Avalanche—soldiers climbed over the gunwales and down the nets into their landing crafts. Their destination was the fortified beach at Paestum, a town in Campania along the sandy coast twenty-five miles south of Salerno.

Italy had surrendered to the Allies just a day before, but Nazi forces were dug in. The amphibious assault around the ankle of Italy was meant to free the boot of what was now German-occupied territory. Paestum was to serve as one of the beachheads for the American and British campaign north and west up the peninsula while isolating German troops to the south. By enabling the eventual capture of Naples and then Rome and beyond, the landing was another step in the liberation of Italy and the slow march on Germany; Operation Overlord and the Allied landing at Normandy were still nine months off.

At H-Hour—three-thirty in the morning—the landing crafts, or those that were able to find their way in the night, came together three miles out to sea. They then made their final approach towards the dark beach.

“Come on in and give up!” a German voice blared from loudspeakers on shore. “We have you covered.”

To achieve the element of surprise, the American generals had decided not to bomb the Tyrrhenian coastline leading up to the landing. A British diversionary assault then tried to draw German forces out of the area. The deceptions proved counterproductive. The waters were mined. The Paestum beach was defended with gun emplacements and wire. Eight divisions from the German Tenth Army, under the command of Heinrich von Vietinghoff, were stationed to counter the American assault. Against artillery, aerial, sniper, and machine gunfire, and a counterattack from the Sixteenth Panzer Division that nearly pushed them back into the sea, American forces stormed the beaches and fought to reach assembly points inland.

Photograph: Photographer unknown, National Archives, Washington D.C.

As supplies and personnel began moving in from the beachheads, a Negro unit from Headquarters Company, 480th Port Battalion, established a temporary office in the ruins of a Greek temple just off the beach. These U.S. signal-corps soldiers unloaded their portable equipment and began their relay work among the ruins of what we now call the Temple of Hera II. They sat on wooden crates and rested their helmets and canteens atop their fold-out desks and typewriter boxes.

On September 22, an army photographer came upon their bivouac and recorded their field office. “A company of men has set up its office between the columns (Doric) of an ancient Greek temple of Neptune, built about 700 B.C.,” reads the caption on photograph 111-SC-181588, now in the National Archives. As the signal officers worked in a line at their makeshift desks on the temple platform, the scene of ancient and modern, of new arrivals communing with settled stones, became one of the more iconic photographs of the Second World War. Here were segregated American soldiers fighting the German Wehr-macht from a Greek temple on Italian soil. The uncanny confluence served as a reminder that the Apennine Peninsula has long been contested by waves of warring nations. There was even an Italy before Rome.

Twenty-five hundred years before, in this low tidal area near the mouth of the Sele River, ancient Greek mariners had created their own Italian beachhead at the same spot. They called their outpost Poseidonia, after the ocean god Poseidon. They carved out streets and houses and built a row of temples out of the local iron-rich stone, which, unlike their native Greek marble, turned red in the salt air.

Human settlement here dates back to the Stone Age. The nearby rivers, fed by steep mountains to the east, produce a fertile floodplain. The Greek colony was founded in the mid-seventh century B.C., one in that constellation of Hellenic settlements the Romans later called Magna Graecia. But this was still some fifty years before the village of Rome—then just a small settlement clinging to a handful of rises above the Tiber River—has drained the land for its Forum between the Capitoline and Palatine Hills.

At the time, the Etruscans, competitors and occasional overlords of the Latin tribes, were gaining power in the area. This Greek outpost, like the American beachhead, was intended to forestall enemy expansion and protect friendly settlements to the south. Over the next few hundred years after its founding, the town fell to the Italic Lucanians, then returned to the Greeks, then the Lucanians again. In 273 B.C. Poseidonia finally succumbed to the expanding dominion of Rome. The Romans renamed it Paestum. They built their forum, replacing the Greek agora or marketplace at the center of town, and laid down their Roman roads around the Greek constructions.

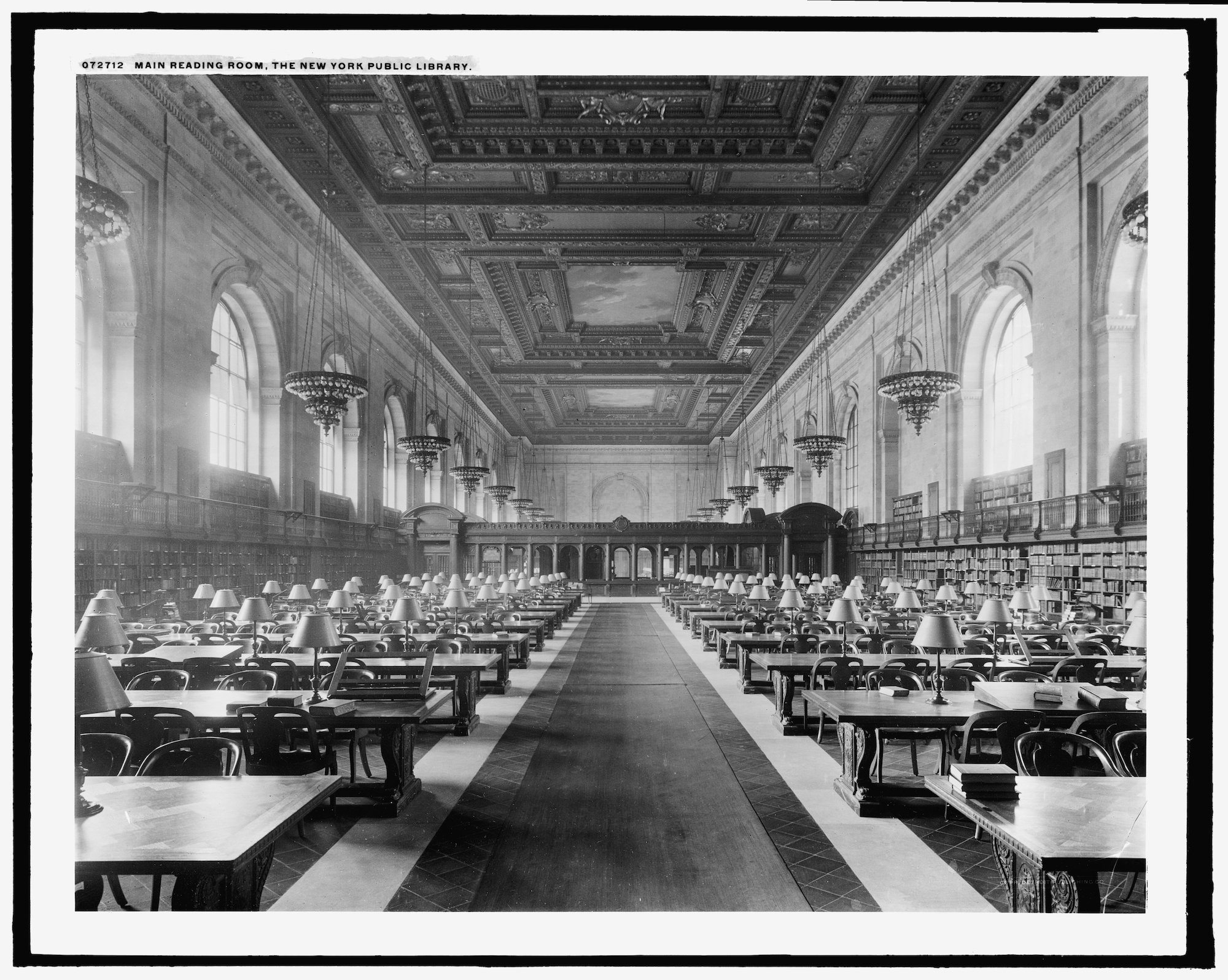

The Great Temple at Paestum, 1897. Photograph: Photographer unknown, New York Public Library.

The town lasted another thousand years, well into the Christian era, before malarial swamps finally reclaimed it. From the middle ages until the nineteenth century, when the Sele River was re-channeled and the area re-drained, the abandoned settlement remained overgrown, even dangerous to visit. The site was only excavated starting in 1907, a process that is still ongoing. Paestum’s long-abandoned state means that its two monumental temples dating from the sixth and fifth centuries B.C., at first thought to honor Poseidon/Neptune but now believed to be dedicated to the goddess Hera/Juno, are some of the best preserved ancient Greek structures in the world. A smaller third temple, dedicated to Athena and dating from the same era, also stands today.

Acentury ago, in the late 1920s, D. H. Lawrence toured his own pre-Roman sites with his American friend Earl Brewster, a painter and a scholar of Buddhism. Lawrence then wrote a paean to the pre-Roman people in “Etruscan Places,” an essay first published along with his other Italian travel writing in 1932, two years after his death.

The fate of Rome’s closest neighbors—who were among its earliest conquests—has long intrigued artists and perplexed historians. Michelangelo sketched the Etruscan tombs at Tarquinia. Piranesi composed an etching based on the Etruscan ruins at Chiusi. Robert Adam decorated the state dressing room of West London’s Osterley Park estate in Etruscan-style fresco. Johann Joachim Winckelmann made a study of Etruscan civilization along with the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. Meanwhile the Society of the Dilettanti in London discussed the Etruscans’ lack of facial hair as compared to the Greeks—a habit of grooming, they surmised, that the Etruscans must have passed down to the Latins.

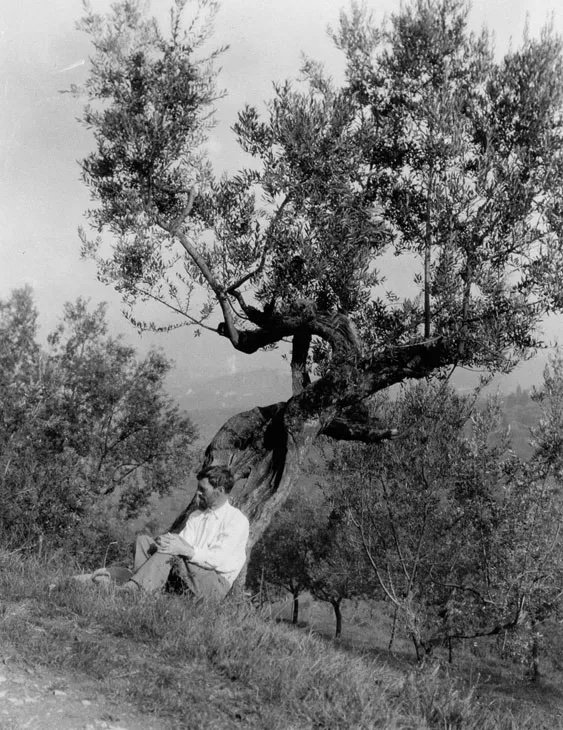

D.H. Lawrence beneath an olive tree at Villa Mirenda, San Polo Mosciano, ca. 1926–27. Manuscripts and Special Collections, The University of Nottingham. Photograph: Photographer unknown.

Veii, a southern town of Etruria just ten miles north of Rome, supposedly fell to the Roman Republic in 396 B.C. after a ten-year siege. Despite their proximity to Rome, the Etruscans spoke a language that was non-Indo-European, like Hungarian or Basque, and which today remains largely elusive. Their origins have been debated since ancient times; the eyewitness records of Rome’s own early interactions with Etruria’s hilltop settlements may have been destroyed in Brennus’s Gallic sack of Rome in 387 B.C. We do not know for certain how Etruria came to mix with its Latin neighbors to the south. Before the establishment of the Roman Republic in 509 B.C., three of Rome’s seven ancient kings—Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius, and Lucius Tarquinius Superbus—were supposedly Etruscan. The rape of Lucretia by Sextus Tarquinius, the Tarquin prince, precipitated the Roman overthrow of the Etruscan monarchy. As told by Livy and recounted by Ovid, the legend of Lucretia’s rape and suicide was used in ancient times to justify the Etruscans’ demise and has been widely depicted in Western art since the Renaissance, taken up by Shakespeare, Titian, and Benjamin Britten, among many others.

What mainly remains of Etruria itself are its tombs, which are open to exploration today much as D. H. Lawrence found them in the 1920s (I first visited the sites some thirty years ago as an undergraduate). These necropoli are indeed “cities of the dead.” The Etruscans carved, built, and painted their tumuli as second homes, hillside condominiums for the afterlife. To complicate the historical record, some of their decorations were Greek-inspired if not Greek-made—a reflection of Near Eastern influences under Etruria’s “orientalizing” period, which reached a high point in the seventh century B.C. While it was long thought that these tombs depicting the characters of Greek myth revealed the Greek ancestry of the Etruscans, archaeological consensus now links the Etruscans to Italy’s Iron Age Villanovans. Here are central Italy’s aborigines—ab origine, Latin for “from the beginning.”

In “Etruscan Places,” Lawrence took up the history of these ancient people in part to slight their Roman successors—and, by extension, the Italian fascists drawing their authority at the time from classical antiquity, following Benito Mussolini’s March on Rome in 1922.

Lawrence was not the only writer of his time to use Etruria’s ancient backdrops for modern commentary. In “Roman Fever,” her sensational short story first published in Liberty magazine in 1934, Edith Wharton alludes to Italian aviators flying two American daughters from Rome to Tarquinia for a fraught moonlit tour of the site. What distinguishes Lawrence’s writing is his first-person account of the Etruscan tombs of Cerveteri, Tarquinia, Vulci, and Volterra, intermixed with grand pronouncements and often absurd speculation. As Lawrence began:

The Etruscans, as everyone knows, were the people who occupied the middle of Italy in early Roman days, and whom the Romans, in their usual neighborly fashion, wiped out entirely in order to make room for Rome with a very big R. They couldn’t have wiped them all out, there were too many of them. But they did wipe out the Etruscan existence as a nation and a people. However, this seems to be the inevitable result of expansion with a big E, which is the sole raison d’être of people like the Romans.

In a certain way, Lawrence’s literary achievement was his ability to write, even in his twilight years, like a petulant adolescent. His analysis may be overblown. He also committed the sin of reading contemporary politics into historical events. His rhetorical deployment of the “Etruscans” could be just as facile as Il Duce’s “Romans.” At the same time, what makes his Italian travel writing compelling is the often inadvertent humor of this celebrity-radical raiding tombs among the poor paesani. “Impossible to leave an unlocked small hold-all at the station,” he bemoans at one point, when the local station attendant at Palo refuses to hold on to his luggage for him. “B. and I are two very quiet-mannered harmless men,” he elsewhere laments, when a fourteen-year-old child declines to take these two strangers to the tombs at Cerveteri: “But that first boy could not have borne to go alone with us. Not alone!” “The Etruscans had a passion for music, and an inner carelessness the modern Italians have lost,” he gathers upon seeing the painted tombs of Tarquinia. “It is different now. The drab peasants, muffled in ugly clothing, straggle in across the waste bit of space, and trail home, songless and meaningless.”

Writing an appreciation of the book for The Washington Post two years ago, Walter Nicklin maintained that Lawrence “seamlessly mixes closely observed, naturalistic details with the kind of inward reflections found in essays and memoirs. Adding spice to the mix, he never feared to offend with his sharp historical analysis sprinkled with cultural and social criticisms.”

At Cerveteri, for example, with its cylindrical mausolea carved out of the bedrock, Lawrence wrote of “the natural beauty of proportion of the phallic consciousness, contrasted with the more studied or ecstatic proportion of the mental and spiritual Consciousness we are accustomed to.” The Romans, meanwhile, “hated the phallus and the ark [womb], because they wanted empire and dominion and, above all, riches: social gain. You cannot dance gaily to the double flute and at the same time conquer nations or rake in large sums of money.”

Achilles ambushing Troilus (on horseback) Etruscan fresco, Tomb of the Bulls, Tarquinia. Photograph: Mary Harrsch.

Encountering the tomb figures of Tarquinia, Lawence likened the “sun painted” Etruscans to “Red Indians” and remarked on the visceral effect of vermillion among animistic people: “They know the gods in their very finger-tips.” It was Greek skepticism and Greek rationalism, Lawrence deduced, that “more or less took the place of the old Etruscan symbolic thought.” Finally, under Roman rule, the “Etruscan princes became fat and inert. . . . The Etruscan people became expressionless and meaningless.” He concluded: “For all of the Italian people that ever lived, the Etruscans were surely the least Roman. Just as, of all the people that ever rose up in Italy, the Romans of ancient Rome were surely the most un-Italian, judging from the natives of to-day.”

What is perhaps most telling about Etruscan tombs is how varied they could be from town to town, something Lawrence rightly noted. Some were carved into the hillside. Others were constructed in mushroom-shaped mounds. Inhumation was practiced in one place while cremation was common in another. Lawrence observed how

the Etruscans carried out perfectly what seems to be the Italian instinct: to have single, independent cities, with a certain surrounding territory, each district speaking its own dialect and feeling at home in its own little capital, yet the whole confederacy of city-states loosely linked together by a common religion and a more-or-less common interest.

To follow on Lawrence’s point, it was this regional variation that ran counter to the Roman mindset, which went on to express its astonishing power by laying down the same roads and aqueducts and temples from Africa to Judea to Britain to the Caspian Sea. Latin legend has long held that the Romans emerged from something beyond the native Italic. This was the story most famously expressed in the twelve books of Virgil’s Aeneid, connecting Aeneas’s escape from the destruction of Troy to the founding of Rome and even to the ancestry of the Caesars.

As it happens, clay figurines depicting the story of Aeneas carrying his father Anchises on his back out of Troy have been discovered in Veii. Whether these figures date from before or after Rome’s conquest of the town in 396 B.C. remains an open question. It could be that the Aeneas myth reached Rome through Etruria, or that both the Latins and the Etruscans received it from Greek sources, or that the story in fact reveals some ancestral Hellenic connection between one group or another. It could also be that the origin myth of the Latins was just that, a myth, and that the Latin stock was just as proto-Villanovan as that of the Etruscans.

What matters is that the descendants of one of these Latin settlements managed to dominate the others, and in short order the rest of the Western world. Here is a story so extraordinary that it might as well have started with the twins Romulus and Remus suckling a she-wolf in a cave after they were cast out of the town of Alba Longa. For all of the interest in Italy before Rome, Rome’s remaking of Italy remains the defining story of the peninsula. The Etruscans and Greeks and everyone else serve as supporting characters to this main event. The Etruscans may have been “dancing in their colored wraps with massive yet exuberant naked limbs,” as Lawrence enthused, “ruddy from the air and the sea-light, dancing and fluting along through the little olive trees, out in the fresh day.” Meanwhile, the Romans just down the block were out to make history.