THE NEW CRITERION, December 2022

A library by the book

On the politicization of the American library.

Adapted for The Wall Street Journal of November 11, 2022

In 2006 the American Library Association issued a button to its members. It read, “radical, militant librarian.” We should have taken the message at its word. The American library, until recently a refuge of neutral quietude, has become a booming battleground in the culture wars.

In 2018 the ALA dropped the name of Laura Ingalls Wilder from its annual children’s literature award. The reason? The supposed “culturally insensitive portrayals” in her landmark Little House on the Prairie series. Three years later, the organization published its “Resolution to Condemn White Supremacy and Fascism as Antithetical to Library Work.” The edict claimed that “libraries have upheld and encouraged white supremacy both actively through discriminatory practices and passively through a misplaced emphasis on neutrality.” The proclamation charged the ALA’s “Working Group on Intellectual Freedom and Social Justice” to “review neutrality rhetoric and identify alternatives.”

The quiet, neutral library was out. Full-throated progressive politics were in. As Emily Drabinski, a self-described “Marxist lesbian” who was recently elected president of the ALA, stated on her campaign website: “So many of us find ourselves at the ends of our worlds. The consequences of decades of unchecked climate change, class war, white supremacy, and imperialism have led us here.”

The condemnation of the history of the American library, by its own gatekeepers, has done more than bring “Drag Queen Story Hour” to every children’s reading room. It has also upended the traditional role of the library as an organization primarily dedicated to the acquisition, preservation, and circulation of books. This is a radical overhaul, and it has been brought to us by some of America’s largest cultural philanthropies.

In October the Mellon Foundation hosted a panel discussion on the American library featuring Mellon president Elizabeth Alexander, the ALA executive director Tracie D. Hall, and the Los Angeles City Librarian John F. Szabo. “Library workers are on the front lines of some of our most pressing social justice issues,” began the discussion. They are “no longer relegated to the reference desk.” What does this all mean? For one, that today’s librarians mock “the shushing part” of the traditional library: “I can’t think of too many contemporary library spaces I’ve been in where the librarian is going to be a shusher,” said Hall. “I probably was the librarian that others might have wanted to shush.” Through sewing classes, coworking spaces, and “incubators,” the panel spoke of “fulfilling the promise of what libraries were meant to be in terms of equity.” “It is our responsibility to ensure that no one is left out of the voting process,” Hall added. “That is one of our core values at the American Library Association.” And by actively appealing to voters on one side of the political spectrum, the library organization helps move election outcomes in a desired direction.

As librarians now champion controversial books such as the graphic novel Flamer, they also call parental attempts to limit what children read as evidence of a “period of unprecedented book banning and censorship”—one that “far eclipses even the McCarthy era.” Meanwhile, truly deplatformed titles, such as When Harry Became Sally, Ryan T. Anderson’s critique of modern transgender theory that Amazon erased from its e-commerce platform, are never mentioned in these one-sided agonies. “This is the third great wave of librarianship and libraries—as a social project,” concluded Hall. What was, until recently, a widely popular American institution has been nearly broken by unrestrained progressive politicization.

“I suspect that the human species—the only species—teeters at the verge of extinction, yet that the Library—enlightened, solitary, infinite, perfectly unmoving, armed with precious volumes, pointless, incorruptible, and secret—will endure.” It is easy to see how Jorge Luis Borges in the early 1940s, in his oft-quoted short story “The Library of Babel,” might have drawn such a conclusion. Yet today it appears that the library, especially the library that is “enlightened, solitary, infinite, perfectly unmoving, armed with precious volumes, pointless, incorruptible, and secret,” is the entity that most teeters at the verge of extinction.

It is a crisis of the Left’s own devising, one designed to turn the library into a scarred landscape. It is also based on a straw-man argument, with rhetoric disconnected from the historical record. Far from upholding “fascism” and “white supremacy,” the American library has been, in fact, one of the country’s most enlightened and democratic institutions.

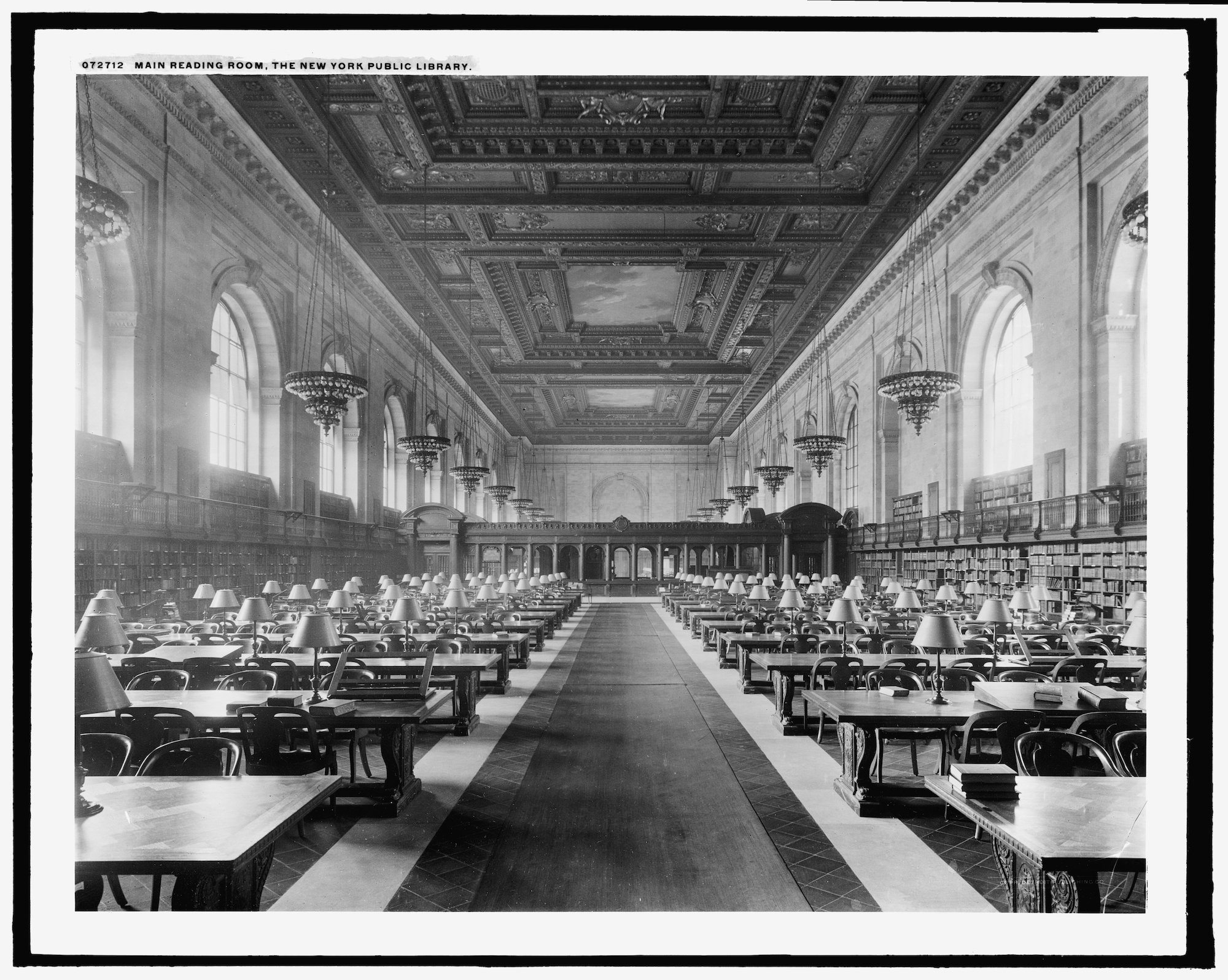

Through what remains of this legacy, beyond the spurious “banned books” displays and the circulation-desk sermonizing, today’s libraries can still be places of reverie, uplift, and reflection. This effect is due not just to the abundance of books that are—at least for now—still available for perusal. It is also an effect of the library building itself, its history of form, which records the values of an earlier era in bricks and stone.

For its ubiquity and richness, especially in those examples that survive from before the Second World War, the American library building stands as a reflection of the country’s enlightened calling. Over the nineteenth century and into the early decades of the twentieth, library design paired historicized style with the latest innovative solutions for the safe housing and circulation of its collections. The references to the history of art and civilization that these buildings displayed on their faces—and the great expense dedicated to their creation and upkeep by their underwriters—reflected a reverence for the culture of the book contained within.