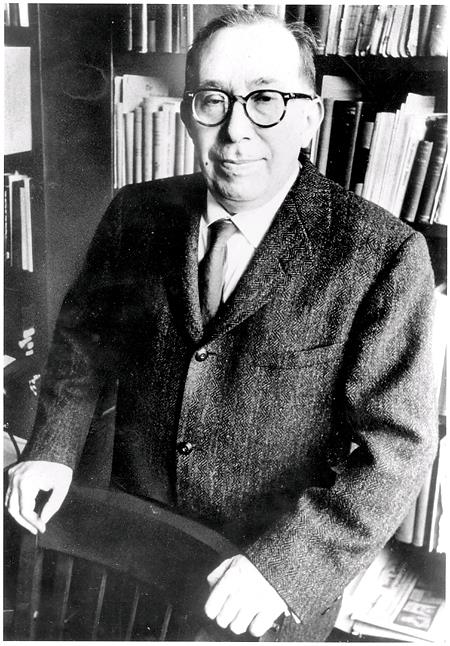

Edward C. Banfield

THE NEW CRITERION

April 2013

To the Editors:

James Panero writes in “The Culture of the Copy” (The New Criterion, January 2013) that my college professor Ed Banfield suggested museums sell their original works and replace them with passable facsimiles—a suggestion for which your founder Hilton Kramer criticized him. This gives the wrong impression. Ed thought many second-rate museums felt they had to purchase only original works, and, due to their very limited budgets, they could only afford second-rate art originals. As a result, museumgoers in smaller cities did not have the opportunity to view first-rate art. He thought that the Rockefellers and others had created copies of well-known works which were indistinguishable from the originals and which sold for relatively modest prices. Therefore, why not allow smaller, less wealthy museums to purchase these copies so their publics could view first-rate rather than second-rate art? It sounded reasonable to me when Ed proposed it, and it sounds reasonable to me now. I am at a loss to understand why the art community so violently objects to this.

Robert L. Freedman, Esq.

Philadelphia

James Panero replies:

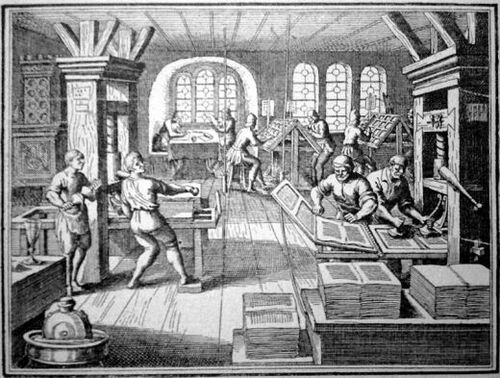

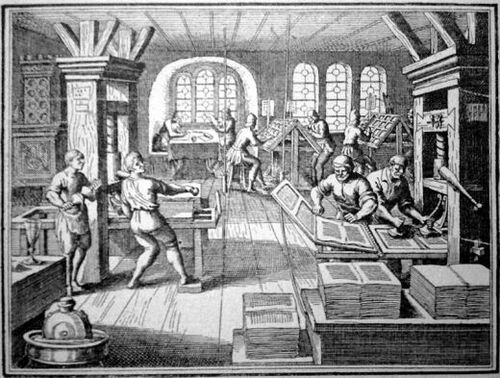

The use of copies has an important place in the history of art. This is true especially when access to original artwork has been limited. Up through the first half of the twentieth century, plaster casts made from original sculptures were used widely as study aids in museums and art academies. By mid-century, however, these casts were removed from view. In part, American museums had by then come into possession of more original work. But I would also argue that copies came to be overly devalued in relation to originals, and this was unfortunate. I am glad to hear that the Metropolitan Museum now lends its plaster cast collection out to universities here and abroad. The art museum at Fairfield University in Connecticut, for example, currently displays several Met casts on long-term loan.

In other words, the idea of us allowing “smaller, less wealthy museums” to display copies “so their publics could view first-rate rather than second-rate art” was around long before Professor Banfield made his proposal concerning art copies in the early 1980s. One could say that art-library slide collections, and before that magic lantern projections, were all copies used in much the same way as those plaster casts. The same goes today for the high resolution digital scans available through initiatives such as Google Art Project.

In all of these cases, copies serve as necessary substitutes. Their availability has been widely beneficial to a public that might not otherwise have access to great works of art. And even when originals are available, reproductions have a place, because they don’t keep museum hours, and it’s not always possible to lecture about art in a gallery setting.

If Professor Banfield had suggested only that second-rate museums use their limited resources to purchase copies, as Freedman suggests, I agree that would have sounded reasonable. But Banfield suggested much more in his proposal, and the art community was right to object to it.

“I go further,” Banfield wrote in 1982, “Why should public museums not substitute reproductions for originals?” Kramer was therefore correct in giving the impression that Banfield advocated the wholesale deaccessioning, or selling off, of museum collections to fulfill his vision. Banfield’s arguments for this were esoteric at best, nonsensical at worst, but had something to do with a desire to see the “multibillion-dollar art business . . . fall into an acute and permanent recession.” Whatever the reasoning, it was an unreasonable and vastly destructive idea when Banfield proposed it. It remains so today in ideas such as the “Central Library Plan,” a proposal to remove the books and gut the stacks at the main branch of the New York Public Library, which I mention in my essay.

At the heart of these ideas is both a contempt for the art-going, book-reading public and the elitist sense that they either don’t deserve or cannot appreciate the real thing. “It would not be unduly cynical,” Banfield wrote in 1982, “to say that many of the thousands who stood in line for a ten-second look at ‘Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer,’ after the Metropolitan Museum paid $6 million to acquire it, would as willingly have stood to see the $6 million in cash.” Sorry, but to make such a statement is about as cynical as you can get.