"Track & Field" by Allora & Calzadilla at the U.S. Pavilion

THE NEW CRITERION

September 2011

Blunder at the Biennale

by James Panero

On the Department of State's diplomatic flop at the Venice Biennale.

The United States Pavilion at the Venice Biennale has always been a tool of American propaganda. The question is what message to send. Every two years, the U.S. Department of State produces an exhibition in Venice with art that it purports to select through an open contest but, in fact, chooses behind closed doors in Washington. Since 1961, the mandate of this decision-making process has come out of the Fulbright–Hays Act, which enables the government to demonstrate American cultural interests, developments, and achievements overseas. The U.S. Pavilion reveals what the government values at home and how it chooses to represent those values abroad. One might say that the exhibition offers a unique visualization of American diplomacy.

At this year’s Biennale, this visualization includes an overturned military tank, an atm machine attached to a pipe organ, the Statue of Freedom from the Capitol dome tipped on its side, and a set of airplane seats with American athletes performing exercise routines around them. The State Department tapped the artist-duo Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla and paid them, judging from similar bequests, around $300,000 to create this assembly, which the artists titled “Gloria.”

Through a proposal submitted by Lisa Freiman, the curator of contemporary art at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the artists made six works for the Pavilion. Freiman lined up $1 million or more to finance the elaborate spectacle from a few high-profile art collectors, mostly Latin American, and the clothing brand Hugo Boss. The exhibition opened on June 4 and will be seen by an estimated 300,000 visitors before closing on November 27, 2011.

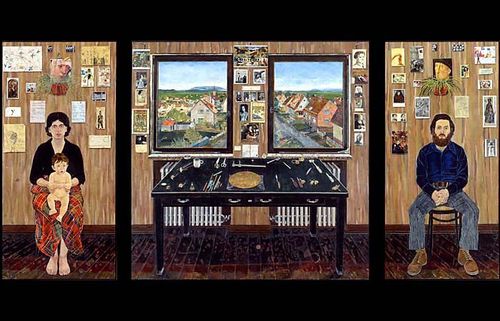

“Gloria” is a show of American power gone deliberately awry, but as a pratfall it falls flat. Nestled in a park called the Giardini near the southeast tip of Venice, the U.S. Pavilion, designed in the Palladian style by the acclaimed American architects Delano and Aldrich in 1930, is one of the more reserved structures of the thirty national exhibition halls. This year, Track and Field, the largest work of the State Department show, operates as an outdoor folly to attract visitors into this sedate building. Allora & Calzadilla, as the pair are known, took a fifty-two-ton Centurion tank, supposedly used in the Korean War but painted desert tan, flipped it on its back, and placed it in front of the pavilion hall. On top of the right tread, which clatters loudly around the tank wheels and resounds through the rest of the park, the artists mounted an exercise treadmill. Here real-life athletes from USA Track & Field, including the former Olympic medalist Dan O’Brien, jog at intervals during the exhibition while wearing U.S. team clothing. The effect, a rather unconvincing one considering the treadmill’s inelegant placement on the vehicle, is that the champion athlete is running on the tank tread itself. The meaning is that an unsubtle (and unsustainable) link exists between American militarism and athletic competition.

Inside the pavilion hall, a pair of works called Body in Flight (Delta) and Body in Flight (American) resemble business-class airline seats, on which the artists directed gymnasts from USA Gymnastics to perform a choreographed routine. The two works together provide a visual satire of the international (again, competitive) business interests of the United States.

For the next work, called Armed Freedom Lying on a Sunbed, the artists took a downsized replica of the Capitol dome’s Statue of Freedom, tipped it on its side, and placed it on an illuminated tanning bed (supposedly the UV bulbs were swapped for non-cancer-causing fluorescents). Much like the destruction of statues from the Soviet Union or more recently of Muammar Gaddafi, here American freedom has been toppled, not by revolution but vanity.

In another room, Algorithm joins an ATM to a pipe organ, creating a facile connection between capitalism and religion. For the final work, Half Mast/Full Mast, the artists filmed a twenty-one-minute, two-channel video installation on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, which was used for military training by the American navy until 2003 and has since been undergoing environmental remediation. In the video, athletes leap onto poles and stretch themselves out horizontally as though they were human flags, here not as U.S. Olympians but as, one supposes, local residents wearing scruffy t-shirts and jeans. According to the show, these performances occurred on land that “symbolically marks places of victory or setback in the island’s sixty-year struggle for peace, decontamination, ecological justice, and sustainable development.” Again the point is clear: Puerto Ricans are reclaiming sovereignty over an island wrested from U.S. government control.

“Gloria” is not a nuanced exhibition. It broadcasts a singular anti-American message created by second-rate artists that leaves little room for interpretation. In interviews, the artists, curator, and diplomatic personnel behind the exhibition have danced around its meaning with all the choreography of the athletes in the show. Their knowing evasions have become part of the performance. The artworks “destabilize existing narratives around national identity, global commerce, international competition, democracy, and militarism,” says Lisa Freiman, in coded academic language. “All of the works follow in a spirit of critical play and profanation,” add the artists. Calzadilla confesses, “I would say that it is critical about American militarism,” but also suggests “there’s a difference between a critique and being critical,” another non-statement.

Calzadilla goes on to explain that the works “don’t have a specific meaning, they don’t have a specific agenda. They’re not trying to convince anyone of anything. It’s art. We are artists, we are not politicians. The objects can have many readings.” By repeatedly denying their anti-American message, the protest artists protest too much. Meanwhile, Freiman has attempted to spin the bombastic show in a positive way by trumpeting the artists’ collaborative process as a novelty. She also highlights the Puerto Rican status of the duo, who are described as “partners” in both work and life and operate a studio in San Juan: “I chose Allora & Calzadilla because they problematize, or put into question, the notion of American identity at a moment when immigration issues are very important and who is allowed to be a U.S. citizen and who is not allowed to be a U.S. citizen are big debates with the American people. . . . It raises the question of what is an American artist.” Yet these artists are Puerto Rican for marketing purposes only. Allora was born in Philadelphia, Calzadilla in Cuba. They met while studying together in Florence in 1995.

It is one thing for a private organization to mount an art show that is critical of America, another for the U.S. Department of State to choose to do so itself. But according to Freiman, the State Department was excited to present the exhibition. In an interview with National Public Radio, Freiman reported that the State Department “knew everything! Every dirty detail.” In an interview with Artinfo.com, she reiterated the exhibition’s close relationship with the current administration: “It’s well-timed with HillaryClintonin the State Department and BarackObama in the White House.”

Freiman says that State’s “decision to select Allora & Calzadilla was unanimous.” Maxwell Anderson, the director of the Indianapolis Museum, reiterated the approval from “everybody in Foggy Bottom down the line to the secretary herself.” “We often are not very popular when it comes to our regular foreign policies,” David Mees, the U.S. cultural attaché in Rome, explains. “So it’s very important also to cultivate that softer image—what the Obama administration has called ‘smart power.’”

With this soft image of “smart power,” the Department of State undoubtedly aimed to take home the Golden Lion, the Biennale’s award for best national show. Two years ago, the American pavilion won for its survey of the American conceptualist Bruce Nauman, in an exhibition that had been selected to represent the United States during the final days of the Bush Administration. Yet this year’s show, a product of the Obama administration, lost the national award to the German Pavilion. The award for best work, meanwhile, went to “The Clock,” a masterfully edited film by the American-born Christian Marclay about the representation of time in America cinema—displayed independently of the State Department show.

As equally unexpected as the loss of the Golden Lion has been the show’s critical reception in the world press. The State Department incorrectly calculated that political self-effacement, not to mention winking anti-Americanism, would be a popular hit with the sophisticated international community. Instead, “Gloria” came off as a pandering and disingenuous exhibition sponsored by an agent of the U.S. government. Writing in The Guardian, Jonathan Jones called the Pavilion “with its stupid tank-treadmill outside and equally vacant political jokes inside . . . a national disgrace—the artists seemed to be trying to buy off anti-Americanism by turning the glib satire on themselves.”

Meanwhile, the artists were widely criticized for the derivativeness of their conceptual work and the weakness of their political message. The blogger Tyler Green lambasted Allora & Calzadilla as “salon conceptualists.” Barry Schwabsky, in The Nation, wrote that “most of their satire of American life is ham-fisted and tame.” The critic Jason Kaufman called the show “an unsubtle critique of American values.” Writing in The Brooklyn Rail, David St.-Lascaux lamented the “artists’ kitchen sink approach” that “embarrassingly overreaches.”

While waving his own politically correct banner, Jerry Saltz, writing for New York magazine, remarked that “I think being embarrassed to be an American is partly what this is about.” He then complained that Track & Field was “one of the more obnoxious national acts ever executed at a Biennale. . . . It serves as an enticingly odious metaphor for our recent wars and ‘freedom agenda.’ The only thing that could be more poignantly odious (in my Jewish mind) would be to have artists from the Israeli Pavilion located two feet away build a settlement here.”

Gloria” was supposed to succeed through its admission of American failure. Instead, it failed to succeed, in part, due to comparisons with American Biennale triumphs of the past, including just two years before. How this occurred has as much to do with the current Department of State’s misreading of its own message as it does with a misunderstanding of the history of the Department’s involvement in this international exhibition.

From its inception, the U.S. Pavilion has been a marketing tool of American interests, at first primarily the interests of American artists who wished to put “American art prominently before the world.” The Grand Central Art Galleries, a cooperative established in 1922 by Walter Leighton Clark, lined up the funds to purchase the land and construct the pavilion in the Giardini at a time when there were already twenty-five national exhibition halls in place. Delano and Aldrich donated their architectural services to the endeavor.

The Pavilion’s recruitment as an instrument of foreign policy occurred after the Second World War. In 1954, the Museum of Modern Art purchased the Pavilion and began to mount a series of extraordinary exhibitions dedicated to the foremost artists of Abstract Expressionism at a moment when the movement’s canvases were barely dry. While MOMA openly employed the help of other museums for the shows, its true partner was the American intelligence community.

Since the publication of Eva Cockcroft’s article “Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War” in Artforum in 1974, historians have lamented Abstract Expressionism’s appropriation as a political tool by MOMA’s Alfred Barr, Life’s Henry Luce, the Rockefeller brothers, and the CIA. But their strategy was a genuine example of smart power, with a campaign of cultural politics that outsmarted Communism’s grip over intellectual circles. The covert nature of their endeavor came out of an understanding that the best cultural tools abroad were not always the most popular at home, where realism was still the lingua franca. Abstract Expressionism was able to demonstrate the freedom and progress of American culture in a way that Norman Rockwell’s realism, composed in a language not unlike Soviet Realism, could not.

MOMA officially ended its direct involvement with the Biennale in 1962. The CIA’s covert cultural program was exposed in the press five years later. In 1964, the United States Information Agency, a more overt agent of American messaging, took over the U.S. Pavilion and promptly won what was then called the Biennale’s Grand Prize, a coup for the USIA as well as a triumph for Pop Art. Even as the pavilion changed hands in 1986, when MOMA sold it to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, the USIA retained final say over the exhibitions, while the Rockefeller Brothers Fund continued to control the endowment that underwrote the shows until 2004.

When the USIA disbanded in 1999, a victim of the Cold War’s thaw, control of the Pavilion finally shifted to the U.S. Department of State. Each year the chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, in consultation with the State Department, now appoints a board of art professionals called the Federal Advisory Committee on International Exhibitions

(FACIE). This board, which deliberates in secret and is exempt from the Freedom of Information Act, reviews applications collected by the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs and selects a list of recommendations. A closed panel at State then makes the final determination. This current system has been designed so that no one agency can be blamed for a bad decision. It also depends on the resources of the museum establishment, which must file a lengthy application and demonstrate an ability to raise additional funding. At least in the case of “Gloria,” however, the real problem seems to have occurred at State.

The Department of State may have thought “Gloria” was a continuation of the Biennale’s successful Cold War legacy, with an art exhibition that is controversial at home but popular abroad. In fact, this year’s exhibition reversed this historical strategy. Critics, such as Pedro Vélez, who closely follow Puerto Rican art have argued that the State Department chose “Gloria” precisely to satisfy domestic political interests at the expense of the show’s appearance abroad. Ramón Luis Lugo, a Puerto Rican lobbyist and Clinton supporter, played a key role in campaigning for Allora & Calzadilla, who are popular with Latin American collectors. Maxwell Anderson has admitted that Lugo “was central in explaining to the government what we were hoping to accomplish here.” When he died of a heart attack shortly before the opening, the organizers dedicated “Gloria” to his memory.

Worse than such lobbying is the message that audiences see in “Gloria”: not artistic achievement or inventive forms of free expression but an orthodox formulation of American political correctness. Carla Acevedo Yates, a writer for Art Pulse magazine based in Puerto Rico, sounded the alarm on “Gloria” by wondering if “the politically correct [has] entered the mainstream under the guise of the politically engaged.” Rather than truly challenge the status quo through a visual demonstration of America’s radical freedoms, the Department of State went the way of the old Soviet Union, with rigid art that satisfied a political message at home while challenging no one abroad.

The Biennale may be a playground of the jet set, but even there America should project a singular artistic voice. The ways to do so are many, from exhibiting the art that has come out of social media—America’s latest contribution to free expression—to surveying America’s burgeoning artistic communities, to showing the work of dissident artists such as Ai Weiwei. The one lesson of “Gloria” is that the world is as unimpressed by the orthodoxies of American political correctness as it was by Soviet orthodoxies or the orthodoxies of more recent oppressive regimes around the globe.