SPECTATOR USA, January 2020

Meryl Meisler’s photographs captured the family life and nightlife of Seventies New York

‘Ford to City: Drop Dead’ was the headline of the New York Daily News. To which the City said to Ford, you first. When the Daily News ran that famous headline on October 29 1975, New York was teetering on bankruptcy. President Gerald Ford had declared he would veto a federal bailout. It looked like the Big Apple was stewed.

The world had written off New York. The feeling was mutual: the city had written off the world. Between 1970 and 1980, the city lost nearly a million residents, over a tenth of its population. Still, New York attracted people who, against the reigning wisdom, would not or could not live anywhere else.

In 1975, some hundred thousand new New Yorkers were born within the city limits. I was one of them. In the same year, the photographer Meryl Meisler left the middle-class comforts of North Massapequa, Long Island and moved to ‘the city’, to focus her lens on the lives of New York. ‘What’s so great about New York? I mean, it’s a dying city,’ Annie Hall says in Woody Allen’s 1975 film, a tribute to the neurotic splendor of 1970s New York.

The worlds of that New York were smaller, more contained and more vivid than today’s sprawling, serious and somewhat sanitized city. Back then, if the town was really going under, those who remained to live through the decay were determined to dance among the ruins.

Camera in hand, Meryl Meisler captured the demimonde dancing on the city’s grave and then some. But she also looked for the life and the humor of the city’s broken streets. She did not indulge herself in the spectacle of wreckage; she set out to document its many humanizing moments. Compassion radiates from her viewfinder and lights up her subjects. In a flash, the faces of the city of my youth come alive in her images.

Members of the Village People at Xenon, June 1978

In the early 1980s, Meisler turned from Downtown to the outer boroughs and became the original Bushwick beatnik. She brought her camera to the classroom when she took up her job in 1981 as an arts teacher at Bushwick’s I.S. 291. The Bronx was burning, and blocks at a time of this north Brooklyn neighborhood had burned too, leaving families to live among the ruins. Meisler set out to tell their sides of the story.

She never stopped taking pictures, even as her teaching life took over. Thousands of images came to rest on Meisler’s negatives, slides and, eventually, digital chips. Only after her retirement a few years ago did she begin to develop this archive into exhibitions and the books Purgatory & Paradise: Sassy ’70s Suburbia & the City (2015), A Tale of Two Cities: Disco Era Bushwick (2016) and a new selection, New York Paradise Lost: Bushwick Era Disco, to be published in the fall.

Through images that have not been seen for 40 years, Meisler juxtaposes the worlds of Bushwick and bohemia, following the highs and lows of a city in decadence and decline through day and night. Her dance-club shots, taken on a medium-format camera, are flash-filled black and white.

‘Two Queens’, Hookers Ball at the Copacabana, February 1977

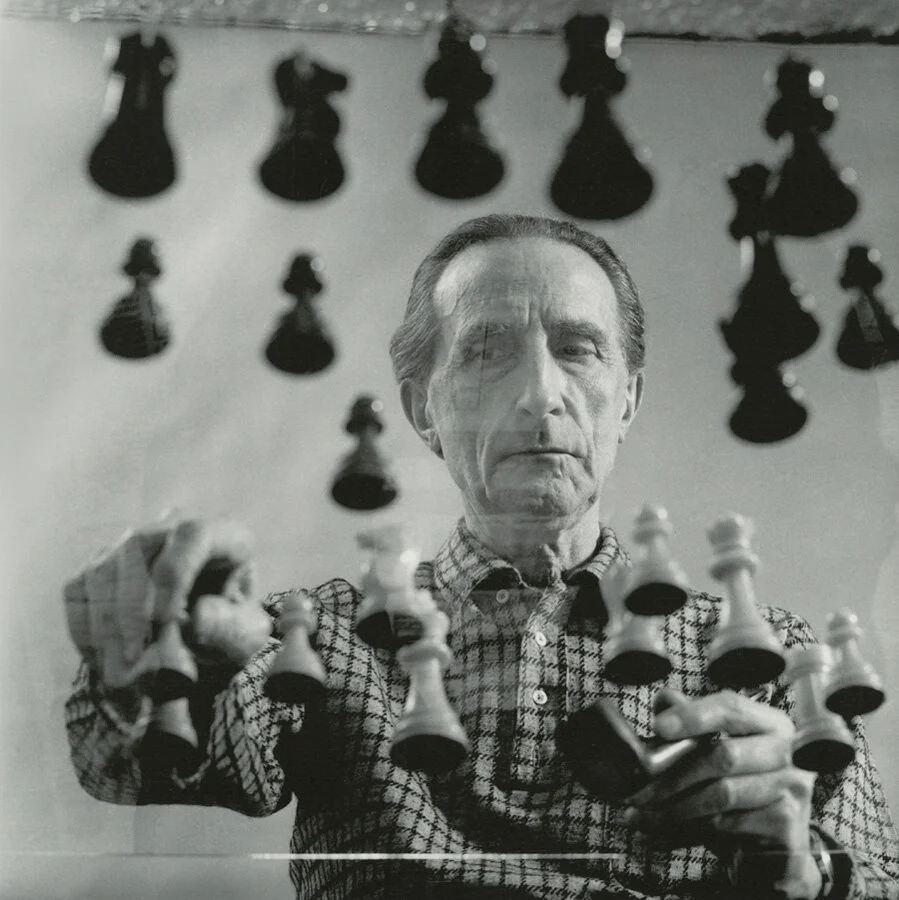

Cross-dressers preen at the Hookers Ball at the Copacabana on East 60th Street, and a near-naked man gyrates at the Jungle Party at the Paradise Garage discotheque on King Street. Famous faces such as Grace Jones, Andy Warhol and the Village People are caught in Meisler’s viewfinder.

These records of a club culture gone by contrast with Meisler’s Bushwick scenes, which she took with a point-and-shoot camera and developed as full-color slides. One consequence of the destruction of Bushwick was the opening up of the neighborhood to the sun. Bushwick, unlike the shadowy canyons and caverns of Manhattan, radiates a ruinous light. As in a city after a bombing raid, the residents of 1980s Bushwick stumble through the rubble.

Despite all the outward appearances of junked cars and the rubble-strewn streets in such photographs as ‘Red Stairs’ (1982), life goes on. Kids play among the burned-over remains or wait for the school bus by a line of wrecked cars. A toddler dresses up for Halloween, an old lady picks her way across a destroyed lot. Ladies dress up for church. Families picnic next to an abandoned car while the children make toys out of the wreckage. The day redeems the night.

George Herbert, the 17th-century metaphysical poet, said that living well is the best revenge. Even in the worst of times, New Yorkers made the best of bad circumstances. This isn’t to mythologize the destruction of 1970s New York or wish for its return. The radical play-acting nostalgia among New York’s current political class mainly appeals to out-of-town hipsters who moved into their gentrified Bushwick sublets last week. The real achievement of the true urbanites of 1970s New York is that they held on and saw their city through the genuine darkness. In the end, the city never did go bankrupt. Its salvation became a testament to everyone who now looks out at us from Meisler’s photographs of paradise regained.