THE SPECTATOR WORLD EDITION, March 2022

In our anemic age, cast-iron pans are just what we need to re-enrich the American bloodstream

I have become a pan handler — a handler of cast-iron pans. I can think of few hobbies that are as rewarding as collecting and cooking on cast iron. Skillets, griddles, muffin tins, Dutch ovens, waffle irons, corn-stick pans and much else: there was a time when America produced the finest cast-iron cookware in the world. The iron ore was abundant. So was the coal to melt it. Foundries went up across this great land. American cuisine developed around it. From fried chicken to cornbread, the American menu should still be cooked on cast iron. Southern cooks never forgot this. The same goes for soul food; black America has always prized its cast-iron inheritance. Now I find I have little need to cook on anything else. I prepare my food in the same pots and pans as my ancestors did a century ago.

My father introduced me to cast-iron twenty years ago, before its recent wave of popularity. One day, he started cooking on some inexpensive pots and pans from Lodge, the one major American cast-iron company that remains in operation today. I was not alone in my skepticism. It was a time when I still believed in “the new,” especially when it came to the kitchen. And cast iron seemed old. It was heavy. It required coats of oil. It wasn’t “nonstick.” It never really even got clean. Dishwashers, microwaves, and soap were all too newfangled for the old cast-iron technology.

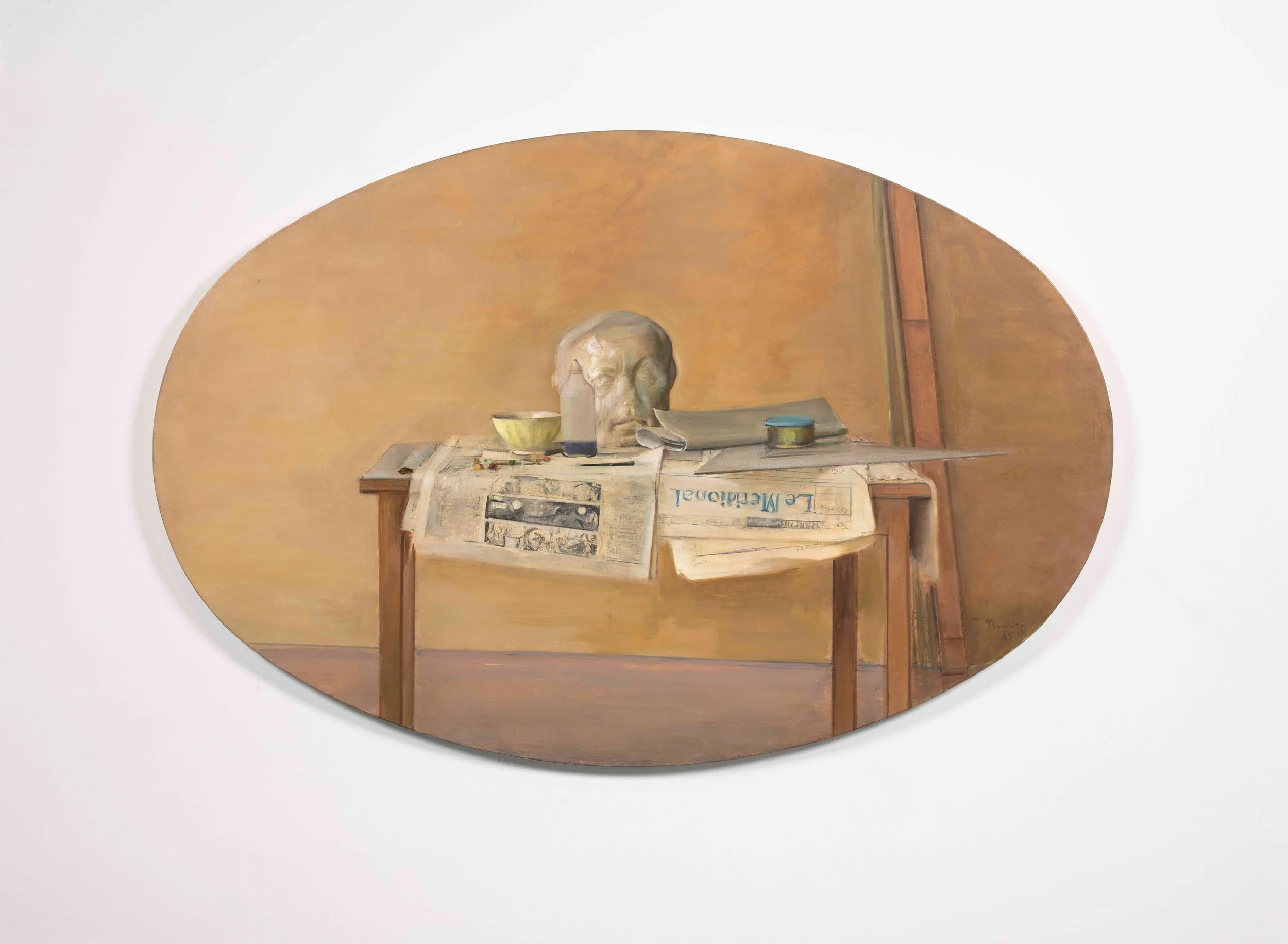

Griswold #7 cast-iron Dutch oven, produced by the Griswold Manufacturing Company, Erie, Pennsylvania, between 1910 and 1940.

But what a difference it makes with your food. You can sear meat like nothing else. You can make eggs that don’t taste like plastic because they are not cooked on plastic. You can take it from stovetop to oven to outdoor grill. You can broil, deep fry, stew, braise and bake with impunity. The more you use it, the better it gets. Unlike the modern pan that becomes a flaking chemistry experiment after a few short years — doing who knows what to your own insides — cast iron makes you stronger the more you lift it, scrape it, oil it, cook on it and season it. All the while, the healthy iron from the pan is entering your food. In our anemic age, cast-iron pans are just what we need to re-enrich the American bloodstream.

For over a decade, I have been cooking on my own basics from Lodge. My twelve-inch skillet and reversible griddle are my workhorses, as is my Lodge Dutch oven — a wedding gift from my father. At this point they are caked with seasoning, far from Instagram ready, but they get the job done without hesitation. At the latest sign of flaking, I will rub another coat of lard on them, wipe them down and bake them at 500 degrees for an hour in my oven. I am sure to keep my kitchen exhaust on high and get the kids out of the house (or better yet, use the outdoor grill) for the operation. It is the smoking of the lard that reveals the magic of the pan, as the fat polymerizes with the iron to create its own nonstick coating. Far from a chore, the proper seasoning of cast iron is one of its most satisfying traits as the pan is restored through fat and fire. You can’t do that with aluminum and Teflon.

Griswold #10 cast-iron muffin tin, produced by the Griswold Manufacturing Company, Erie, Pennsylvania, between 1910 and 1950.

“One is considered fortunate nowadays if by chance one of these iron utensils is handed down to them from the second to the third generation,” wrote Aunt Ellen, the popular correspondent of the late, lamented Griswold Manufacturing Company of Erie, Pennsylvania. For those of us with a broken chain of cookware, with the lightweight throwaways of the second half of the twentieth century interrupting our proper inheritance, there is now a robust market for vintage cast iron.

Griswold is the gold standard, with many variations and permutations of design to captivate the collector and help identify model and age. From a simple primitive “Erie” trademark, Griswold started employing a slanted-letter logo, a block-letter logo, and finally a smaller (and less desirable) branded logo. It produced skillets with heat rings and then flat bottoms. All along, Griswold’s manufacturing was more like artisanal sculpture-making than industrial mass production, as molten iron was poured into hollow sand molds. Cast iron is still made the same way today, but Griswold did it more delicately than anyone else, with crisp lettering and polished surfaces that left no trace of the textured sand.

Square waffle iron with high base, patented February 22, 1910, produced by the Wagner Manufacturing Company in Sidney, Ohio.

To add to the intrigue, as Griswold upgraded its designs, its old molds might be reused by another company, resulting in “ghost Erie” markings appearing behind the logo on Wapak and other pans. Sometimes foundries would also mold and cast competitor pans. These old recasts (and, increasingly new, counterfeits) can be easy to spot through their rougher textures. Whether you are a collector of Wagner Ware or smaller manufacturers such as Sidney or Piqua, to help differentiate there are website forums like castironcollector.com that can get as granular as the molding sand that formed these many marvelous items.

There’s much to be found on Ebay, but I have discovered the better dealers on Etsy, where you are a little more assured of a well-restored and documented item. Sure, some of these purchases can run to the hundreds of dollars. But every weekend I now get to use my No. 9 Griswold slant-logo waffle maker for family breakfast. You will never taste a better waffle than the one that emerges from these pristine stovetop paddles that were “pat’d Dec 1, 1908,” as they say right on their face. To these I have added a Griswold No. 7 Tite-Top Dutch Oven, a Griswold No. 10 muffin tin, a Griswold No. 5 skillet, and a Griswold cornstick pan — a gift from my aunt’s mother. What might I go for next? Perhaps an old Erie, or a Sidney Hollow Ware skillet, or a Wapak. Whatever I choose, the great luxury of cast iron collecting is the luxury cooking I can do on it.

Fry bread baked in a #5 Griswold cast-iron skillet.

Cast-iron fry bread:

Ingredients

¼ cup bacon drippings, filtered through a fine sieve or coffee filter

1½ cups coarse-ground cornmeal,

½ cup all-purpose flour

½ teaspoon baking powder

½ teaspoon baking soda

pinch of salt

1 egg

1½ cups buttermilk

Instructions

I use my No. 5 Griswold skillet for this one. Any smaller size cast-iron pan will do. Scoop the bacon fat into the skillet and heat both together in a 450°F oven. As it heats up, whisk together the cornmeal, flour, baking powder, baking soda and salt in a bowl. In a separate bowl, combine the egg and buttermilk and pour into the center of the dry mix. Stir until just combined. Now (wearing an apron and shoes) remove the smoking hot skillet from the oven, put it down, and carefully pour in the batter. Return to the oven and bake for twenty-five minutes. Serve hot, even from the skillet, and you will never taste a better cornbread.