James writes:

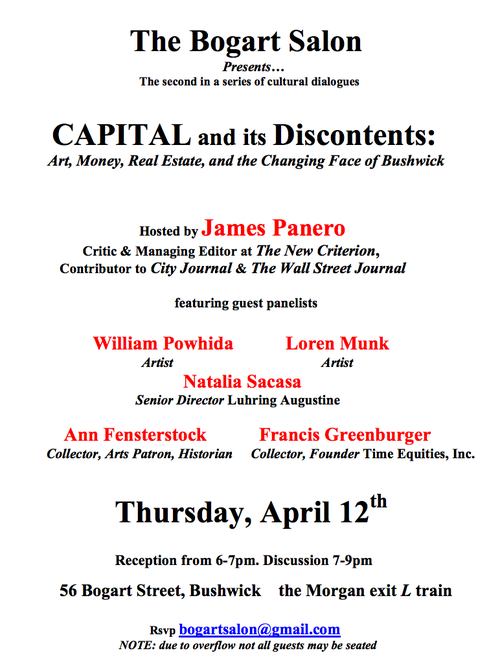

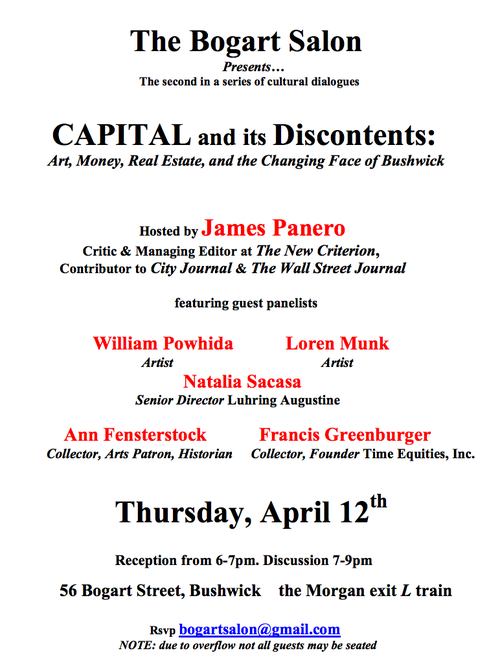

On Thursday, April 12, I hosted a panel discussion at The Bogart Salon called "Capital and its Discontents: Art, Money, Real Estate and the Changing Face of Bushwick." The participants, pictured above by Meryl Meisler, were Peter Hopkins of the Bogart Salon, Natalia Sacasa (Senior Director, Luhring Augustine) Francis Greenburger (collector, founder of Time Equities), Ann Fensterstock (collector, arts patron, historian), James Panero (me, with clipboard) Loren Munk (artist), and William Powhida (artist).

You can read all about the run up here and the follow up here.

Now below is the edited and condensed transcription of this important discussion.

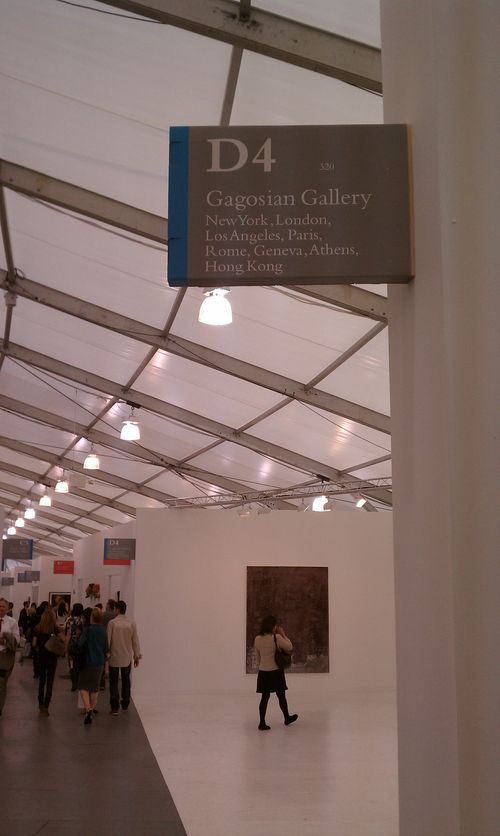

James Panero: Art, money, real estate. These three forces are changing the face of Bushwick. At last count, there were over 35 galleries in Bushwick, up from just a handful a few years ago. Until recently, the building we’re in today, 56 Bogart, was mainly used for light manufacturing. And in Luhring Augustine, one of the bluest of Chelsea’s blue-chip galleries, opened a 10,000 square foot outpost just a few blocks from here to the fascination and consternation of the neighborhood’s art community.

Let’s start with art and money, and with Bill Powhida. Bill, as you and I both read in the New York Times today, a chief executive at UBS investment management informs us that, “art is becoming more and more of an asset class.”

In your own work, you ridicule the business side of art, calling the dominance of money “asset classicism,” which is a great term. One of the things that struck me about Bushwick is that the neighborhood seems to exist outside of this arts industrial complex. Bushwick has developed a microeconomy of its own, with artists bartering with each other and tiny galleries selling work in the hundreds rather than the tens of thousands of dollars. As Bushwick begins to attract collectors, is this a good thing or do you fear that asset classicism is not far behind?

William Powhida: I remember reading your article and thinking about this idea that Bushwick was an alternative to the market, that we were trading and bartering, and that artists here were like local organic farmers or something. There was this idea that prices were low for some altruistic reason, and I just don’t think that’s the case. That’s what artists can price their work at: in the hundreds of dollars. That’s what the market will bear at this point. I don’t think for a second that there are artists in Bushwick pricing their work in the hundreds-of-dollars range for political reasons. If they could get more money for their work, they certainly would charge it. A lot of the artists I know make very traditional work. They make a few objects that they need to sell for as much as they can to support themselves.

I don’t think Bushwick is going to be under threat of selling asset-class level work anytime soon. Artists have to climb the ladder, get into that machine, get vetted by auction, and turn it into an asset class. I still see Bushwick through the lens of Williamsburg. It's the same story that’s told over and over again about up-and-coming art neighborhoods, which really is about real estate. There was an article that Roberta Smith wrote in 1998 that was called “Brooklyn Haven for Art Heats Up.” Here's a 2008 article in “New York City Real Estate News,” the title of this one was “Bushwick’s Gallery Scene Heats Up.” It’s the same story, the same narrative. Natalia here represents Luhring Augustine, called a game changer. They’re also here because it’s a storage facility. It’s not just an exhibition space. I’d be happy for all the dealers and galleries here if a tidal wave of money actually followed all the press and hype, instead of the inevitable condos and developers and real estate, which will push the artists out. My building got sold. I’ll probably be hunting for a studio further out in Bushwick.

Peter Hopkins of Bogart Salon introduces the panel. Showing: Francis Greenburger, James Panero, Ann Fensterstock, and Loren Munk. Off camera: William Powhida and Natalia Sacasa

JP: Ann, you are working on a book called “This Show Will Travel: A Cultural History of New York’s Arts Districts 1975 to the Present.” How has the relationship of art and money evolved over time?

Ann Fensterstock: Money and art have not always been as associated as they are now. Pre-1973, when suddenly this thing called contemporary art literally had a dollar sign put on it, we were not flocking to live in condos around University Place, where the Abstract Expressionists were hanging out at Cedar Tavern. It wasn’t trendy. We weren’t rushing to East 10th Street in the 40s and 50s, when those cooperatives were happening. Money and modern art were not necessarily fused. It is a relatively new notion. The launching of New York Magazine in 1968 and the New York Times decision to start a “Living” section in its pages shortly thereafter. Chic living and contemporary art started to be linked there – just as SoHo was starting to get off the ground as an art neighborhood)

While it would be naïve to say money and real estate are not the juggernauts today. There is nothing inherently evil about the serious collector. There is nothing evil about the serious gallery arriving, Natalia. What destroys the scene is "the scene". Carolina Miranda is a well-respected journalist. She wrote an article called “A Scene Grows in Bushwick,” and when New York magazine gets a hold of you, that’s when you’re in trouble. There is something very idiosyncratic and very particular about the art world and this thing called contemporary art. It attracts something called “catchet” and that’s what makes it different.

After the 87 crash. In the early 90s, the dealers have said, that’s when the phone stopped ringing. And yet, some of the most innovative dealers came out of that down-cycle in the economy. Conversely, some of the worst years, as a collector and an art historian, in terms of unthinking art, boring programs, were the go-go days of the 80s. So the lockstep of art and money is just not that simple. It is often counter intuitive.

JP: Loren, your James Kalm Report videos have reached thousands of people around the world, yet last summer you became one of the most outspoken critics of Occupy Wall Street, surprising many of your followers. You have defended capitalism and the 1%. How do you think the relationship between art and money has evolved?

LM: I would disagree with both of the previous speakers. I would say yes; Bushwick is a continuation of a similar story that has happened again and again. But I’ve been in New York since the late 70s, so I saw it happen in SoHo and the East Village and Chelsea and Williamsburg and now Bushwick, and there are new elements that have been introduced here that change to scope the whole realm of economics and art. One of them I think is the Internet. That democratization of art and art marketing has started to affect the general culture. Previously in SoHo and Chelsea, the only people who could break into that level of the art market were people that had big financial backing. Bushwick has come along with a younger generation of people that knows how to harness the Internet and social media.

WP: Loren, is there an example of somebody in Bushwick who’s doing that? I can think of somebody like Hennessey Youngman, who uses the Internet and is now leaping to Postmasters and beyond. How does that work in Bushwick? I’m not with you.

LM: I’ll give you one example; Hyperallergic has been covering Williamsburg and Bushwick pretty intensely. I’m not saying it’s happening instantly. Hrag was once writing as a stringer for The Brooklyn Rail, like you and me. He risked a lot and has been working like crazy. They are starting to get profitable. They’ve got advertising coming in. It takes a lot of time. You’re going to see these major institutions turning to the kind of thing that the people of Bushwick have been doing forever. Like everything else on the Internet, the question of monetizing this stuff is a problem.

WP: Just like Famous Accountants, they had to shut their space down. You can only do so much with an economy of enthusiasm or a do-it-yourself mentality. And they did get some great press, but in the end it’s not like they could keep running that forever on their passion and love for it without collectors buying work and supporting it and making the trip out.

LM: I hear you on that. And I’ll give you one example; has anybody ever heard of the Fun Gallery? Very prominent gallery; they were getting the publicity Bushwick could never dream of getting, glamorous, everything. They actually went broke sending work to the Basel art fair. It actually cost them so much for shipping and insurance that it broke the gallery and they had to close down. Fast forward 25 years, they were featured as the main attraction at the “Art in the Streets” show at MOCA in LA. That was an example of enthusiasm turning into cash.

Your host!

JP: Moving on to Natalia, I read in ARTINFO that you’re a Bushwick resident, and you had something to say about the Luhring Augustine move to Bushwick. Discuss some of the thoughts behind that move.

Natalia Sacasa: Nobody had any intention to be a pioneer and stake out a corner for capitalism. We have under 20 employees and the owners of the gallery try to do things very practically. In late 2007, early 2008, we were looking to buy something in Long Island City, and then economic conditions at the time made it impossible. And we admired the structures in this neighborhood. There are beautiful, solid, rugged brick buildings that were very reminiscent of Chelsea. It was a good price on the building. The exhibition space in Bushwick is where we can install things that may not be very practical for us, works that would be challenging because of their ambitious scale or multimedia or an art exhibit that is not as well known. A place that we could exhibit something up for three or six months and the audience would come around. And we thought of it as a destination. We’re here along for the experience of growing with the neighborhood. We’re also a part of a bigger international community.

JP: There’s been a narrative that for a blue-chip gallery to come to Bushwick it's somehow incompatible with the existing arts community. How would you respond to that?

NS: I think we all have the same interest in that we all want people to see our art, and so if our presence here facilitates more people coming to see our galleries then we're happy for that. We become a part of the conversation about art that's being created and that's being shown here. A dialogue between our programs can start to take place. We see it as something that can generate a more fruitful discussion rather than something that's going to be counterproductive.

JP: Francis, you must have the most diverse resume of anyone here on the panel tonight. You're a real-estate developer, a patron of the arts, and you're also part of one of the most premier literary agencies that's represented Kafka, Sartre, and, more recently, Dan Brown. Now being someone who thinks a lot about the creative process, what is it about certain neighborhoods that promotes creativity over other neighborhoods?

FG: I've been thinking a little about neighborhood change. If you're lifelong New York as I am, and I'm sure many of you are, we've all seen dramatic change. Change in neighborhoods is driven by some change agent which drives change in the neighborhood. It's certainly not always art but sometimes it is. I go back to the Upper West Side in the '80s, where people wouldn't walk alone on certain parts of Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues, and certain restaurants came in and changed the nature of those locations. If you think about the meat market, suddenly it became a very different neighborhood from what it was before. However, interestingly, if you think about Chelsea, it was not created by artists. I remember going with Paula Cooper; one day she said "Francis, let's see what's going on in Chelsea, maybe it's time for me to move" (She was one of the pioneers of SoHo). And a couple galleries were already in Chelsea at the time. In the end she of course bought a building that was more suitable for her, but that was for gallerists who thought that the area they were in, SoHo, had gone in a different direction and was no longer hospitable to the exhibition of art, mostly from the point of view of cost as well as the point of view of collecting.

JP: I appreciate that history; I'm working on an article about now in the Upper West Side, and I attribute its resurgence to the co-op revolution overtaking rent control. But my question was, what is it about certain neighborhoods that seem to allow art to develop so vitally?

FG: This is the bias of a real-estate owner and investor, but every artist needs to have a real-estate strategy, because all artists deal with unstable income flows, and beginning artists often have uneven income flows or no income flow. They have less income and predictability than even people who have a weekly paycheck that can define where they can afford to live. So the outcome is that artists regularly seek out cheap real-estate, because cheap real-estate is easier to afford than expensive real-estate, so there's almost always a migration. If you're in New York or if you're in Berlin it's no different. It's not the only change agent that enters the discussion; artists and the ambiance they bring is something that's attractive to other people. Maybe they're not artists themselves, but they're interested in art, or galleries, and eventually developers follow them too because developers want to go places where there's cheap real-estate, and people who want to be there. So in terms of what makes a particular area attractive to artists other than being cheap, it's usually larger spaces like studios. Artists don't really work well in tenement apartments that are 400 square-feet. So areas that have those types of building styles have been the areas that they've gotten into: you've got SoHo, that's why they're in Williamsburg, that's why they're here. When areas change and they get priced out, it's generational. There are still artists in SoHo, there are artists in Tribeca. It goes back to that artists' real-estate strategy; wherever you go is likely to see values increase, so you should buy quickly if you can.

JP: Bill, I think that's a common experience as neighborhoods change; as artists come in there's a gentrification that occurs and then the real-estate developers come in and artists are kicked out. Is that how you see the process?

WP: Part of it is that the term gentrification and the role artists play is sort of like a canary in a coal mine. Unless you are independently wealthy or have trust-fund, for an artist to buy something is highly unlikely; you might be able to scrape something together if you got a condo or a small house but certainly not the kind of spaces that we need to work. And so if we're talking about a real-estate strategy, then artists need to have a much broader strategy, somewhat like a corporation where it's not about individual property rights like "I'm buying this studio and I'm going to hold onto it until I die" but something more like stewardship as opposed to ownership. Because, in the process of gentrification we move to neighborhoods because we do need all those things; we need large spaces. Most artists do work; they have a day-job, full-time job, or part-time job to help cover the incredible cost of living in New York. I know a couple artists who make a go of it without working but their lives suck. When gentrification then happens, it's not artists who are buying the condos and displacing people. I know a lot of the artists in Bushwick are white, and a lot are dudes, but there's one thing we have in common with most of the local residents who lived here before: we're working class, and that should be a point of solidarity. The negative side of that is that people are being driven out, but we can do something about that. There was an OWS question from James; interestingly, there's no Occupy Bushwick. There are some artists who might go to Occupy Arts & Labor or Arts & Culture, but even Williamsburg has an Occupy Williamsburg. I know they're probably a bunch of douche bags—it's like a private club now and they can afford to get arrested and go nuts—but I'm surprised there isn't an Occupy Bushwick. I mean, start talking to each other and figuring out ways to buy some property. I know it seems out of our reach for commercial properties that have large down payments, but collectively it seems possible. And a lot of artists, if they do have money don't talk about it because it's "not cool, not authentic." So there might be more money than we realize for artists to start buying some properties together so we can break the cycle of migration and movement. And that's one of the great things I like about Bushwick; I see a lot of artists I know here tonight and I like hanging out with them, I like seeing their work and talking to them. Even if I dislike what they make sometimes, it's great that we can have those arguments within an artist community.

AF: You said a couple interesting things. If you want to talk to Penny Pilkington and Wendy Olsoff from PPOW in the East Village or Magda Sawon from Postmasters, time and again, very often the agitator behind the desertion of Williamsburg and going to Chelsea, leaving the East Village and going over to SoHo, is gallery owners who are afraid to lose their artists. Artists want the next show in Chelsea or SoHo, artists want the prices, artists want the critical discourse; there's nothing more debilitating for an artist to put on a great show without the critical reviews. So the notion that artists aren't a catalyst in this is just not true.

WP: And I'm not saying that. When I disagreed with James earlier about the idea that Bushwick is somehow different, that it doesn't have the same aspirations, I meant that artists just want to have a bigger audience, they want to go somewhere their art can be appreciated.

AF: Wanting to hang out in the right community is a double-edged sword, and that's also always been characteristic of these kinds of neighborhoods, because artists want to be around other artists. They want to drop by studios, they want reinforcement when work's not going well, they want congratulations when it is going well— it's not about the money per se but more about the catchet. If people only wanted to live near a luxury product, they could live in the jewelry district or move in next to the Ferrari dealership on Tenth Avenue. But we never do that because it's not chic; the minute you get these communities which happen again and again (and Chelsea was different because it wasn't originally an artist community but started with galleries), you get the community, then you get the scene, you get the catchet, then you get the gentrification.

WP: I take offense at artists being used to market something else and then being shifted out, but I also agree with you that artists aren't some blameless fucking saints; we want things to be green but we also need a lot of time and space and those things are really expensive in New York City. And artists want audiences as well. We want people to see our work. One of my friends here tonight does one-night-only shows because it all happens at the opening anyway.

JP: I think there's an additional factor, which is density. I think artists don't just seek out the cheapest space; they seek out the type of space where other artists are because it has to do with a particular type of urban density where artistic innovation occurs. You need to reach that critical mass before you get that explosion of creativity.

LM: Well this is where I diverge from Francis saying that artists just need cheap rent and a lot of space. If that were the case, then everybody would've just moved to Detroit years ago. As a matter of fact, there are people in Newark with spaces that are huge, and they would let you have them for damn near free: "Just come over, bring your artist friends!" New Jersey people might have these 10,000-square foot studios but they can't get collectors to come by, they can't get other artists to come by. So I think if you talk about the cache in the artist community, one of the most important parts of it is beyond the space and the cheap rent and all that stuff; it's a place where people pay attention. And if you don't have people paying attention, you don't exist. That's what people are killing themselves for. I think the other aspect is that it's unrealistic to think we can just come up with an idea and stop this. That's just not going to happen. I think a more realistic view of it would be to accept that this is just the way that life is, and figure out a way that most people can benefit in the best way from this ever-going, ever-expanding thing that's happening instead of saying we can change or remake the world. You look at it and say "this is what's happening and it's inevitable, but how can we be creative and use this in the most positive way for the most people?"

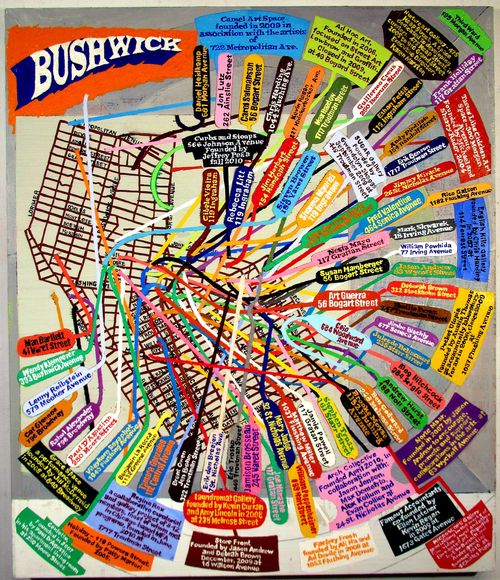

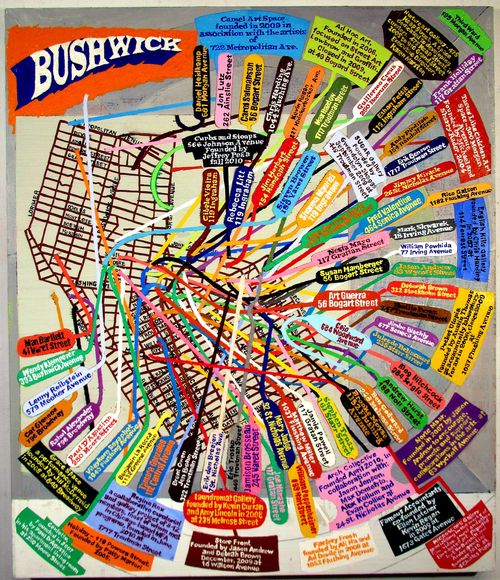

Loren Munk, "Bushwick Map (study)" (2010-2012), 42 x 36 inches, oil on linen.

NS: A lot of people are watching our arrival in Bushwick. It seems like the greatest resentment is because we've somehow stolen the thunder of those pioneers here, who marked out the territory and claimed it as a community and cultural space, that we're somehow taking away the spotlight from the people that have been invested here. And that uproar is kind of in line with that sort of scene-killing that Ann was talking about. I mean, this sort of screaming about the legitimacy of the scene here is probably going to make more people want to purchase studios here and have their spaces here. It's going to bring attention, but it’s going to be almost the attention that we're trying to avoid, whereas if we want people to stop coming here… button up, don't tell them how great it is, don't tell them what we're doing.

FG: I think there are certain things a community can do to control the way it evolves and grows, but, fundamentally, it's a complex phenomenon. Yes, not only do artists want contact with artists, but other people do and other institutions do. You know, I have a house in upstate New York near a town called Hudson. They made William Kennedy's movie there which was set in the Depression, and they didn't have to do any sets! Anyway, now it's evolved; all the antique dealers went up there from New York and that changed it. They've opened a hotel in Hudson, there's a new performance theater being designed: this stuff has a dynamic. I remember going to a dinner and being told that it was black-tie, and I thought "nobody in Hudson holds a black-tie," and when we got there we were seated at a table and this couple there said "oh, we just moved here from Barcelona." I said "Barcelona, and moved to Hudson?" and they said that they had heard it was the popular place. And they were an older couple; she was very old and he was a little bit younger. So positive change brings new people. And I mean you can have zoning laws, like the Upper West Side has decided now that they don't want large stores. I mean, you could pass a law saying that you don't want art galleries, but it doesn't seem like that's what anybody wants!

AF: We all know examples of galleries and other art institutions that have not succumbed to the migratory instinct. Everybody here knows Joe Amrhein of Pierogi, and Joe has made a decision to stay doing what he's doing, the way he does it, in Williamsburg. And he's seen them come, and he's seen them go. I talked to Joe and I talked to Susan recently about what they do, and people often say of Joe that he's an exception; that he's happy just to "grow" artists and see them move on, but he's not happy. He's just happy for them, but nevertheless he's chosen to stay for all these years, and never chose to get non-profit status because that is complicated and you have to get grants and you had to have boards, and that would take away from what they did which was spontaneous and nimble and responsive. Momenta Art (and full disclosure, I'm on that board), we moved from Williamsburg to Bushwick to be closer to the center of where the arts are. Always our mission has been to keep it small, keep it intimate, and keep it responsive. We don't want big, and there are choices that can be made and they exist again and again. There's a certain contingent stayed in SoHo: June Kelly never moved from SoHo, Nancy Hoffman didn't move until like 2006. They believed in SoHo and they stayed there and they did what they did.

JP: Francis, I want to ask you, because you brought up the "z-word", zoning. The New York arts community often developed by breaking real-estate regulations. SoHo and Bushwick were both settled as illegal residential conversions in manufacturing zones that then later got tenant protection. So could you talk a little more about how this zoning phenomenon in New York affects the arts? And second, could the city be doing more to help foster arts innovation?

FG: Well the issue of artists and others who move into industrial zone buildings and live there contrary to zoning laws is an old phenomenon. Generally, the city has a tradition of not wanting to give up industrial zoning, and popular wisdom is the reason it does that is to help protect industrial blue-collar jobs. I don't really know what their thinking is, but another possible motivation is land-packing, where they want to control the pace of growth. So the city has been very slow to re-zone any number of areas, sometimes with that artist occupancy and sometimes with other occupancies. In the Garment District there are certain areas where you can't have offices. West of Seventh Avenue in the 30s and 40s you're not allowed to have more than a certain percentage of the building be offices, which is theoretically to save room for the garments. Well the garments are gone, they're not coming back, they've moved to China, but there are constituents who want to protect them, or protect the premise of the district. So, what can artists do to make their living conditions more legal? Clearly, they may want to do that and they may not, because when you make them more legal, there's more competition from others than in a purely residential community. So to the extent that you want it to be legal, you can try to lobby the city.

WP: As soon as you change the zoning up here, that's when condos would probably go up, if it was zoned residential. You talk about Williamsburg, I mean, it's not complete yet but it will be like Battery Park City. There's already like two or three drug stores on Tenth Avenue, and that's just mind-boggling because nobody was there a couple years ago.

AF: That section of Williamsburg was still designated for industrial development, and, right up to 2004, it was held that way, but it got mired in a variety of very ugly pollution fights, all of which involved more disenfranchised, poorer residents, such as immigrants, who probably couldn't fight back. And very much of the endangerment of Williamsburg at that time was because it was protected for industrial purposes, and part of the argument for rezoning it as residential was that it would help keep out Radiac, it would keep out the garbage dumps, et cetera. Brooklyn so often in its history has been used to serve Manhattan's garbage and electricity needs, so rezoning was intended as a positive crusade at that time.

FG: The artists' classic theoretical solution was the AIR zoning that was applied in SoHo, but just as artists overran the industrial zoning, non-artists overran the AIR zoning. And you know in the early days AIR, which for those of you who don't know stands for "Artist-in-residence," only people who were certified to be artists could live in any of those buildings in SoHo and NoHo. What happened over the course of time was that the definition of who was an artist became wider and wider, and pretty soon if you owned a work of art you were an artist.

JP: I'm going to go back to what you said about artists needing a real-estate strategy. One thing that you said that was interesting to me was that artists today are not usually capable of buying into neighborhoods, but that's different from the past. We know so many artists who bought into SoHo and Tribeca in the '70s.

WP: Well I was going to mention that there have been historical periods when artists have gone in and been very positive agents of change, and one of them was George Maciunas, who went in and basically created SoHo. I think he went in and converted eighteen to twenty-two of those huge cast-iron buildings into artist housing. But the problem is that to do that, to be an artist who says, "well now I'm going to do real-estate development," is that's going to become the center of your life.

JP: Natalia, I have another question for you, and this is my personal observation. These days it seems that most art I admire is worth close to nothing, while the art I couldn't care less about sells for millions. So am I missing something?

NS: No, I have often thought that a lot of times we are missing something, and there's a certain sort of groupthink that happens in the art world, and it serves an insecurity of taking a leap and saying first that you like something that's different or unusual or that may not seem to hold value. But when someone starts to whisper that it's good everyone jumps on board right away. So I think a lot of the art that rises to the top is because no one wants to shout out otherwise. I mean there are a lot of things which I personally dislike and can't understand how people could feel otherwise. But it's definitely a matter of opinion. I think around 2008 Jerry Saltz had just written some article about the economy and he said that "now we can expect to see some good come out of this, because now that it's not about money anymore good art is going to rise to the top." You know, just because people have money doesn't mean they're going to foster the promotion of good art. There are a lot of people with bad taste and a lot of money.

WP: Yeah I was thinking about that; there was the idea in 2008 that the market had gone bust because the stock market had crashed. And it did tank a little, but then it just took off. It was like "we don't even have to pretend that we're productive to the economy, and we're just going to go full-bore now."

FG: This is sort of the moment when art started being labeled an asset class. Because I mean rich people are still rich, and they're just putting their money in different places when they're not investing in the stock market. And I think a lot more people started investing in art and seeing it as an asset class when they saw that art appreciates quite quickly in value when everyone is on board.

WP: I think a lot of the problem with criticizing the asset classification of art is that most of us have nothing to gain from that. I'm not going to be buying a Richter any time soon. And I mean that's just a discussion that happens in public that most of us have no way to participate in. When Jonathan Binstock wrote his evaluation of the Richter paintings it was like "they're delectable" or "this one is especially creamy"; there was no talk of its conceptual underpinnings, or why the work might be important to the artist, it's just that the shit looks good and it fits in an elevator for your Park Avenue apartment. It's a conversation that just rubs you the wrong way. I happen to make work about this stuff, but for the rest of us, it's like "who's having that conversation? I don't care, I can't afford that," and it's really annoying. What underscores this conversation is that if you have money you can buy property, you can go buy whatever art you want, you can create value, you can create something that has no value whatsoever, like my drawings, and make them worth something. Money makes everything easier; you don't have to lobby very hard when you have enough money, you can just talk to the right senator. The Rubells own a hotel which hosted an art fair in a non-gentrified area of D.C, but they would like to see their property values go up. I mean, it's not happening in Bushwick, thank God, because there are no giant hotels, but it's this underlying thing being used to do a lot of things with money: launder, create credibility. Like UBS; they fund the Guggenheim and say "we're good people: look at us, we're not doing horrible things" like selling arms, or laundering arms money in Africa. It's the way that art tends to be used that annoys me, and I'm not saying that it's not complex and nuanced, but I'm saying that from my perspective it looks kind of shitty and that there are a lot of things that just appear different when you're a struggling artist.

FG: I'd like to speak up for a different perspective. In my experience, the art world, or the world of collectors, is divided. I collect art: I've never sold a work of art, I never intend to sell a work of art, I've never considered what a work of art will be worth, it just makes no difference to me. If art that I look at is expensive, it's the opposite; it's a disincentive to me because I don't have that big of an art budget. There aren't lots of things that I like to be expensive. A very close friend of mine is a major collector of art; I think he once sold something, he said, because he felt guilty because he didn't want to take any more money away from his estate for his kids, so he sold it so that he could buy other things that he liked.

AF: Or you sell older things from your collection, which are from artists who are now established, and put that back into your personal art budget and you buy younger artists. And I support you, because not every collector in the art world is extremely wealthy. We started out collecting prints: about 1,500 dollars, 2,000 dollars, and we bought more expensive things in the good years and less expensive things in the not-so-good years.

NS: You have to believe in the value, right? And the money is never divorced from it in terms of your art budget. You're not indiscriminate about the amount you're going to attribute to that art object. I mean, you worked hard to earn the money and you're not going to part with it easily if you don't believe the art is worth that value.

FG: So that's my world; my personal perspective and the perspective of a number of collectors that I'm friends with. On the other hand, I know collectors from the other side of this. I have a very close friend who's totally on the other end. He loves art, and he's collected his whole life, but he's also gotten into speculating on art. He's allied himself with a friend of his who's an art dealer, and he's buying multi-million dollar purchases in the secondary market, and that sort of thing. To me, that's not about art, it's about buying the stock with this price hoping to sell it for that price. And there's the presence of this in New York, I'm not denying that. But for many art collectors I know, that's not the motivation, and I know many more of that type than I do the wheel-and-dealer types.

AF: You're talking about artists in commercial galleries; a big thing that makes up the Bushwick community now and it did for Williamsburg is, let's not forget, non-profit spaces. They are there very often showing emerging art, or showing socially or politically difficult art, or art that can't be installed in a domestic setting. And in these spaces there's no return on the money that's behind them. And yet people need to give to these spaces, they need money to run, whether its government grants, foundation money, private philanthropists or artists donating work for benefits. It takes money. I don't want to embarrass Adam Simon, who is here tonight, but Adam used to run Fine Art Adoption Network, which was his crusade to turn the relationship between artist and collector on its head. Instead of the collector with the money having the call to say "okay, I like that piece," the artist was the one who got to say who was qualified to own their work. And so over the years Adam's put out the works of over 350 artists, and you have to say why you feel most qualified to own it: why you believe in it, what you get about it. And the artist chooses who adopts that piece of work. But in order to do that, Adam had to get a grant, and so it was Art in General, a non-profit whose board put up the money, and who, doubtless, works very hard to get these kinds of projects done.

LM: So when you talk about Bushwick and the art world it's more than just the galleries. We'll all agree that it's naïve to think that this influence of capital and real-estate isn't going to happen, but there are many other avenues that can continue to be cultivated. This building, for example, is a mix of affordable artist studios, not-for-profit spaces, and commercial galleries, and these are people who continue to participate in the Bushwick community.

WP: Only as long as the nice owner of this building wants to keep renovating the spaces, maintaining rent controls. Because people like getting money, I'm curious about the actual business. Who's going to make money? I know Agape is going non-profit—just a broader issue, when artists show at non-profits and when they love non-profits, there's this idea that the art world operates on a different level and it's not about commerce. As if it's authentic and it's real, it's not about money. But it's always about money, and it's just this kind of separation that's put up—like they're called galleries, they're not called shops and people come look at the work and the prices are tucked in the back—it's not really something you're supposed to talk about. For artists, because it is priceless, you can attach whatever price you want to it, so if you want it to be ten-million, it's ten-million, and that's just whatever the market will bear at a certain time. And it's sort of frustrating from an artist's point of view to just be working for exposure on the premise that eventually you'll sell and make a lot of money, and it's just not true for most artists. We talk about the success stories but we don't talk about what comes after that. For all the talk of Williamsburg, some galleries did make it but Roebling Hall didn't make it; I mean they were a crash and burn casualty.

William Powhida, "What Do Prices Reflect?" Graphite, watercolor, and colored pencil on paper, 2011. Courtesy of Postmasters Gallery.

JP: Let's leave it there; we've had a very well-behaved audience tonight and I wanted to leave some time for questions. So Adam [Simon], I'm going to turn it over to you first. You've come up quite a bit in this discussion so I'm just wondering what's your response to what's been said tonight?

Adam Simon: I have one major concern, which was sort of addressed in the very beginning, which is the question of "scene." You said something about a real-estate boom happening without the art boom, that's just putting it in commercial terms. But what I'm concerned about is that the real-estate boom happens without allowing the artist community to actually go through all the stages of creative growth that it should be allowed to. Because, as Ann might've mentioned in her book, you have to think about the amount of time it took SoHo to develop, the amount of time it took the East Village. And what's interesting is the time sequence. And what I saw in Williamsburg and I'm seeing in Bushwick is you have buildings like this that are commercial buildings, and the owners realize that they can sell smaller parts of buildings like this to artists and make a lot more money, and the businesses are the first to go from these commercial buildings. And as soon as that happens, you have a collection of smaller sub-divided art studios, and you have the cache we talked about. And what I'm afraid of is that you don't really get a fully-developed artist community.

LM: I don't think we can sit back and say this is the way the process repeats every single time. We're in a constantly evolving situation; things do not stay the same. I've been writing about the Bushwick art neighborhood since 2004, so for me this has already been going eight years which is as long as the East Village scene lasted. It's a different thing, different people, different approach, different kind of neighborhood, so I don't think we can expect this to go the same way. We need to accept the fact that this is different.

[Audience member]: I have a question that relates to what you're saying: the thing about the Bushwick scene I'm curious about is does it equate to a certain type of art-making that's happening here, and that's something that we haven't talked about, which is what is the art that's being made here? What are the questions that artists are thinking about? Is there something new that's emerging? Is there a movement? And so this may relate to Adam's question about whether there's enough time for that to generate, and I wonder if it also ties in with your earlier question, Loren, about the internet and whether such a thing is even possible now because we're all so connected and information's flowing. Is there something unique about Bushwick where art-making is concerned, and if not, is that because of the internet or is it because of money and real-estate?

WP: Can I just make one point related to that? It's not Bushwick; Bushwick is a place, it's like Tupperware. It's what's coming into it that's unique. What we have is lots of students from graduate programs from all over the country who recognize this scene; they know that there are studios in Bushwick and that there's an artist community. And everyone parachutes in and we're all outsiders. But you just backtrack: what's going on at the University of Kansas? What's going on at whatever MFA program they're all doing before pouring in here? The image I'm drawing here is a hole where everyone is just coming out of graduate school. They're just coming here and hoping that they can make it. And there are tons of artists competing for the opportunities; Bushwick Open Studios is coming up. There are hundreds of open studios and those are just the ones with people signed up.

LM: I just wanted to give a shout-out; this was shared with me by our "den mother," Deborah Brown. She had a meeting two weeks ago and she very carefully started plotting out the list of the new galleries. When I started covering the galleries in here there were maybe four or five galleries: Pocket Utopia, Ad Hoc Art, English Kills and a couple other places. Now she's got in here thirty-eight. Now, hell, Bushwick is over. It's Ridgewood where the happening scene is now, it's already moving on.

[Audience member]: I'm trying to follow what you're saying: so out of all of these millions of people coming here, is there space for people to meet and get inspired and commune around the work, or is everyone too busy trying to make it?

WP: Well that's definitely true, part of being a professional-level artist is networking, but I was just talking with Kevin Regan and the one thing he was lamenting was artists not spending enough time in each other's studios. But it is happening, you can't deny that it's happening, but probably not in the way that we would like to. And when that open studio happens and there are 350 studios open you can see about a tenth of it if you're industrious. So we're in this weird time. We're all so busy trying to climb that ladder that we might not actually be growing.

[Audience member]: Well I disagree with you; I know somebody who has a gallery here and spends time going to studios and artist-run events like the thing that David Bates put together in the church. I'm running a gallery and I'm going to show some of the people I've seen in artist-run shows, and now when people say "come look at my work" it's more likely that I'll see them in an artist-run show that lasts an evening, and it's up to me to go and see as much of the floor as I can, so I am in people's studios. That's how you get an idea of who you want to show: from other artists, from Small Back Door, from Bobby Redd Project on Bushwick Avenue in a church. I've gotten lots of good ideas from other artists, and I don't think I'd have an interesting gallery if I didn't go to other people's studios and see their work. And I do talk to them when I'm there, and it helps me make my own work (and I'll plug myself): I'm an artist in Manhattan, and I think I would've stagnated if not for the exposure to other artists' work and their advice. So we are really busy, but in some ways the busier you are the more ideas are going through your head. And the ideas are all really vital; I've had a really good dialogue with a lot of people here and it's helped me a lot.

JP: Question in the back—

Eric J. Henderson [from the audience]: I'm an artist, but also a writer and a poet and I write about art policy. My question is: capital has an aesthetic—and there's always something real there. I'm not a pessimist; there is something real in Williamsburg, something real in SoHo, something real in Bed-Stuy. But I'm wondering, what is the aesthetic that forms the base of what can be art? How do you compare the aesthetic of capital with the real core of creativity in the heart of those neighborhoods?

AF: I'm not sure I understand the "aesthetic" of capital—

EH: The aesthetic that people want. I mean, you won't be able to sell some of these works for more than a couple hundred because they're not in what people would call "an asset class." There are huge gaps between those asset-classed works and the more generally creative stuff.

AF: But there are also huge gaps between moderately-priced art works and highly-priced art. But there's not always a huge aesthetic break. You can go into some of these up-and-coming Lower East Side galleries now, and see what looks like a pile of DIY stuff pushed together, but if it's good, it's starting to get pricey. I'm not sure that I agree that there's a capital aesthetic. You could spend a lot of money making Jeff Koons, who I think is brilliant, but also Takashi Murikami, which is, in my view, dreadful, dreadful stuff. So I'm not sure that money and taste are necessarily symbiotic.

EH: I agree that they aren't, but I think there is a type that accords to what's selling. For example, when I look at Powhida's "Hooverville," I think we missed a WPA moment.

LM: I would say that there is an aesthetic to expensive art, or to art that the wealthy want, but it is not particularly artistic; it's a financial aesthetic. I was in a German art town, and the guy that was in there walks into the show and introduces himself to the dealer. He says "hi, you might know me: I'm the guy paid 2.8 million dollars for the George Baselitz at the auction the other night." That right there told me: there is the aesthetic of money. There are people who are building museums and they're hiring curators and they're paying magazines to print their advertisements. There is a class of people and that's what they're looking for; it's like "Well gee, this is beautiful because I'm going to buy this "artist X" for sixty grand," just like an economist would say "I can buy this for sixty grand and in three years I can flip this for 250 grand, in a slow market." That way, there is an aesthetic attraction for them as a financial instrument. And though sometimes we say that artists are pure, unfortunately if you look at some of the greatest, best known artists of the twentieth century, they were playing that game. They were using those kinds of people to finance some of their experimental stuff. I mean we're talking about Don Judd; he couldn't have gone down and done his things in Texas if he didn't have people who were using his work as financial instruments. As work exists as art, it also exists as potential assets like anything else. I mean, it exists equally as well as a financial instrument as it does a piece of aesthetic value.

JP: Do you think there is an "asset class" aesthetic? Do you see a certain type of art with the tendency to push up the speculative value?

NS: I think it tends to be politically unchallenging. Actually, there's a lot of shiny art; at this very moment in Chelsea we have a lot of stainless steel. It really couldn't be spelled out any clearer.

JP: I think it tends not to be craft-based either—

NS: The craft base of it is not visible because people hire fabricators to make their art, there's not sort of a hand-made look to the asset-classed work.

WP: I was going to say it comes back to Bushwick; most of the artists can't afford to make that stuff.

AF: But William, you know the first piece of yours that I bought was your greeting cards that you did with Jennifer Dalton; what did I pay for that, 125 dollars? And then I bought just one of the watercolors from that work for a lot more money, though I can't afford you now. So the cards, I never opened the box and they've still got the black ribbon on them, are they of any less value to you as a production? They were 125 dollars for a 200 editions size; is that any less meaningful? Do you feel that my higher priced piece holds a different aesthetic?

WP: At a certain point it does become asset-classed; we can't ignore that anymore. But it's not any less valuable to me. And I find the idea of multiples fascinating. Like, you're selling a certificate, or you're like Thomas Kinkade and you have a thumb print, and you keep it so you can keep printing his thumb on endless editions of these horrible things. But I don't think that because something is of lower value—I want to sell my art for as much as I can within a reasonable realm; it'd be nice to sell something for a lot of money so I could buy a building and not be beholden to the market. But there's this bullshit level where artists can do whatever they want price-wise with their conscience, but once it leaves and goes to auction it's totally out of their hands. That's why Richter is like "shit, the prices are absurd," because it's not his choice anymore. He has no right to say "you can't buy my painting for seventeen-million, that's insane."

JP: I'm going to close it out with Loren.

LM: Someone asked whether there was any kind of an art movement or some kind of aesthetic that was unique to Bushwick, and I was kind of thinking about this the other day. I went inside the Whitney Biennial, and I went to the press opening and I was looking at it and looking at video, and in certain ways, typical of the New York art world, they were paying homage to the Bushwick scene. When I say the "Bushwick scene," you'd be talking about the pathetic kind of crap-on-crap aesthetic, and you're also talking about the aesthetic of capital. Part of it is also the reverse of that, which is people that are making art out of the stuff that people have left on the street because they got booted out of their loft. So I actually felt that a lot of the art that the people at the Whitney were putting out (and I don't think there were any Bushwick artists, maybe one or two) was kind of a reflection of what's happening in Bushwick. It was just very pathetic, crap-on-crap, kind of eccentric. And I know we were talking about artists needing big spaces, a lot of people I know out here don't have big spaces so the art has been scaled down, and a lot of the art galleries aren't huge so you can't show these eight-by-twelve foot paintings everywhere. The other thing is that Bushwick really has kind of re-interested a lot of people in performance. And I think the fact that the Whitney Biennial has like two-thirds or three-quarters of the top floor dedicated to just performance really reflects the fact that there are a lot of performance spaces and a lot of people take performance here in Bushwick very seriously. So that's the way that the art world would like to come out and get Brooklyn performers to come and do that, but it's sort of like "we like what they're doing, but we're going to substitute our politically correct people." But basically it's like sort of Bushwick but not really Bushwick. So that was my impression.

JP: Thank you so much.

Transcribed, edited, and condensed by Mene Ukueberuwa, Rebecca Hecht, and James Panero