Hirschhorn has never shied away from turning global politics into his own personal sleaze. His exhibition some years ago at the Gladstone Gallery called “Superficial Engagement” mixed faux tribal statuary with photographs of corpses in the streets as some kind of commentary on the War on Terror. Or perhaps it was a meditation on the aesthetics of pipe bombs. In either case, the show made a lugubrious fetish out of violence and assaulted the dead by mutilating their bodies a second time in furtherance of a slick Chelsea gallery show.

When Hirschhorn announced his plans to construct, in the courtyard of a Bronx housing project, a “temporary monument” dedicated to Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937), a founder of the Italian Communist party and a patron saint of chic Marxists everywhere, the New York art world let out a collective groan. It does not help that Hirschhorn seems to have learned his English by reading the pages of October magazine. He generally communicates in a self-obsessive hauteur slathered with radicalized special sauce. “I have always understood ‘me’ or ‘I’—which I use often and with no bashfulness,” he writes.

Hirschhorn does not make just “art.” He creates capital-A “Art.” Similarly, his Bronx audiences are not merely other people. They are “the Other.” “I love to encounter the Other through an Idea,” he writes in the Gramsciexhibition brochure. “I love to do it through a mission I give myself and I love to do it through Art.” All of these statements are repeated on the Monument’s website (gramsci-monument.com), which continues the faux-naif schtick by looking as though it was designed in Geo-Cities circa 1995.

Thomas Hirschhorn, Gramsci Monument, 2013; Forest Houses, Bronx, New York; Courtesy Dia Art Foundation; Photo: Romain Lopez

Hirschhorn has a thing for placing “monuments” dedicated to esoteric theorists in underclass locales. Gramsci is the fourth in a series that has included Baruch Spinoza, Gilles Deleuze, and Georges Bataille. One gets the sense that the expeditionary vectors of these comp-lit colonizations are, to him, arbitrary. The residents of “Nychaland,” as some call the project islands of the New York City Housing Authority, are to him interchangeable with the residents of the Red Light District in Amsterdam or with the residents of a French banlieue—all of whom have now received Hirschhorn specials. They are all “the Other.”

In selecting Forest Houses, a project in the Morrisania section of the Bronx, Hirschhorn seems to have deployed all of the top-down metrics of Le Corbusier astride a cement mixer. Hirschhorn knew he wanted to doGramsci in the Bronx. Naturally. What won Hirschhorn over to Forest Houses after a thorough canvassing of the borough’s housing projects, however, was Erik Farmer, the wheelchair-bound President of the Forest Houses Resident Association, who, after hearing the artist’s presentation, asked Hirschhorn if he could borrow a book on Gramsci. That was a tough break for Castle Hill Houses, Soundview Houses, Monroe Houses, Patterson Houses, Bronx River Houses, and Claremont Rehab, the other finalists for the project—or perhaps that should be “the Other” finalists.

It was the book that got Forest Houses the monument, according to Hirschhorn. Farmer also won the golden ticket as the grandee to dole out the many $12-an-hour jobs that Dia commissioned for the Monument’s construction and security (Hispanics complained that only black residents got the gigs, an issue that Dia has now reportedly resolved).

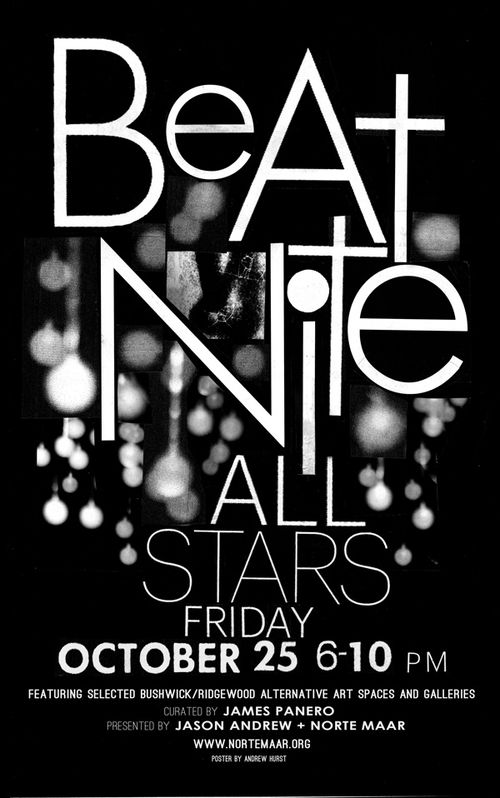

"The point of modernity is to live without illusions, while not becoming disillusioned."—Antonio Gramsci; image: James Panero

What these residents have built, under Hirschhorn’s hard-driving direction, is a shantytown of plywood in the middle of the Forest Houses central green. The structure consists of a spongy, water-logged platform in two sections, accessible by ramps and stairs and connected by a rickety bridge (it is surprising that Dia doesn’t have you sign a liability waiver when setting foot in this accident-deliberately-waiting-to-happen).

Atop the platform are plywood rooms with tarpaulin roofs and signs that indicate each of their functions—a “Radio Studio,” a “Newspaper,” an “Internet Corner,” the “Antonio Lounge,” the “Gramsci Bar.” A Gramsci Museum features relics from Gramsci’s internment at the hands of Italian Fascists, a period of time from 1926 to his death in 1937 that turned out to be incredibly productive for the Communist theorist, resulting in over three-thousand pages of letters and notes that were collected and published soon after the war. A comb, a brush, and a pair of Gramsci’s prison slippers, on loan from the Casa Museo di Antonio Gramsci in Ghilarza and the Fondazione Istituto Gramsci in Rome, are displayed in Plexiglas cases alongside books on Communism, sofas wrapped in packing tape, and a looping film that, at least when I looked at it, featured the face of Joseph Stalin.

Thomas Hirschhorn, Gramsci Monument, 2013; Gramsci Archive and Library; Forest Houses, Bronx, New York; Courtesy Dia Art Foundation; Photo: Romain Lopez

The entire structure, meanwhile, is covered with an accretion of spray-painted agitprop and stapled-up flyers. One poster I saw on arrival featured the cover of the recent Gramsci Monument Newspaper, the project’s paper of record: “<QUOTE OF THE DAY>” it read. “‘The materialist doctrine that men are products of circumstances and upbringing, and that, therefore, changed men are products of other circumstances and changed upbrinding [sic], forgets that it is men that change circumstances and that the educator himself needs educating.’ Karl Marx.”

Similar signs are plastered throughout the structure and generally feature Gramsci’s esoteric Marxist exhortations. “I LIVE, I AM A PARTISAN. THAT IS WHY I HATE THE ONES THAT DON’T TAKE SIDES. I HATE THE INDIFFERENT,” reads one example, spray-painted on a bed sheet by the Monument’s entrance. Here is another: “This distinction between form and content is just heuristic because material forces would be historically inconceivable without form and ideologies would be individual fantasies without material forces.’ (Prison Notebook 7) A.G.” Also prominently displayed are statements from Marcus Steinweg, a German philosopher-in-residence who has been giving daily lectures at the Monument on “Adorno,” “Ontological Poverty,” and “The Uncanny (Heidegger) – The Real (Lacan) – The Outside (Blanchot).” In “What is Art,” Steinweg muses, “Art is pointing out the ontological inconsistency of the world of established consistencies. . . . As transcendence of ontological narcissism art applies the experience of the uncanny. . . . As the experience of the lack of subjectivity art affirms itself as affirmation of a world without beyond.”

Given the barnstorming excitement of these statements, it may be surprising to learn that the Gramsci Monument has not turned into the sleeper hit of the summer. It has also not become a rallying point for Communards or the relics of Occupy Wall Street, even as it presents the Disneyfied version of a radical occupation—a combination of grad-school treehouse and Mr. Toad’s Wild Encampment.

Signage at the Gramsci Monument; image: James Panero

Hirschhorn claims to be a Gramsci fanatic: “My love includes everything coming from him, without exception. I am a ‘Gramsci-Fan.’ As a fan—as every fan—there is no criticism, no distancing, and there is no limit.” Yet one feels that the subject matter of the Gramsci Monument is ancillary, icing on the cake, a good source for quotes and spray-painted murals but, like “the Other,” interchangeable with any number of other subjects and only as important, for Hirschhorn, as the next big public commission. Documenta, Manifesta, Mocumenta, here we come. Even Hirschhorn himself admits: “As with my other monuments to Spinoza, Deleuze, and Bataille, my competence to do the Gramsci Monument in the Bronx does not come from my understanding of Gramsci, but from my understanding of Art in Public Space today.”

The monument’s reduction of Gramsci to sloganeering is regrettable, in that it fails to engage, for or against in any meaningful way, with the profound if not profoundly unsettling ideas that Gramsci put forward. Leszek Kolakowski, in Volume III of Main Currents of Marxism (“The Breakdown”), his masterful 1978 atomization of socialist ideology, calls Gramsci “probably the most original political writer among the post-Lenin generation of Communists.” Through his prison writings, Gramsci articulated “an independent attempt to formulate a Communist ideology” that was not “merely an adaptation of the Leninist schema.” His writings contained a powerful if not altogether coherent “attempt at a Marxist philosophy of culture whose originality and breadth of view cannot be denied.”

Although Gramsci rejected the term, he was also a relativist. “The rightness of an idea is confirmed by, or perhaps actually consists in, the fact that it prevails historically,” Kolakowski explains, “a view irreconcilable with the usual one that truth is truth no matter whether or when it is known, or who regards it as true and in what way . . . it is not clear how he can be acquitted of being a historical relativist.”

What Gramsci’s theory of cultural relativity meant was that, in short, ultimate Revolution could not happen in the Soviet model from the top down. It had to emerge, culturally, from the bottom up. In this formulation, “Workers could only win if they achieved cultural ‘hegemony’ before attaining political power.” Gramsci therefore set about arguing for a “new proletarian culture” that might radicalize at the grassroots level. For this reason, the Gramsci name has been associated with everything from “community organization” to the tenured radicalization of the Academy. The Gramsci strategy has been to Revolutionize culture from within, to influence, if not infect, traditional democratic culture and faith, in his famous phrase, with a “long march through the institutions.”

Thomas Hirschhorn, Gramsci Monument, 2013; Gramsci Bar; Forest Houses, Bronx, New York; Courtesy Dia Art Foundation; Photo: Romain Lopez

Hirschhorn also gets his Gramsci Monument wrong in another profound way. With typical peacockery, he goes out of his way to claim solitary credit for the communally built structure. “I, the artist, am the author of the ‘Gramsci monument.’ I am entirely and completely the author, regarding everything about my work. As author—in Unshared Authorship—I don’t share the responsibility of my own work nor my own understanding of it, that’s why I use the term: ‘Unshared.’ ”

He refuses to see the monument outside of his own world view of “Me” and “Other.” “I never use the terms ‘educational art’ or ‘community art,’ and my work has never had anything to do with ‘relational aesthetics.’ The Other has no specific ties with aesthetics. To address a ‘non-exclusive’ audience means to face reality, failure, unsuccessfulness, the cruelty of disinterest, and the incommensurability of a complex situation. Participation cannot be a goal, participation cannot be an aim, participation can only be a lucky outcome.” In another place, he says, “I am an artist, not a social worker.”

Yet while Hirschhorn professes to see nothing but “Other” when he looks out over the Forest Houses courtyard, his work is much closer to the “relational aesthetics” of Marina Abramovi? or Tino Sehgal than he professes to admit.

Through her trumpeted connections with the pop star Lady Gaga and the rapper Jay Z, Abramovi? has emerged victorious from her MOMA staring contest and grown into an international cultural conglomerate wholly in the service of the celebrity police state. Abramovi? gave us “The Artist is Present.” Now, with Hirschhorn, we have “The Artist is Present in the Bronx,” and the result is ultimately—and entirely in spite of itself—compelling.

Artist Thomas Hirschhorn (left), creator of the Gramsci Monument, sitting at the Gramsci Bar speaking with residents and visitors; image: James Panero

Where the Gramsci Monument succeeds is not in bringing Gramsci to “the Other.” Instead it is in bringing “the Other” to the Bronx. In his interview with The New York Times, Erik Farmer offers a clear explanation of the Monument’s appeal: “There’s nothing cultural here at all. It’s like we’re in a box here, in this neighborhood. We need to get out and find out some things about the world. This is kind of like the world coming to us for a little while.” For Hirschhorn, Farmer says, “this is a work of art. For me, it’s a man-made community center. And if it changes something here, even slightly, well, you know, that’s going in the right direction.”

It is ironic that in this island of a housing project—a city-destroying idea imported from Europe—another European import has re-

introduced a cultural spectacle to reseed some life on the ground. Hirschhorn wants the results all to himself: “I am doing it because I authorize myself to do it. . . . Universality of Art is the condition granting to touch the Other, the Reality and the ‘Truth.’ As an artist, Universality is my belief and my will.” But the Monument works precisely because it no longer belongs to Hirschhorn. On one wall, Hirschhorn has stapled an article from the Village Voice stating the “Top 10 Reasons Why So Few Black Folk Appear Down to Occupy Wall Street.” Yet here, no one seems to care. TheGramsci Monument has not become an international attraction or an agent of radicalization. It has instead become something that the residents of Forest Houses can lay their hands on and call their own.

At the entryway to the “Internet Corner” there is a sign that warns “No Facebook!! If seen on Facebook, you’re getting off the computer.” But the children inside whom I observed were doing just that, if not playing computer games, and they seemed to be enjoying it. The same goes for the kids in the art studio, the busiest room in the facility. Their enjoyment mixed with the laughing of the children playing in the project playground outside, all giving the monument a decidedly homey feel.

The Gramsci Monument has not radicalized the residents of Forest Houses. The residents of Forest Houses have domesticated the Gramsci Monument. This seems especially true for the artist himself. Despite his own off-putting personality, Hirschhorn has clearly been taken by the residents of Forest Houses, and they have been taken by him. This fact gets reflected in the “Resident of the Day” wall and the resident photos that are reproduced in the Gramsci Monument Newspaper. It is also apparent in the way Hirschhorn can be seen interacting with the Monument’s visitors. To his credit, Hirschhorn has been present at the Monument throughout its run, updating the signage on the structure, chatting with visitors at the bar, and, of course, unrolling more packing tape on a regular basis. He is present even as few people show up for his talks. What if you gave a lecture called “Art school by Thomas Hirschhorn 11am to 3pm today. Energy=Yes! Quality=No!,” and nobody came? This is now Hirschhorn’s daily experience.

It may not be art, it certainly is not the art the artist intended, but theGramsci Monument has nevertheless found a place at Forest Houses—in particular for bringing a rich, theory-laced European with a Quixotic, hand-built habitat to these residents’ backyards.

Gramsci Monument: A Work in Public Space by Thomas Hirschhorn is on view at Forest Houses, the Bronx, from July 1 through September 15, 2013.