Centerpiece at the Hispanic Society of America: Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, The Duchess of Alba, 1797; Oil on Canvas, 210.2 x 149.2 cm

THE NEW CRITERION

May 2014

Gallery chronicle

by James Panero

On the Hispanic Society of America and “William Powhida: Overculture,” at Postmasters, New York.

There is something antediluvian about the story of Theodore S. Beardsley Jr., the director of the Hispanic Society of America from 1965 to 1995. What? Never heard of Beardsley’s trove of Spanish art, artifacts, and literature sequestered in an alcazar in Washington Heights? Good, went his reply, and why should you. “We’ve been here since 1904 and one of the things we’ve learned to do is lie low,” Beardsley said to Grace Glueck ofThe New York Times in 1989, “I’ve sat on a lot of boards, and bigness is always worse.”

Founded in 1904, opened in 1908, the Hispanic Society was the first of several institutions to anchor the beaux-arts campus of Audubon Terrace, the great and distinctly American cultural vision of the philanthropist Archer M. Huntington located on 155th Street and Broadway. (I wrote about the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Terrace’s other remaining institution, in last month’s column.) Motivated by a love for Spanish storytelling, Huntington created a jewel-box that was as fanciful as the tales he read, filling it with books, art, and artifacts from Iberian history. He bought masterworks by El Greco, Goya, José de Ribera, Velázquez, and Francisco de Zurbarán along with 800 other paintings, 6,000 watercolors and drawings, 1,000 sculptures, 6,000 decorative objects, 15,000 prints, and 175,000 documentary photographs of Spanish life. Much of this he stuffed into the Society’s main court hall. He ringed a tight second-floor balcony with his most significant paintings, which are still not shown in ideal light. Goya’s Duchess of Alba (1797) greets visitors upon arrival with an hauteur that recalls the work of John Singer Sargent (whose studies from the Prado are included here as well). He also gathered a significant collection of over 250,000 books and manuscripts on the Iberian Peninsula—20,000 printed before 1701, including rare hand-drawn maps of Spanish exploration (a singular example is kept behind a curtain in the Society library) and a first edition of Don Quixote.

The Society’s art, architecture, and sculptural program spoke to the high-minded wonder of Huntington’s vision. Charles P. Huntington, Archer’s cousin, drew up the master plans for the beaux-arts campus and designed the buildings of the Hispanic Society itself (Cass Gilbert and William M. Kendall of McKim, Mead & White were other architects for the site). In the 1920s, the celebrated sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington, Archer’s wife, designed a grand outdoor program, after the site’s orientation was turned east to Broadway, for what was at first a staircase leading up from 166th Street. Here her bronze equestrian statue of El Cid, the medieval Castilian knight, rides beside a monumental relief of Don Quixote. Huntington also commissioned the painter Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida to create a fourteen-painting cycle of “Visions of Spain,” recording regional scenes of Spanish life, which he installed in their own hall in the Society.

Audubon Terrace with The Hispanic Society of America at center.

Yet Glueck’s article, “Major Hispanic Museum Lies Low and Likes It,” was as much about exposing Huntington’s successor’s unreconstructed attitudes towards museum governance as drawing attention to the treasured collection in his trust. Blessed with Huntington’s endowment income and tasked with strict rules about how the institution should be run, Beardsley showed little interest in serving anything more than the founder’s wishes. When it came to donor intent, he was an unreconstructed originalist. There was the issue of loans, for instance. Huntington never wanted his masterworks to leave the building, nor that outside works be shown among the collection, and Beardsley agreed. ‘’We love them,” he said of such restrictions. ‘’You put pieces in jeopardy by moving them around. The whole loan thing is a mixed bag.’’ There was also the library, where Beardsley strictly limited the hours and forbade patrons from making copies. “A lot of our consultation is by mail and telephone,” he explained to Glueck. “We’re much more famous in Madrid than we are here.”

And then there was his approach to fundraising. “We have never blatantly courted donors,” he admitted. “We find it tacky. Mr. Huntington felt it was not very gentlemanly, and until he died if we needed money, he wrote a check.’’ Beardsley refused to publish the names of his board. Even as his endowment dwindled, his curatorial staff shrank in number, and his building was in need of repairs, he had little desire for an infusion of funds. “Our maintenance is slow, but if someone gave me a check for $10 million, I wouldn’t do it faster,” he concluded, “there’s a danger in having too many workmen in the building.”

Given Beardsley’s antiquated ideas, it’s remarkable he lasted as long as he did. Five years after Glueck’s article, reality caught up with him. It was merely chance that, largely after World War II, a Hispanic population settled in the neighborhood around the Hispanic Society. For Beardsley, the only time “town and gown” came together was when they came for him. In 1993, Robin Cembalest published an interview with Beardsley in Art News in which he stated that he didn’t reach out to his local community because they had a “low level of culture.” In the same piece, George S. Moore, a retired chairman of Citibank and the Society’s octogenarian president, blasted the neighborhood as “nontaxpaying slums.” When word of this interview got out, according to Cembalest, protesters gathered to chase the director as he crossed the Terrace courtyard, chanting “Beardsley,racista!” A year later, it was over for Beardsley, and Mitchell Codding, the Society’s current director, was installed.

The main court hall of the Hispanic Society of America. Nicole Bengiveno/The New York Times

It’s easy to mock a figure like Beardsley. Across the cultural world, his notions of museum stewardship, curmudgeonly and narrow, have now been eclipsed by nearly the direct opposite. Today our model of cultural governance looks to reinterpret a founder’s wishes, encapsulate original buildings in new construction, maximize turnstile numbers and revenue, and make fundraising the metric of institutional success, all the while lavishing the administration with six- and seven-figure salaries. Yet with so many institutions, from the New York Public Library to the Museum of Modern Art, now pursuing this destructive extreme, it must be said that the crustiness of Beardsley’s tenure left us an institution that was unspoiled. For now, we can continue to enjoy a free institution as its founder intended while appreciating an artifact of American museology that is nearly untouched.

For an institution as anachronistic as the Hispanic Society, rich in art and artifacts but out of line with contemporary museum standards, the future is never certain. For a time after his arrival, Codding announced his intentions to relocate the Society further downtown. It would have been a move that mirrored the departure of several other of the Terrace’s original inhabitants. In the 1970s the American Geographical Society left for Wisconsin. In the 1990s the Museum of the American Indian went to Washington. In 2008 the American Numismatic Society relocated to downtown Manhattan. For the Hispanic Society, picking up stakes was a predictable idea, but it would have been a disastrous one, curing the institution by killing it. Fortunately, these plans never materialized, and now, it appears, Codding has doubled down on his current location, acquiring an annex from the former American Indian museum and repairing his infrastructure (although he has come under fire for auctioning off a multi-million-dollar coin collection).

The Hispanic Society of America, with original entrance gate facing 166th Street.

Today’s museum directors have a habit of mistaking solutions for problems. The remote setting and idiosyncrasies of the Hispanic Society are not what drive people away. They make the place a wondrous attraction. The challenge is to find a golden path of leadership that understands and nurtures the soul of an institution, rather than carving it out and replacing it. While at the helm of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Philippe de Montebello understood this course better than anyone, and fortunately he has now been serving as an advisor to the Hispanic Society. One of his suggestions, a good one, has been to add the words “museum” and “library” to the Society’s name. Such modest and smart proposals are just what the Society needs to continue broadening its outreach without becoming a community center, a shopping mall, or a blockbusterKunsthalle—and the Society can still do more. Its outward appearance is weedy and uninviting. Whoever heads up its social-media outreach is doing yeoman’s work, but an overhauled website would be nice too. The courtyard is in need of a facelift, and the entryways could use better signage. Frankly, even while walking within Audubon Terrace, I passed by the Society for years without realizing there was a remarkable and free museum just inside those doors. A broader advertising and media campaign would go a long way—along, of course, with a grant for it. So too would further outreach to the local community, which Codding has already initiated (although as an outsider I would welcome a guide to the area’s Hispanic restaurants, such as the delicious and affordable Margot). And why doesn’t the MTA do more to spread the word of this unsung venue, which, after all, is only a subway ride away?

As the dynamics of New York culture are being driven out from the center to the peripheries of the city, 155th Street and Broadway offers a welcome reprieve from the big-money bustle of our more establishment institutions. The adopted son of a railroad baron, Archer M. Huntington assumed that high culture would follow the new subway lines uptown. It may have taken a century longer than he expected, but Audubon Terrace may suddenly find itself in the right place at the right time.

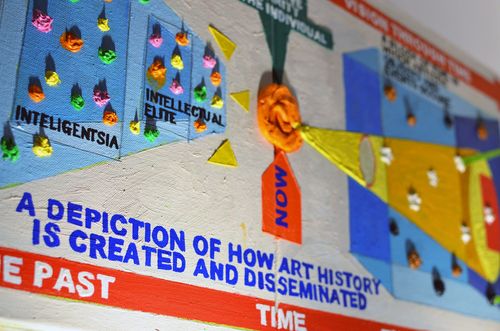

William Powhida, "Overculture," exhibition installation view

One of my most anticipated exhibitions last month, and certainly related to the discussion above, was “Overculture” by William Powhida at Postmasters.1 Powhida mixes information-rich diagrams (also called “Informationism”) with institutional critique. He is famous for his cranky public persona, which he widely broadcasts through Twitter. For a younger man, he has cultivated a surprisingly high level of dyspepsia and bile. Yet his work succeeds for two very obvious reasons: the humorous intelligence of his criticism and the craft of his draftsmanship. Both aspects were on display at Postmasters. They were even knowingly divided into two distinct sections. On one side, there were the hand-drawn lists of art-world quibbles for which he is best known. Some were drafted to look like they were scribbled on enormous lined spiral paper, such as How To Try To BeOK With The Contemporary Art Market and How To Make An Auction Ready-Made (both 2014). Others riffed on classic diagrams of art history. The best example took the branching tree motif from Ad Reinhardt’s How to Look at Modern Art in America from 1946 and turned it into How to Look @ The Contemporary Art-Industrial Complex in America. In Powhida’s take, name-brand artists are the big leaves growing from the trunk of “Auctions and Big Box Franchises,” while a smaller branch of emerging and mid-level artists has been eaten away by a beaver labeled “rent,” and the smallest branch for “non-profit artist run alternatives” has been shot through and bandaged up while waving a white flag labeled “culture war.”

William Powhida, How To Look @ The Contemporary Art-Industrial Complex In America, 2014; graphite on paper, 31 x 23 inches

The other half of Powhida’s exhibition sublimated his criticism in his craft. The painted spiral-bound sheets went abstract and blank, or they were turned into sculptures of metal that resembled God-sized crumpled notebook pages, created with remarkable verisimilitude. A final work at first looked like nothing but screws in the wall and leveling lines, as though a piece had been removed. But a closer inspection revealed it to be trompe l’oeil, drawn directly on gallery drywall. Had Powhida sold, or had he sold out?

The self-awareness of this show and its high level of skill left me with a sense for Powhida that was ultimately more profound and somber than comic. The nature of his criticism reminded me that our cultural problems are far more endemic than we like to admit. A critic of the left, he would find common ground in much of what appears in these pages. The fact is, our cultural establishment is now unswayed by criticisms shared across the political spectrum. Which leaves the rest of us tilting at windmills.

1 “William Powhida: Overculture” was on view at Postmasters, New York, from March 15 through April 19, 2014.