The Joan of Arc Memorial in Riverside Park today. via

THE NEW CRITERION

January 2016

Gallery Chronicle

by James Panero

On the Joan of Arc Memorial in Riverside Park.

Early last month, New Yorkers had a new opportunity to revisit an old monument. On December 6, the Joan of Arc Memorial, on Ninety-third Street and Riverside Drive, turned 100 years old. As you might expect, the occasion did not make national news. We live in a time increasingly overwhelmed by the present moment, suspicious if not outright hostile to the symbols of history. This birthday for a monument of bronze and stone, unmoved by current fashion, could have gone completely unnoticed. But three days earlier, an assembly of local grandees, historians, and neighbors (of which I am one) came together in the park’s sculpture precinct to honor the centenary with remarks and the laying of a ceremonial wreath, just as had been done a century ago at the dedication. The celebration brought worthy attention to this moving statue and its remarkable creator, the sculptor Anna Vaughn Hyatt Huntington (1876–1973)—as well as to the volunteers and organizations that quietly care for the work and the surrounding park, in particular the Riverside Park Conservancy and the tenders who volunteer their weekends to maintain the area. The ceremony also welcomed France’s Consul General to the site just three weeks after the terrorist attacks in Paris, giving the event a tragic poignancy. Against the news of the world, the occasion offered a chance to reflect on the art and architecture of historical monuments that stand increasingly in defiance of the dictates of the present moment, and what the future may hold for these reminders of the past.

Like all of the thousand-plus historical monuments in New York City parks, which include some three hundred major works in what is one of the world’s most impressive and unsung public galleries, the Joan of Arc Memorial has had its own unique and now largely forgotten past.

On the eve of the First World War, a public-minded organization calling itself the Joan of Arc Sculpture Committee in the City of New York, led by the philanthropist J. Sanford Saltus and the mineralogist George Frederick Kunz, set about honoring the Franco-American alliance and America’s oldest ally by commissioning a monument to the Maid of Orléans, the quincentenary of whose birth was celebrated on January 6, 1912. The site selected was a rise along what is now known as Joan of Arc island, one of the slivers of green space delineated in Frederick Law Olmsted’s original 1875 park plan by the separation of Riverside Drive and the residential access road to the east.

At the time, the City Beautiful movement was transforming the development of Riverside Park into a promenade of monuments and memorials. Even without a master plan for the sites, Olmsted’s elevated and winding Riverside Drive, which broke from the 1811 street grid to follow the contours of the Hudson highlands, was ideally suited for such monumental works, with sloping sightlines that were framed by the Hudson River on one side and the grand residences and apartment buildings on the other. Then as now, most prominent, at West 122nd Street, is the General Grant National Memorial, the 1897 tomb modeled after the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus and Napoleon’s tomb at Les Invalides (as well as inspiration for the riddle of who is buried therein). The 1902 Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument at West Eighty-ninth Street, modeled after the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens, serves as a southern bookend to Grant’s Tomb (for which it is often confused). Joan of Arc is one of the half-dozen major monuments located on the heights of the drive between the two, an assembly that also includes the Firemen’s Memorial and monuments to Samuel J. Tilden, Louis Kossuth, and Franz Sigel.

According to Anne Higonnet, a professor of art history at Barnard College who mounted an exhibition of Huntington’s art two years ago, the selection of this unknown female sculptor for the memorial was as radical as her female subject matter. Huntington’s father, Alpheus Hyatt, was an animal scientist, a professor of zoology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Boston University. Inspired by the community of naturalists that surrounded her childhood upbringing in Cambridge, Huntington launched her artistic career at the turn of the century as an animal sculptor, in particular an equine sculptor, producing tiny works on commission. In New York, she passed through the Arts Students League and the studio of Gutzon Borglum, the sculptor of Mount Rushmore, while creating studies on site at the Bronx Zoo. She then moved to Paris and dedicated herself in 1909 to the subject of Joan of Arc, the French hero and martyr of the Hundred Years’ War, who was beatified that year.

Gathering a ton of clay in a Paris studio, Huntington worked for four months nonstop. She applied her zoological expertise to the mass and flesh of Joan’s horse, which she modeled on a heavy Percheron used for wagon deliveries, lent to Huntington by the stable of the Magasin du Louvre. Huntington imagined Joan riding a workhorse that, even at rest, bristles with muscles and vascularity, standing with a front leg raised over an impressionistic ground of licked abstract form.

For the figure of Joan, little is known of the historical teenager, so Huntington drew on more current literary accounts, such as the work of the French romantic poet Alphonse de Lamartine and Mark Twain’s Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, published in 1896 under the pseudonym Sieur Louis de Conte. Huntington chose to emphasize Joan’s spiritual devotion, which infused her personality even during her military campaigns. “It was only her mental attitude, her religious fervor,” Huntington explained, “that enabled her to endure so much physically, to march three or four days with almost no sleep, to withstand cold and rain. That is how I thought of her and tried to model her.”

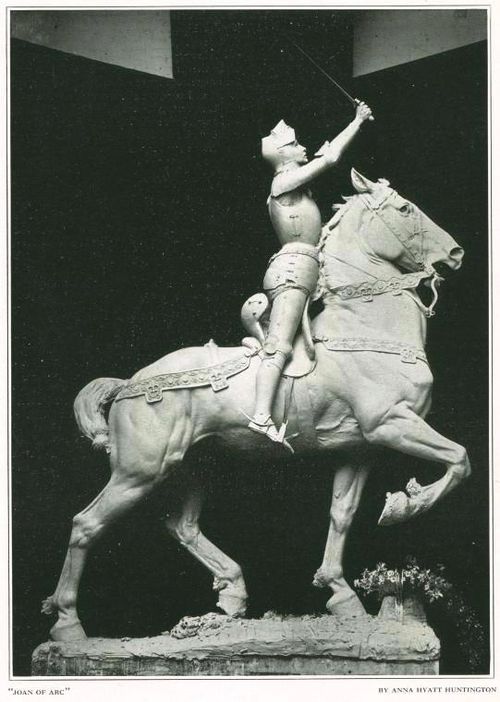

Huntington's plaster cast of Joan of Arc (ca. 1910). via

Huntington placed Joan on her horse rising out of her stirrups, holding her sword skyward in divine revelation. To gather the historical accuracy of Joan’s armor, Huntington says she consulted Dr. Bashford Dean, the Metropolitan Museum’s expert on arms and armor. (Or perhaps not: Higonnet believes her research may have uncovered evidence to the contrary, since the armor was designed before Huntington’s return from Paris to New York. The rivets and articulation of Joan’s armor may have come out of Huntington’s imagination as much as the Met’s permanent collection.)

When she submitted the plaster cast of her clay model to the Paris Salon of 1910, the jurors at first refused to believe a women had completed the sculpture on her own. Yet one of the reasons Huntington had refused visitors to her studio was to convince the Salon that she had, in fact, made the work herself, and she eventually received the Jury’s prestigious Honorable Mention.

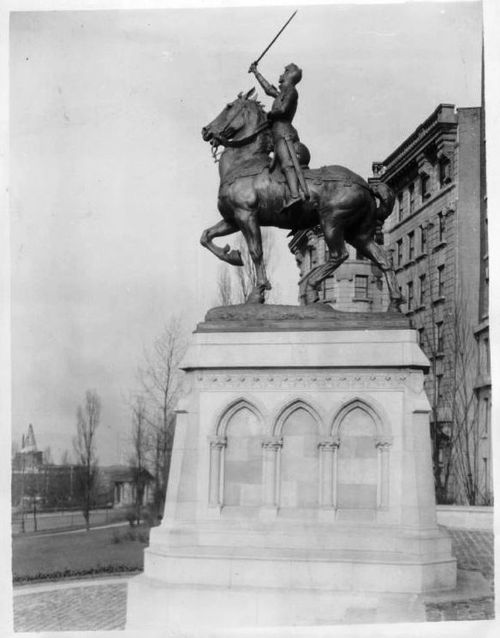

When the Joan of Arc Statue Committee considered models for their monument two years later, they selected Huntington’s—meaning that New York’s first public statue of a historical woman was also created by a woman. Over the next three years, Huntington reworked her Paris Salon model up to one-and-a-quarter life size. The architect John Van Pelt landscaped the elevated site on Riverside Drive and designed the statue’s gothic pedestal. Stones taken from Joan’s cell at Rouen, as well as a fragment of a pilaster from the Cathedral at Reims, where Charles VII was crowned, were worked into Van Pelt’s design. Symbolically, the figure of Joan rises out of her prison while building the foundation for the coronation of the French king.

After it was unveiled on December 6, 1915, amid a crowd of thousands lining Riverside Drive, the statue of Joan made Huntington’s artistic reputation. Replicas of the statue were subsequently created: for Blois, France; Gloucester, Massachusetts; San Francisco, California; and Quebec, Canada. In 1922 Huntington was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. A year later, she married the great cultural philanthropist Archer Huntington, leading to her Spanish equestrian sculptures—the freestanding knight El Cid and bas-reliefs of Don Quixote and Boabdil—that now adorn Huntington’s Hispanic Society and his cultural campus of Audubon Terrace at 155th Street and Broadway. An interest in more recent Hispanic history also led to Huntington’s final major work, the equestrian statue of the Cuban nationalist José Martí on Central Park South, which she created at age eighty-two and dedicated in 1965.

Joan of Arc in Riverside Park soon after dedication. via

The present is not necessarily kind to the monumental past represented by the aspirations of this memorial to Joan of Arc. As the public’s interest in the city’s classical art and architecture has waxed and waned, the importance of this statue, as well as the sculptor behind it, has been eclipsed. Today a campaign for preservation and upkeep, represented by the great civic associations such as New York’s conservancies that have brought parks back from the brink, must still make a case against the tide of “the new” and more pressing political distractions. While the Grand Marnier Foundation supported a major restoration of the Joan of Arc statue in 1987, for example, the sculpture’s grounds remain overgrown, with pavement in need of repair.

More generally, such monuments also face an existential threat. It is is doubtful that a similar monument could be built today, since little agreement could be reached over its design or its meaning. Just look to the drawn-out catastrophe of Frank Gehry’s postmodernist memorial to Dwight D. Eisenhower, proposed for the National Mall. Joan of Arc is now a polarizing historical figure in France, adopted as a symbol by nationalists, and shunned by the internationalist Left.

The specter of worldwide vandalism brought about by the iconoclastic fever of political Islam is one that I documented in “The Vengeance of the Vandals,” my essay for these pages last month. A similar impulse, acted upon to lesser degrees, infuses much of contemporary political culture. In New York, an alarming precedent was set in 1955, when Charles Albert Lopez’s statue Mohammed was removed from the pantheon of lawgivers on James Brown Lord’s 1899 Appellate Division Courthouse of New York State, another City Beautiful design, on Madison Avenue and Twenty-fifth Street, after protests from Muslim nations.

For those who see history as a series of injustices, monuments now represent the embodiment of those grievances. When public works lose their didactic function, contemporary culture, seeing little value in their historical or artistic importance, abandons or destroys them. For this very reason, George Washington regretted the destruction of the leaden statue of George III, pulled down by a mob from its pedestal on Bowling Green in lower Manhattan at the start of the Revolutionary War. From the Buddhas of Bamiyan to statues of John C. Calhoun, monuments today must justify their continued existence. Even when a new and worthy monument is proposed, the pitch today is based not on the merits of the subject matter but on the injustices of what already exists. A worthy proposal, for example, to build a monument to women’s suffrage featuring Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton at Central Park West and Seventy-seventh Street has largely been based on mocking and attacking the “bronze patriarchy” of the Park’s existing statues, embodied by its acerbic URL, centralparkwherearethewomen.org. NYC Parks Commissioner Mitchell J. Silver has spoken in support of the proposal for similar, politicized reasons, claiming the mayor’s “administration is fully committed to promoting gender equity across New York City—and that includes our parks.”

Given this commitment to equity, even over our park’s historical statuary, the Joan of Arc Memorial may avoid being burnt at the stake of political dictates longer than others. But what happens if an atheist takes offence at the saintly Joan, or an Englishman finds grievance in her jingoistic French militarism? Not even Joan of Arc faced an adversary as fierce as our censorious contemporary culture.