THE NEW CRITERION, February 2020

On “The Expressionist Legacy” at Galerie St. Etienne; “Depicting Duchamp: Portraits of Marcel Duchamp and/or Rrose Sélavy” at Francis M. Naumann Fine Art; “Gabriele Evertz: Exaltation” at Minus Space; “Rob de Oude: Light of Day” at McKenzie Fine Art; and “Eric Brown: Longhand” at Theodore:Art.

The declining fortunes of all but the biggest New York galleries continue to have a chilling effect on the world of art. By nurturing artists, cultivating collectors, and opening their doors to all, galleries write the first drafts of art history. New York has been spoiled with such an abundance of great galleries, and for so long, that I imagine we thought they would always be around. Now not a month goes by without another closing, or downsizing, or shifting to private sales, or some other form of retreat from the public square.

The reasons put forth for these changes are many—the globalization of the art market, the rise of the auction houses, and the burden of the art fairs are but a few. Yet I suspect the answer goes deeper, to major shifts in our sociological and visual experience. Much as the rise of online shopping has emptied out Main Street, it could be that a virtual world experienced through digital screens, among many other effects, is pushing the real-world galleries off of Fifty-seventh Street. That gamified, toxified, blue-light mirror in our hands, otherwise known as our smartphone, through its dazzling presentism blinds us to the light of history. A day will come when we will look back on these devices, now caressed like idols in the fingers of nearly every man, woman, and child, as we do a pack of cigarettes. Until then, blink before it’s too late.

This past fall, Galerie St. Etienne, the oldest gallery in the United States dedicated to Austrian and German Expressionism, announced its transition from a commercial enterprise to a non-profit foundation. “Either pursue scholarship or commerce,” declared Jane Kallir, the gallery’s director. “The two don’t work in tandem the way they once did.” Founded in New York in 1939 by Otto Kallir, Jane’s grandfather, this institution has roots going back to Vienna, where in 1923 Otto began a gallery for new art called, appropriately, Neue Galerie. If the name sounds familiar, that’s because Ronald Lauder named his New York museum after Kallir’s first influential home of the Vienna Secession.

Egon Schiele, Portrait of Dr. Erwin von Graff, 1910, Oil, gouache, and charcoal on canvas, Private collection, courtesy Neue Galerie, New York.

In exile in New York, over many decades, Otto Kallir built the market for the modern art of pre-war German-speaking Europe. In a city more enamored with the École de Paris than the Wiener Sezession, that wasn’t always an easy sell. “During the gallery’s early years, Austrian artists like Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt were completely unknown here,” Jane Kallir wrote in these pages in 2011. “We couldn’t give Schiele’s work away.” Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, even turned down the donation of Schiele’s Portrait of an Old Man (Johann Harms) (1916), which Otto Kallir then gave to the Guggenheim Museum.

By the time of Otto Kallir’s death in 1978, the opposite had become true. The reputation of Austrian and German modernism was ascendant. As Hilton Kramer wrote of Galerie St. Etienne in 1981, “Certain aspects of the modern art of Austria are nowadays so much admired—and in some quarters, indeed, so chic—that an entire generation has come of age on this side of the Atlantic with no memory of the obscurity that once surrounded its great achievements.”

Earlier exhibitions tied to the gallery’s eightieth year recognized the role of its directors, in particular Hildegard Bachert, who died last year at age ninety-eight and launched the unexpected late career of Grandma Moses. Now, for its final exhibition, Galerie St. Etienne has mounted a survey on “The Expressionist Legacy,” with a selection of over fifty works by Max Beckmann, Lovis Corinth, Otto Dix, Richard Gerstl, Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Marie-Louise Motesiczky, and Egon Schiele, befitting the gallery’s history in the establishment of their stateside legacy.1

For the city that gave birth to Abstract Expressionism, the legacy of German Expressionism should be an easy fit. Yet this art remains uneasy, even forbidding, so much so that its manners and mores can still cause a stir. The Neue Galerie’s excellent recent survey of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, reviewed in these pages last month by Karen Wilkin, attributed Kirchner’s acidic colors, in part, to the rise of artificial illumination. Kirchner’s rotting pinks and gangrenous greens reflected the preternatural arc-lamps and limelights of the Dresden stage and the Berlin street. In contrast, the selection now at St. Etienne reveals what happens to Expressionism when the lights go down and the colors fade away. These anxious paintings and drawings can seem even more ominous in the dark of day than the light of night.

For all of its flesh, the mangled eroticism of Kokoschka’s watercolors ultimately seems desiccated and burned-over. Schiele’s bloody, bony Portrait of Dr. Erwin von Graff (1910) looks flayed of skin, while his dry landscapes maintain the chromatic range of tobacco juice. Corinth, a generation older than Schiele but here represented by his late work following World War I, found expression in his earlier Impressionism. His Garden Terrace on the Walchensee (1923) is an agitated torrent of mud wiped across the painting’s surface. Gerstl’s pen-and-ink self-portraits from 1907 are likewise dripping ghosts nearly sprayed into oblivion. Klimt is also well represented here, with decorated surfaces that subsume their subjects. Uptown from St. Etienne, in Klimt’s bedazzled Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (1907), the painting brought to the Neue Gallerie from Vienna in a famous case of Nazi-era restitution, the “woman in gold” drowns in her opulent splendor. So too for Klimt’s Baby (Cradle) (1917–18), now at St. Etienne, who is storm-tossed in a sea of bunting. That painting is here on loan from Washington’s National Gallery of Art. It was given in 1978 as a gift of Otto and Franciska Kallir—one of the many bequests given to our country by this family gallery.

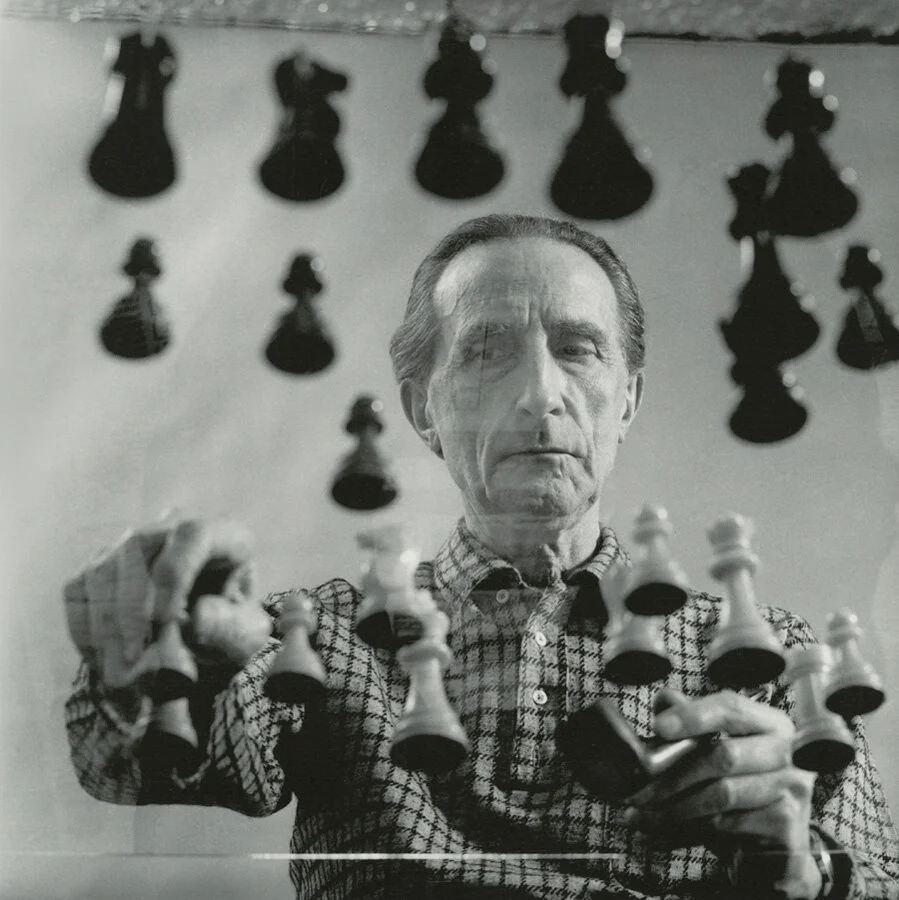

Arnold Rosenberg, Marcel Duchamp Playing Chess on a Sheet of Glass, 1958.

Just downstairs from St. Etienne at 24 West Fifty-seventh Street, Francis M. Naumann Fine Art has mounted its own final exhibition. A scholar of Duchamp and the gallery’s eponymous owner, Naumann in 1994 wrote the definitive book New York Dada 1915–25. For two decades the exhibition program of his small gallery has gone for substance over style, even (especially) in the case of the often substanceless work of the idea-driven avant-garde of the early twentieth century.

Duchampianism long ago turned into that dead albatross around the neck of contemporary art, cursing us with yet another overpriced banana duct-taped for our sins to the gallery wall. Yet, curiously, Duchamp himself, that old slippery banana, reserved his final pratfalls, withdrawing in his later years to play chess and never benefiting from the spume churned up in his wake. “It is ironic that work by contemporary artists sells for more than work by the artists who inspired them,” Naumann notes, citing Jeff Koons in particular. So even Duchamp, that artist who, for better and worse, saw the future, is left to the dustbin (and urinal) of history. “There are fewer and fewer collectors of twentieth-century art,” says Naumann, “because the younger generation wishes to identify with the art of their times and feels that the art of the past is—by definition—passé.”

For his final show, Naumann has gathered together “Portraits of Marcel Duchamp and/or Rrose Sélavy.”2 Duchamp’s punning, cross-dressing alter ego reveals how this artist foresaw the free-floating identity crisis of our present day. We are (mostly) all Duchampians now.

The many artists gathered for this tribute, some old and some new, capture the shape-shifting artist in oblique and often inventive ways that reveal much about the original Duchampian. Inspired by Duchamp’s Self-Portrait in Profile (1959), a silhouette of negative space made of torn paper on velvet, shadows here illuminate more than light. An ingenious wall sculpture by Larry Kagan, Duchamp Self-Portrait in Profile (2015), turns a steel abstraction, when lit just so, into a shadow of a shadow. Tom Shannon’s Mon Key (2003), which at first resembles nothing more than the key to a filing cabinet, likewise betrays the signature profile when hanging against the wall. The selection of historic photographs of the artist are especially compelling, as they try to uncover something in his Sphinx-like visage. Arnold Rosenberg and Victor Obsatz each used multiple exposures to capture the chimeric artist. In the Oculist Witness (Marcel Duchamp) (1967), Richard Hamilton depicts the artist through a pane of glass on which he has superimposed a collage of silver metallized polyester. Rosenberg’s Marcel Duchamp Playing Chess on a Sheet of Glass (1958) likewise looks at the artist through glass, here mid-move from a perspective below the transparent gameboard. Before his death, Duchamp became a competitive “master” chess player. He was known (as might be expected) for radical opening gambits that kept his endgame deep in the shadows.

Gabriele Evertz, ZimZum, 2019, Acrylic on canvas, Minus Space.

Despite the closings, many galleries are still thriving, or at the very least mounting exceptional contemporary shows. Gabriele Evertz, a scholar of color, uses contrasting and conflicting stripes of super-saturated pigments to dazzle the eye and accelerate the pulse. Her large works now at Brooklyn’s Minus Space may just be paint on canvas, but their effect in person is dizzying and disorienting as the eye looks up and down for solid ground.3 Colors melt into stripes of gray as surfaces seem to ripple in and out. For this current exhibition, Evertz relies on a combination of formula and improvisation to arrive at her final compositions. I especially enjoyed the lighter ones, where fields of white serve to cool her radiant color temperatures.

Rob de Oude, Feature Focus, 2019, Oil on canvas, McKenzie Fine Art.

On the Lower East Side, the Netherlands-born, Brooklyn-based artist Rob de Oude weaves together strands of paint into textile-like wonders. After years of working in moiré patterns—the effects that emerge from conflicting arrangements of lines—de Oude now uses subtle variations in color and washes of tone to create squared-off compositions that seem anything but linear. Now in his first solo show at McKenzie Fine Art, on New York’s Lower East Side, rather than radiate out, light appears to glow from beneath and illuminate his designs from within.4 Through an intensity of surface rigor, which he achieves by working with the help of a self-made jig, de Oude finds depth in his penetrating kaleidoscopic effects.

Eric Brown, The Mystic, 2019, Oil on canvas, Theodore:Art.

Meanwhile, in Bushwick, the hard-edge abstractions of Eric Brown have a softer side. Last month, in “Longhand,” his second solo exhibition at Theodore:Art, Brown’s intimate designs on paper and canvas were stitched together in lines of acrylic and oil.5

As the one-time co-owner of Tibor de Nagy Gallery who has left the commercial world to become an artist and seminarian, Brown works by feel. Through a meditative touch, simple patterns belie deeper complexities and find variations across shapes and materials. The handmade quality of these minimalist forms resonate with a casual outer-borough aesthetic. They also bear Brown’s sensitive signature style, now written out in “longhand.”

Against the mesmerizing absorption of our digital world, here are exhibitions that remind us just what analog art can do.

1 “The Expressionist Legacy” opened at Galerie St. Etienne, New York, on October 22, 2019, and remains on view through February 29, 2020.

2 “Depicting Duchamp: Portraits of Marcel Duchamp and/or Rrose Sélavy” opened at Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, New York, on January 10 and remains on view through February 28, 2020.

3 “Gabriele Evertz: Exaltation” opened at Minus Space, Brooklyn, on January 11 and remains on view through February 29, 2020.

4 “Rob de Oude: Light of Day” opened at McKenzie Fine Art, New York, on January 10 and remains on view through February 16, 2020.

5 “Eric Brown: Longhand” was on view at Theodore:Art, Brooklyn, from December 13, 2019, through January 26, 2020.