THE NEW CRITERION, April 2020

On the neglected Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Riverside Park.

Just down the street from my apartment, on the West Side of Manhattan, is a memorial of memorials. The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, at Riverside Drive and Eighty-ninth Street, is one of those veterans of the city landscape that has waged a long war against the forces of ruin. Now, once again, the monument finds itself in a pitched battle over its own survival. The mortar of the structure has eroded away. Rainwater runs through its marble interior. Metal flashing dangles off its cornices. Weeds grow out of its cracked façade. A chain-link fence surrounds the memorial tower and invites further mischief. Young men dash around the enclosure to deface the stonework—something I saw firsthand walking by the other afternoon. They know they have it to themselves.

Some fifteen years ago, in the city’s previous administration, the then–Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe elevated this monument’s aging public promenade from an overgrown asphalt jungle into an appropriate civic space. Yet the monument’s tower has not undergone a major overhaul since 1961. Those repairs may cost $35 million. The city says it has other priorities.

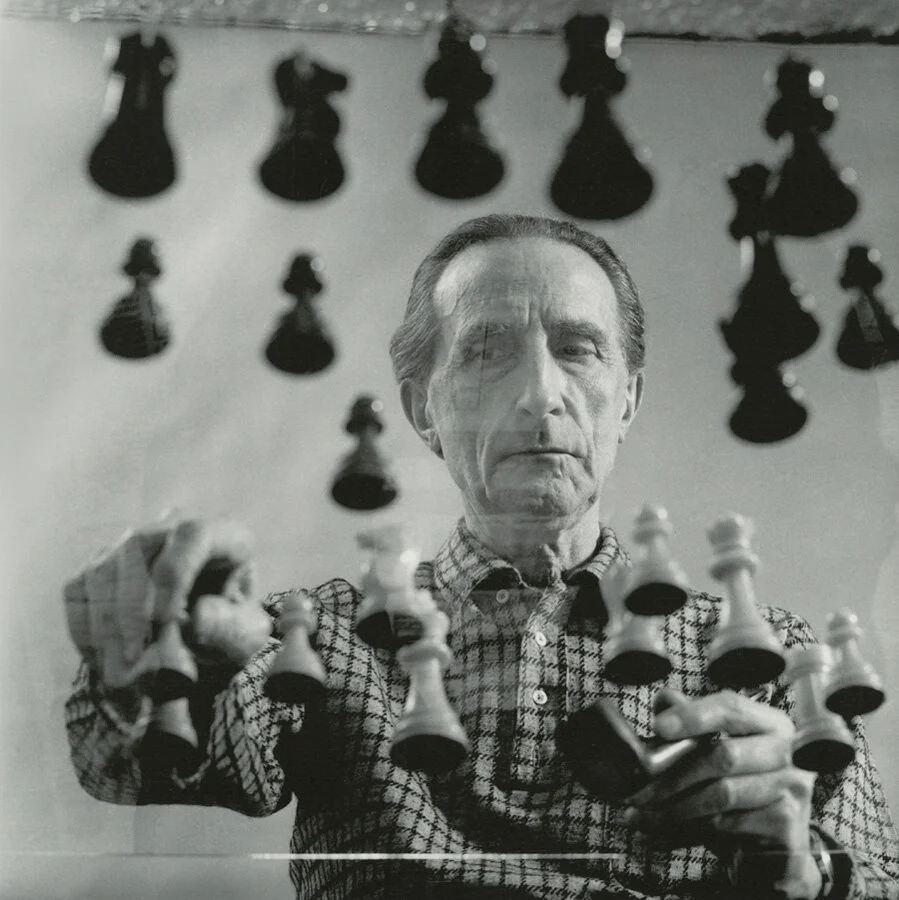

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument. Photo by the author.

You might think that such a monument, a city and state landmark of national historical importance, would take top priority. Since its dedication on Memorial Day in 1902, this Greek Revival temple has honored the Union sacrifices of the Civil War. It has also served as a focus for all of New York’s wartime remembrances. President Theodore Roosevelt officiated over its opening day as veterans of the Civil War paraded up Riverside Drive, thirty-seven years after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. A seventy-four-foot-long American flag, the largest to that date, covered the ten-story tower before it was unveiled. “The memories that hover around it,” Mayor Seth Low declared at its opening ceremony, “already clothe it with a light that makes it sacred to the eye.”

The same light still shines over it today. On a promontory overlooking the Hudson River, even in its neglected state the monument can glow like a rocket as the western sun sets behind it. Twelve Corinthian columns, thirty-six feet high and arranged around an inner marble drum, give its finialed crown of eagles and cartouches a sense of lift. Its ringed base, in smooth stone, adds a compressive and centripetal force.

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument. Photo by the author.

Surrounded by a complex series of terraces, stairs, benches, and plazas, the monument provides various precincts for gathering and ceremony. To the west, centered on a flagpole nearly as tall as the monument itself, a stairway leads in the direction of the river. At one time, these stairs were meant to connect this sailors’ shrine to the waterline. To the north, a lower platform that follows the contours of the natural plateau provides a tight perspective for more personal remembrance. To the south, the semicircular arms of an open and low-stepped quadrangle draw in observants who arrive up the Drive—a curving road that straightens to provide an unobstructed approach to this battery-like promontory, which includes the silenced cannon and cannonballs of 1865.

The monument stands as one of the finest examples of the City Beautiful movement, which populated New York with statues and memorials at the turn of the last century. Charles and Arthur Stoughton, brothers who trained at the École des Beaux-Arts, won the competition with the white marble design, called the “temple of fame,” to serve as the southern bookend for the General Grant National Memorial, completed five years earlier at 122nd Street and based on the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus and the Dôme des Invalides. For the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, Stoughton & Stoughton adapted the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens, a sort of music trophy featuring the myth of Dionysus and the first to use free-standing outdoor Corinthian columns, for a new sober purpose. Paul E. M. DuBoy, the architect of the Ansonia apartment building at Seventy-third Street, designed its sculptural program.

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, pictured during a naval review in 1945.

The monument’s public precincts pay tribute to the Civil War service of New York’s volunteer regiments, with the names of battles and generals listed on the surrounding plinths. Its monumental tower honors the memory of their fallen brothers in arms. A single bronze doorway, topped with an eagle and the words in memoriam, leads into a tall inner sanctum of sculptural niches and ethereal light.

A few years ago, I may have been one of the final people to enter this solemn and spectral space. For decades the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument Association, a volunteer group working with the Riverside Park Conservancy, has organized the monument’s Memorial Day tribute and opened its door to the public for that one day of the year. This community group is among many organizations that has quietly restored and championed Riverside Park’s monuments, memorials, and gardens (see my “Gallery chronicle” of January 2016 for the history of the nearby Joan of Arc Memorial).

Yet for recent tributes, the chain-link fence has had to serve as the backdrop. Without urgent repairs, the monument is now at risk of demolition. As the Riverside Park Conservancy again presses its case, City Hall indeed has had other priorities. As historical structures have been left to ruin, the administration of Bill de Blasio, fresh off his stumblebum presidential run, has pursued an extensive program of cultural grievance and redress. In part this has meant denigrating the city’s past and even toppling memorials in public displays of desecration. In this space in September 2018, I wrote about the removal of one Central Park monument, of J. Marion Sims, a doctor who revolutionized gynecology by developing a surgical cure for a serious complication of birth, but whose practice in the antebellum South has caused his reputation to be denounced by racial activists. For the mayor, such removals, motivated by political bullying rather than historical nuance, were but the pretext for the next campaign: the installation of new leftist monuments throughout the city. At the center of this radical initiative is not just the mayor himself but also his wife, Chirlane McCray, a Madame Mao of New York politics with her own designs on city-wide office.

Our fractious times have not been kind to even the most seemingly innocuous efforts at new memorialization. A well-funded private initiative to mark the centenary of the Nineteenth Amendment saw fit to attack what it called the “bronze patriarchy” of city monuments to get out the vote for its monument to women’s suffrage. The rhetoric at monumentalwomen.org ridiculed Central Park’s historical markers and played the gender card, only to be trumped by the race card. After the classical sculptor Meredith Bergmann worked up a depiction of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, The New York Times asked in a headline, “Is a Planned Monument to Women’s Rights Racist?” A columnist denounced the “explicit prejudices” of the two historical figures “that erased the participation of black women in the movement.” Then, when a depiction of Sojourner Truth was added to the tableau, twenty academics objected in a letter that the new arrangement whitewashed the racist politics of the white suffragists, who “treated black intelligence and capability in a manner that Truth opposed.”

A similar circus has surrounded efforts to replace the toppled statue of Sims, at Fifth Avenue and 103rd Street, with a new counter-monument. After a seven-hour meeting last fall at the Museum of the City of New York, a city panel selected the sculptor Simone Leigh, an artist whose work has appeared at the Guggenheim and Whitney museums and along the High Line, for a racial riff on Manet’s Olympia called After Anarcha, Lucy, Betsey, Henrietta, Laure, and Anonymous—so named for Sims’s enslaved patients. At the announcement, community activists shouted down this selection over the work of Vinnie Bagwell, a local favorite, whose Victory Beyond Sims proposed a less avant-garde sculptural figure. Tom Finkelpearl, the city’s then–Cultural Commissioner, scrambled to address the protest, and Leigh withdrew her design.

The next figure to go down was Finkelpearl himself. Last fall the city put out a public ballot asking for women who should be memorialized as part of its “She Built nyc” initiative. The popular winner, by a wide margin, was Frances Xavier Cabrini (1850–1917). Known to New Yorkers as Mother Cabrini, this heroic nun fought for immigrant health, founded the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and became the first American citizen to be canonized in the Roman Catholic Church.

Mother Cabrini was indeed a woman who “built nyc,” just not the right kind of woman for Chirlane McCray, the unelected executive of her husband’s $10 million sculptural initiative. In the political storm that followed, the actor Chazz Palminteri accused McCray of racism for ignoring a worthy white candidate, de Blasio demanded an apology from the Bronx actor, Governor Cuomo stepped in to say he would memorialize Cabrini himself, and Finkelpearl lost his job in the kerfuffle with the mayor’s family.

The “nomination process was never intended to be a popularity contest,” McCray said in response. It turns out it was never exclusively meant to memorialize women at all, as the First Lady advanced two transvestite figures to take Mother Cabrini’s place. Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera were individuals on the outer fringes of the city’s cultural life. Both started out as prostitutes on Forty-second Street. After founding a group called Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, each descended into mental illness and substance abuse. Johnson’s body was pulled from the Hudson River near Christopher Street, while Rivera succumbed to liver cancer living at a shelter called Transy House.

The extremis of these sad individuals is precisely what appeals to the ever more absurdist politics of identity and representation. Mother Cabrini will have to wait as McCray pushes for a $750,000 memorial to the two drag queen activists. “The lgbtq movement was portrayed very much as a white, gay male movement,” she declares. “This monument counters that trend of whitewashing the history.”

The she of She Built nyc is ultimately New York’s current First Lady, who will not stop at using city funds to memorialize her own political hubris. Her sculptural initiative is but a small representation of her mismanagement of city affairs. For example, as she now organizes her fourth exhibition at Gracie Mansion, this one called “Catalyst: Art and Social Justice,” which opened in February, the city has seen little justice done to a $1 billion mental health initiative, called ThriveNYC, that has languished under her stewardship.

Such machinations will do little to save a monument that, one might say, memorializes our country’s greatest act of “social justice.” America’s deadliest conflict, after all, was the war that ended the country’s acceptance of chattel slavery. This historical reality is what makes the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument so problematic in today’s political climate. In a culture obsessed over America’s “structural racism” through such initiatives as the New York Times’s bogus “1619 Project,” a monument that memorializes the nation’s most anti-racist struggle complicates facile politicized narratives. Rather than remembering, the point now is forgetting, and neglecting, our history in metal and stone.