THE SPECTATOR USA

From the Baths of Caracalla to the Baths of Tenth Street

I miss my shvitz. At least once a week before the shutdown, I went to the Russian & Turkish Baths on 10th Street in Manhattan’s East Village. I saw it as my connection to the ancients. Here was a tiny remnant of classical bath culture surviving in the modern city. Or so I liked to believe. Like much else in New York, I now sweat for its return.

Back when I was studying classical archaeology, I spent a week or so crawling through the ruins of the public bath house of Ostia, Italy. Even in that Roman port town, something like the Brooklyn of the empire, bath design exceeded anything in the post classical world. Each room had its own distinct shape and purpose. After the apodyterium, you pass through the solarium, then the tepidarium, on to the caldarium, finish off in the frigidarium and do it all over again. The architecture and even the brick were designed for optimal bathing performance. The walls were hollow to allow the furnace fueled gasses to radiate from all sides in a system we now call hypocaust heating. Olive oil served in place of soap, with a tool called a strigil used for scraping off the dust of the Campania. No one in history was better bathed than a Roman.

The line of descent from the Baths of Caracalla to the Baths of 10th Street might represent the decline and fall of the bathing empire. From Rome to Byzantium to the East back West by way of the Pale of Settlement — to here, a dank, century-old New York City basement. Like the memory of Rome, the achievement of the Russian and Turkish Baths is that it has survived at all.

The Russian and Turkish Baths, photograph by Weegee

I’ve become known here as ‘professor’. The other regulars are mostly hipsters, oldsters and Jewish Orthodoxers. Before the shutdown, and hopefully again soon, I would go for a late lunch of borscht and Baltika beer. The unassuming canteen off the check-in desk served up highly respectable Russian fare surrounded by the fading autographs of television newscasters, Finnish diplomats and the stars of Superman II. As my order was prepared, I entered the changing room of mismatched lockers to the smell of cooked socks and put on the provided robe, which was more like a scratchy black sheet. The more you go, the more you know to opt out of the shorts and shoes they give you and bring your own swimsuit and shower slippers. I also started carrying my own Russian banya hat. It is a felted affair of elvish shape with Cyrillic lettering that I was once told reads ‘Queen of the Baths’. Oh, well. The sides curl up to transfer the water dumped on your head into a cooling trickle.

They say the Russian & Turkish Baths date back to 1892. The condition of the establishment leaves little doubt of its antiquity. The building is a tenement walkup with a basement long ago converted into a set of highly overheated rooms. In the 1980s, the bath’s two Russian owners, Boris Tuberman and David Shapiro — the latter died in May while planning the reopening — purchased the establishment and soon thereafter split their ownership to run it on alternating weeks. The unusual arrangement confused many and caused divided loyalties among the patronage, to which I remain a neutral party. But it also introduced the necessary inertia to ensure that few concessions were ever made to the changing times, including our own.

Everyone there knows what to do, or soon learns, with their own bathing ritual moving from one room to the other. I always start with the Aromatherapy Room, a steam room where someone covers the light with a wet towel and douses the spigot with essential oils. From there I head to the Turkish Room for the hot, wet heat. Inside are walls of overactive steam radiators surrounding three tiers of splintering bleachers. By the door is an ice shower, which contributes to the dankness and no doubt the spalling rust of the vaulted cement ceiling.

Last comes the Russian Room. It is the darkest and most Chernobyl-like. The temperature reaches over 200 degrees, fed by its own oven. When the oven door is left open, the radiant sensation has to exceed 3.6 Roentgen. Again there are tiers of benches, this time made of sizzling stone. I know not to take the top row on my own. Too hot. I like to leave easy access to the water trough, where you can cover yourself in buckets of ice water for some relief.

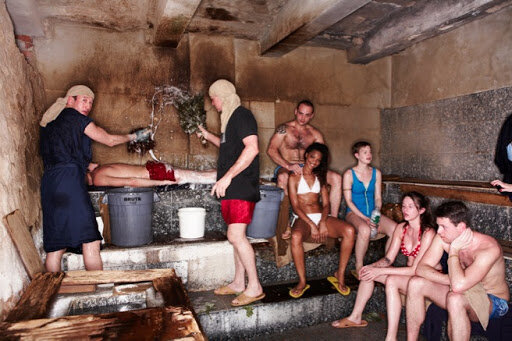

The “platza” as administered in the Russian Room of the Russian & Turkish Baths

On most visits I order up a service called the platza. Viktor, the bath’s most famous attendant, knows me well. His special treatment resembles the sensation of traveling through a car wash while being waterboarded. Administering the platza also greatly pleases Viktor, which is good because he must perform these duties in the burning heat. Into the Russian Room we go, cooling an upper corner bench by the oven with a towel soaked with a bucket of water for me to lie upon. Another towel then goes over my head, which Viktor splashes with water at semi-regular intervals when he is not cooling himself.

The platza proceeds for some 15 minutes. The ablutions involve the application of oakleaf branches that have been soaked in oily soap. During the procedure Viktor says little aside from ‘Yes’, ‘Good’, and ‘I kill you’ as he brushes and smacks the branches across the skin. The action removes the body’s toxins and just about everything else. The sensation also makes everything seem even hotter and, in fact, induces a temporary fever in the body, which I understand can have salutary benefits. Fortunately, Viktor also has a special sense for just when the body is about to become sous vide, and so he will splash you once in a while with a little cold water.

When it is all over, and Viktor congratulates your strength and requests your tip, I head to the cold plunge. This dark, refrigerated pool with a chemical smell is cooled to 40 degrees. It feels like it. The feet hurt the most. But the experience has also inured me to extreme changes in temperature. It is a good reminder that we are not created to be reptiles; we are warm blooded creatures. I have since taken my cold plunging to Coney Island, where I have sometimes joined the Polar Bear Club on their Sunday swims. The body’s reaction to cold water is flight, then fight. After a few minutes of dizzying unpleasantness, the flesh energizes with rushing blood and starts to feel warm. But the experience is best left to knowledgeable companions. If you are in there too long past the 10- to 15-minute mark and start to feel overly excited, it is time to get out.

At the Russian & Turkish Baths, the experience is complete with a brief rest on the roof deck. At one time this area was modeled on a Russian dacha, or country house. There are some fading murals to attest to this, but with benches made of broken plywood and torn foam, the area now resembles a squatters’ encampment. No matter: whatever the season, after the baths, the atmosphere here always feels ideal.

Like the Russian & Turkish Baths, the bath houses of Rome were cultural pavilions, even more so than in Greece, where this bathing culture originated. The Roman baths had restaurants, performance spaces, massage areas and gymnasiums. The Egyptians can keep their great pyramids. Rome’s real achievements, the gravity-fed aqueducts that moved 300 million gallons of water a day, created the world’s best baths. At one time there were 900 bathhouses in Rome alone. The Baths of Caracalla covered 27 acres and were the inspiration for New York’s original Pennsylvania Station. When one Roman emperor was asked why he bathed once a day, he replied it was because he did not have the time to bathe twice a day. When I return to the 10th Street Baths, I know I’ll feel the same way.