THE NEW CRITERION, April 2022

Going under with the overclass

On troubling trends among the elite. Part VIII of the series ‘Western Civilization at the crossroads’

We don’t often hear about the plight of the overclass, but our progressive elites have a problem. They have become too successful, and their success is starting to show poorly. Over the last decades, these elites have experienced the traumas of contemporary life very much in reverse to most Americans. Our difficulties have been their triumphs. Our restrictions have become their liberation. With ever greater efficiency, they have become the creditors to our debts, the marketers of our drugs, the title-holders of our homes, and the sellers of the fruits of our industry. They have risen as many others have fallen. They are good at what they do, and for this they have been handsomely rewarded. No one would deny a payment for a job well done. Yet these victories have demanded ever greater tribute from the vanquished. Progressive elites have taken their successes out on the rest of us.

America has always had its elites. For much of the country’s history, American elites have been the envy of the world. Elite ingenuity drove American prosperity. Elites also returned their wealth to the public trust through their patronage of culture and medicine and their promotion of civic uplift. Their astonishing acts of generosity—to museums, hospitals, schools, libraries, parks, opera houses, and many other outlets of culture and the arts—enriched American civic life in a manner unprecedented in human history. Even the most hard-hearted industrialists understood the calling, the urgency, of these expressions of civic virtue. “All have derived benefits from their ancestors,” wrote Horace Mann, the nineteenth-century American educational reformer; “and all are bound, as by an oath, to transmit those benefits, even in an improved condition, to posterity.” Through the aspirations of art and architecture, through the study of great literature, and through the care for common suffering, the institutions they created—those “little platoons,” in Edmund Burke’s appreciation of small associations—promoted nothing less than the culture of democracy.

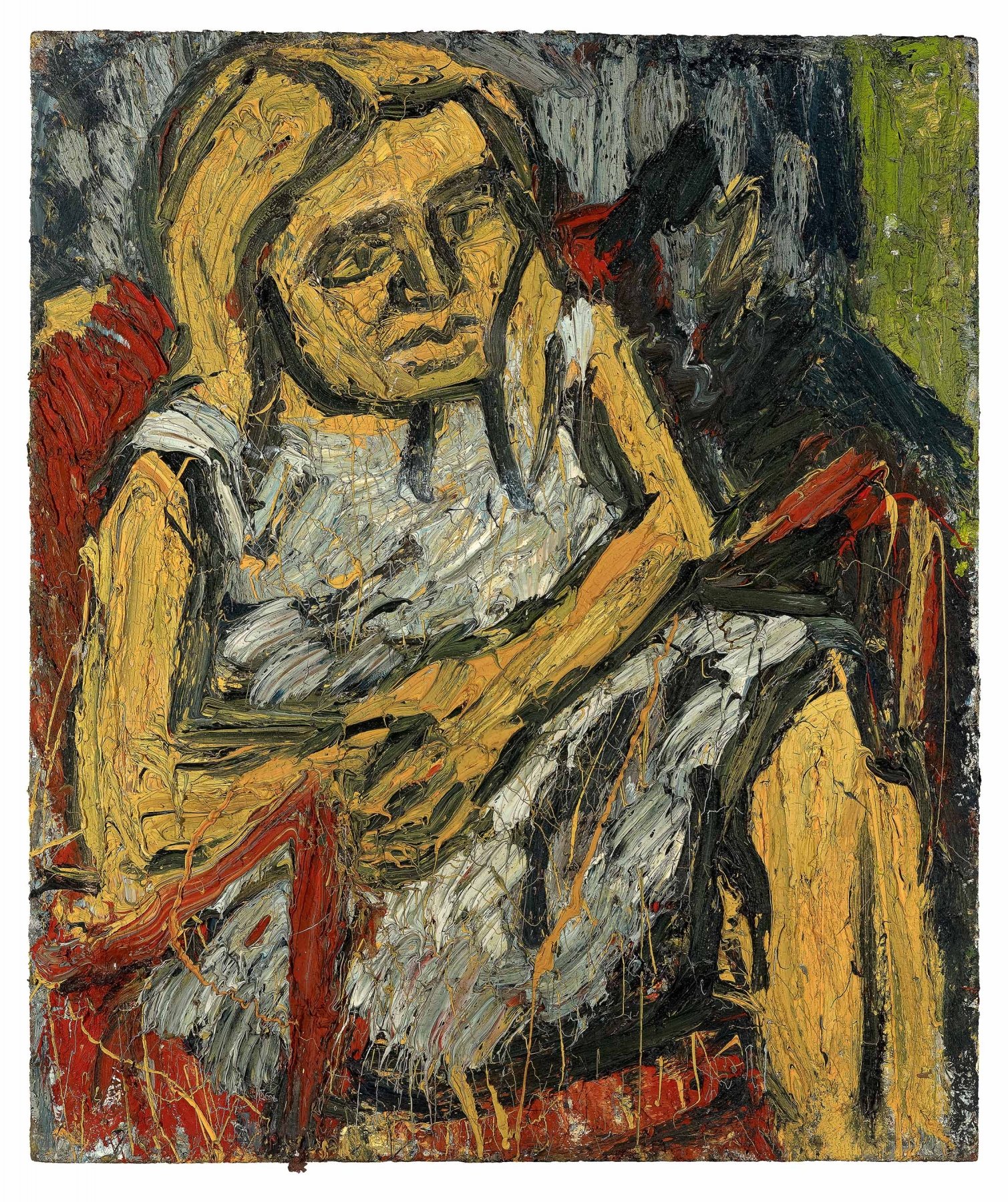

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress I: The Heir, 1734, Oil on canvas, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Americans are still the great beneficiaries of the historical largesse of this untitled nobility. The institutions that continue to enrich the country’s lives are, by and large, the continuation of the ones founded a century ago or more by elite benefactors. As an expression of the importance that the American Founders placed on these private associations—for example, when it comes to the country’s oldest schools—this institutional history extends to before America’s national beginnings. The cultural enrichment that American elites helped to nurture has been an impressive reflection of the country’s democratic ideals.

And yet, rather than support these institutions as pinnacles of civilizational achievement, many of today’s elites seem determined to undercut them. They gnash their teeth at their own history. They rend their garments at their own complicity. Then they make an active show of ripping apart their charges at the seams: closing the books, covering the art, destroying the monuments, censoring the students, canceling the discourse, and ridiculing the historical mission. Such impulses inform elite behavior across the Western world. This show of cultural weakness has been a provocation with deadly consequences. For those of us still concerned with the preservation of wisdom—an inheritance of culture that transcends politics—the results have been heartbreaking. For those concerned for the fabric of democratic nations, the effects are now all the more horrifying.

A culture war by proxy

Americans find it distasteful even to speak of their elites. In a supposedly egalitarian society, the idea strikes most observers as improbable. The mere mention of an elite class can sound sinister and un-American. Compared to the Left, conservatives are even less inclined to criticize elite manners and mores, even if Tom Wolfe could be their unparalleled anatomizer. But the truth is that, far from the magnanimous elites of old, today’s overclass increasingly seeks to direct what we see, what we read, what we say, and what we hear. They consolidate and monopolize. They inflate and devalue to their maximum advantage. They also tip the scales, cook the stats, stack the deck, and rig the games while championing the fairness of the outcomes. In today’s meritocracy, these elites are always meant to be the best. In today’s democracy, the winning candidate is always supposed to be their own. They flood people’s neighborhoods, screens, and lives with destabilizing interventions. They feign concern before throwing back middle-class worries as pathologies in need of their control. The uncertainties of the many contrast with the verities of these few. And they are merciless about it. They have it figured out. They mock those who do not. Rather than lift up their fellow citizens through their charity and good will, this overclass seems determined to invalidate that common pledge, from the Declaration of Independence, “to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.”

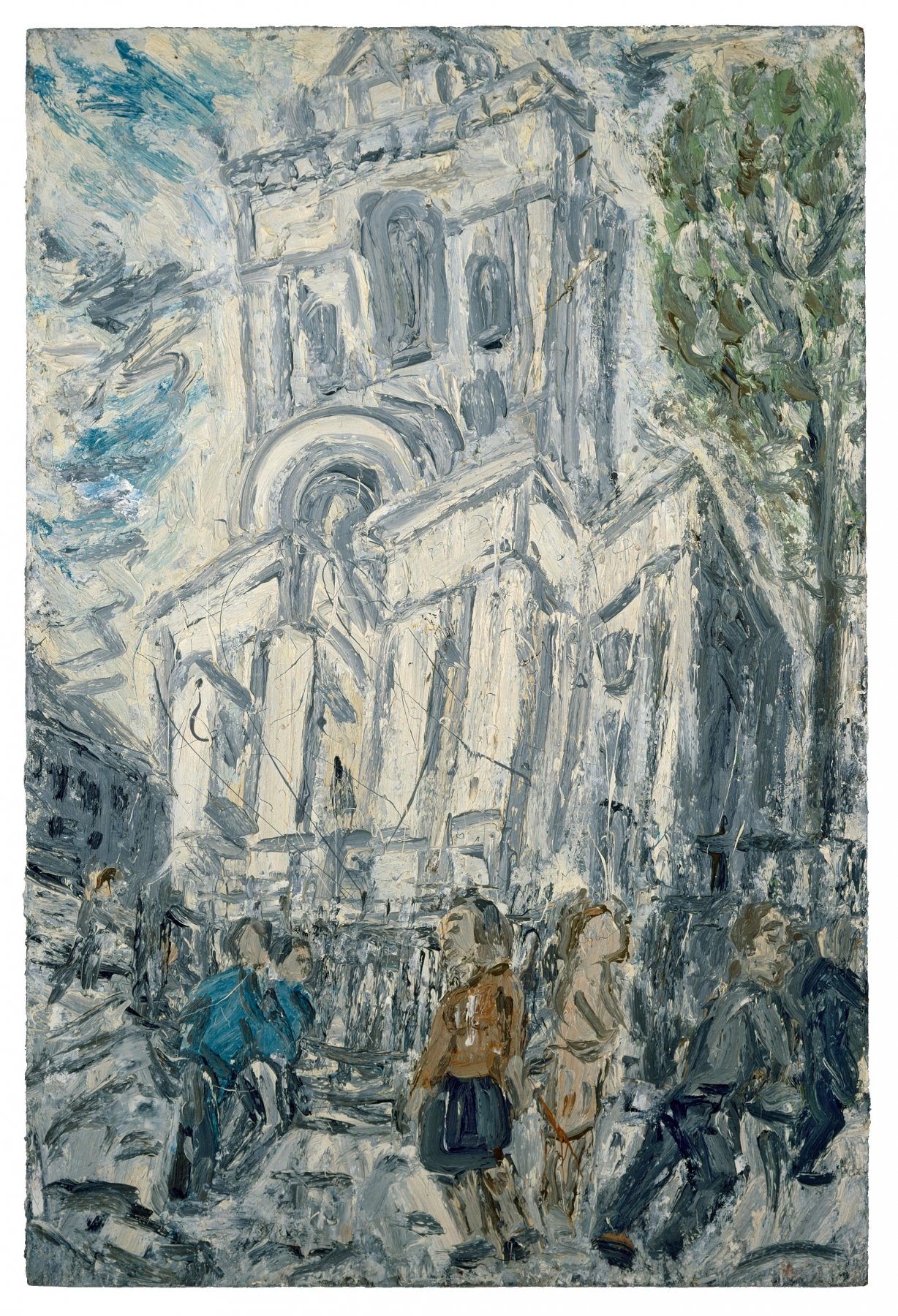

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress II: The Levée, 1734, Oil on canvas, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Elite attacks are made under the banner of a mutable list of causes: social justice, climate justice, indigenous justice, trans rights, black lives, anti-racism, and so on. Tomorrow it will be a new combination and permutation of progressive politics. The shifting battlelines are a strategy of the offensive. While many of the attacks seem to originate from below, it is easy to miss the fact that the bombs have been placed, timed, and set to detonate by those at the top. It is a culture war largely waged by proxy. Today’s activist elites seek to undermine the cultural legacies of the institutions they control precisely because these institutions have promoted—through their books, their art, their buildings, and their concerns for our well-being—democratic aspirations and cohesion. It is a spirit they now despise and wish to undermine.

Consider the case of Nikole Hannah-Jones. The much-discussed author of The 1619 Project would be little more than a social-media scold were it not for her platform at The New York Times, the company behind her publication and promotion. Despite the widely accepted debunking of her project, the “newspaper of record” has only doubled down on its initiative to undermine the legitimacy of the United States by slandering it as a slave-owning conspiracy, rather than a country that has shed more blood than any other to uphold democratic ideals. As noted in these pages, during the riots of 2020, which caused dozens of deaths, $2 billion in property damage, and untold suffering in its aftermath, Hannah-Jones wrote that it would be “an honor” for this looting to be called “the 1619 riots.” She continued: “The history of non-violent protest has not been successful.”

There was a time when reproducing the diagram of a Molotov cocktail—as The New York Review of Books did in 1967—would be considered an act of fringe journalism. Now The New York Times can read like a guide for anarchists and an apology to the criminal class. In 2017 the Times published an article called “How to Pull Down a Statue,” which it offered under the heading of a “Tip.” In 2021 it reproduced instructions by Decolonize This Place further detailing “how to take down a monument.” Here it offered such advice as “For every 10 ft of monument, you’ll need 40+ people” and “everyone needs to be wearing gloves for safety.” It concluded: “Just keep pulling till there’s good rocking, there will be more and more and more tilting, you have to wait more for the obelisk to rock back and time it to pull when it’s coming to you. Don’t worry you’re close!” The Sulzberger family, which has controlled the Times since 1896, has found great profit in such stridency. As it trumpeted in its own report last fall, the newspaper’s circulation has only increased, advertising revenue is up, and its “balance sheet surpassed $1 billion in cash as it continued to build its free cash flow.”

These are not isolated examples of elite behavior. Even compared to mainstream liberalism, noted Michael Tomasky, the editor of The New Republic, “It’s an undeniable fact that Democratic Party elites, progressive activists, foundation and think-tank officials, and most opinion journalists are well to the left.” Elite foundations have given over $12 billion to institutions pushing the progressive ideology of “racial equity”—as opposed to racial equality—in the last year alone. These include the Ford Foundation ($3 billion), Mackenzie Scott (Bezos) ($2.9 billion), JPMorgan Chase ($2.1 billion), the W. K. Kellogg Foundation ($1.2 billion), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation ($1.1 billion), the Silicon Valley Community Foundation ($1 billion), the Walton Family Foundation ($689 million), The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation ($438 million), and the Foundation to Promote Open Society ($350.5 million). One of the largest donors to “Yes 4 Minneapolis,” the charter amendment to dismantle the city’s police department, was from George Soros’s Open Society Policy Center. The source for this information is not some dog-whistling outfit from beyond the pale but, again, The New York Times.

It should be said that many elites, perhaps a greater percentage of them, mainly see opportunity in the incendiary rhetoric. They mete out medicine based on race, for example as was done with scarce covid treatments, while employing their own concierge doctors. They care for little beyond themselves. They are more than happy to outsource the burden of concern to the teams of progressive agonizers now on their payroll. They are also content to watch the burning. They observe the fires from a safe remove as the conflagrations never touch them. The fire-breaks, in fact, only serve to enhance their sought-out isolation. The burned-over populace only contrasts with their own glittering ascendancy. But ultimately, whether they are active or passive participants, every challenge this overclass puts out is a challenge to national legitimacy.

Elites have not given up on status. Their behavior is centered around maintaining cultural control and passing these privileges on to their heirs. At the same time, from art to architecture, statues to books, they want to break the chains of civic inheritance because these works are in a public trust that they no longer trust. In the name of national reckonings, they seek their own disunion. Inspired by this anti-democratic impulse, this revolt against the masses, today’s elites promote progressive fronts to undermine national sovereignty and embitter common citizens while consolidating their own power and position.

The betrayal of democracy

Arecurring theme of this series is that progressive elites now drive a Western civilization at the crossroads. But just how did our highest classes become an overclass of toxic privilege? Over a quarter century ago, the social observer Christopher Lasch wrote about dangers that he diagnosed under the title Revolt of the Elites. Produced in his dying days, Lasch’s warning came out as a feature in Harper’s magazine in November 1994 and then as a book by Norton in 1995, this time subtitled “The Betrayal of Democracy.” This challenge to democracy is the key to understanding elite dynamics. Lasch cautioned that the “chief threat” to Western culture no longer comes from an aggrieved underclass but from “those at the top of the social hierarchy”:

who control the international flow of money and information, preside over philanthropic foundations and institutions of higher learning, manage the instruments of cultural production, and thus set the terms of public debate—that have lost faith in the values, or what remains of them, of the West. For many people the very term “Western civilization” now calls to mind an organized system of domination designed to enforce conformity to bourgeois values and to keep the victims of patriarchal oppression—women, children, homosexuals, people of color—in a permanent state of subjection.

Lasch intended his title to be a riff on The Revolt of the Masses, the book by José Ortega y Gasset first translated into English in 1932. Ortega saw the civilizational threat of his era coming from the “mass man.” Observing the births of both Bolshevism and fascism, Ortega feared an ignoble force rising up from below that maintained no obligations to history. This mass man insisted on “complete freedom.” He was the “spoiled child of human history.” All the while he maintained a “deadly hatred of all that is not [him]self.”

Now in a “remarkable turn of events” that “confounds our expectations about the course of history,” wrote Lasch, something that Ortega never dreamed of has occurred. Lasch was a writer coming from the Left. He could be too quick to denounce open markets. Some of his presentations could be vague and generalizing. But as an observer who became highly critical of the progressive culture promulgated by the new elites and their institutions, Lasch was right to home in on the class conflict that drives much of our more superficial political dynamics. Reviewing the book in these pages in April 1995, Roger Kimball called Lasch “one of our most articulate and earnestly plangent social critics.”

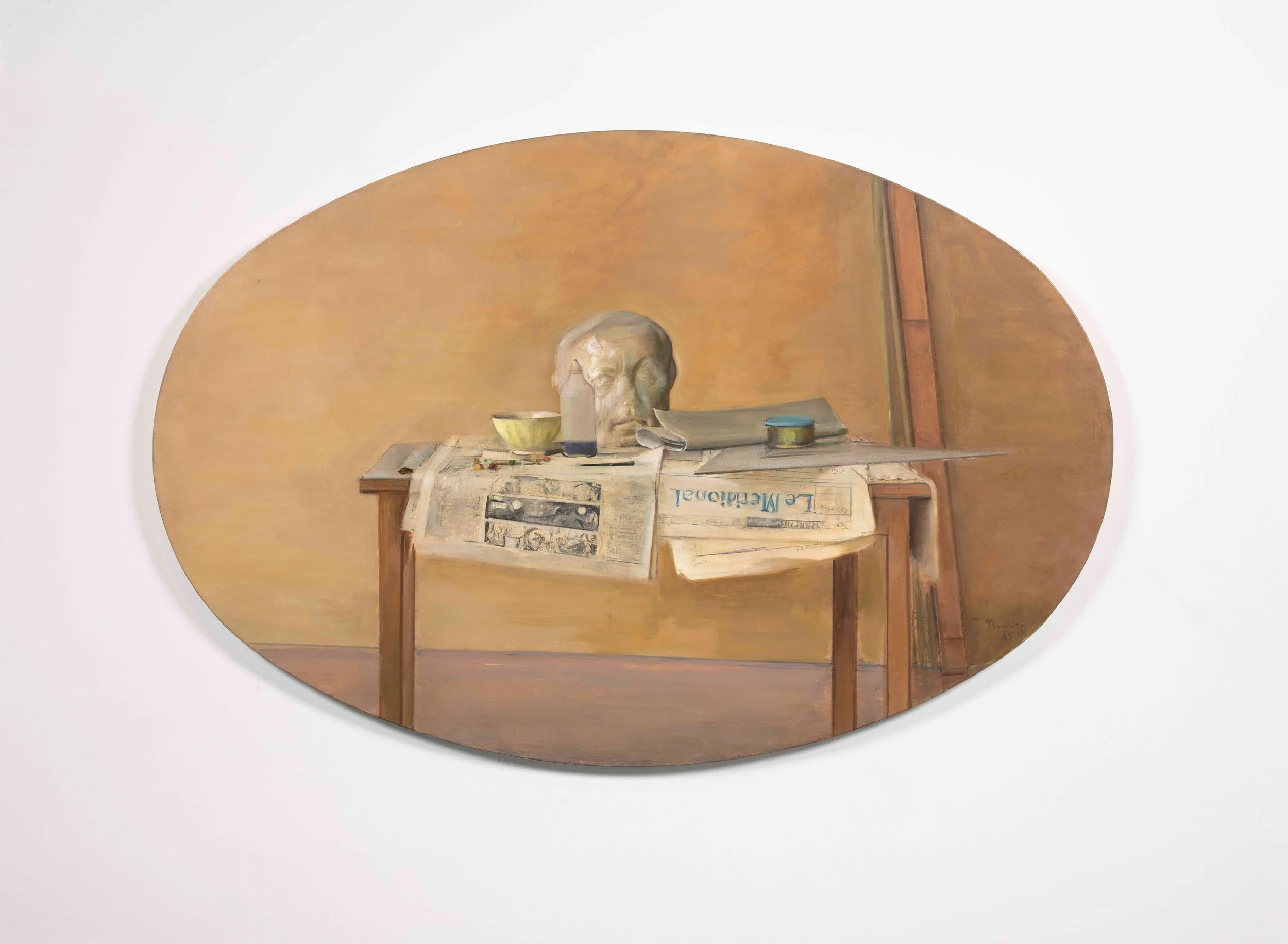

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress III: The Tavern Scene, 1734, Oil on canvas, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

“The cultural wars that have convulsed America since the sixties are best understood as a form of class warfare,” Lasch observed, “in which an enlightened elite (as it thinks of itself) seeks not so much to impose its values on the majority (a majority perceived as incorrigibly racist, sexist, provincial, and xenophobic), much less to persuade the majority by means of rational public debate.” Ever more detached from public life and civic engagement with a full spectrum of fellow citizens, elites seek to “create parallel or ‘alternative’ institutions in which it will no longer be necessary to confront the unenlightened at all.” The West as it exists is irredeemable, deceitful, dangerous, and in need of their elite control. The result is a class warfare waged from the top, directed down.

Lasch saw a long history of geographical sifting, “assortative mating,” and other social factors as contributing to this widening social isolation and contempt. Management and labor no longer live in the same towns. Rooted industries have given way to rootless capital markets and abstract information technologies—which, we might say, now more resemble misinformation technologies. For much of America, “the decline of manufacturing and the consequent loss of jobs; the shrinkage of the middle class; the growing number of the poor; the rising crime rate; the flourishing traffic in drugs; the decay of the cities—the bad news goes on and on.” Meanwhile such concepts as “meritocracy” and “upward mobility,” even if pursued fairly, merely leave our “elites more secure than ever in their privileges (which can now be seen as the appropriate reward of diligence and brainpower) while nullifying working-class opposition.” Through the myth of social mobility, elites in fact “solidify their influence by supporting the illusion that it rests solely on merit.” The result is a “two-class society in which the favored few monopolize the advantages of money, education, and power”—results that are not only supposed to be “fair,” but are now also unquestionable. “When confronted with resistance,” Lasch observed, elites “betray the venomous hatred that lies not far beneath the smiling face of upper-middle-class benevolence.”

“There has always been a privileged class,” said Lasch, “even in America, but it has never been so dangerously isolated from its surroundings.” Contempt now replaces elite obligation and noblesse oblige. “Simultaneously arrogant and insecure,” Lasch wrote, “the new elites regard the masses with mingled scorn and apprehension.” They now despise their countrymen, especially those who do not pay tribute to their superiority. Meanwhile, “ ‘Middle America’—a term that has both geographical and social implications—has come to symbolize everything that stands in the way of progress: ‘family values,’ mindless patriotism, religious fundamentalism, racism, homophobia, retrograde views of women.”

We are the virus

This elite distaste for the lower classes merges sterility with revolutionism. Where the isolation of the classes is not an option, their prescription is sanitary control: Upper-middle-class liberals have “mounted a crusade to sanitize American society—to create a ‘smoke-free environment,’ to censor everything from pornography to ‘hate speech,’ and at the same time, incongruously, to extend the range of personal choice in matters where most people feel the need for solid moral guidelines.”

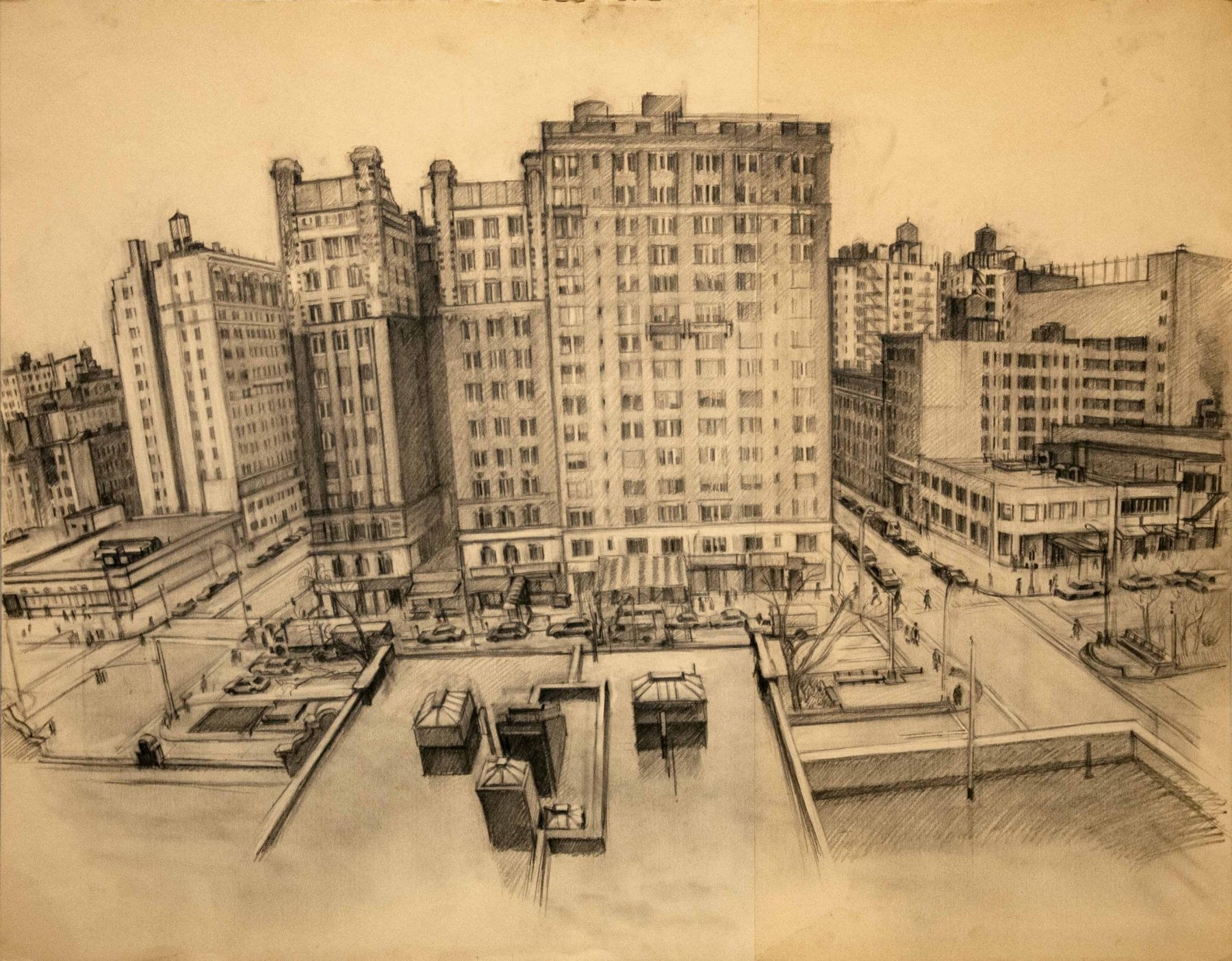

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress IV: The Arrest, 1734, Oil on canvas, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

How remarkable is it to consider that, writing over a quarter century before our pandemic closures, distancing mandates, and vaccine “passports,” Lasch diagnosed the sanitizing urge of our elite culture. For all of the talk of institutional “access,” more than half of black Americans, for example, were not permitted into New York restaurants, gyms, movie theaters, or museums for over a year due to vaccine mandates they did not meet. The numbers were even lower for some venues, where proof of a third shot, along with picture ID, has been required for entry. The result is that the rich are buying up all the seats, figuratively and literally, around them. Progressive elites seek to escape even the air we breathe. With great fanfare, they launch themselves into the vacuum of space and sink themselves into the isolation of the seas. And while they await their earthly escape, at the very least, they expect a double masking from their chefs, trainers, and housekeepers while they enjoy the clean air of Aspen, Napa, and St. Barts.

Ever more removed from the general population, elite life during this pandemic has never been more rewarding. They have enjoyed their family camp in the Adirondacks, the river that runs through their ranch in Montana, the shifting tides rising and falling by their house in the Caribbean. Their only illness, as the saying goes, has been their ongoing bout of “affluenza.” Twenty-five years ago, at the time of Lasch’s writing, America’s richest 20 percent controlled half of the country’s wealth. As of 2021, the top 10 percent control 70 percent of the country’s wealth. The top 1 percent alone controls nearly a third of the country’s wealth. The top 50 percent hold 98 percent of the wealth. That leaves the bottom 50 percent with but 2 percent, a division that has only grown more stark through the pandemic as inflation, crime, and learning loss now add to the disruption. This all means that, as American cities were looted and burned, and the working classes have had nothing else to do but to mask up and clock in, a pajamaed overclass has stepped happily aside from the final requirements of democratic life. All the while, as Lasch observed, the elites “find it hard to understand why their hygienic conception of life fails to command universal enthusiasm.”

The elite attack on democracy often comes out of this same fetish for sanitation. For progressive elites, structural racism, much like a viral pandemic, is a silent killer. The less you see it, the more likely you are to be already infected. Resist its treatments, and the more you are complicit in spreading its disease. You could be an asymptomatic carrier and still kill others. You could have racism and not even know it. For elite policy-makers, no treatment is too harsh, no restriction too extreme, no position too out-of-step with common sense to get to racism zero. The coronavirus response has proven itself to be merely a dry run for even greater encroachments of government surveillance and control. China continues to woo the world’s elite with its permanent class of insiders, who are happy to regale their Western hosts with the siren song of benevolent, technocratic rule. Now from Europe to America, the tracking technology is in place to be deployed from one virus to the next.

Just as elites do not respect the popular vote, they do not respect the popular voice. Progressive contempt for the common man, of course, goes back more than a century. There has always been a subset of elites who, despite a purported interest in the downtrodden, are obsessed with overpopulation, sterilization, and generally advocating for “less of you and more of me.” An enlightened interest in conservation, for example, has given way to the unhealthy worship of the environment and its eschatologies. The earth, the body, and the mind must now be detoxified by the same elite treatments.

“Compassionate attention, we are told, will somehow raise their opinion of themselves,” Lasch wrote of the supposed beneficial effects to the underclass of a war on speech; “banning racial epithets and other forms of hateful speech will do wonders for their morale. In our preoccupation with words, we have lost sight of the tough realities that cannot be softened simply by flattering people’s self-image. What does it profit the residents of the South Bronx to enforce speech codes at elite universities?” Since Lasch penned these words, elites have only doubled down on a censorious worldview that has indeed shown little profit to “the residents of the South Bronx.” The gambit, however, has greatly profited elite institutions and their well-heeled class of insiders.

Diversity is their strength

Many have called social justice a new world religion. The enforcement of so-called justice over and against precedent and reason, almost exclusively a “rubbing out” of nuance rather than a “filling in,” certainly conveys a religious zeal. The negative dialectics of this form of justice cannot be overstated. For all the talk of “expanding the narrative,” the results always seem to be an editing down of the complexities of the human condition to the same short story of oppression. In the interest of “safety,” this fetish for sanitation, this program of social justice, grants the opposite of just access. Instead it places limits on the art we can see, books we can read, ideas we can think, words we can say, votes we can cast, food we can eat, energy we can use, and people we can befriend.

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress V: The Marriage, 1734, Oil on canvas, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

A term such as “ ‘diversity’—a slogan that looks attractive on the face of it,” Lasch observed, “turns out to legitimize a new dogmatism, in which rival minorities take shelter behind a set of beliefs impervious to rational discussion.” Taking advantage of America’s unparalleled empathy for racial redress, this strategy of divide and conquer is nothing new. Swaths of humanity are balkanized into ever smaller splinter groups of identity factions. They are destabilized through chaotic impositions on whatever remains of faith and family. And they then have no choice but to turn to their elites to keep the peace. In this scenario the overclass is both fire marshal and chief arsonist, lighting the flames and ringing the bells.

There are plenty of true believers in this progressive faith, especially along the American coasts and in urban centers. Their politics gives meaning to their successes and justifies the failures of others. At times in America such dogmas seem to have activated a sleeper cell of Mainline Protestants—from what we might have assumed was their eternal slumber. Those held by these believers to be latter-day martyrs would have died in vain if the deaths had not resulted in conflagration. Whether the subsequent promotion of looting and “defunding” has done more than anything else to endanger the lives of poor Americans is beside the point. Elites have acquiesced to a chaos and violence that disproportionately affects the underclass—precisely the people they say they want to help. For such believers, violent purification is a justification and an end in itself. A race war, or an environmental disaster, or some other end-of-times revelation would give meaning to their dying religionism.

Few outside of elite circles, of course, hope for any of this; we would be rid of these turbulent priests and other outspoken enablers were it not for their supporters in global foundations, media, entertainment, tech, government, and finance. For them the reality is often transactional: our overclass has sold out to the highest bidder and papered it over with a diversity initiative. For the elite order, the system works. Having churned up the waters, they skim over the waves. Nowhere is this more apparent than in American education. The more uniform the school, the more it will assure you of its commitment to diversity. The more exclusive its admissions, the more we are told of its inclusivity. The more it hoards its endowment funds, the more it appeals to equity and justice. To be sure, we might still find vestiges of the “old elite” legacy clinging to these institutions. The residue of great books, great educators, and great ideas is hard to completely scrub away. Some teachers inherently reject the censorious mandates of Critical Race Theory and the imposition of administrators in the classroom. Yet the artificial scarcity, the goosing of admission yields, the identity dogma, and the false appeals to “merit” all serve to mask the true aims of institutions that exist primarily to preserve elite privileges.

Any non-elite entrants, hand-selected by these insiders, are there to play a part in the equitable fantasy through a role not of their choosing. They are paraded in front of the banquet and are shown eating at the table. They just must obey all the directions of this legitimacy pageant until they exit stage left. For the “holiday dinner” at Yale University, for example, the freshmen are invited to a feast “decorated with holiday lights, ice sculptures, and gingerbread houses,” according to the school’s admissions page. “Now add eggnog, hot apple cider, prime rib, sole, roasted turkey and ham, golden potatoes, sushi, shrimp (in the shape of a Y), lobster, cupcakes, apple pie, cheesecake, fruit, chocolate covered strawberries, and a twelve-foot challah.”

In December 2021, despite its own self-imposed lockdown, the school went ahead with a two-night revel. Unmasked students crowded around to record the decadence on their smart phones as, in stark contrast, a line of masked dining-hall workers could be seen pushing this “Parade of Comestibles” heaped with lobsters, lamb chops, and an ice-sculpture sleigh piled with shrimp. “The food had to go somewhere,” noted Caleb Dunson, a black undergraduate and opinion columnist for the Yale Daily News, in a piece called “Abolish Yale,”“so people started taking it by the pound. Students lined up near the meal station back of Commons, waiting to grab entire crabs and lobsters to take home with them. They grabbed turkey legs the size of my forearm and munched away at them too. We all feasted like royalty. Just two blocks away, on the city’s Green, homeless people froze and starved in the bitter New Haven night.”

I left that dinner feeling disturbed and disheartened. On the walk back to my Old Campus dorm, I realized that I felt this way quite often while at this University. There’s something unsettling about Yale, about the way it operates, about its very existence. . . . [The school’s] idea of individual-driven change reeks of false meritocracy and trickle-down theory, and gives the University the cover it needs to hoard wealth and resources.

Unsentimental education

For those on the inside, the recent college-admissions scandal known as “Varsity Blues” was shocking not for its criminality but for its lack of scale and ambition. A fixer paying out bribes to the sports coaches of second-rate schools to cover non-athletic applicants is but a two-bit grift. Compare this to the subterranean pipelines that have now been laid by our elites to connect their families to the best schools, the greatest resources, and the highest potential future outcomes. There have always been elite connections. The irony is that, in this more “equitable” world, our overclass can now be just about assured of it. A high-speed rail tunnel might as well run between their child’s room and the college building with their name on it. For those more problematic cases, a delta force of tutors, psychologists, strategists, and trainers is there to operate as a shadow student, providing an illusion of excellence that can seem far better than the real thing. Professionals are at the ready to do the homework, write the papers, extend the test times, shape the identity narrative, and apply to the schools. “Here is my laptop. The paper is on Macbeth,” is how one elite tutor described a typical interaction. Some of his students, he said, had never done a minute of homework in their lives. Give an A- for such work and you will hear about it. Anything less than an A is unacceptable for such expenditures. Elite parents have all the email addresses in their assistants’ files. They are not above demanding a meeting the next morning to make the grade.

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress VI: The Gaming House, 1734, Oil on canvas, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

There are, of course, still some old elites who hold on to the democratic faith of their ancestors as if they were Russian Old Believers. Some of the Olympian thunder we have heard from beyond the clouds concerns this fight between old and new in our board rooms, faculty lounges, and non-profit institutions. In early 2021, for example, a math teacher named Paul Rossi at New York’s Grace Church, a private preparatory school, questioned a segregated racial-sensitivity training session organized by his institution. Corralled into a group of “white-identifying” students and faculty, Rossi was presented with a slide of the supposed characteristics of white supremacy. Such a list of “white” traits might come as a great insult and surprise to anyone, of any color, not versed in elite semantics, but the catechism has been making the rounds at many elite institutions. The Smithsonian’s own National Museum of African American History & Culture recently presented the nuclear family, rational linear thinking, decision-making, respect for authority, delayed gratification, punctuality, and being polite all as further “signs of whiteness.”

At Grace Church, the consultant asked if anyone was having “white feelings” as they looked over the list. “What makes a feeling ‘white?’ ” Rossi asked. The school then reprimanded the teacher for “creating a neurological imbalance” among his students by questioning their racial training: “When someone breaches our professional norms,” read the complaint against him, “the response includes a warning in their permanent file that a further incident of unprofessional conduct could result in dismissal.” After Rossi confronted his head of school for this racialized drilling of students and faculty, the headmaster offered him a contract renewal only on the condition that he engage in “restorative practices” for the harm he had done to black students.

It is no coincidence that the traits now identified as “white supremacist” are the same ones that serve as the foundational values of democracy. Many elite schools, where day tuition approaches $60,000 a year and parents are recruited to give millions more, have become the training grounds for a post-democratic future. They will silence any diversity of viewpoint over concerns for student “safety” caused by “violent” words and ideas. The freedoms of speech, of assembly, and of conscience, as well as equality under the law, are all belittled as the values of an outdated racist order in need of elite replacement. Progressive “pain points” are then activated over the questioning of identity dogma to shuttle dissenting opinions to the door. Progressive elites are more than pleased when presented with the opportunity to winnow their ranks, sharpen their conditioning, and make examples of their apostates.

A decadent isolation

Sensing the progressive interests of today’s elite universities, for which they ultimately “prep” their students, many elite preparatory schools have only redoubled their identity agenda. This is true even after a few high-profile defections: Megyn Kelly, the television anchor, pulled her children out of New York’s Collegiate and Spence Schools; Gabriela Baron, a daughter of Cuban immigrants “increasingly concerned about . . . a de-emphasis of academic rigor and a single-minded focus on race, diversity and inclusion,” did the same at Spence, where she was an alumna and trustee; Bion Bartning, of Jewish, Mexican, and Yaqui-tribe background, removed his children from the Riverdale School and has since created a foundation called fair, dedicated to confronting the “intolerance and racism” at the heart of identity politics.

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress VII: The Prison, 1734, Oil on canvas, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Collegiate’s response has been to convene a seventeen-member task force to address its “history and symbols.” Released after three years of study, the group’s 407-page report called for recasting “Peg Leg Pete,” the school’s Knickerbocker mascot, over its “Eurocentric and racist overtones to its crude depiction of a disability, a peg leg,” according to The New York Times. More telling, “to make clear that we are a fully inclusive and welcoming community,” the report recommended the elimination of the reference to God on the school’s seal: Nisi Dominus Frustra, “Without the Lord, [it is] in Vain,” from Psalm 127. The report concluded:

In the early years of the school, one of the major areas of focus was proselytizing Native Americans and others to Christianity. There is also a history of Christian hegemony in the United States that has been experienced as both exclusive and oppressive.

Other elite schools have similarly closed progressive ranks. At New York’s Dalton School, some parents questioned that institution’s anti-racist pledge to abolish any advanced course where black students did not perform as well as their white counterparts. At the annual meeting of diversity heads at the school, the keynote speaker then denounced this parent action for its “plantation mentality” and likened these “white supremacists” to the capitol rioters of January 6. Meanwhile at Spence, the school decided to tear out Les Vues d’Amérique du Nord, its ninety-year-old wallpaper designed by Zuber et Cie and only recently restored. The reason? Its “romanticized view,” which included both black and white Americans enjoying the countryside together, was “historically inaccurate.” In other words, the same wallpaper that was installed in the Kennedy White House in 1961, and which featured prominently in the background of the Obama administration, was removed because it was not racist enough. Meanwhile, the construction of Spence’s new multimillion-dollar athletic facility, featuring nine squash courts and an ecology center, went ahead as planned, destroying what remained of St. Joseph’s Orphan Asylum.

The well-trained elite

Even as much of America has now rejected the doctrine of Critical Race Theory, due to its exposure by Christopher Rufo and others, elite schools have instituted mandatory “anti-racism” training not just for students and teachers but also for parents, writing these obligations into enrollment and employment contracts. Would Glenn Loury and John McWhorter, outspoken black critics of anti-racism, now even be permitted to send children to such elite schools, let alone be invited to speak? McWhorter, author of Woke Racism, has called anti-racism “an illiberal neo-racism” that has “betrayed black America.” How about Ayaan Hirsi Ali? The Somali-born activist has written that “Anti-racism is the disease that it purports to cure. Its narratives of resentment are dividing us once again by race, weakening our hard-earned freedom and mutual trust, and threatening our children’s future. We have no option but to fight it as we once fought white supremacy.” Would such words violate an enrollment contract that is pledged to anti-racism? The answer is that, for all of their independence, the nation’s private schools still answer not only to their elite boards but also to accrediting consortia that function as centralized bureaucracies for the diversity industry—groups that have shown little interest in the values of free discourse, equal treatment, rigorous inquiry, or open dissent.

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress VIII: The Madhouse, 1734, Oil on canvas, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

And besides, why should most of today’s elites even want to complain? Diversity functions as a prime mechanism of class distraction. To elite sensitivities, “Black Lives Matter” sounds better than “Occupy Wall Street”—even as both movements have emerged from the illiberal Left. Racial activists and corporate America have developed a robust working relationship that promotes each of their interests. The elites get a hustle; the activists make a profit. Writing in Liberties Journal, the literary scholar William Deresiewicz, who has been critical of the “excellent sheep” raised in the folds of elite education, locates the assimilation of minority elites into this progressive culture:

It is elites within the Hispanic community who say “Latinx”; the vast majority of Latinos hate the word, when they have even heard of it. It is elites within the black community who propagate the dogma of critical race theory; blacks on average are actually more moderate than the typical white Democrat. It is elites within the Asian-American community who inveigh against assimilation; most Asian-Americans are busily assimilating. But then so are the elites, of all groups—so especially are the elites—and it is only their bad conscience, or, more charitably, their understandable ambivalence, that leads them to imagine otherwise.

Elites of many stripes have learned to benefit from the culture of identity politics. The prerogatives of black activism are now claimed by their white “allies.” A spectrum of grievances can shift from race to gender to other protected classes until it encompasses the elites’ own. The end result is that, from the British royal family on down, we are now presented with an aristocracy of grievance. The higher up we go, the greater the affront. After witnessing the shock of trans activists pushing their way into women’s sports, for example, we might soon see a generation of nonbinary athletes angling for their own division in college sports—and a legion of elite coaches, trainers, and professionals to make sure they get there. Unlike the shady dealings of “Varsity Blues,” however, an elite student shuttled through the pipeline to the nonbinary wing of the Princeton fencing program would be heralded in news stories—“a first!”—while dissenters would be branded as transphobes or TERFs, for “trans-exclusionary radical feminists.”

Diversity can indeed be “trained.” For the well-mannered elite, it is an easy game to play. Regulations always benefit insiders. The “diversity lens” offers up polarizing glasses that leave the world simplified into black and white and easier for their charges to master. The new, anything-goes rules of human gender are easier to learn than the old nuances of French gender. It is easier to fixate on human races than Latin cases—despite the talk of “Latinx.” It is also easier to discount the plight of America’s underclass when you cannot see it. Those who disagree are denounced as racist and “deplorable.”

Such provincials, of course, make up the vast majority of Americans, both black and white. They reject elite dogma. So their class complaints are redirected into race complaints. Or for their faith in America, they are written off for false consciousness. Or their protests over workplace restrictions are “unanimously condemned” for somehow promoting “anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, anti-Black racism, homophobia, and transphobia,” as the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said of his country’s trucker revolt. “Together, let’s keep working to make Canada more inclusive,” he concluded. How much better—so our elites would maintain—for power to be handed over to them. Only they have been trained in the language of identity. Only they have been conditioned in the syntax of grievance. Only they have worked their whole lives so as not to misgender others. The elites, simply put, will take it from here.

Awaking from the fever dream

As the world again commands our attention, we risk the loss of our own democratic future. This is especially true for a hard-working, non-elite generation that still believes in the blessings of liberty and the universal power of liberal education. Deserving first-generation Asian applicants continue to be kept out of Ivy League schools through an elite system of racial quotas. Meanwhile Dan-el Padilla Peralta—the elite-trained classics professor (Collegiate, Princeton, Oxford, Stanford) who obsesses over the “production of whiteness” residing “in the very marrows of classics”—is fast-tracked for Ivy League tenure.

Yet there is hope, especially from outside progressive circles. Thomas Chatterton Williams, the author of Self-Portrait in Black and White: Unlearning Race, writes about the transformation experienced by his black father in segregated Texas upon discovering Plato’s dialogues. Roosevelt Montás, an immigrant from the Dominican Republic and the author of Rescuing Socrates: How the Great Books Changed My Life and Why They Matter for a New Generation, had a similar encounter with the classics and now passes on that knowledge: “My students from low-income households do not take this sort of thinking to be the exclusive privilege of a social elite. In fact they find in it a vision of dignity and excellence that is not constrained by material limitations.”

Over half a century ago, believing that the salvation of our culture could be effected by its elite class, William F. Buckley Jr. proposed writing a book called The Revolt Against the Masses as his own answer to José Ortega y Gasset. Witnessing the elite self-abnegation of the 1960s, he was never able to finish it. Concerned citizens must now shake elite culture from its fever dream. Free-speech leftists, cultural conservatives, Great Books liberals, traditional feminists—all must realize the role they play in this awakening. The time is right for a revolt for the masses. But for any true reckoning, today’s elites must also look to themselves and their own decadent isolation. At the crossroads of Western civilization, the signs point to our democratic salvation or our common ruin.