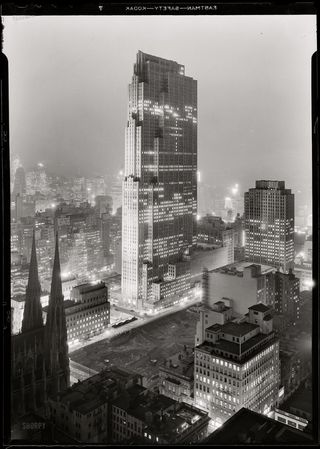

Rockefeller Center, John D's temple to technology, towering above Saint Patrick's Cathedral.

Philanthropy Magazine

January 2011

Oil on Canvas

by James Panero

The Rockefeller family has long been one of the nations most generous patrons of high culture. Suzanne Loebl assesses its legacy.

When antitrust laws broke up the ice floe of wealth accumulated in Standard Oil in 1911, John D. Rockefeller Sr. became the richest man in the history of the modern world. His fortune was estimated to reach into the hundreds of billions in today’s dollars.

A devout Baptist, Senior believed in giving his fortune away as zealously as he earned it. Following John Wesley’s evangelical economics—“gain all you can, save all you can, and give all you can”—Senior used his vast wealth to support initiatives in education and medicine. He provided funds to turn the University of Chicago and Rockefeller University into world-class institutions. His philanthropy supported Baptist schools throughout the country, most notably in the rural South. His wife, Laura (“Cettie”) Spelman Rockefeller, had been an ardent abolitionist, and after gifts from Rockefeller she became the namesake of Spelman College, a college in Atlanta for black women.

Senior imbued in his descendants his own sense of philanthropic obligation. As the family’s wealth began to pass into the hands of his only son, John D. Rockefeller Jr. carried on the religious tenor of his father’s giving, while widening the mission to include America’s great temples of culture. In America’s Medicis: The Rockefellers and Their Astonishing Cultural Legacy, Suzanne Loebl takes up the story with Junior and follows the family’s cultural philanthropy through Junior’s last surviving son, David Rockefeller. The youngest of five prominent brothers—John D. 3rd, Nelson, Laurance, and Winthrop—David, now 95 years old, inherited his grandfather’s longevity and continues the mission of his parents into the 21st century. Readers will have to wait for the sequel to this book to read about the philanthropy of the fourth generation of Rockefellers, following the elevation of David Jr. to chairman of the board of the Rockefeller Foundation this past November.

With hundreds of books already published on the Rockefeller family, the story Loebl tells may not be new, but it is told well. Her work is a breezy guide for how the Rockefellers supported the arts and how, today, we continue to enjoy their cultural largess. She not only recounts their achievements; she also seems to rejoice in their artistic successes, like Junior’s Rockefeller Center, that pagan temple to technology, and shows regret for those initiatives that fell short of their potential, like Nelson’s Empire State Plaza in Albany.

Loebl locates Junior’s philanthropic beginnings in his religious maturation at Brown University, where he became a protégé of its president, Elisha Benjamin Andrews, a Baptist minister. There, he modernized his world outlook while retaining his sense of piety. Understanding the Rockefellers’ progressive Protestantism is key to unlocking the family’s philanthropy. Loebl could have even done more with it. No family has given so much while deliberately courting so little prestige. At Brown, Junior met his future wife, Abby Greene Aldrich, the daughter of Rhode Island’s senior Senator. (He also smoothed out his awkward social manner—no more lengthy audits of dinner checks or salvaged postage stamps.) Later on, his faith would continue to inspire his giving, even (perhaps, especially) when applied to secular cultural causes.

As Junior settled back in New York after graduation and joined the family business, he took up teaching the Young Men’s Bible Class at the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church, which later relocated to Park Avenue. Inspired by the great Protestant modernist Harry Emerson Fosdick—the brother of an influential trustee of the Rockefeller Foundation—Junior undertook the creation of a new ecumenical cathedral in Morningside Heights, eventually donating $32 million to the project.

Junior laid the cornerstone for Riverside Church in 1927. Designed in the Gothic style of Chartres, the cathedral could accommodate 2,100 worshippers. It was completed in just three years, despite a massive fire during its construction. Included in the building’s elaborate ornamental program are carved likenesses of Albert Einstein and Charles Darwin, signaling the church’s (and Junior’s) progressive stance in the controversy between fundamentalism and theological modernism. The 22-story clarion, with 74 bronze bells, which includes the largest turned bell in the world, is named for Junior’s mother. Fosdick served as its first senior minister, and the church continues to broadcast Fosdick’s left-liberal worldview—sometimes to absurdity. In 2000, Fidel Castro delivered a four-hour-long diatribe from the Riverside pulpit, just one example of how politics sometimes obscure the beauty of the church’s towering architecture.

In the decades to follow, Rockefeller money spread through an ever widening circle of cultural enterprises. The successful ones were extensions of Junior’s ecumenical spirit, even when they were secular projects. Freed from a literal interpretation of the Bible, his advancement of science, art, and technology could take on its own religious fervor. Of these institutions, perhaps no other has been more influential and more closely associated with the Rockefeller family than the development of the Museum of Modern Art, built on the grounds of the one-time family compound.

MOMA is the Rockefeller temple to modernity, with a reverential solemnity that continues to define the institution to this day. Loebl dedicates a large section of her story to MOMA’s development and its principal founding patron, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. Her husband, Junior, found little to like in modern art; his artistic passions were directed to sculpture, architecture, and Old World craftsmanship. Yet Abby saw her interest in modern art in Junior’s terms. “To me art is one of the great resources of my life,” she said. “I believe that it not only enriches the spiritual life, but that it makes one more sane and sympathetic, more observant and understanding, regardless of whatever ages it springs from or whatever subject it represents.”

The intricate dynamics of Rockefeller family giving could be comical at times, but they also served as lessons in how disparate tastes can play off each other to encourage greater developments. According to Loebl, Junior’s “dislike for some of modern art’s emotionally unrestrained, expressionistic spirit was such that the couple agreed that the art she acquired should be kept out of his sight.” At first Abby paid for her modest purchases, which formed a collection of thousands of modernist prints now in the MOMA collection, with Aldrich family money. In 1927, Junior increased her allowance of $50,000 for charitable gifts with another $25,000 for the art of her choosing. Abby sent her husband a formal thank-you letter, and Junior doubled the art budget the next year. Despite his aversion to its holdings, Junior proved to be MOMA’s single largest contributor by the time of his wife’s death in 1948. In addition to an initial $1.25 million, he donated another $4 million in her memory in the early 1950s. His sons, Nelson and David, later took up leadership roles at MOMA, donating artwork and millions more.

While Abby was founding MOMA in midtown, Junior went uptown, to the northern tip of Manhattan, for his greatest museum creation. As he did with his Riverside Church, which overlooks the Hudson River, Junior secured one of the most picturesque natural locations in the city for his creation—66 lofty acres around historic Fort Tryon, on a ridge north of the George Washington Bridge. He also bought up 700 acres of land along the Palisades in New Jersey to protect the viewshed across the Hudson.

The initial idea for bringing the fragments of disused ecclesiastic buildings from Europe to the United States belonged to George Grey Barnard, an eccentric sculptor. He imported columns and arches from four different cloisters, most notably the Benedictine abbey of Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa, before France tightened its laws on cultural exports. For a time he reassembled them as a small private museum on Fort Washington Avenue, not far from Rockefeller’s park property, which Junior donated to the city. Through Junior’s negotiations, the Metropolitan Museum was able to purchase Barnard’s architectural collection in 1925. Then with James Rorimer, the curator of the Met’s new Department of Medieval Art, and Charles Collens, the architect of Riverside Church, Junior reassembled the Cloister holdings into a unified building on a site reserved in northern Fort Tryon Park. The new Cloisters became the Met’s repository of medieval art, as well as one of the country’s great, unique architectural achievements. It also houses what was one of Junior’s most beloved possessions: the set of South Netherlandish Unicorn tapestries from 1495–1505.

Beyond these gems, few aspects of America’s cultural life have been bereft of Rockefeller largess. Loebl follows the story through the development of the Asia Society, Colonial Williamsburg, archeology museums, folk art collections, and the art of non-Western cultures. These have, of course, been a mere portion of the Rockefeller family’s entire philanthropic reach.

In the generation following Junior, the narrative of the Rockefellers’ cultural achievements gets harder to follow. There is an ever widening cast of characters. One also senses that the family’s ability to pull off great new cultural complexes gradually diminishes. Lincoln Center, John D. 3rd’s vital performing arts complex in Manhattan’s Upper West Side that includes spaces for the Metropolitan Opera, City Opera, the New York Philharmonic, the Juilliard School, and the New York City Ballet, is, architecturally, a brittle stepchild of Junior’s Rockefeller Center. Nelson’s redevelopment of downtown Albany into a massive governmental boondoggle, undertaken when he was Governor of New York, resembles nothing less than a fascistic parade ground cutting through the capital city.

Today the Rockefeller Foundation continues to support hundreds of cultural projects, but the heart of Rockefeller-style philanthropic fervor may have moved on to other causes. Maybe cultural philanthropy was but a generational stopover on the way to addressing more progressive political issues, ranging from global health to international relations and environmentalism. Politics also has a way of intruding in the arts. The Rockefellers found that out the hard way, when the family infamously commissioned Diego Rivera to paint a mural for Rockefeller Center. “Man at the Crossroads” ended up a paean to communism, featuring Vladimir Lenin, which Junior decided to remove. Fortunately, there are converts once the missionaries move on. With many hands now supporting them, the Rockefellers’ great cultural initiatives, from Rockefeller Center to MOMA to Lincoln Center, continue to thrive and enrich the life of the arts.