James writes:

Stephen Christopher Quinn is a naturalist and artist who joined the staff of the American Museum of Natural History, New York, in 1974, after graduating from Ridgewood School of Art and Design. He apprenticed under such diorama masters as Raymond deLucia, Robert Kane, and David J. Schwendeman. He is the author of Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History. I spoke with Mr. Quinn in early January in preparation for my 'masterpiece' column on the dioramas for the Wall Street Journal (available with permission here). For more about the dioramas, including images, a history, and video interviews with Stephen Christopher Quinn, visit the museum's new diorama website. Special thanks to Frank Winslow, editorial intern at The New Criterion, for transcribing this interview.

Stephen Christopher Quinn is a naturalist and artist who joined the staff of the American Museum of Natural History, New York, in 1974, after graduating from Ridgewood School of Art and Design. He apprenticed under such diorama masters as Raymond deLucia, Robert Kane, and David J. Schwendeman. He is the author of Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History. I spoke with Mr. Quinn in early January in preparation for my 'masterpiece' column on the dioramas for the Wall Street Journal (available with permission here). For more about the dioramas, including images, a history, and video interviews with Stephen Christopher Quinn, visit the museum's new diorama website. Special thanks to Frank Winslow, editorial intern at The New Criterion, for transcribing this interview.

James Panero: Hello, Stephen. Thank you for agreeing to discuss this marvelous new book with me today.

Stephen Christopher Quinn: Hello, James. I’m happy to. Thank you for having me.

JP: Does one diorama stand out as a masterpiece above all others?

SCQ: I think you would have to say the mountain gorilla diorama, perhaps the whole African family. It’s artistically and historically, I think, the greatest habitat diorama in the world. It’s such an icon among American museums. There are others that are wonderful artistically for different reasons, but in that one diorama, there are so many really compelling stories. Carl Akeley’s efforts to save the gorillas, and his success, just make it a wonderful exhibit.

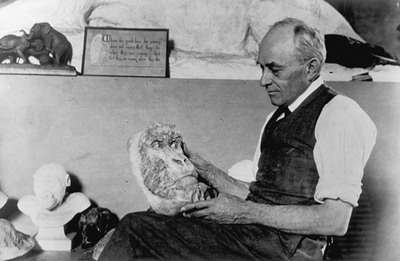

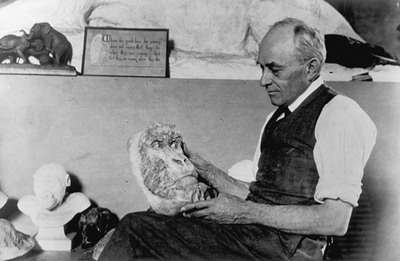

Carl Akeley contemplates a plaster mask impression taken from one of his gorilla specimens during his 1921 expedition to Africa (c.1924)

Carl Akeley contemplates a plaster mask impression taken from one of his gorilla specimens during his 1921 expedition to Africa (c.1924)

JP: It’s an incredible story. There’s so much it has to tell. If there's one flaw in my opinion, it's with the background painting by William R. Leigh.

SCQ: You’re absolutely correct. It sounds like you’ve been studying my dioramas. I think that if you were to make your decision solely on aesthetics, you would inevitably fall to one of the dioramas done by James Perry Wilson. That’s because there is no other background painter who was able to capture such a sense of place or of real elation or of a real site as James Perry Wilson.

Jaguar

Jaguar

Hall of North American Mammals

JP: Do you have any personal favorites?

SCQ: Hmm…I’m not sure. I probably do have a couple of favorites. I do love the Jaguar diorama.

JP: The setting is incredible.

SCQ: It’s such a good scene, too. It takes such courage on the part of an artist to paint a sunset and not have it appear smaltzy, and Wilson was so thorough in his studying the physics of light and how light changes in the sunset that he portrayed it perfectly. And he scaled down the values in the landscape portion of the painting so the sky would really sing in contrast. It’s such a powerful image with the jaguars looking off the rock ledge down into the valley.

JP: It’s a beautiful assembly.

SCQ: Yes it is. Do you know the one I really love? It’s the coyote in Yosemite National Park. It’s a smaller diorama, but in that one the sky is a cloudless blue sky, and there you see the amazing talents of Wilson in blending and mixing blues from the zenith down to the horizon line. He would divide the sky, mix his paints, and blend with a large badger hair, stippled rush blend from the zenith down to the horizon line and get a perfect gradation of sky tones. It just creates a perfect sense of atmosphere in that one as well.

The other thing that’s wonderful about the coyote, in the sense that it is a relatively small diorama, is that you’re only three or four feet from where the foreground, this rocky beach, merges with the background painting. And it’s flawless! It’s as close as you can get. Your eye is led back into the painting and into this illusion of three dimensional objects merging into a two dimensional painting. It’s really wonderful.

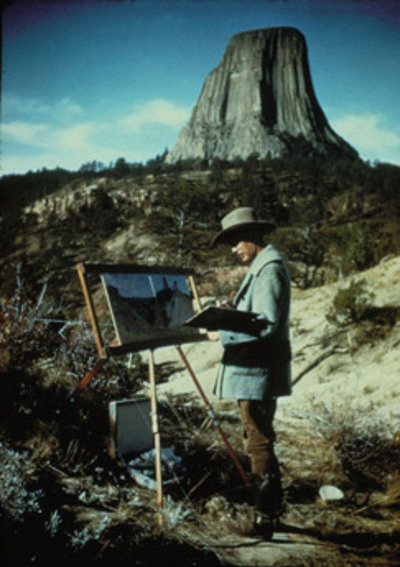

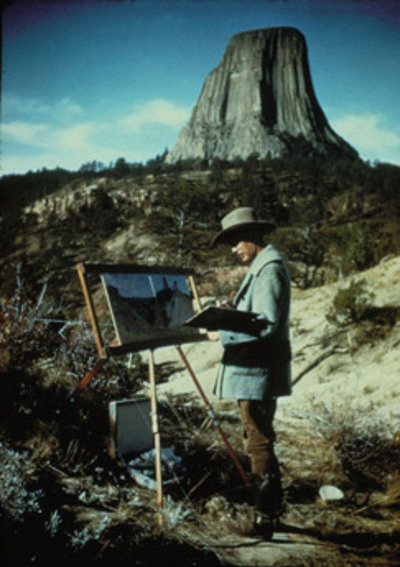

James Perry Wilson field sketching at Devil's Tower, Wyoming (1942)

James Perry Wilson field sketching at Devil's Tower, Wyoming (1942)

James Perry Wilson sketching Devil's Tower for the mule deer diorama, with the scale model and his field sketch in the foreground (1942)

James Perry Wilson sketching Devil's Tower for the mule deer diorama, with the scale model and his field sketch in the foreground (1942)

JP: So would you say that Wilson was the most innovative background artist to work at the museum?

JCQ: I think so. In the book we talk about his method, his art of concealing art. He saw it as his mission not to create subjective interpretations but real, objective records of nature. He felt that was appropriate in the science setting, yet he was a painter. The great thing about Wilson is that if you have a chance to visit the museum with binoculars, you can see that he really did paint the backgrounds. They’re not photorealistic at all. If you climb into the dioramas and inspect the paintings closely, they’re painted to be viewed, outside the groove, about three foot from the dead center in front of glass.

When you view them with binoculars, you can see that his paintings are really quite loose. For instance, his painting of the plains diorama, The Serengeti plain diorama with the African mammals, depicts vast herds of wildebeests, zebra, and giraffes off in the distance. They look beautifully rendered off in the distance, but when you look at them with binoculars, you can see they’re just little blips of paint on the background. So, though he was very accurate at rendering the environment, when you get inside the grid, he was very painterly.

JP: He was a magnificent artist.

JCQ: Yes, definitely.

JP: Are there specific elements of certain dioramas that you feel best reflect the art form at its most masterly? Who are the best taxidermists, foreground artists, and background painters? Could you give me specific examples of each?

JCQ: Master of the foreground artists? Wow. That would be a tough one. I think certainly Raymond deLucia stands out as a master. George Peterson stands out as a master of botanical models. Probably the master of all taxidermists of big game—I would even push him on a level that in some ways may surpass Akeley—is Robert Rockwell.

JP: Rockwell’s work is everywhere in the museum. It's incredible.

JCQ: Yes, it’s monumental animal sculpture, nothing short. He mounted over a hundred mammals during his stay here at the museum. He was quite prolific.

Alaska Moose

Alaska Moose

Hall of North American Mammals

JP: Do you ever regret the background of the Moose diorama, painted by Carl Rungius?

JCQ: No, actually, I don’t. I really love Carl Rungius’ wildlife paintings, and I think it’s a nice contrast to Wilson directly across the hall. It’s a perfect place to make comparisons and to point out the fact that ideally dioramas should depict flawless science rather than art. At the same time, I think the Muskeg environment, the Autumnal colors, and the way Rungius has painted that in the broken color—it’s apparent that he was more comfortable, obviously, as an easel painter than he was painting on a curve. That’s very apparent.

Just look at the sky for example, the sky tends to wrap around. The cloud patterns accentuate the curve; rather than, if you turn and look at Wilson’s, the big cumulus clouds recede back and almost facilitate the big holes in that curve. For Rungius, that was a challenge for him.

JP: There's some debate whether Rungius finished his moose background.

SCQ: Yeah, I think it is up in the air. I would almost tend to think that it looks like a finished Runguis to me. It was structurally painted, the broken color approach, big planes and shapes and forms. And if you look at his easel paintings, they look very similar.

JP: Who was overseeing the dioramas construction during that time period?

SCQ: By that time it was James L. Clark who had become the Director of Preparations, as it was referred to at that time, which today has become the Exhibition Department. James L. Clark was himself a superb naturalist, taxidermist, and sculptor. Often times a design and lay out, the composition, was worked up in the field and brought back as a scale model and then approved by the larger art and science team back here at the museum.

JP: I find the pathos in a number of the dioramas of the North American mammals hall to be the most compelling in the museum. Would you agree with that?

SCQ: I think so. My own feeling is that the Akeley Hall, of course, is a grander space architecturally. That opened in 1936. All of the talents, all of the staff and techniques and methods and tricks of the trade that were utilized in the Akeley years were then brought to bear on the North American mammals groups, and I think that’s where you see the museum’s finest dioramas. The level of detail in terms of botanical models, and also that’s where Perry Wilson reaches his height in terms of developing his methods for using stereoscopic slides and mathematical grids for compensating for the distortion of painting on a curve.

So I really think that your inclinations there are correct. The North American mammals are superb. There’s another great diorama in that whole, and it’s a tiny one, the exhibit that features Ship Rock. It’s a little mammal called the ringtail, or cacomistle, and a striped skunk. It’s this great, monumental, rocky peak, and it’s catching the late day light. And Mesa Verde is in the distance and pinkish light. It’s just spectacular. The whole composition is wonderful. You can’t really break out the background painting from the foreground or the taxidermy, because they were carefully developed and designed as a unit.

Akeley Hall of African Mammals

Akeley Hall of African Mammals

© Akeley Scott Frances

JP: In the African hall, the dioramas often seem to depict a moment just before the action takes place. Like Renaissance statuary in contraposition.

SCQ: Exactly! You have the featured animal, which is often a noble, classic pose standing before the background painting with accessory plants. But in North American mammals, you have this real attempt to stimulate a time of day, to experiment with shadows merging with the background painting, to tell a larger story about behavior. I think North American mammals—a perfect example is the wolf diorama—these great dry color shadows on the snow, the whole use of footprints in the snow, wolf tracks verses deer tracks to tell the predator / prey story. All kinds of things are played around with, various night scenes in the North American mammals, all the raccoons and things like that, that are just really clever.

Canadian Lynx and Varying Hare

Hall of North American Mammals

JP: I've always been facinated by the Lynx and the Hare diorama.

SCQ: Very interesting. That’s a nice one. It’s beautiful. I was here when Ray deLucia restored that one. He had to build scaffolding over the top of the whole landscape so that he could access and remove all the old snow and replace it with clear, clean, white acrylic. He first created all the drifting effects with cotton batting.

JP: So was the snow original to the diorama?

SCQ: It was. It was done first by Charles Tornell, and then Ray deLucia got in there and restored it. The snow started to discolor.

JP: I think the snow still looks a little yellow compared to the background.

SCQ: Yes. The thing is the acrylic responds to ultra-violet light. And as much as we shield the UV lights with filters, the acrylic still breaks down to a yellow. So the snow scenes do require regular restoration.

JP: The theater of the scene is captivating. You look down through that little tree and see the hare. I think it’s an interesting piece for kids. I responded to it quite a bit when I was a child. When you’re that age, you see the scene at a much lower level, so you seem to relate more to the hare than you do to the lynx.

SCQ: I think that one has great theater. That’s perfect for kids. You always see children down looking underneath that evergreen.

JP: [laughs] So do the dioramas come alive at night?

SCQ: Oh, you bet!

JP: They do?!

SCQ: Absolutely. Absolutely.

JP: With everything from music videos to movies (The Squid and the Whale, Night at the Museum), this seems to be the moment when the museum dioramas have reached a new level of popular consciousness. Why do you think that is? Are we interacting with the dioramas in a new way? Since many of us view these dioramas first as children, do you think this renewed interest in the dioramas has been driven by nostalgia or something else?

SCQ: When I started in 1974, there was not a single computer in the whole building, and now, of course, all of us spend our lives tapping away at computers and working on computers. Of course at that time, the interactive technologies and virtual reality technologies were just getting under way. All museums were making every effort to be on the cutting edge of these technologies and trying, as best they could, to develop new technologies. The dioramas at that time were kind of viewed as dinosaurs and as part of the museum’s past. But as time has advanced, just in my tenure here, it has become increasingly apparent that the diorama provides an experience that other exhibit mediums can’t: a recreation of a real place, in real time, in full scale, where you really feel you’re encountering wild-life and nature. I think there has also been a recognition of the unique art, this unique application of art in the service of science using very unusual techniques in the creation of dioramas. So they’ve moved from simply exhibiting props, used to teach and educate, into the realm of fine art as well. I think that has given them new value. Since the museum has recently been viewed not only as one of the great scientific institutions, research facilities, and as maintaining the greatest collections of natural history objects in the world, it is also now considered one of the great art museums.

JP: Do you think that people after having read your book may be more willing to see the dioramas as works of art?

SCQ: I think that has been a real eye opener for folks. You know everyone comes to the museum to see the real thing, to experience the real thing, rather than an image or read about it in a book or access it online. And dioramas are a unique art form. They aren’t real. They’re an illusion. They’re so based in science and so disciplined in science that they do create a natural scene, a compelling sense of a place, and I think since they predate modern photography and television, many of them could be considered an early form of virtual reality. They were designed specifically to nurture public awareness of the environment and species loss, so they’re great, powerful tools. I think we respond to them the way we do to great art, and it’s a real response of heart and mind. We love those images and respond to the natural world.

JP: How long have you been working on your book?

SCQ: Active writing for five years, but prior to that, as you can imagine, being a young artist in the exhibits department, every coffee break, we’d sit there and listen to the stories of the old timers trips to Africa and to the West collecting exhibits. All these details were fascinating. I started to record them and write them down, soon after I started work. The one thing that I noted was that the background painters weren’t identified, so I started the archives on my own time, lunchtimes or whatever, and finally pulled together a directory of all the background painters in the museum.

JP: But isn't there a list of the diorama artists posted in the North American hall?

SCQ: Yes. That was one of the rare halls in which all of the artists were identified. But over the years there were probably over two hundred dioramas in the museum when you consider not only the habitat dioramas but the anthropologic ethnographic scale dioramas. There was no one list. I was able to identify the background painters and circulated that among certain museum staff. There was such a good response to that that I started thinking about going back into the archives and finding the taxidermists, etc.

JP: So there was no master list at all?

SCQ: No. If you look at the back of the book, there is a directory to both the halls and the artists who worked on them, and it was going back into the archive and looking for that material that really spawned the idea of the book. I’ve got to say that I’ve been working on it almost my entire career at the museum. It’s a relief finally having it published and out there. It’s been a thrill. I didn’t think it would ever get the response that it has.

Now again people are realizing the powerful tools the dioramas have been over the years. They were really instrumental in creating legislation to preserve and protect the wildlife. They’ve been involved in the creation of national parks. And they really do function primarily as great tools for environmental awareness.

Since they do feature real places, I think there is a fascinating potential to go back and visit each site and to see these locations. I’m sure there would be some big surprises. We know there are specific dioramas in which our own species’ ecosystems have been degraded. And it would be wonderful somehow to revisit the other locations see what’s changed.

JP: Have you been to any of the source locations in which the dioramas are set?

SCQ: I’ve been to the gorilla diorama in Rwanda before all the trouble in the ‘80s. And, of course, the one big, steaming volcano in the background, Nyiragongo, has blown its top. Now there’s a great big caldera off in the valley. The thing that is very apparent at that site is the fact that the rain forest and forested areas have been cut and rendered for agriculture. There is a very apparent ring where the agriculture stops at the park border. It’s very apparent in that region the pressures of the human population and agriculture on the region.

JP: How close to the spot in the diorama is Akeley buried?

SCQ: There is a tomb that has been restored. It was vandalized and opened during the 1960’s. But I understand it has now been restored. I haven’t been there myself. But I believe it is very close to the site where the big silverback is standing, with that view. That site on the side of Mt. Mikeno was in Zaire, which is now the Democratic Republic of Congo I believe. The park expands now three countries: Rwanda, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The tomb is cast concrete with Akeley’s name in relief. It was cast by the expedition team, a Richard Raddatz was one of the technicians and foreground artists on the expedition who worked with the expedition members to create this concrete tomb and cover lid for it. It’s my impression that it is still there. I believe the museum archives does still have a photograph.

JP: What is the most rewarding part of your job?

SCQ: I think it’s great to have a job in which you feel you’re working toward a noble purpose and that is science, education, environmental awareness, and an awareness of cultural diversity. Working here at the American Museum of Natural History gives you that feeling. I think it’s always been a real thrill to utilize art as a medium for environmental education and teaching science.

JP: Thank you very much for your time, Stephen. It’s been wonderful talking with you.

SCQ: It was my pleasure, James. Thank you.

THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW