Moon Jar, Early 18 century. Porcelain, Height 16 1/8 inches (41 cm). National Museum of Korea, Seoul. Treasure No. 1437.

HUMANITIES

Spring 2014

The Unknown Korea

by James Panero

Little known treasures from the Joeson dynasty come to the United States

“Sacrifice,” writes Lee Myung-Bak, the former president of South Korea and CEO of Hyundai, in his autobiography The Uncharted Path. “That's what makes our mosaic so beautiful and rich.” Over the last sixty years, such sacrifice has turned a war-torn country into an economic powerhouse and brought what is known as the “Miracle on the Han River” to the United States. We Americans drive Korean cars, eat Korean cuisine, watch K-Pop on Korean electronics, and read Korean-American literature by celebrated writers such as Chang-Rae Lee.

The confident reach of South Korean culture follows that country’s emergence from a century of terrible upheaval, in which it was caught up in the territorial ambitions of China, Japan, and Russia as well as the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. Over a million people perished in the Korean War between 1950 and 1953. And today, even as South Korea has emerged from darkness, North Korea remains captive to an aggressive tyrannical regime.

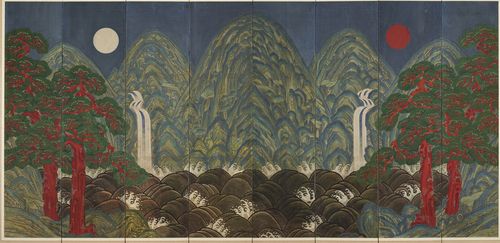

Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks, Artist/maker unknown, Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), 19th century, Eight-fold screen; colors on paper, 82 11/16 × 217 7/16 inches (210 × 552.3 cm), Private Collection

For Hyunsoo Woo, curator of Korean art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the moment was right to look beyond her country’s recent past to the era that informed it: the 518-year reign of the Joseon Dynasty (pronounced “Choe-sun”), from 1392–1910, which gave Korea its culture of duty. What has resulted is an ambitious survey of one hundred and fifty works called “Treasures from Korea,” now on view at the Philadelphia Museum, an exhibition that will travel on to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

The show is a “dream come true,” Woo tells me over lunch at the museum. “Everyone thought I was crazy.”

Crazy, in part, because of the difficulty in securing work for such a show. There is relatively little Korean art in American museum collections. “The number of Korean pieces in the United States is drastically smaller than for other Asian art. There is much less of it than Chinese or Japanese,” says Woo.

Portrait of Yi Jae (1680-1746), Artist/maker unknown, Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), Late 18th century, Hanging scroll; ink and colors on silk, 38 1/2 × 22 3/16 inches (97.8 × 56.3 cm), National Museum of Korea, Seoul.

Known as the “Hermit Kingdom,” Korea under the Joseon was late to open its doors to the West. Korea only began normalized relations after establishing a trade treaty with the United States in 1882. “Korea didn’t know about the rest of the world,” says Woo. By 1890, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston already had a curator for Japanese art, and American collections of Japanese and Chinese artifacts were extensive. Even today, according to Woo, there are only four curators for Korean art at U.S. museums, and until recently only UCLA offered a Ph.D. program in Korean art history. As a result, Americans know sadly little about Korean art.

Joseon art and artifacts are rare in Korea, too, and are seldom lent overseas. “We went through a rough modern era: the annexation by Japan and the Korean War between north and south. The whole country was completely ruined,” says Woo. The upheaval led to the “loss of many treasures and cultural properties,” and some that did survive remain locked away in North Korea. What survives in the south can also be fragile: paper, hemp, silk. Woo’s only choice for a multicity exhibition was to find different objects to borrow from Korea for each location: “We are only allowed to show one painting at any venue, for conservation reasons. So it was extremely complicated. Books and paintings will all be rotated. Screens are on paper and silk.”

Ever since the war, in which 40,000 U.S. service personnel lost their lives or went missing in action, America has had a deep bond with South Korea. So “Treasures from Korea” grew from the spirit of cultural exchange between the two countries—and became far more expansive than even Woo first envisioned. In exchange for the loans from Korean institutions, many of them protected as national treasures, the three stateside venues, plus the Terra Foundation for American Art, first lent a historic three-century survey of their holdings for an exhibition called “Art Across America,” which showed in 2013 in Korea at Seoul’s National Museum, a key organizer of the current exhibition.

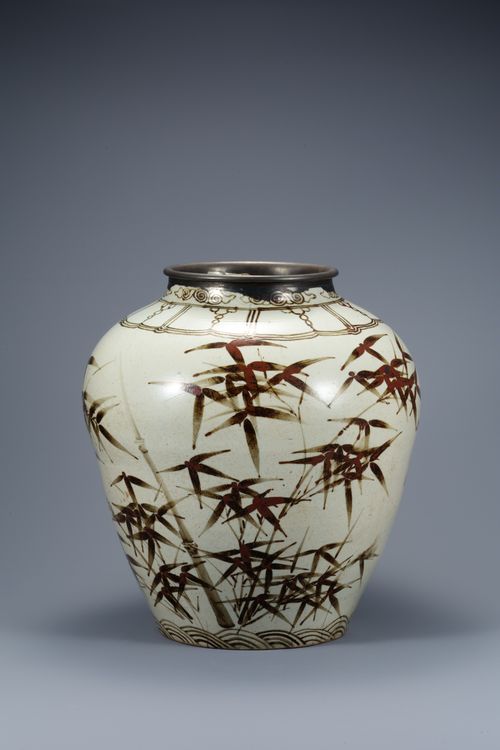

Jar with Design of Bamboo and Plum Trees, 16th to 17th century. Porcelain with underglaze iron decoration, 15 3/4 x 14 15/16 inches (40 x 37.9 cm). National Museum of Korea, Seoul. National Treasure No. 166.

Just as Koreans might be familiar with Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol, but new to the Hudson River School, the art and culture of the Joseon will be an eye-opener for American audiences. The word “treasures” brings to mind rich materials, but the Joseon, the longest reigning neo-Confucian dynasty in history, enforced an austere aesthetic. “Reserve, discipline, formality, simplicity, serenity,” says Woo of the Joseon. “It was a great culture of recording.” Its respect for tradition and self-sacrifice helps explain its singular longevity. Imported from China, neo-Confucian scholarship also gave Korea’s intellectual class a way to keep its monarchs in check.

The art of the Joseon was far more spare than what you see from earlier Korean dynasties, such as the Buddhist Silla. Pronounced “Shilla,” works from this period were recently exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Highlights of the Joseon include minimalist porcelain pottery, often left white and unadorned, and the detailed scrolls used to record and dictate royal ceremonies. “Japanese and Chinese art, if you look at it, you think, amazing, gorgeous, look at the level of technology and achievement,” says Woo. “But with Korean art, you don’t really have it. It takes some time to appreciate. That’s where the challenge is. There is no immediate response to it.”

Instead, Joseon art rewards close looking, with small imperfections, a fingerprint left here and there, revealing the soul behind the austerity. “There is a huge jar. A moon jar,” Woo explains of one large example from the early eighteenth century. “And it is really a difficult technique to perfect . . . because the diameter is so wide.” The same goes for the dynasty’s detailed, illustrated self-documentation, one that in a way mirrors our own “selfie” culture.

Military Costume (Dongdari), 19th century. Silk, length: 45 11/16 inches (116 cm). Dangook University Seok Juseon Memorial Museum, Yongin.

“We wanted this to be a great introduction to Korean art,” Woo says of her exhibition’s thematic approach, which ranges from sections on the royal family to dioramas of simple Joseon rooms, clothing, and everyday artifacts. “So we wanted to do the exhibition that way, to come up with some themes, to come up with some story based on the viewer’s own knowledge.”

The screen paintings, Woo’s academic specialty, take little to appreciate: Often symmetrical landscapes in gorgeous geometric patterns, filled with naturalistic symbolism, they were used as royal backdrops and objects of prestige. The exhibition’s innovative digital displays do an impressive job at unpacking and explaining the messages in these paintings. “We really wanted to integrate that technology to broaden the knowledge,” says Woo. “Because we knew that Korean art and Korea in general are new.”

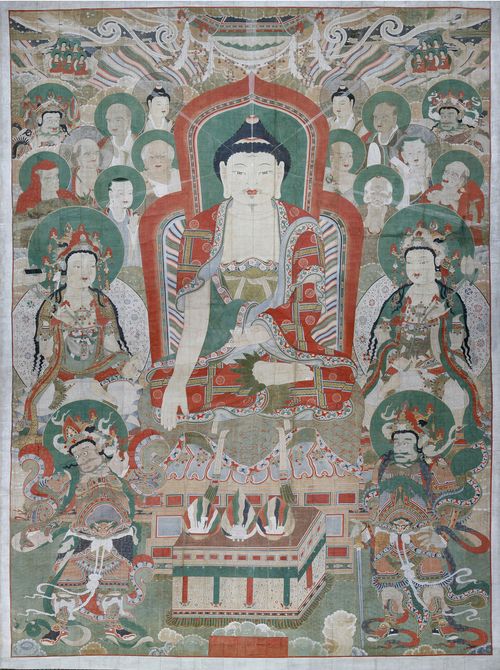

Śākyamuni Assembly, 1653. Hanging scroll; colors on hemp, 39 3/16 × 25 7/16 feet (12 x 7.8 m). Hwaeomsa, Gurye. National Treasure No. 301.

The biggest surprise, now at the Philadelphia Museum, is certainly the Śākyamuni Assembly, a thirty-nine-foot-tall hanging scroll of the Buddha, painted on hemp and used for outdoor services, from 1653. The fact that this towering object even made it to Philadelphia is astonishing—it is far too large to travel to the other venues. Woo had the vision of it hanging in the museum’s Great Stair Hall, where the statue Diana by Augustus Saint-Gaudens is otherwise displayed. “When I first told people that I really wanted to bring that painting here, everyone thought it was impossible. And I thought my chances were extremely slim because of its size, and it is designated a national treasure of Korea. There are about eighty paintings of that type that survived in Korea at different temples, and, among those, this is the best example in terms of size, quality, condition, and date of production. This is one of the earliest.”

Yet, Woo says, “along the way, people became convinced it was important to show because it was never introduced outside of Korea.” The transportation of the scroll by cargo plane from Korea to Philadelphia was a feat in itself, and the complex image, now in line with the axis of the museum’s grand east entrance and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, is breathtaking.

The lavish scroll hints at another side of Joseon culture. Beneath the asceticism of the dynasty’s official neo-Confucian mandates, a more fanciful Buddhist influence from earlier dynasties never went away. The same might be said of the two-part nature of Korean society today, with a fanciful pop culture that overlays a deeper, older mandate. “The spirit, the Confucian ideals,” says Woo, “you have to pay ultimate loyalty to your king and the state. Even in the current day, we see that. You put your family, your organization before you.”

In the north, we see a regime’s repressive interpretation of the old Hermit Kingdom. In the south, a Confucian work ethic drives the country’s exuberant contemporary culture. It has also brought a divided nation back from the brink. “When I was growing up, I rarely saw my father,” says Woo, “because he was working so hard, building the country.” During the war, she explains, he fled from the north at fourteen, leaving family behind. “He thought he would only be away for a few months. Now it has been sixty years.” Woo’s “Treasures from Korea” honors all those who have made the sacrifice to ensure the survival of this treasured culture.

Ten Longevity Symbols, 18th century. Ten-fold screen; colors on paper, 98 7/16 × 231 1/8 inches (250 × 587 cm). Private Collection.

The traveling exhibition “Treasures from Korea: Arts and Culture of the Joseon Dynasty: 1392–1910,” originally on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, will be on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art from June 29 till September 28 and at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, from November 2 till January 11, 2015.