THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

June 28, 2015

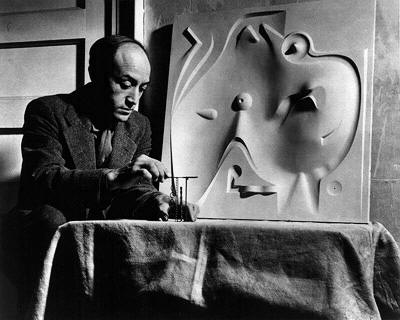

Noguchi

by James Panero

A review of LISTENING TO STONE: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi, by Hayden Herrera, Illustrated. 575 pp. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. $40.

The art of biography is not unlike the creation of sculpture. Out of a raw material of artifact and anecdote must emerge the semblance of living form. There may be no one right way to animate such matter. Certainly, there are plenty of wrongs: from hazy abstraction to overwrought realism, from misapplied attention to mannered application. Whatever the approach, however, the spirit of the subject must somehow guide the telling. For Isamu Noguchi, the great border-crossing sculptor of the last century, the art came, he said, from tapping into “the materiality of stone, its essence, to reveal its identity — not what might be imposed but something closer to its being.” The genius of “Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi” is how its author, Hayden Herrera, inhabits the sculpturing hand of its subject. Rather than focus on the surface, Herrera gets “beneath the skin,” as Noguchi would say, to the “brilliance of matter.”

In Herrera’s elegant account, the “stone” of Noguchi’s “art and life” is left quiet enough for us to hear. Distracting voices, whether they be the author’s or those of Noguchi’s many friends, lovers and critics, are kept to a minimum. The story that emerges is therefore not unlike one of Noguchi’s gardens, or his playground designs, or his dance sets. Space and spareness balance matter and articulation. “An important element in both Japanese stroll gardens and Noguchi’s sets was the experience of the body moving through space,” Herrera writes. Arranged along the path of Herrera’s chronology, Noguchi’s words and deeds similarly convey their affinities without overly determining one step to the next. “If sculpture is the rock,” Noguchi once wrote, “it is also the space between rocks and between the rock and a man, and the communication and contemplation between.” Both artist and author leave room for us to drift around and listen.

The writer of biographies of Frida Kahlo and Arshile Gorky, two artists who make intimate appearances in this latest work, Herrera understands creative people. In Noguchi she follows a life that rarely departs from the realm of artistic mythology. Noguchi’s Japanese father, Yone, was a rising poet living on Manhattan’s Riverside Drive. He met Isamu’s American mother, Leonie Gilmour, through a classified ad he took out for freelance editorial work in 1901. Following their brief affair, he returned to Japan. Yone bequeathed his name and poetic sensitivities to his son but withheld just about any other consideration one might expect. “He appears to have had little regret at leaving the six-months-pregnant Leonie behind,” Herrera writes.

Because of his father’s fame, Isamu’s birth in 1904 elicited a newspaper headline in Los Angeles, where Leonie came to live in a tent town: “Yone Noguchi’s Babe Pride of Hospital. White Wife of Author Presents Husband With Son.” The remarkable article foretold much of what Isamu would contend with in life: his estranged father, his Japanese and white-American backgrounds, and the public recognition he would attain by giving form to mixed identities. This forming took shape as a continuous process over Noguchi’s long creative life, beginning with himself. “After all, for one with a background like myself the question of identity is very uncertain,” Noguchi said in 1988, the year of his death. “It’s only in art that it was ever possible for me to find any identity at all.”

Noguchi’s mother became the sculptor’s “strongest influence.” Far more than his father, it was his mother, a fascinating and tragic figure, who haunted Noguchi’s expression, and she likewise haunts the pages of Herrera’s biography. “I think I’m the product of my mother’s imagination,” he once said. Leonie was a graduate of what became known as the Ethical Culture School, which stressed both “manual and academic training.” She followed this with a scholarship to Bryn Mawr College and studies at the Sorbonne. “She kept hoping I would eventually become an artist,” Noguchi said. She got her wish — but, dying of pneumonia in 1933 at age 59, never saw his artistic promise fulfilled.

In his formative years, as his mother attempted to reconnect with his father, Noguchi lived for a decade in Japan. Here he became “knowledgeable in the ways of nature” with “respect for materials and how things are made.” Leonie read Greek mythology to Noguchi while encouraging him to “learn how to build a Japanese house.” Then in 1918, she sent her 13-year-old son on his own back to America to study at a progressive hands-on school in Indiana. From then on, fortune and talent saw this self-described “waif” through artistic and spiritual mentorships that included studying Italian sculpture-casting at a school on Tompkins Square Park in New York and interning with Gutzon Borglum, the future creator of Mount Rushmore (who told Noguchi he would never be a sculptor). In Paris, an apprenticeship in the studio of Constantin Brancusi, a “laboratory for distilling basic shapes,” gave Noguchi his modernist bequest, to which he added a traditional Japanese sense for the “value of nonassertiveness.”

Just about every famous and interesting person of the 20th century seems to have crossed Noguchi’s globe-spanning path. Perhaps most significant was the futurist Buckminster Fuller, whom Noguchi called a “messiah of ideas.” At only two points did Noguchi’s associations touch down to earth. Patriotically American, denouncing the militancy of his father’s Japan, Noguchi voluntarily locked himself in a Japanese internment camp during the war. For a brief moment some years earlier, he also studied pre-med at Columbia University — news that his mother “hotly denounced.” She wanted her son to “be your own god and your own star.”

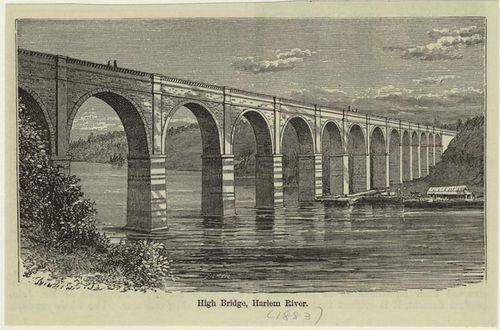

It was Brancusi who taught Noguchi “you’re as good as you ever will be at the moment. That which you do is the thing.” Noguchi could be as artistically astonishing in his portrait busts of the 1920s and ’30s, where innovative materials reflect the nature of his sitters, as in his enigmatic stone abstractions of later life. Just as he crossed borders, he crossed disciplines to work with others. Some of his greatest output came from these collaborations: dance sets for Martha Graham; garden designs with architects; his coffee table for Herman Miller; and his Akari light sculptures, the paper lanterns now universally copied, which came to overshadow his other work. Herrera’s book also tells how some of Noguchi’s most startling concepts were never completed: Robert Moses killed an innovative playground design for the United Nations; Thomas Hoving prevented another destined for Riverside Park. One hopes this last design, a collaboration with Louis I. Kahn, might still someday be realized, as we’ve seen with Kahn’s posthumous Four Freedoms Park on Roosevelt Island.

Rather than for a particular body of work, Noguchi said he hoped to be remembered for contributing “something to an awareness of living.” As a “magnificent gift to the people of New York,” Herrera writes, 30 years ago the artist created the Noguchi Museum out of his studio in Long Island City. To this legacy of awareness we can now add the present biography. Walking in his museum garden with his friend Dore Ashton, Noguchi once said, “I have come to no conclusions, no beginnings, no endings.” With minimal intervention, Herrera helps all of us walk beside this “nomad” who “sought and found, by making sculpture, a way to embed himself in the earth, in nature, in the world.”