"Embattled Garden," here performed by Lorenzo Pagano, Mariya Dashkina Maddux, and Lloyd Mayor of Martha Graham Dance Company; photo Christopher Duggan

How often should we expect the Martha Graham Dance Company to perform dances by Martha Graham? I might suggest something like 75 percent of the time. Founded by Martha Graham in 1926, here is the oldest dance company in America. Tasked with preserving and transmitting the repertoire of 181 works that Graham left behind at her death in 1991 at age 96, the company now offers the only means, for the most part, of seeing the dances of our most influential American on the modern stage. Yet over the finale weekend at Jacob’s Pillow Dance in Becket, Massachusetts, the number of Grahams by Graham stood at just 25 percent. Only one in four dances on the program was a Graham original, while the remaining work consisted of new commissions that ranged from the Grahamesque to the Grahamdiloquent.

Things started off well with Graham’s own “Embattled Garden.” Premiered in 1958, the dance reimagines the Garden of Eden as a fiery ménage à quatre among Adam, Eve, a serpentine “Stranger,” and Lilith, Adam’s first wife in midrashic literature. Explaining the program, Ella Baff, the Pillow’s Executive and Artistic Director, here celebrating her final season as head of the festival, called the work “vintage Graham” and jokingly asked, “Who needs reality television when you have high art?” She also reminded us of Graham’s own ties to the festival, since Graham herself had once studied dance at Denishawn with the Pillow’s founders, Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis, whose portraits flank the barn-like stage of the Pillow’s Ted Shawn Theatre.

There is an unmistakable “vintage” quality to vintage Graham. Today Graham dances can seem arch and overly expressionistic. Graham’s father studied mental disease, which might explain the epileptic quality to her movement that gets mixed in with long periods of stasis. Often, only some of the dancers are in motion on stage while the others strike a pose from the sidelines. Her music wasn’t always by the great Aaron Copland, either. For “Embattled Garden,” the bombastic score by Carlos Surinach is more MGM than Mahler. Its performance at the Pillow was made even worse by the recording, which sounded like a warped, out-of-circulation LP. (Without a live orchestra, dance in general needs to be mindful of the overamplification of recorded music.)

Despite these shortcomings, the set by Isamu Noguchi, unearthed from the Graham vault, was something else entirely that set the tone for the performance overall—a bold, tactile wonder unlike anything else now seen in dance. It was unmistakable Noguchi, just as this was unmistakable Graham—dance that seeks out the “communication and contemplation” (Noguchi’s words) between person and object. Color plays a bold role in the performance’s overall expression, something unfortunately missing from the black-and-white recordings that exist of Graham on stage, intensifying the mood and placing the work in an otherworldly, mythological light.

For this full effect we must see Graham in person, and at the Pillow, which I saw over a Saturday matinee, her Company delivered. Carrie Ellmore-Tallitsch as the haughty Lilith and Lloyd Knight as the slithery Stranger descend from Noguchi’s tree to vex Abdiel Jacobsen’s self-flagellating Adam while making a woman out of Mariya Dashkina Maddux’s Eve. “Martha always wanted to leave behind a legend, not a biography,” wrote Graham biographer Agnes de Mille. Here is a Graham legend of Biblical proportion.

Martha Graham Dance Company in "Depak Ine"; photo Christopher Duggan

Regrettably the next dance up, “Depak Ine,” choreographed just last year by Nacho Duato, attempted to take on its own “essential systems of being—of life, death, decomposition, and rebirth,” but lacked Graham’s modernist rigor. Instead we got smoke machines and mood lighting set to a techno beat. Mouth-pulling and other forms of pseudo-lunacy dominate this ponderous cirque du fou that only picks up at the eventual “rebirth” of dancer Ying Xin, who for a lifetime, it seems, had lain dead on stage.

Ben Schultz and PeiJu Chien-Pott of Martha Graham Dance Company in "AXE"; photo Morah Geist

The third dance, “AXE,” by Mats Ek, was a light pas de deux with more pas than deux, and almost worked. Commissioned by the Festival, the dance begins with the rear curtain opening to reveal what appears to be a wooden backdrop but is, in fact, the back wall of the Shawn Theatre. Pillow stagehands humorously deposit a pile of wood mid-stage—a task that would be prohibitively expensive should this ever be performed in New York under the work rules of Local One. Dancer Ben Schultz then gathers some big rounds from the pile, rolls over a chopping-block stump, lifts up his axe, and for the rest of the performance beautifully splits the rounds into wedges. The action of this dancer performing a manual labor recalls the history of the Pillow itself, as Shawn’s dancers helped build the original campus. Among the chopping, PeiJu Chien-Pott appears as a fluttering moth or woodsprite perilously unnoticed by the woodsplitter. The setup is great, but the engagement between the two never comes together—or splits apart like the wood under that axe.

Abdiel Jacobsen of Martha Graham Dance Company in "Echo"; photo Christopher Duggan

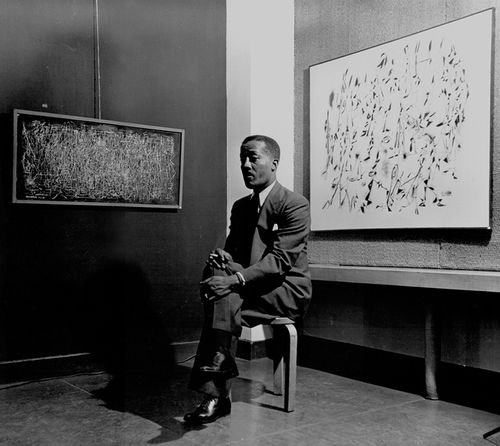

The final piece, “Echo” by Andonis Foniadakis, also from 2014, was the most successful of the program’s contemporary offerings. Foniadakis plays off the classical myth of Narcissus, who falls in love with his reflection, by using two male dancers, on my day danced by Lloyd Mayor and Lorenzo Pagano, as a mirrored pair. Pagano was especially engaging as the reflection, smirking and at times reaching out to Mayor’s Narcissus as though pulling him into the water. I found their engagement to be more memorable than the relationship between Narcissus and Echo, danced by Chien-Pott as the nymph who loves him but can only repeat what he says. Yet the corps was brilliantly deployed as blue ripples, spinning out Narcissus’s watery reflection in flowing skirts by Anastasios Sofroniou.

It could be argued that each of these three contemporary dances, based in myth, had a Graham-like component, but should they all be shown at the expense of Graham herself? After Graham’s death, the Graham Company went through a very public legal battle to gain control of her dances from her designated heir, nearly going out of business in the process. It would be a shame to think it was all destined for the Company vault. Under the direction of Janet Eilber since 2005, the Graham Company has followed what has become conventional wisdom in arts administration by actively pursuing new work. One may think Graham doesn’t fully translate to the world of contemporary dance. Without seeing more of her work on stage, we might never know otherwise.

Ted Shawn Theatre; photo Christopher Duggan