THE NEW CRITERION, November 2019

On “J. M. W. Turner: Watercolors from Tate” at the Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, Connecticut.

Sailing to Mystic Seaport is one of those prehistoric memories of my childhood that still inspires limbic delight. How primitive it all now seems: no cell phones or GPS, my father and I dead reckoning on our small cutter-rig Cape Dory. Down in the cabin, I measured the paper charts with a plexiglass navigational plotter. I turned the directional dials on the LORAN radio. Finally we reached the mouth of the Mystic River. We circled and honked our airhorn until the railroad and highway bridges rotated and lifted to let us through. When we tied up at the historic Seaport, a maritime town of preserved boats and buildings, the facility was just closing for the day. That was the best part about it. As transients staying overnight at the marina, we alone could still wander the Seaport village at all hours, past the cooperage, the ropewalk, the church, the tiny school, and the George H. Stone & Co. General Store, like Ishmael on his way to the Spouter-Inn. On my Walkman, I played a cassette tape of sea shanties. Here was the Age of Sail. We were living it.

From the Age of Sail—or at least its recreational variant—to the Age of Screen, the subsequent decades have not been altogether kind to Mystic Seaport. History has gone out of fashion, if you haven’t already heard. So has the sort of immersive history offered by institutions like the Seaport, founded in 1929, where reenactors forge iron, craft barrels, and caulk hulls in its historic structures. In our virtual present, real experience itself has grown suspect, foreign, even dangerous. As a teacher recently explained to me, many children today do not know what to do when their feet get wet. They really don’t know what to do when close-hauled in wine-dark seas. The sport of sailing has suffered. A large outdoor institution dedicated to our seafaring past has suffered especially.

Enter the “reimagined” Seaport. Since the turn of the millennium, the historic institution has proclaimed at least two “Strategic Plans.” The Seaport must be “repositioned.” It must “appeal to new audiences.” It must be “evolving and embracing contemporary culture.” It must be “rebranded.” It must be “relevant.” It all sounded, to me at least, quite alarming.

The Charles W. Morgan (middle), the last remaining American wooden whaling vessel, on the docks of Mystic Seaport. Photo: Mystic Seaport Museum.

Yet the distress calls have been a boon to the consultants, architects, and planners who now school around foundering institutions. One consequence has been the renaming of the Seaport, as it seems every “library” and “collection” and “institute” must be renamed these days, into a “museum.” And so we now have the “Mystic Seaport Museum.” Another consequence has been the construction of a new gallery, the Thompson Exhibition Building, to serve as a Kunsthalle for traveling shows and commissioned installations.

The proliferation of white-box galleries has largely become a blight on our cultural landscape. I suspect we will one day regret most of them, much like the benighted highways that slice through our urban centers, which are similarly designed for maximum throughput but have only invited further congestion. Contemporary art puts greater and greater impositions on its housing and display. Bigger galleries are built to contain it. Then new forms of art develop to overfill these gargantuan spaces.

Often this new art comes in the form of commissions designed to provoke commentary and commotion around some aspect of contemporaneity. At the Seaport we might soon see installations about swirling gyres, or modern-day pirates, or the rising seas. Or what about the history of the salt trade through large salt sculptures? That’s coming next year. You can almost figure it out yourself. The Seaport even brought in the impresario Nicholas R. Bell as its new curatorial director to crank up the institution’s popular reach, as he did at the Renwick in Washington, D.C., with immersive shows where “photography is encouraged.”

Museum leaders rarely lament these modern intrusions on their historic missions, buildings, and collections. Far from it—the “need” turns their hamster wheels. New buildings spur new fundraising that pays for more buildings and so on. What results are new brick-and-mortar (and glass-and-steel) billboards of perpetual presentness. I will never forget the director of one famous collection who proclaimed that her new Renzo Piano addition would finally let people know her institution was a museum. Of course, several generations of patrons managed to find their way there without Renzo. And of course, they still go there for the historic institution, not its mock-industrial appurtenance.

The Thompson Exhibition Building at the Mystic Seaport Museum. Photo: Mystic Seaport Museum.

Back at Mystic Seaport, maybe it’s the case of a stopped clock being right twice a day. Or maybe a favorable wind still blows over my beloved institution. Despite my dire predictions, through storm-tossed seas the Seaport has remarkably reached safe harbor. With a major exhibition of Turner watercolors on loan from the Tate, which opened here last month and remains on view through February, I might even say the institution has discovered a triumphant new world.1

Designed by Centerbrook Architects and Planners, the 14,000-square-foot Thompson Exhibition Building, which opened in 2016, is better than feared, even as it nevertheless presents a “distinct departure from the Museum’s traditional architecture.” Wood-framed in the shape of a hollow wave, the building references the Seaport’s collection of ship hulls in its fittings—although with its oversized patio and cavernous interior, the structure most resembles a mountaintop ski lodge. Stephen C. White, the Seaport’s president, says he wanted a building that would say, “Something’s happening here. Things are moving forward.” Such pathetic pleas aside, the museum sought a building that would be “good enough for Turner.” And here is Turner. There are also plans afoot to open up the Seaport’s extensive watercraft collection, with some eighty-seven boat designs, to public view. If this building boom ultimately leads to more open storage and more Turner, the results would be welcome indeed.

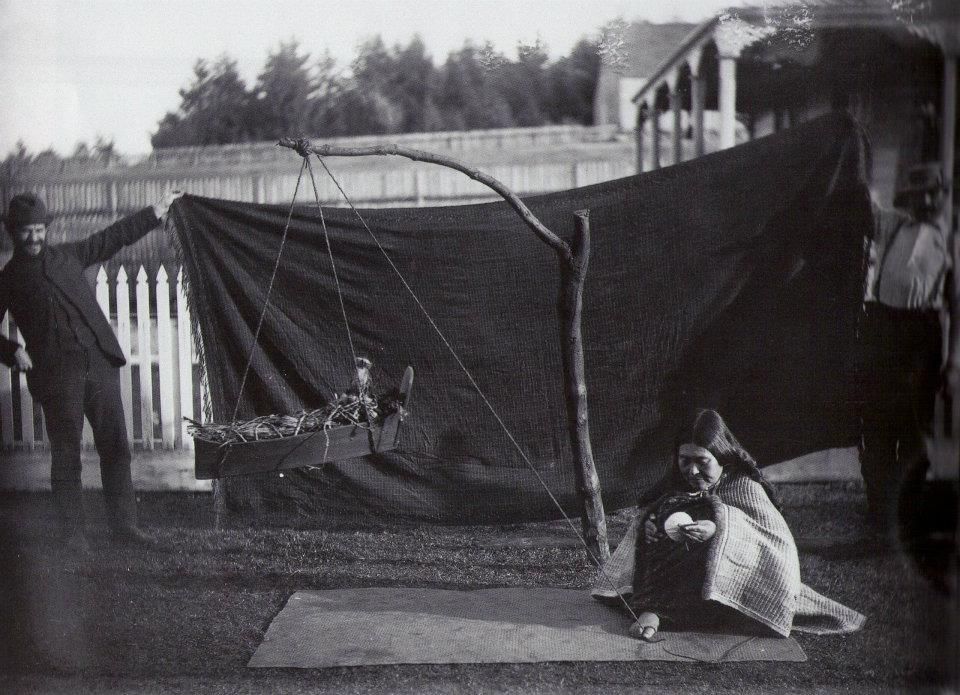

There is nothing quite like seeing a Turner, such as A Shipwreck in a Stormy Sea (ca. 1823–26), after just witnessing a reenactment of a nautical rescue by “breeches buoy,” as I did on my recent visit to the Seaport. The former United States Life-Saving Service, one of our government’s smartest creations, patrolled beaches day and night to rescue shipwrecked sailors. The breeches buoy was an ingenious system of ropes and pulleys that could be fired from a small cannon hauled down the beach from the lifesaving stations (which were themselves beautifully designed). Attached to the mast of a ship run aground, the buoy had a pair of shorts sewn to it that held passengers in place as they were hoisted ashore. Tens of thousands of lives were saved this way.

J. M. W. Turner, Whalers (Boiling Blubber) Entangled in Flaw Ice, Endeavouring to Extricate Themselves, 1846, Oil on canvas, Tate.

Through its artifacts and displays, the Seaport reveals the true challenges and terror of life at sea. Whaling ships like the Seaport’s prized Charles W. Morgan, the last remaining American wooden whaling vessel, were closer in experience to today’s floating oil rigs than to the romantic visions they might now inspire. They were factories at sea. American ships like the Morgan were the first to be able to harvest, process, and store whale oil, all without touching land, due to their set of shipboard try pots, which could render blubber while underway. “Voyaging in the Wake of the Whalers,” an ongoing and must-see exhibition at the Seaport, explains it all while matching a historic film of whaling with passages from Moby-Dick. Whalers (Boiling Blubber) Entangled in Flow Ice, Endeavouring to Extricate Themselves (1846), a stunning Turner painting at the center of this exhibition of watercolors, likewise shows those boilers firing away even as their ships sit stranded. Like a real-world Ahab, the American whaler was always determined.

While the watercolor exhibition is centered around a selection of maritime images, this is more than a “Turner and the Sea” show. The exhibition brings to America close to one hundred works from the Tate’s 1856 Turner Bequest, which ended up conveying just about everything the artist left behind, hook, line, and sinker, into Britain’s public trust. Selected out of some thirty thousand watercolors and sketches by the Tate’s David Blayney Brown, the exhibition presents the full arc of Turner’s astonishing fecundity. The artist began as a precise draftsman in such works as View of the Avon Gorge (1791), Durham Cathedral: The Interior, Looking East along the South Aisle (1797–98), and Holy Island Cathedral (ca. 1806–07). He ended up the atmospheric dreamer we famously know in such meditations as Venice: Looking across the Lagoon at Sunset (1840), Rain Falling over the Sea near Boulogne (1845), and Stormy Sea with Dolphins (ca. 1835–40).

J. M. W. Turner, Venice: Looking across the Lagoon at Sunset, 1840, Watercolor on paper, Tate.

The exhibition makes the compelling case that watercolor was the medium in which Turner developed and tested these stylistic innovations. An accompanying catalogue of revealing essays and interviews assembled by Bell (who will soon be leaving the Seaport) looks at how Turner began his career as a painter-like watercolorist and ended up a watercolorist-like painter. In resplendent works such as Venice: San Giorgio Maggiore—Early Morning (1819), we can see how Turner’s uncanny sense for luminosity on canvas first developed in the white ground of watercolor, as did his gauzy building-up of scrims and layers.

Water gives and it takes. In his 1950 book The Enchafèd Flood: or, The Romantic Iconography of the Sea, W. H. Auden writes that the sea represents “that state of barbaric vagueness and disorder out of which civilization has emerged and into which, unless saved by the effort of gods and men, it is always liable to relapse.” In his watercolors, Turner likewise mixed the waters of content and medium for his own deep dive into compositional disorder.

J. M. W. Turner, Arundel Castle, on the River Arun, ca. 1824, Watercolor on paper, Tate.

But Turner was not a pure abstractionist, despite the claims made by “Turner: Imagination and Reality,” Lawrence Gowing’s 1966 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that has long left us with an unfair retrospective view of Turner’s achievements. Nor was Turner a proto-Impressionist, an ultra-Romanticist, an anti-Industrialist, or whatever other school or cause he has been attached to. Turner began as an empiricist. As his compositions dissolved into formless shapes and blinding light, he became even more so, capturing a fuller vision of nineteenth-century life at the outer reaches of experience.

Born into the lower classes, through his own hard-driving career Turner maintained a respect for industry and the experiences of those who build, forge, sail, and render. His sense for awe reflected the real lives of hardworking people of the kind we still see at Mystic Seaport, which you can still reach by land or by sea.

1 “J. M. W. Turner: Watercolors from Tate” opened at Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, Connecticut, on October 5, 2019, and remains on view through February 23, 2020.