James Panero in front of Paul Behnke’s "A Kind of Grail," 2013. Photo by Lily Panero.

The website Exhibitiona.com asked me to take part in its smart "Collectors Q&A." Here, I am delighted to highlight some of the artists whose work inspires my family at home. With photos by Lily Panero (and dad)! — James

EXHIBITIONa.COM

April 30, 2014

Collectors Q&A with James Panero

What was one formative moment for you as your interest in contemporary art began to grow?

In our living room, my parents had a catalogue from the 1982 Whitney retrospective of Milton Avery. I became fascinated with the painting on the cover, “Red Rock Falls” from 1947. The image was like a puzzle I could assemble in different ways: a monster, a neck, a hand, or the beak of Toucan Sam. It wasn’t just one thing. That’s an appeal of contemporary art: the question of it.

From left: Paul Behnke, “A Kind of Grail,” 2013; Julie Torres, “Paintings for Rachel Beach,” 2012; Gary Petersen, "Futuretime," 2013; Joy Garnett, “Blue,” 2012; Audra Wolowiec, "Concrete Sound (4x4)," 2011 (on desk); Rachel Beach, “Nod,” 2012 (in front of window); Mark A. Sprague, "Red Alert," 1952. Photo by Lily Panero

Tell us about your approach to collecting art.

I’m very fortunate in my job at The New Criterion. For my Gallery Chronicle column, which I’ve been writing every month for a decade, I get to document my evolving artistic interests. For the past several years, that’s taken me to the outer boroughs of New York, in particular to Bushwick, Brooklyn, where I’ve been inspired by the energy of their alternative art scenes. Here I see myself as an activist critic, drawing attention away from the market-driven precincts of Chelsea to these quieter corners. In part that means supporting artists and spaces both in words and deeds and, on my very limited budget, collecting where I can. Since I write my column for collectors, it helps to live with art as a collector myself and understand how work evolves in a private setting over time.

From left: works by Martin Bromirski, Austin Thomas, Lori Ellison, and Tom Goldenberg. Photo by Lily Panero.

You’ve written and spoken extensively on the current state of museums. In your article, “What’s a Museum?” you relate an anecdote about Kenneth Clark from Suzanne Bosman’s book The National Gallery in Wartime. During WWII, while museums were closed and evacuated, Clark valiantly began an initiative in which he displayed one work of art each month in a basement room, usually after taking suggestions from the public. Imagine a similar scenario. It’s WWIII, the apocalypse, a significant disaster. What would you display?

The interesting thing about art in crisis is that it comforts us more through a reflection of crisis rather than a distraction from it. So there’s the obvious gut-stirrers, such as “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” but that’s not quite right. Something better would be “The Gulf Stream” by Winslow Homer, a painting that shows us dignity in hopelessness.

From left: Matthew Miller, "Untitled (Self-Portrait)," 2009; Christopher Wilmarth, "Cut Outs from Breath Etching," 1982; Dee Shapiro, "Untitled (hatchmarks)," 2009; Austin Thomas, two untitled works (on table). Photo by Lily Panero.

What art books would we find on your shelves?

Modern Art by Julius Meier-Graefe; The Journal of Eugene Delacroix translated by Walter Pach; The Tradition of the New by Harold Rosenberg; Art and Culture by Clement Greenberg; The Age of the Avant-Garde by Hilton Kramer. Before bedtime, my daughter and I like to flip through Masterpieces of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

On right: Kerry Law, “E.S.B 11/21/11,” 2011. Photo by Lily Panero.

Tell us about the last exhibit you saw and found compelling.

The “Invitational Exhibition” at the American Academy of Arts and Letters. It’s the lead review in my latest Gallery Chronicle.

Would you close with a favorite quote that’s art-related or speaks to creativity?

“as he seeks the food of light, so he lives in light” —Moby Dick

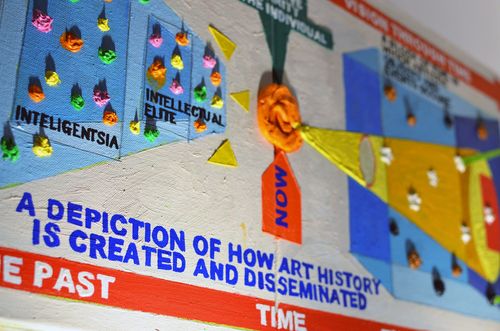

Loren Munk, "A Depiction of How Art History is Disseminated," 2010. Photo by Lily Panero.