THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

February 8, 2014

Sorry, Writers, but I'm Siding With Google's Robots

by James Panero

Copyright laws too often stifle the creativity they claim to protect. Time for a 21st-century update.

How much did mention of "copyright" increase in American books published in the second half of the 20th century? The answer is by nearly a factor of three. How about "intellectual property," a neologism designed to equate copyright with real property? By a whopping factor of 70. But what about "public domain," the term for our creative commons where the arts are replanted and renewed? The answer is almost not at all.

We know this thanks to a new program called Ngram, an offshoot of Google Books that analyzes the metadata of what is now the world's most extensive literary index. Ngram gives us a sense of how ideas have circulated over the past 200 years. And when it comes to creative freedom, the numbers don't look good.

Technology companies have emerged as the key counterweight to the lawyers and lobbyists of the content giants. And that's one reason November's victory for Google Books in Authors Guild v. Google is important.

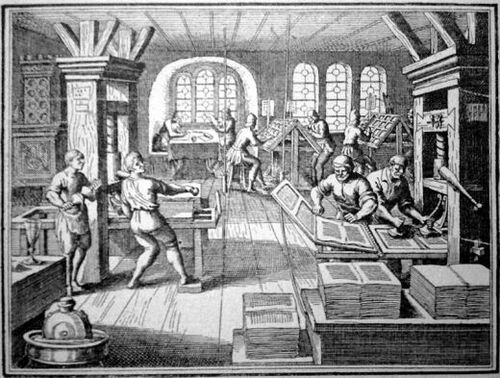

In 2004, Google announced a partnership with Harvard, Stanford, Oxford, the University of Michigan and the New York Public Library to begin scanning their holdings, turning the printed pages of millions of books into digital grist for its search mill. The robot scanners ran their eyes over everything, from books in the public domain to copyrighted material, which under current law includes most of what's been published since 1923. The results have been a boon to the culture of ideas.

Yet since Google never tracked down the millions of rights-holders of more recent works, the initiative has been embroiled in litigation over copyright infringement since its inception—even though Google has used copyrighted books only for its search index (as opposed to showing the full text). The Authors Guild, one of the plaintiffs against Google, declared the scanning "exploitation" and a "hazard for every author." U.S. Circuit Judge Denny Chin in Manhattan disagreed and dismissed the group's claims after eight years of litigation, declaring Google's project a "transformative" fair use. The Authors Guild has vowed to appeal.

As a writer, I'm siding with the robots. Google Books is far from perfect: Even advocates have worried about the consolidation of scanned information, fearing it will lead to a new digital monopoly. But it brings literature into the online world, exposing a younger generation to books they otherwise would never encounter.

Google Books' legal victory can also be seen as a chink in the armor of ironclad copyright laws. Copyright was never meant to be an indefinite "intellectual property." Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power "To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries." Much like patents, copyright was a utilitarian measure to protect creative work through a temporary government-granted monopoly.

For the founders, that meant a protective period of 14 years with the right of renewal for another 14. Since then, and especially over the last three decades, the terms have exploded. For self-made work, copyright is now in effect for the life of the author plus 70 years. For work-for-hire, the terms are 95 years after publication or 120 years after creation, whichever is shorter.

In Congress, the terms have tended to have the curious ability to grow just as Mickey Mouse is set to exit copyright, effectively locking down America's cultural patrimony to protect Disney. The "Copyright Term Extension Act" of 1998 is commonly derided as "The Mickey Mouse Protection Act," since it extended Disney's control of the cartoon character for another 20 years. The motion picture industry has argued for even more—a perpetual copyright, or "forever less one day." But would this actually be good for the arts? Numerous studies, such as a 2007 analysis by economist Rufus Pollock at Cambridge, have shown that far shorter terms would maximize creative output.

Considering the Democratic Party's ties to Hollywood, Republicans should be the natural leaders on intellectual property reform. Conservatives such as Reihan Salam, Patrick Ruffini, Timothy P. Carney and Jordan Bloom have argued convincingly for it—but so far the party isn't listening. When Derek Khanna, a young policy analyst, wrote a white paper in 2012 for the Republican Study Committee on rolling back copyright, he was shown the door. "The Republican Party hasn't been pro-innovation," he explained to me. "Copyright reform is a vital component of a more forward-leading platform."

At the start of 2014, Duke Law School's Center for the Study of the Public Domain published a list of books that would be entering the public domain under the laws that existed through 1978. For works ranging from Jack Kerouac's "On the Road" to Dr. Seuss's "Cat in the Hat," "you would be free to translate these books into other languages, create Braille or audio versions for visually impaired readers . . . or adapt them for film." Too bad: Under current law, you can't.

"Poetry can only be made out of other poems; novels out of other novels," wrote the critic Northrop Frye. "Literature shapes itself, and is not shaped externally." The freedom to work with a renewed public domain should be our inheritance—if only we stopped Mickey Mousing around with copyright.