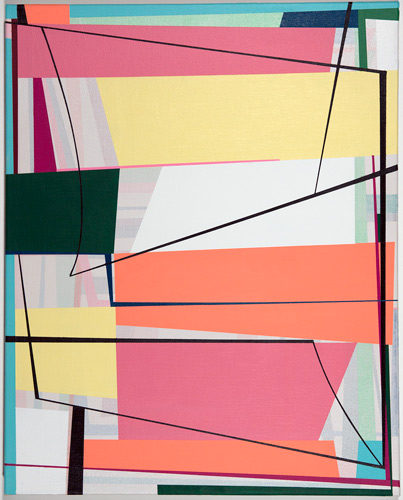

Gary Petersen, Far Away (2014), acrylic on canvas, 20 x 16 inches, Theodore:Art.

THE NEW CRITERION

February 2015

Gallery Chronicle

by James Panero

On “Gary Petersen: Not Now, But Maybe Later” at Theodore:Art, “Philip Taaffe” at Luhring Augustine, “Through the Valley: New Paintings by Devin Powers” at Lesley Heller Workspace, “Fran O’Neill: Painting Her Way Home” at Life on Mars, “Sideshow Nation III: Circle the Wagons” at Sideshow Gallery, and “Paperazzi IV” at Janet Kurnatowski Gallery.

Geometric abstraction is painting at full volume, electrified, supremicized. It’s a manufactured nature, an artificial light, a polished gemstone. It can also be overwrought, and not for everyone, but it’s rarely dull, even if we have come to recognize its terrain of colorful shapes and sharp angles. That modern painting has long employed geometry for its own ends hasn’t taken the dazzle out of these forms. On the contrary, as artists have tapped geometry’s kaleidoscopic potential, the mode has been energized by refracting its own history. Kazimir Malevich could describe his “ascent to the heights of nonobjective art” as a pioneer, watching as “the familiar recedes ever further and further into the background.” Contemporary geometrists can take their inspiration from beside and behind them just as much as they can from far out front.

Writing about “What Abstract Art Achieved” for the New York Times Magazine in 1985, Hilton Kramer observed that, “By rigorously eliminating any trace of a recognizable subject matter in art and giving a radical priority to the most impersonal aspects of pictorial form, the creators of geometric abstraction have redefined the nature of esthetic experience.” As a result of this redefinition, “On the design of everything from the built urban environment to the most mundane objects of commercial and household use, forms deriving from the vocabulary of geometric abstraction have had a powerful and unremitting impact. The contemporary scene is literally unimaginable in isolation from its pervasive influence.”

Today’s geometric painting can therefore be both a vision of Malevich’s pure feeling and a reflection of some form of nostalgia for that sensation. At its best it might be a combination of the two and more. Now with a solo show at Theodore:Art in Bushwick, Gary Petersen mixes the geometries of classical modernism with space-age memories and feel-good color.1

In the days before his opening, Petersen created two site-specific wall paintings, floor to ceiling, that bracketed the view looking into the gallery and served as highway invitations to the show. Painted with a background of bubble-gum-pink acrylic, they each employ forms that will be familiar to those who have followed Petersen through his many recent group exhibitions: tapered lines leading to rectangular vortexes of color. The forms are hard edge, but the colors are cream puff. The baby blues, lime greens, and grape purples have a Drive-Thru palette, while the shapes are TV hypnotic—Josef Albers by way of “Laugh-In.” They are rigorous and fun, lively and controlled, and advertisements for the latest models of smaller Petersens hanging on the showroom walls.

These smaller works on canvas, all from 2014, all of which could fit under your arm, reveal Petersen’s technical control over his sharp angular forms along with his willingness to give them room to develop and transform one to the next. Ovals, triangles, arcs, and rectangles assemble and rest over a secondary scrim of background shapes. The compositions are Piet Mondrian and Fritz Glarner mixed with Eames-era optimism. They give off a sense that our best times are still ahead of us, or at least we remember a time when they still were.

Just a block away at Luhring Augustine’s cavernous Bushwick outlet is Philip Taaffe, a painter who made his name as a pioneer of “Neo Geo,” a 1980s term for a “new geometry” that filtered geometric forms through pop sensibilities.2

To me, Taaffe’s paintings convey more geometric awe than pop irony, even as they employ some cool seriality and sly encoding. At Luhring Augustine, what’s first striking about them is their size and skill. Taaffe uses every possible process imaginable to stamp, stencil, marble, collage, and silkscreen his canvases with colorful symbols that look beyond the recent abstract canon to draw on a worldwide history of geometric form. The work serves as reminder that geometry has been a foundation of all art, from primitive hieroglyphics to single-point perspective, long before modernists like Malevich rediscovered it.

Taaffe seems particularly interested in mining totemic shapes and alchemical images, with each canvas seeming to coalesce around a different set of cultural and historical touchstones, whether it be architectural ornamentation, Renaissance tilework, or fountain design. His largest canvas, Glyphic Field (2014), over nine feet tall and twenty feet wide, is also his most captivating. Its debt to Matisse’s cut-outs is unmistakable. Yet rather than fish up the forms of the Mediterranean, Taaffe excavates the glyph carvings of prehistory. His painterly effects remove them from the dusty past and seem to reanimate them with a certain glowing power. As a reward for close viewing, there are even a few extra surprises that come to the surface of the glyph soup. A modern clip-art image of an eagle? Taaffe isn’t saying what it means. Yet as with all of his forms, we feel it must mean something.

Devin Powers, Woden (2014), oil on carved wood, 30 x 24 inches, Lesley Heller Workspace.

"Breakthrough” might be an overused word, but at Lesley Heller Workspace on the Lower East Side the painter Devin Powers has done just that.3

For his second solo show at the gallery, Powers takes the sharp facets of his geometric compositions, previously rendered in oil and ink for his first exhibition at the gallery, and carves them in wood, creating wild abstract reliefs that sometimes break and burn right through the picture plane. The evolution feels experimental, but also essential when perceived against the topography of his flat designs, where you just want to dig in. Powers is driven by an intuition that quite literally cuts against the mathematical programs of his compositions.

His works rests on the point between control and expression. The precision of his crystalline form is balanced against the rough feel of the carved wood, which he tools by hand. Sometimes his facets get carved out, while other times he leaves them painted and flat. Symmetries and programs work against the free forms and sparkling colors of these reliefs as they break out of the square frame, spiraling out across the wall with an internal energy fed by a crystalline imagination.

At times this energy can be too much—too big, too busy, too much flashing color—as the spiraling patterns get away from us. Best are the examples that settle into some final resolution, such as the muted crystals of Cathedral(2014). Powers may sense this too. My favorite work here is, from what I understand, also his most recent. In Woden (2014), warm taffy twists of color and shape cool into a squared-off whole. It’s a perfect confection that finishes off one exhibition and tempts us for the next.

Fran O'Neill, g's sunset (2014), 84” x 84”, oil on canvas, Life on Mars.

At the opening for the painter Fran O’Neill at Life on Mars, another gallery, like Theodore:Art, along the always-rewarding main drag of Bushwick’s 56 Bogart building, I found myself puzzling over an important question with the artist Dee Shapiro and anyone else who would listen in.4

How does she do it? What I meant was, how does Fran O’Neill achieve what I consider to be her signature sweep of color across canvases over six feet square? A sponge? Some kind of squeegee? We had our theories, but none of them seemed quite right, and indeed they weren’t. The textures of her line, especially where they skip a beat, are somehow too natural, too “shimmery” (to take a title from her best work), for any of those tools.

The answer came when the artist arrived and I asked her myself. She pointed to the underside of her arm. After a few moments of mental processing, the gracefulness of O’Neill’s paint handling made much more sense to me. For her big strokes, O’Neill uses nothing more than herself to push oils across canvas. It’s a uniquely physical process, one sized to the canvas and her own frame, and results in something I now see, in part, as a set of movements captured in one long exposure. This is not at all to suggest her work is merely the result of some actionist happening. Her paintings are nothing like Yves Klein’s raunchy “human paintbrush” performances, which would today certainly land him in the court of microaggressions.

A native of Wangaratta, Australia, O’Neill started off as a landscape painter. The turbulent thunderstorms of her former home are never far from her work, helping to explain the title of this exhibition and also her increasingly gestural paint handling, as she finds a way to tap her own physical atmospherics. Sometimes these movements can get messy. Perhaps that’s the idea behind Meeting You, a two-paneled work joined as one from 2014. Best are the works that sweep the mess away with one final flourish.

Installation view at “Sideshow Nation III: Circle the Wagons,” Sideshow Gallery. Photo: Vincent Romaniello.

If you could see just one painting show this year, the annual group exhibition at Richard Timperio’s Sideshow Gallery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn should be top of your list.5

I have written about this increasingly adventurous annual blowout just about every year. Yet with over six hundred artists represented from floor to ceiling and in every space in between, the exhibition is a one-stop shop—or a final stand, given the title—for what’s happening now, casting an ever wider net over the greatness of the borough and beyond (um, hello, Brooklyn Museum). This year, in what is a natural synergy, some younger Bushwick painters are mixed in with the older generation of studio artists who came of age in Soho in the Sixties and Seventies and beyond, including some surprisingly big names for an outer borough show.

Installation view of “Paperazzi IV,” Janet Kurnatowski Gallery. Photo: Vincent Romaniello.

Concurrently, on a smaller scale, and with many of the same names, is the return of “Paperazzi” at Janet Kurnatowski Gallery in nearby Greenpoint—the equivalent omnium gatherum for works on paper.6 With most of the works now directly pinned to the walls rather than spreading out in matted frames, the evenness of this exhibition has never been greater. Taken together, the efforts of these two small independent galleries have accomplished more than any museum department or curatorial committee has done in showing us the energy of the artist’s studio today.

1 “Gary Petersen: Not Now, But Maybe Later” opened at Theodore:Art, Brooklyn on January 10 and remains on view through February 22, 2015.

2 “Philip Taaffe” opened at Luhring Augustine, Brooklyn, on January 17 and remains on view through April 26, 2015.

3 “Through the Valley: New Paintings by Devin Powers” opened at Lesley Heller Workspace, New York on December 14 and remains on view through February 1, 2015.

4 “Fran O’Neill: Painting Her Way Home” opened at Life on Mars, Brooklyn on January 16 and remains on view through February 15, 2015.

5 “Sideshow Nation III: Circle the Wagons” opened at Sideshow Gallery, Brooklyn on January 10 and remains on view through March 15, 2015.

6 “Paperazzi IV” opened at Janet Kurnatowski Gallery, Brooklyn on January 16 and remains on view through February 15, 2015.