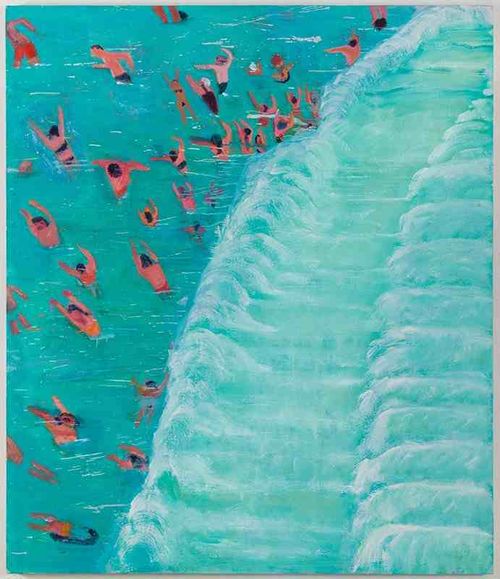

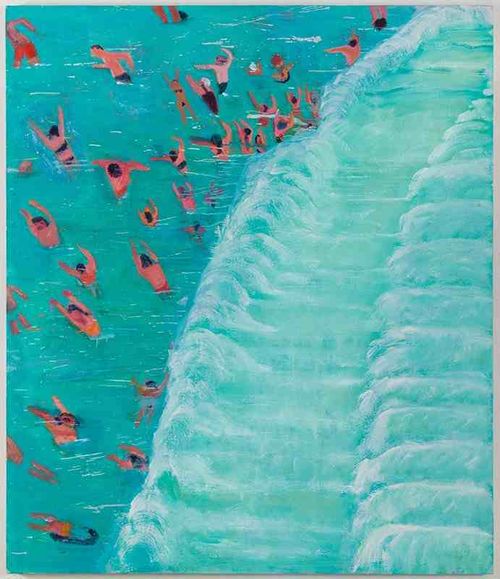

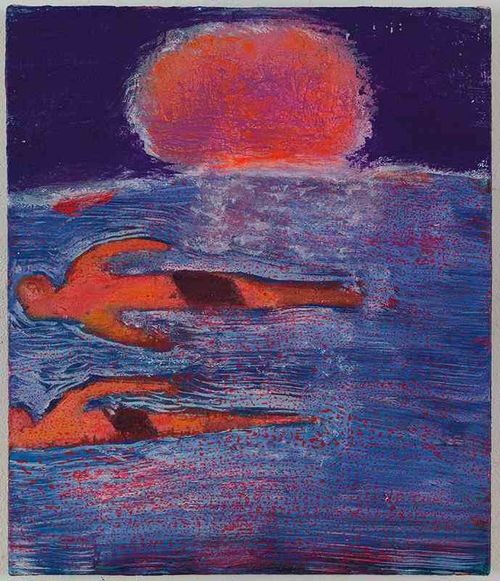

Katherine Bradford, Fear of Waves (2015), Oil on canvas.

THE NEW CRITERION

February 2016

Gallery Chronicle

by James Panero

On “Katherine Bradford: Fear of Waves” & "Elisabeth Kley: Ozymandias" at Canada; “Carolanna Parlato: A Delicate Balance” at Elizabeth Harris Gallery; “Ronnie Landfield: Five Decades” at Stux + Haller; & “Lori Ellison” at McKenzie Fine Art.

Over the last few years, the haunting work of Katherine Bradford has been hard to miss. Her small paintings have popped up in dozens of group exhibitions. Roughly painted images of ships or supermen or space aliens: the iconography may shift, but the mood conveyed is unmistakably her own. Her paintings might be new works, but they feel like old souls, like rediscovered artifacts or shop signs. In their studied distress, her paintings recall the wear that Elie Nadelman might rub into his sculptures, or Albert Pinkham Ryder bake into his ships—objects once tightly held but now forgotten. Bradford’s primitivist paint handling reflects her lost subject matter, fragments of fuller, once glamorous stories that have now been effaced, or even submerged.

The specter of water has been a recurring theme for Bradford, a longtime fixture of New York’s alternative art scene, both in her paintings of ghostly ocean liners and in her faceless divers, traveling down in the opposite direction of her rising supermen. In Bradford’s subtle hand, water has a reactive, mystical, ultimately ominous quality, refracting shapes, oxidizing colors, and overwhelming her subject matter.

Now on view at Canada gallery on the Lower East Side, Bradford has reached a high-water mark with large, ambitious canvases that heighten the mood and raise the anxiety around, as the exhibition puts it, a “fear of waves.”

In his 1950 book The Enchafèd Flood: or, The Romantic Iconography of the Sea, W. H. Auden writes that “the sea, in fact, is that state of barbaric vagueness and disorder out of which civilization has emerged and into which, unless saved by the effort of gods and men, it is always liable to relapse.” In the modern age, water is sold as a luxury: deluxe ocean passages, summer days at the beach, oceanfront vistas, dips in the pool. But reality still cuts against these leisurely ideals. Floods, sinkings, and drownings pull us under. The dread of disaster is never fully washed away from our primitive consciousness, or our modern view.

Bradford takes the images of water-bound recreation—swimming, diving, playing in the waves—and subsumes them in a mood of uncertainty and peril. In Fear of Waves (2015), one of the larger paintings here and the one that gives its title to the exhibition, a crowd of beachgoers observed far off from an elevated perspective, like the view from a bluff, assembles waist-deep in a pool of light blue. A set of white waves rolls towards them from the right side of the canvas. At first they appear to be relaxing in the surf. On closer inspection, they are revealed to be attempting to swim away from deep water, reaching for an unseen shore as their lips scream out in terror.

A similar sensation comes across in Surfer (2015) and Surf Party (2015). The bottom half of each painting shows figures in the water at play. But the top half conveys something else: the rising spray of an oversized wave, the potential for disaster. The outcome is a mystery. A halo of color predominates each canvas, erasing and blinding us to the particular emotions of the distant figures.

This feeling for the unknown has only increased as Bradford has located her scenes in increasingly ethereal settings. Bradford has long worked through the iconography of cosmic kitsch, with comic-book UFOs, planets, and stars appearing in her work. In her most recent paintings, some of them dated 2016 and seemingly still wet from the studio, Bradford elevates her water-bound figures into the astral plane. These settings make literal Auden’s understanding of the sea as the “symbol for the primordial undifferentiated flux, the substance which became created nature only by having form imposed upon or wedded to it.” Oversized galaxies appear in the black sky ofFloaters (2015). In Swim Team Miami (2015), divers prepare to jump from orbiting planets. Swim Team Outer Space (2015) floats on the curving surface of a purple planet illuminated by a glowing moon. While in Fathers(2016), the largest and most fraught canvas in the exhibition, nude figures face each other around the edge of a circular pool, which itself floats in a starry void.

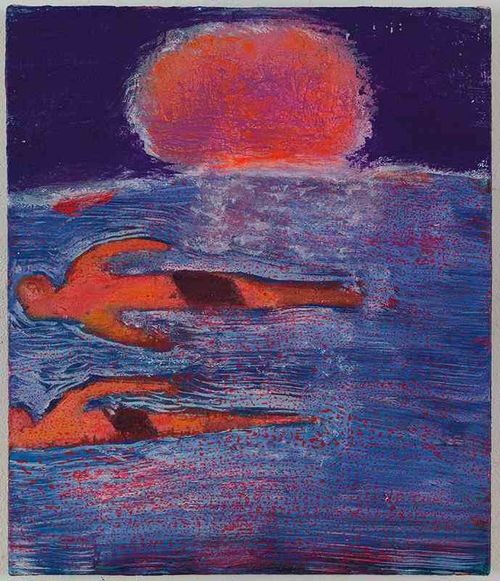

Katherine Bradford, Couples Swim (2015), Acrylic on canvas.

With her sense for mood, Bradford comes across as a latter-day Symbolist. The smaller painting Couples Swim (2015), a favorite of mine that features two figures floating under a midnight sun, recalls nothing less than the work of the Symbolist Edvard Munch. In Symbolism, his 1979 study, Robert Goldwater observed how Munch put “the meaning of his pictures into design and colour, and into the stance and gesture of the whole human body, whose pose and contour flowed and fused with a larger composition that gave direct expression to the mood and substance of the theme.” Bradford shows a similar sensibility, and a similar fearlessness around fearful sentiment.

Elisabeth Kley, installation view at Canada.

Meanwhile, in Canada’s second gallery, Elisabeth Kley presents striking black-and-white ceramics that appear pulled up from an unknown deep. Working with “homemade underglazes, with wax resist and sgraffito,” Kley impresses rough designs of unknown ethnographic origin onto her hand-made vessels of flasks and lobed bottles. Abstract trees, crosses, seraphim, eyes, tulips, leaves, axes, and flags decorate these objects in matte black-and-white, and, on the reverse, white-on-black. Prints and wall-painting round out the monochrome space, contrasting with Bradford’s colors next door, with the earthenware objects arranged symmetrically on pedestals in museum formation. In the art world, we are in a ceramic moment. Kley’s clay looks to the future by unearthing the forgotten past.

Carolanna Parlato, a delicate balance (2015), Acrylic and molding paste on canvas, 64 x 84”.

Carolanna Parlato knows how to move paint around a canvas. Five years ago, she was pouring acrylic, tipping her stretchers, and allowing her pigments to spread across her canvases, reacting with her medium. Her self-made technique created remarkably accomplished compositions. So I was surprised to see her move beyond this mode into what might be considered more traditional paint handling. But seeing Parlato’s latest exhibition at Elizabeth Harris Gallery, I am glad she did.

The first sensation I experienced entering “A Delicate Balance” is the smell of paint. I might even say it was the smell of white paint, but that could be the scent of the gallery wall reacting with my perception of this latest work. Parlato now layers splotches of color on white canvas. Her shapes resemble paint tests, the way you might spread out a fresh coat on a white wall. But just like her poured canvases, these shapes congregate not as random marks but rather as well-assembled compositions.

Here “balance” is achieved not just among her colors but even more significantly with her use of white. I have long felt that primed white canvas rarely works when left as unfinished surface in painted compositions. Unlike works on paper, where unfinished white ground forms a transparent and even illuminating surface, bare primed canvas has an invasive presence that usually requires further treatment. Parlato senses this as well. Her latest work is most importantly white-balanced, with scrims of white overlaying both her color blocks and her white ground.

Parlato’s use of thin acrylics is especially well suited for such subtle layering, as the squares and squiggles of a delicate balance (2015) seem to dissolve into her background—an effect I find more convincing than in the smallerBurst (2015), where her colors sit more on the surface. Meanwhile Clouded Memory is another show-stopper, with a more forward composition of red, purple, orange, and yellow surrounding earth tones of greens, browns, and blues. This composition contrasts her shapes, not between figure and ground, but center and frame, as a thin rim of bolder colors compresses subtler shades in, again, a delicate and accomplished balance.

Ronnie Landfield, Installation view at Stux + Haller.

Ronnie Landfield was one of the young painters of the 1960s Soho scene who looked into the emptiness of minimalism and found his own light beyond the darkness of the void. “I realized that [Donald] Judd and his minimalist philosophy was wrong,” Landfield explains in an illuminating interview with Daniella Hansen and Stefan Stux accompanying his current retrospective at Stux + Haller. “What he was doing was representing the essence of the void, but that’s just the beginning—it’s just the doorway.”

So Landfield looked deep and began to find landscapes in his designs, part traditional watercolor, part colorfield stain, enlarged to loft-size proportions. It might be hard today to imagine the alarm that Landfield’s illusionistic turn once posed to the supposed direction of modern art. Not only was he abandoning flat abstraction for deep space. He was also drawing his real vision from fictive imagination. Neither a realist not an abstractionist, he was an impure in-between.

With work assembled over five decades, this latest exhibition demonstrates Landfield’s consistency of vision along with his evolution and revisiting of techniques. Landfield’s imagined landscapes have a childlike appeal: colorful, hill-like shapes settle into lakes and dappled valleys beneath a rain-soaked sky. Water feels like a constant presence as his colors mix and bleed into the warp and weft of his canvases, a reflection of his water-based acrylic medium.

The ease of Landfield’s paint handling is masterful. If anything, his likeable visions come too easily. As a nod to his minimalist beginnings, at times Landfield introduced more hard-edged elements into these soft designs. Especially in the early work, I can understand their origin: his color bars form a minimalist frame, the reminders of a more concrete present from which to enter his maximal vision.

In his interview, Landfield reveals that Clement Greenberg disagreed with the imposition of these blocky forms, saying he should paint one way or the other, not both. Clem had a point: these impositions still seem like half steps. Landfield is at his best when he allows our full immersion into his lush found space, from the early Blue Wall (1970) to the more recent The Wind and the Rain (2012)—a drenched composition with colors to touch and space to breathe.

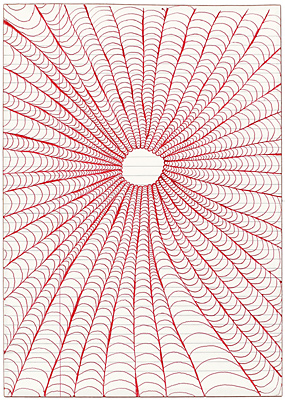

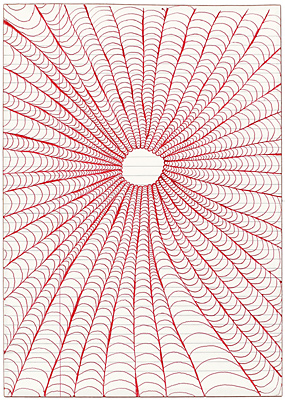

Lori Ellison, Untitled (2014-15), Ink on notebook paper, 11 5/8 x 8 1/4 inches.

A final word about the artist Lori Ellison, a quiet person of outspoken conscience who died last August after a battle with cancer and years of health challenges. Ellison appeared in this column many times. Her obsessive work deployed seemingly simple patterns on provisional materials—often lined notepad paper and ballpoint pens—to dazzling effect. In an age that expects its art to be big, she worked notably small, inviting us into her private world while drawing connections among the artists of the Lower East Side and the outer-borough art scenes. Reflecting her captivating work, she was also an absorbing presence on social media, part aphorist, part provocateur, who wore her heart on her virtual sleeve. “Some ideas are responsible for the people who believe in them,” she posted online in the weeks before her death.

We are fortunate that Ellison could dedicate her energies to the planning of her final exhibition of new work, which went on view this past December and January at McKenzie Fine Art. One new chromatic series she developed of gouache on small wood panels took its inspiration from the undersea cutouts of Matisse. But it was her work on paper that, to me, remained her strongest, with intimate thoughts drawn out to their ultimate conclusions.