THE NEW CRITERION, March 2017

On “Icons of Modern Art: The Shchukin Collection” at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris.

The Russian Revolution twice robbed Sergei Shchukin. The first theft was Lenin’s “nationalization” in 1918 of his collection of modern art, among the greatest of the twentieth century—and, for a flash, the eastern conduit, along with the collection of Ivan Morozov, of the latest advances in French painting. The second theft was the loss of Shchukin the man, and the legacy of his singular eye, as his collection was ingested and consumed by the Soviet State, only to be regurgitated in the thaw as another lost Russian treasure.

Christian Cornelius (Xan) Krohn, portrait of Serguei Shchukin, 1916. Oil on canvas, 191 × 88 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

But Shchukin the man was indeed a figure at the center of modern French painting in the early twentieth century. If he was not at the core of the Parisian avant-garde like his associates the Steins, from whom he purchased work (at discount), Shchukin was at least the equal if not the better of Albert Barnes, perhaps his closest American industrialist analogue and, like him, an essential patron of Henri Matisse.

“It was the art of the Paris avant-garde that dominated the thinking of the Russian modernists in their accelerating quest for the absolute,” wrote Hilton Kramer in these pages in “Abstraction & utopia” in September 1997.

Crucial to this development were the great collections of the modernist School of Paris that had been amassed by two remarkable Russian businessmen, Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov. With their immense holdings in the most advanced painting of the Paris school—especially the works of Matisse and Picasso—these collections played a central role in acquainting the artists of the burgeoning Russian avant-garde with splendid examples of the new Fauvist and Cubist art long before such objects were exhibited in significant numbers in the museums of the Western world.

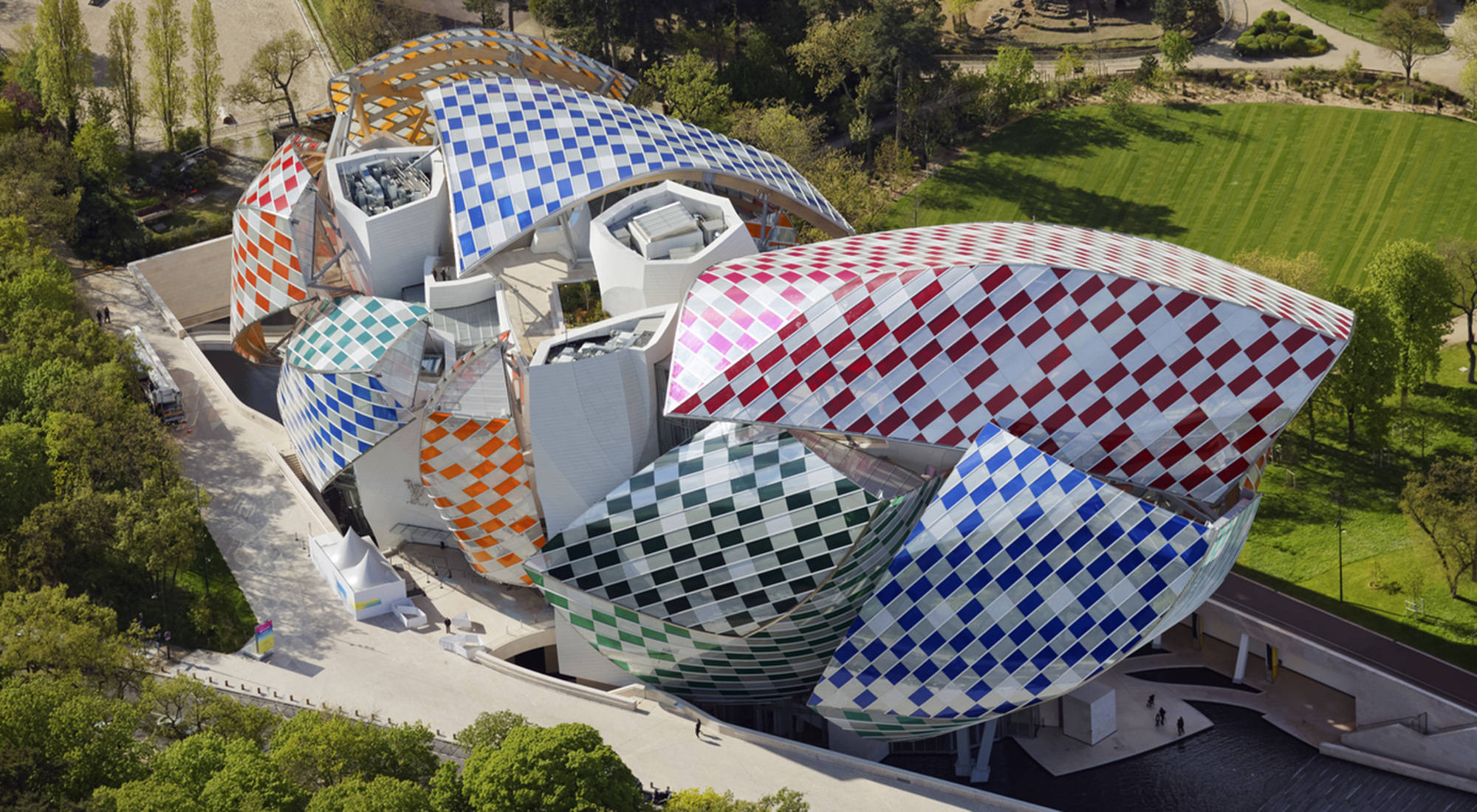

Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris

I wish Hilton could see Sergei Ivanovich finally reanimated in a remarkable show, the definition of a “must-see exhibition” called “Icons of Modern Art: The Shchukin Collection” that will be completing its run in Paris on March 5.1

I doubt Hilton would have cared for its venue, although I am certain it would have been occasion for much comment: not the Louvre or the Musée d’Orsay, but a new Parisian institution, the Fondation Louis Vuitton. Inaugurated in a rather inaccessible corner of the Bois de Boulogne in 2014, this grand folly designed by Frank Gehry serves as a spectacular monument to its patron, Bernard Arnault, the chairman of lvmh and the president of its Fondation. The seemingly elevated institution, requiring timed tickets to get past its faceless security gates, floats above a rushing fountain and billows (temporarily) in the checkered tapestry of the colors of the commedia dell’arte. Visible like a balloon from the observation deck of the Eiffel Tower, the museum has become something of an arc of culture in a terrorized city lately defined by liberté, égalité, sécurité—the plan Vigipirate (“vigilance and protection of installations against the risk of terrorist bombings”) now a constant presence.

Ultimately the Fondation Louis Vuitton speaks to the international sway of a new elite that finds its model in the patronage of the Gilded Age, including Shchukin himself, which may not offer such a bad example to follow. One-hundred-twenty-seven works by Monet, Cézanne, Gauguin, Rousseau, Derain, Picasso, and most notably Matisse, among others, with many of them never having returned to Paris since the moments they were painted: I doubt any public institution could have mustered the resources today to pull together such loans from the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg and the Pushkin State Museum in Moscow, where Shchukin’s collection was eventually divided and conquered. After all, “Russia,” Arnault writes all too tellingly in the introduction to his exhibition’s catalogue, is “a country with which, for so many years now, LVMH and its Houses have enjoyed strong relations, based on complicity and collaboration.”

“Icons of Modern Art: The Shchukin Collection” at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris.

Unlike previous exhibitions that have famously resurrected several of these paintings from the purgatory of the workers’ utopia, “Icons of Modern Art” is the first to breathe life back into the man who saw their brilliance and brought them together. “Marginalized for nearly a half century because of ideological reasons, the collection of Sergei Shchukin remains little known to the general public in the West even today,” writes Anne Baldassari, the curator of the exhibition and the editor of its catalogue. “In fact, since it was broken up in 1948 it has never been brought together as a singular and coherent artistic entity.”

Born in 1854, Shchukin was the quiet, stammering heir to a Muscovite family of textile merchants. Smart in business, he cornered the textile market during the general strike and panic of 1905 in much the same way he began pursuing French painting just seven years earlier in 1898, beginning with several Impressionist works he acquired through the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel.

The exhibition and catalogue both speculate on Shchukin’s motivations: a Russian “Old Believer” with a particular understanding of modernist iconography; a wandering soul who lost his wife, his brother, and two sons in a short and tragic span between 1905 and 1910; an industrial magnate who was born and trained to cultivate a “textile eye.” I suspect the answer was a combination of the three, fueled by his vast and increasing fortune and an instinct for speculation.

Shchukin bought all he could from Paris and imported it back to Moscow, packing the work into his home in the Trubetskoy Palace. A melancholic series of photographs of the palace rooms attests to Shchukin’s achievement as he installed floor to ceiling what have now become many of the most coveted paintings of the last century. In public spirit he opened the collection to visitors every Sunday starting in 1908.

“Icons of Modern Art” does not attempt to recreate Shchukin’s original arrangement, instead presenting about half of the corpus of Shchukin’s collection across fourteen exhibition galleries. Mixed in are thirty-one additional works by the Russian modernists, such as Malevich, Rodchenko, Larionov, and Tatlin, among several others, who were arguably first exposed to the artistic avant-garde through Shchukin. A side-by-side comparison of Shchukin’s cubist Violin by Picasso from the summer of 1912, for example, with a Violin by Nadejda Oudaltsova of 1916 demonstrates the debt these Russian artists owed both to the School of Paris and to the great collector who brought so many of the best examples to Moscow.

From his start in 1898 through the outbreak of war in 1914, Shchukin pursued French painting not only at an accelerated clip but also closer to their moment of creation. Each exhibition label lists both the year of creation and the time it entered Shchukin’s collection. Several of the early rooms are concerned with Shchukin’s Symbolist, Romantic, and Impressionist pictures, such as Charles Cottet’s haunting Stormy Evening, Passers-by (1897), Eugène Carrière’s ethereal Woman Leaning on a Table (1893), and Maurice Denis’s high-Symbolist Figures in a Spring Landscape (Sacred Grove) (1897). As he built these modernist foundations, Shchukin’s approach to French painting was broad, even encyclopedic: Le Douanier Rousseau, Pissarro, Signac, Degas, Renoir, Redon, Toulouse-Lautrec, and several outstanding paintings by Monet. Up through the woven hatch-marks of Cézanne, into the color-rich Cloisonnism of Gauguin (with amazing examples here), Shchukin finally arrived at the Fauves and his groundbreaking relationship with Henri Matisse.

Red Room (Harmony in Red) (1908) by Henri Matisse; The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

Ascending up the Fondation floors, the exhibition saves Matisse for its highest and brightest rooms. At the time of their creation around 1910, his most famous commissions, La Danse and La Musique, monumental canvases intended for the Trubetskoy staircase, tested both artist and patron as the two went back and forth over their radical composition and their presentation of nudity. “People may shout and laugh,” Shchukin finally wrote to Matisse in accepting the work, “but since I’m convinced that your path is the right one, perhaps time will be my ally and I shall claim victory in the end.” While each of these two paintings stayed in Saint Petersburg for the Paris exhibition, the works by Matisse that did travel remain astonishing: Still Life with Blue Tablecloth (1908–1909), Seville Still Life (1910–1911), The Studio (The Pink Studio) (1911), and the iconic Red Room (Harmony in Red) (1908), just to name a few, all speak to the precision of Shchukin’s “textile eye” as Matisse stitched color and shape together in stunning compositions.

Compared to the floridity of these works, Shchukin’s final push into Picasso seems almost anticlimactic, even as more examples are on display here (twenty-nine in total) than by any other artist. Yet judging by the Russian artists on view, it was Picasso’s cubist architecture, not Matisse’s fecund color, that most affected the local avant-garde, from Ivan Kliun through Lyubov Popova and Vladimir Tatlin, as the Supremacism of Kazimir Malevich arguably synthesized the two.

The “Salle Gaugin” of the original Shchukin Collection. Photo: Fondation Louis Vuitton

In the Soviet era, the dissolution of Schukin’s art was almost as swift as its creation. As Shchukin and his family fled the Bolsheviks and took up exile eventually in France, Lenin appropriated Shchukin’s collection of 274 works as having “national importance for the education of the people.” For a time the collection continued to be exhibited in the Trubetskoy Palace, now renamed The Museum of Modern Western Painting, or MNZH 1, to distinguish it from the nationalized collection of Ivan Morozov, MNZH 2. In 1928 the two collections were combined in Morozov’s mansion as the State Museum of Modern Western Art (GMNZI). Here the collection fell under the increasing scrutiny of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate for consisting of art that was socially useless and harmful to the proletariat, advancing an aesthetic formalism that was considered hostile to the state.

In 1948 Stalin finally declared the Shchukin and Morozov collections to be “composed mainly of ideologically inadequate, anti-working class, formalist works of Western bourgeois art devoid of any progressive, civilizing value for Soviet visitors.” Declaring that its presentation “to the working-class masses is politically harmful and is contributing to the spread, in Soviet art, of hostile, bourgeois, formalist opinions,” Stalin liquidated the combined collections within ten days. As the art disappeared into the storage vaults of the State Hermitage and Pushkin museums, the former home of the GMNZI, mounted a three-year “Exhibition of gifts to Comrade Stalin from the peoples of the ussr and foreign countries.” A thousand busts of Stalin replaced the great modernist works.

The descendants of Sergei Shchukin made a special bargain in lending their support to “Icons of Modern Art.” “This kind of recognition has had a profound effect on our family,” several of them write collectively in the catalogue preface, “a way of telling us and our children: never give up hope, the work will win the day.” In order to resurrect the legacy of their ancestor, they were required to drop any claims over his work for his collection to leave Russia, and so run the risk of seizure. Yet even by avenging one crime by acceding to another, these heirs have allowed for the spirit of Shchukin to finally bear witness to one of the greatest art thefts of the twentieth century, with a collection that serves as a visible symbol of the infinite injustices of the Bolshevik Revolution. While the restitution of artwork from the Nazi era still reminds us of the wickedness of race-hatred, we must continue to wait for a full reckoning of the class-hatred that was perpetuated by the Soviet regime and its enablers.

In 1936 Sergei Shchukin died in Paris at age eighty-two. In exile he became a recluse. He never bought art again. At least, for a brief moment, he lives on here through the genius of his collection.

1 “Icons of Modern Art: The Shchukin Collection” (Icônes de l’art moderne. La collection Chtchoukine) opened at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, on October 22, 2016, and remains on view through March 5, 2017.