THE NEW CRITERION, February 2022

On “Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

One of the revelations of “Inventing Abstraction,” the 2012 exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, was the extent to which painting led the modernist movement from behind. moma has historically positioned its own collection of painting and sculpture at the head of the big parade—banners high and horns blaring—but “Inventing Abstraction” suggested otherwise. The advance of modernism, it turns out, was not quite as straightforward as we once thought. By bringing together “drawings, books, sculptures, films, photographs, sound poems, atonal music, and non-narrative dance,” the 2012 exhibition made the case that many creative modes assembled for modernism’s march. This seemed to have been especially true in the abstract foment of the early decades of the twentieth century. Experiments in the applied arts, in craft, and in performance could be just as important as what was happening with oil on canvas.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889–1943) was one of those artists presented in “Inventing Abstraction.” A needlepointer, costume designer, interior decorator, dancer, puppet-maker, and more, the Swiss artist was an accessorizer at the center of modernism. Yet the centrality of her life and the ephemerality of her work did not help her posthumous reputation. Taeuber-Arp’s legacy was soon eclipsed by the dominance of painting in the post-war years—and, despite his own best efforts, the works of her husband, the artist Jean Arp, who outlived her by more than two decades.

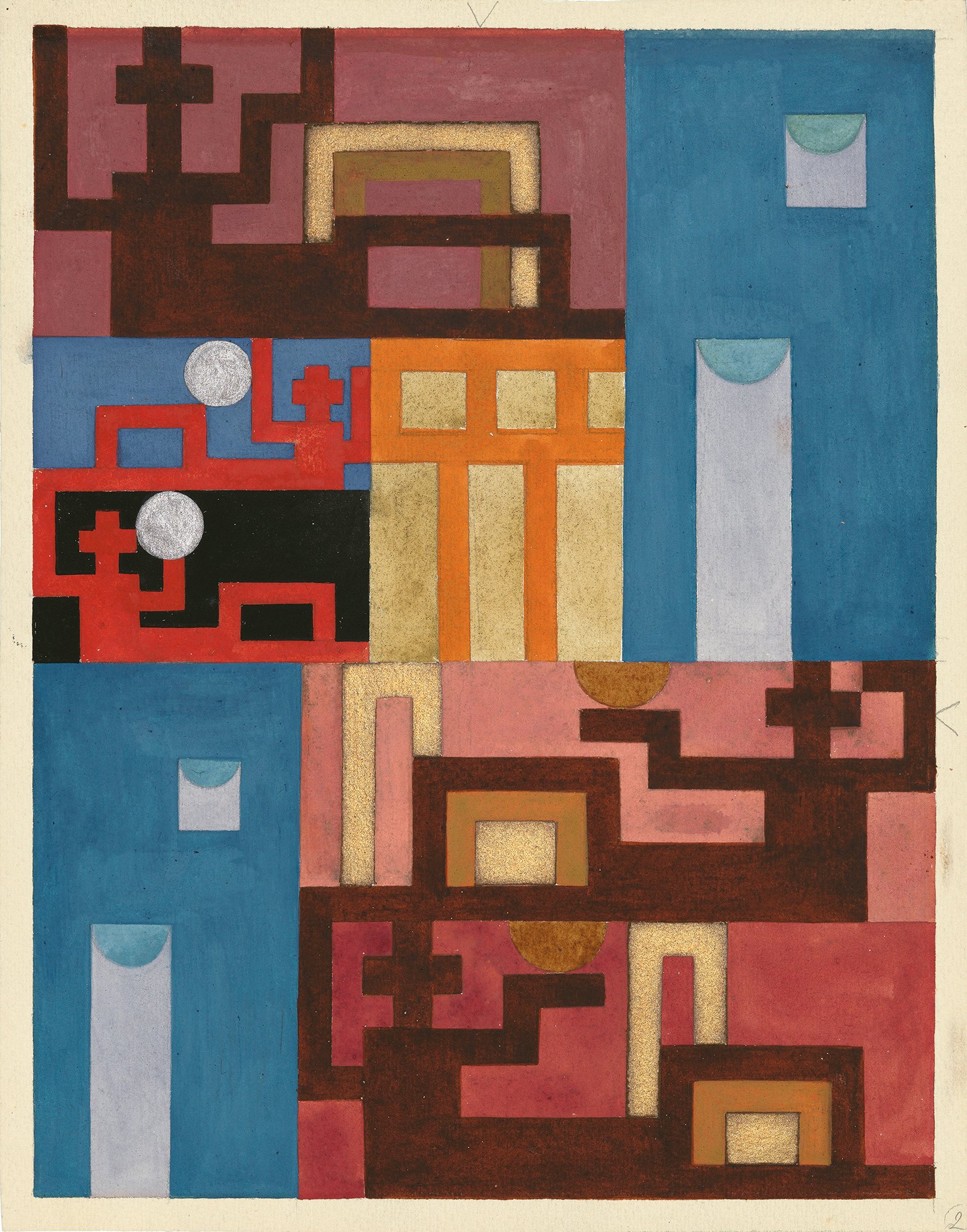

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Five Extended Figures, 1926, Gouache, metallic paint, and pencil on paper, Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin. Photo: Alex Delfanne.

“Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction,” the retrospective now on view at the Museum of Modern Art, is the type of sweeping survey meant to inspire reevaluation.1 That an overlooked woman is now up for rediscovery is a part of the pitch. With three hundred objects from over fifty lenders spread out across eight galleries, plus a three-hundred-page catalogue, the museum expects you to depart with more than a casual acquaintance with this “shape-shifting artist you probably don’t know yet,” as moma bills its show.

Taeuber-Arp was indeed wide-ranging in her artistic pursuits, especially in her heady youth, finding the common patterns in art and craft and combining them with her interests in performance, sculpture, and architecture. An early foray into embroidery provided the thread that tied her life and work together. In 1913 she graduated from Munich’s Debschitz School with a focus on textiles and the intention of pursuing furniture design. The disruption of the First World War soon brought her into the orbit of Swiss Dada—and Jean (Hans) Arp, a German from Strasbourg who had moved to Switzerland to escape conscription. The two met in 1915 and married in 1922.

Curated by Anne Umland (moma), Walburga Krupp, Eva Reifert (Tate), and Natalia Sidlina (Kunstmuseum Basel), “Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction” leaves no stitch dangling. The chronological presentation begins with the needlepoint, beadwork, wooden objects, and drawings that Taueber-Arp created in Zurich between 1915 and 1920. Influenced by the Jugendstil, along with William Morris and his belief in the transformative power of the applied arts, Taueber-Arp created textiles that were a mix of abstract patterns and abstracted symbols. “In our complicated times,” she wrote, there is a “deep and primeval urge to make the things we own more beautiful.” The orthogonal matrix of textile provided the structure, literally and figuratively, against which she composed her designs.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Cushion panel, 1916, Wool on canvas, Museum für Gestaltung, Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, Zurich, Decorative Arts Collection, Courtesy Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, ZHdK.

In a work such as Vertical-Horizontal Composition (ca. 1917), a design of wool on canvas, Taeuber-Arp used needlepoint’s rigid architecture both to embed and to disguise iconographic forms. What at first resembles nothing more than a pattern of rectangular shapes might, at varying distances, come into focus as a duck in profile. Taeuber-Arp carried such bitmapped semiotics to her necklaces and purses and other textile crafts. Among its tiles and zig-zags, a CushionPanel from 1916 might be implanted with abstracted flowers in its cross-stitching. An egg-shaped beaded bag from circa 1918 might contain an abstracted forest in addition to its contents.

Taeuber-Arp envisioned such patterns and motifs repeating across media, making furnishings, accessories, and everyday objects “more beautiful.” She also looked to unlock the animation in these abstract forms. As she took her shapes to three dimensions, she used turned and painted wood to create what she called her Dada Cup (1916), Amphora (1917), and Powder Box (ca. 1918)—cool, mysterious objects with anthropomorphic pretension.

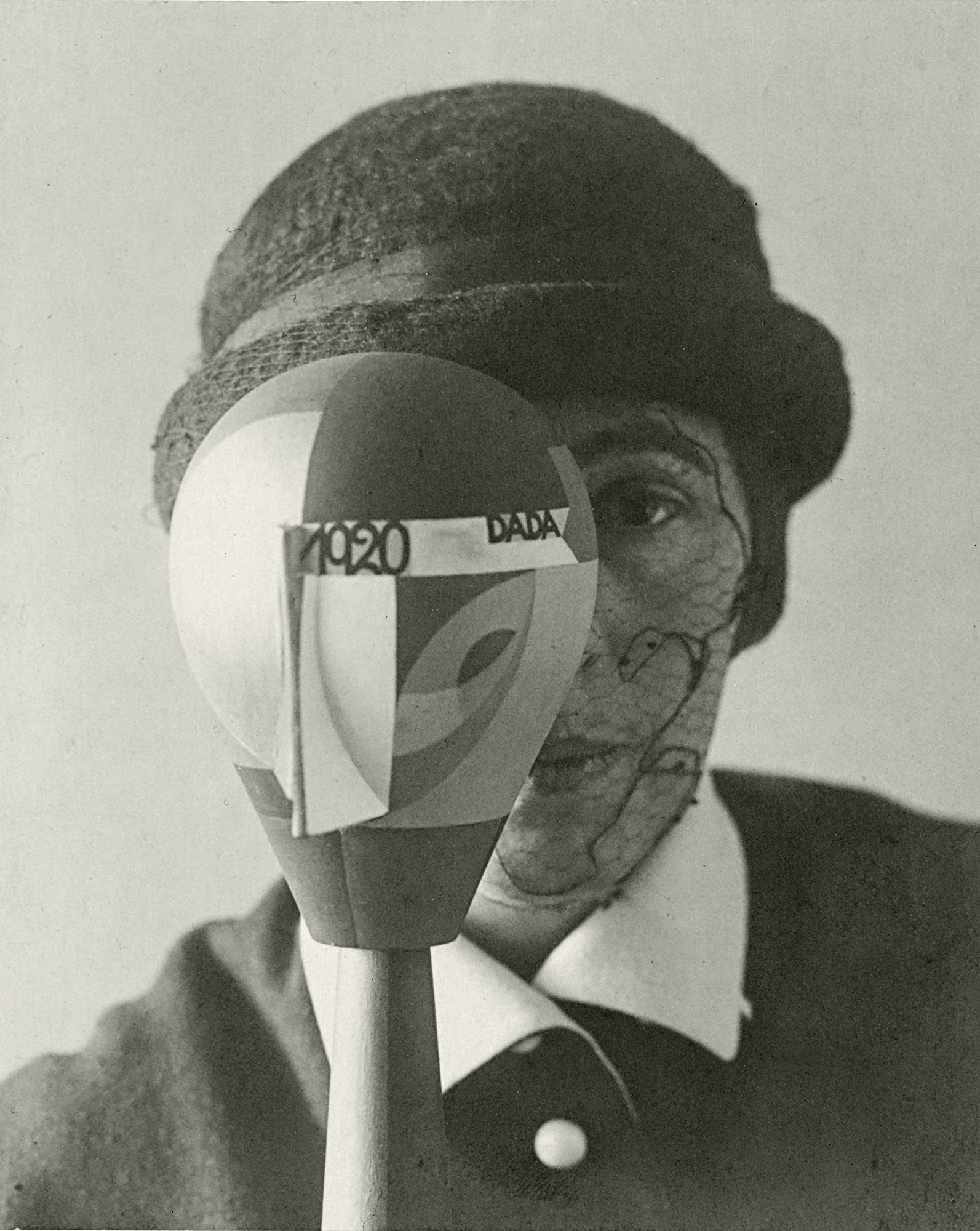

Nic Aluf, Sophie Taeuber with her Dada Head, 1920, Gelatin silver print on board, Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin. Photo: Wolfgang Morell.

You could easily miss the next room, a side gallery that is a highlight of the exhibition. Here Taeuber-Arp brought form to life through her marionettes. For a Dadaist version of the story of “King Stag,” she designed the scenery and puppets of the absurdist production. The eighteenth-century commedia dell’arte fantasy now included a Freudian subplot and a character named “Dr. Oedipus Complex.” Many of Taeuber-Arp’s scenery drawings and geometric figurines are here, along with a film of a reproduction of the performance. Also here are her photographic portraits of the same period, taken by Nic Aluf at the request of Tristan Tzara, where Taeuber-Arp looks out from behind her turned-wood “Dada heads”—the artist as modernist puppet-master, half-masked and half-revealed.

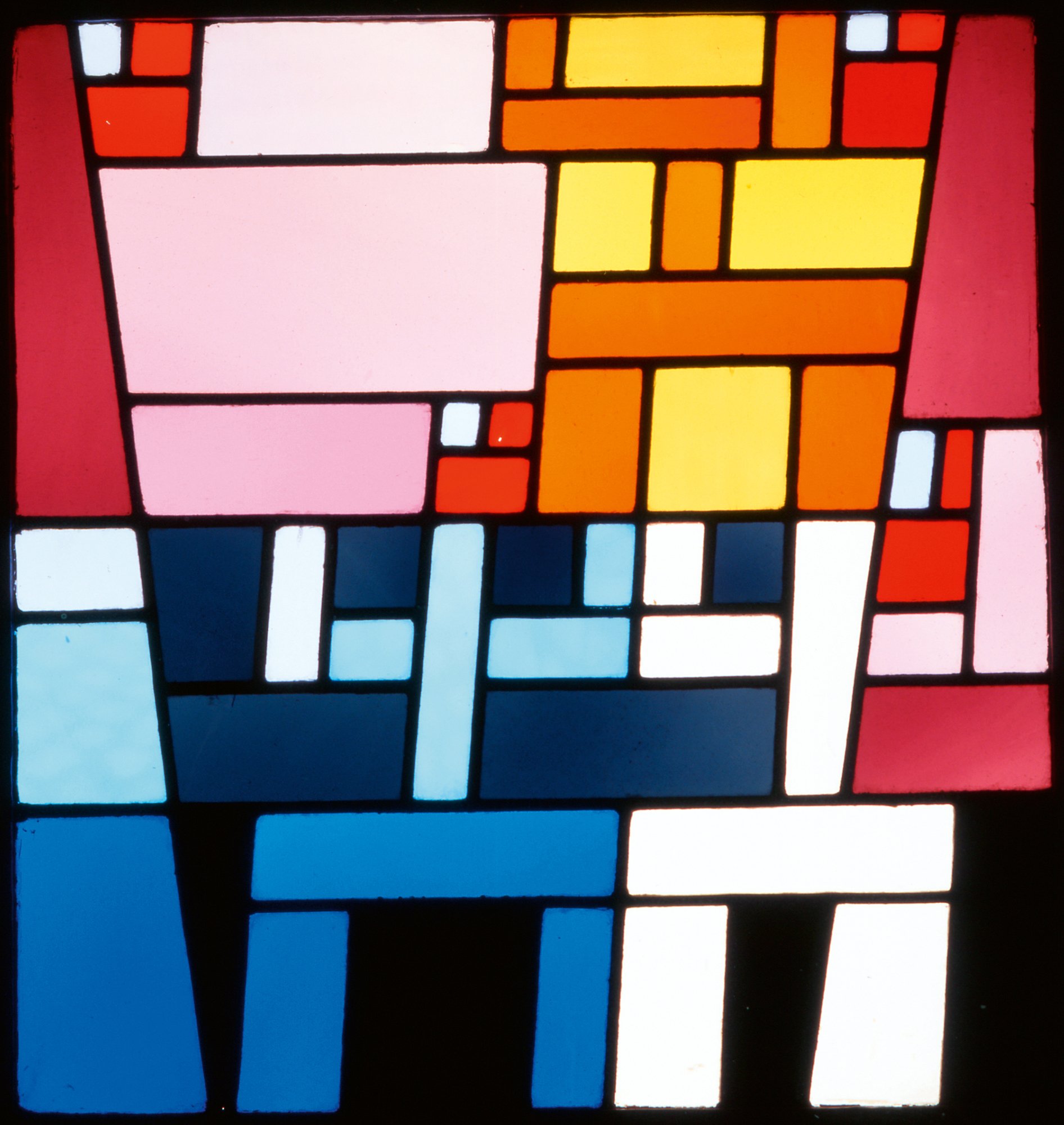

Later in the 1920s Taeuber-Arp brought her orthogonal matrices to stained glass and interior design. She imparted a sense for the “total work of art” to her floor-to-ceiling designs for the Aubette, an entertainment complex funded by the art collector André Horn and his architect brother, Paul. Taeuber-Arp covered every interior surface with textile patterns—most of them preserved now only in drawings and photographs. Inspired by the severe editing of the Bauhaus, she also looked to industrial design. She created desks for apartments in Paris and modular furniture for her own studio-house in Clamart, the town southwest of Paris where she and Jean settled in 1929 (the land was purchased in part thanks to her professional design income). All followed a similar formal logic, building up and cutting into the grid.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Off-Center Abstract Composition (stained-glass window for the apartment of André Horn, Strasbourg, France), 1928, Stained glass, Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg, France. Photo: Musées de Strasbourg.

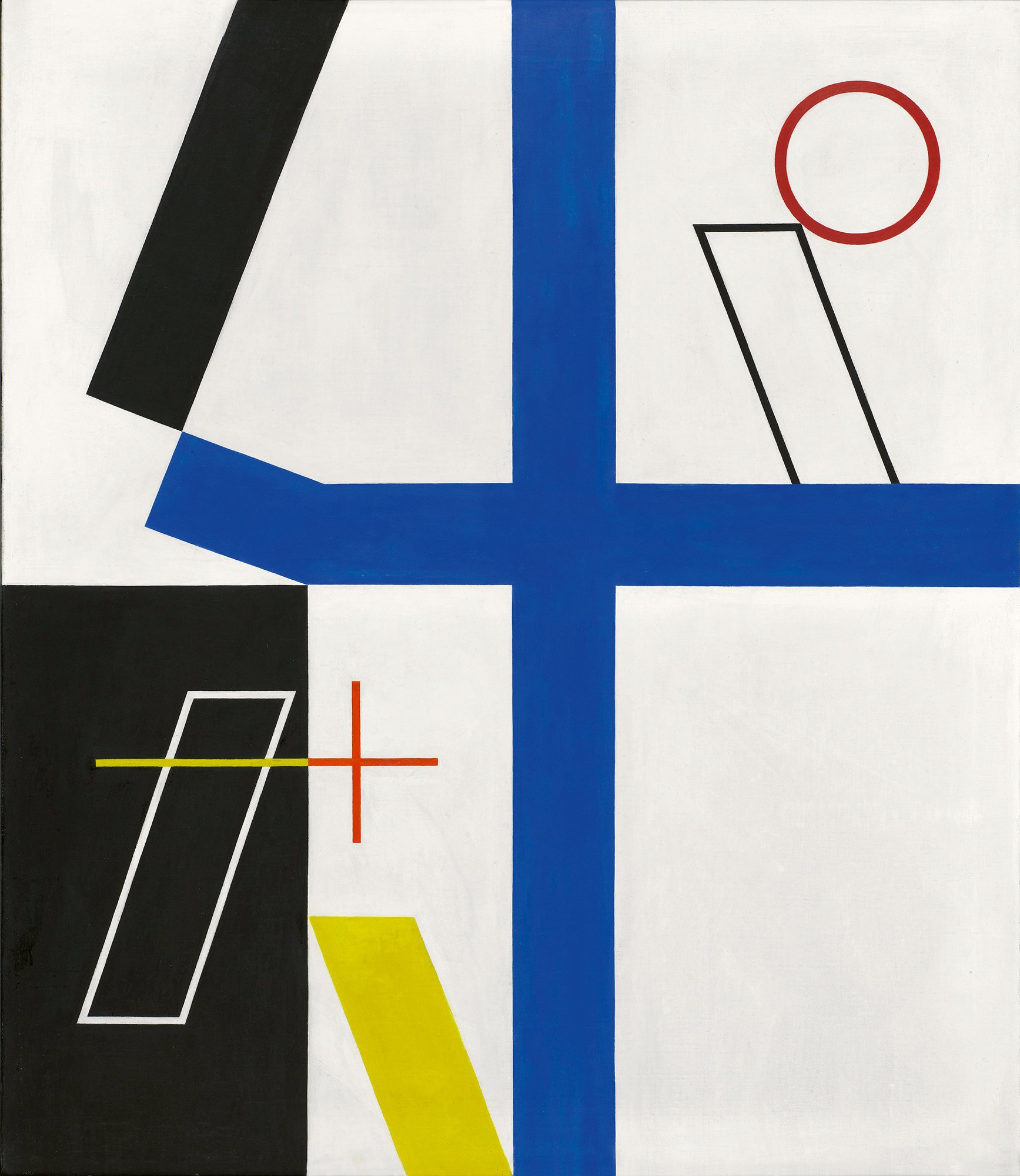

Yet Taeuber-Arp’s work never again reached the same level of abstract life as in her early experimental years from 1916–20, at the conclusion of World War I, working with Swiss Dada. As she then turned to oil on canvas in the late 1920s and into the 1930s, the geometry remained but the dynamics fell more flat. Her imbibing figures in Café (1928), with their circle heads and street-sign bodies, fail to rise above graphic design. She carried such colorform shapes through their many permutations and combinations, but the graphic experiments, treating paint like just more needlepoint, were more smoke than fire. In its division of the canvas, cut through with colorful lines, Six Spaces with Four Small Crosses (1932) reaches for a more nuanced syncopation. Still, it is no “boogie-woogie,” Broadway or otherwise.

There are many such modernist echoes throughout this exhibition: not just of Mondrian, but also of Calder and, of course, her own husband, Jean Arp. A walk through moma’s permanent collection suggests these and many more affinities that “Living Abstraction,” in attempting to elevate Taeuber-Arp, ignores rather than explores. The exhausting comprehensiveness of this singular treatment, filling as many rooms as last year’s revelatory “Cézanne Drawing,” ends up diminishing her achievements by spreading the artist too thin.

The story of the supposedly overlooked creative wife, of the artist-victim in need of our rediscovery and salvation, might make for a compelling contemporary narrative, but it does not necessarily align with actual experience. The exhibition claims that “gender discrimination” is “one of the reasons Sophie Taeuber-Arp remains far from a household name.” It laments the “difficulties faced by women of Taeuber-Arp’s generation, in particular those with well-known spouses, to be considered artists in their own right—as individuals first, rather than as partners.” It also criticizes the posthumous catalogue raisonné her husband published in 1948 as “well-intentioned” but one that “occluded the vibrant, cross-disciplinary versatility that is at the heart of her singular life’s work.”

Photographer unknown, Sophie Taeuber-Arp in costume for a housewarming party organized by artist Walter Helbig, Ascona, Switzerland, August 1925, Fondation Arp, Clamart, France. Photo: © Fondation Arp, Clamart.

And yet, in a time before gender became just another political chip, the world that this artist inhabited, especially the life she lived with her artist husband, seemed determined to encourage her. After her death, in addition to publishing her catalogue raisonné, Jean Arp helped organize, at the Kunstmuseum Bern, the first retrospective of her work. With dozens of blue-chip lenders to the present exhibition, both in Europe and America, one must wonder how overlooked Sophie Taeuber-Arp has ever really been.

Timed to this exhibition, A Life through Art, a new bilingual biography written by Taeuber-Arp’s great-niece Silvia Boadella, translated from the German by the New Criterion contributor Tess Lewis, tells quite a different side of the story of this artist whose life and work confronted two world wars while remaining faithful to the promises and possibilities of modern art.2

The book is a welcome pendant to the exhibition, adding some warmth to the typical chilliness of a moma presentation. Boadella has written evocative vignettes of Taeuber-Arp’s “life through art,” inspired by family stories and the artist’s creative record. She begins with a retelling of Taeuber-Arp’s final night and her untimely demise: “Sophie lies very still, the white duvet pulled up to her chin. The smoke spreads more thickly. The fire in the stove goes out . . . ” As she is accidentally poisoned by carbon monoxide alone in a remote garden house, the book reads like a fever dream from the great beyond.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Four Spaces with Broken Cross, 1932, Oil on canvas, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris © CNAC/MNAM/Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY. Photo: Bertrand Prévost.

Indeed, Taeuber-Arp “lived” abstraction through an abbreviated life that was as interesting, in many ways more interesting, than the objects and designs she left behind. After all, she inhabited Europe’s foremost creative circles, traveling with Kurt Schwitters and Hannah Höch to the island of Rügen in Germany and with Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings to the Amalfi Coast. Interweaving artists such as Alexander Calder, Max Ernst, and Sonia and Robert Delaunay in addition to Taeuber-Arp’s own husband, this book does much to reanimate the excitement of her times and the energy of a life that, in contrast to this exhibition’s heavy-handed editing, included other creative souls.

This is what is ultimately missing from moma’s presentation. Yes, as the exhibition catalogue proposes in its “Directors’ Forward,” this modernist polymath was a “designer of textiles, beadwork, costumes, furniture, and interiors, as well as an applied arts teacher; dancer; architect, painter, sculptor; illustrator; magazine editor; gifted amateur photographer; and champion of abstract art.” We now have evidence of this and then some. Yet in its great effort to single out Sophie Taeuber-Arp—even (as the catalogue admits) “deliberately exclud[ing] the drawings and collages that her grieving widower posthumously identified as ‘duo’ ”—“Living Abstraction” takes the life out of the living. We are left with hundreds of creative fragments but, in the end, a still life in need of its golden thread.

“Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction” opened at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, on November 21, 2021, and remains on view through March 12, 2022. The exhibition was previously on view at the Kunstmuseum Basel (March 19–June 20, 2021) and Tate Modern, London (July 13–October 17, 2021).

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: A Life through Art, by Silvia Boadella, translated by Tess Lewis; Skira Editore, 224 pages, $39.95.