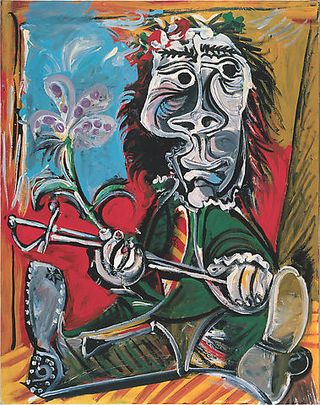

Pablo Picasso, Portrait de l’homme à l’épée et à la fleur (1969) © P.A.R. Photo by Marc Domage

THE NEW CRITERION

MAY 2009

Gallery chronicle

by James Panero

Stop the presses: the Gagosian Gallery has put on the best gallery show of the season, maybe the year. How could it be that this gallery, which for years epitomized the overindulgences of contemporary art, has mounted “Picasso: Mosqueteros”?[1] I shall discuss this momentarily. But first the show. This large exhibition in Chelsea of the paintings and prints of late Picasso is breathtaking. The Picasso biographer John Richardson has selected and arranged the work in the gallery himself. Many of the best paintings come from the collection of Picasso’s heir Bernard Ruiz-Picasso. The gallery has published a sumptuous catalogue with an extensive essay by Richardson on Picasso’s last years at his country estate of Notre-Dame-de-Vie in Mougins, on the French Riviera. (This being Gagosian, there is also a daft essay by the contemporary-art bogeyman Jeff Koons.) For those of us eagerly awaiting the final fourth volume of the Life of Picasso from the eighty-five-year-old Richardson, the catalogue is a tempting treat. But the show itself is the real feast. Here Richardson makes the case for the value of the last years of the artist’s life. As Picasso entered his tenth decade (he died in 1973 at the age of 91), he went into overdrive. His high-performance output “constituted a Great Late Phase,” according to Richardson, “one in which he felt free to do whatever he wanted in whatever way he wanted, regardless of correctness, political, social, or artistic.”

The press has been gushing over the show—and rightly so. It has been twenty-five years since the last (and the first) exhibition of the late paintings of Picasso came to New York. Enough time has passed that it is easy to forget we had many of the same discussions on the revelations of late Picasso a quarter of a century ago. Late Picasso is forever being rediscovered.

The 1984 Guggenheim show, organized by Gret Schiff and originally booked for the Grey Art Gallery at New York University, almost never saw the light of day. There was limited interest in the subject. A 1973 exhibition on late Picasso at the Palace of the Popes in Avignon was a summer flop. Robert Hughes called it “more process than product.” He also slammed the show with a one-line dismissal: “Picasso appeared to have spent his dotage at a costume party in a whorehouse.” The 1980s gave late Picasso a warmer welcome. During his lifetime, people had been “incinerated in the furnace of Picasso’s psyche,” as Richardson describes it. A decade after his death, the feminist reaction to the superman artist, following the 1964 publication of Françoise Gilot’s tell-all book Life with Picasso, had dissipated. Tastes were also changing. The bloom was off the rose of high abstraction. Picasso always “loathed” abstraction, according to Richardson. “He never painted an abstract painting and he wanted to make his painting even more representative.” By the 1980s the manic representational brushwork of Picasso’s fast and furious final years came to be seen as the harbinger of neo-expressionism.

In March 1984, Jed Perl wrote a definitive essay on the subject of late Picasso in these pages, titled “Picasso’s finale.” “In the 1950s,” he wrote, “Picasso seemed an old hedonist fading away in the glare of the Mediterranean sun. The work of the last five years reveals a very different man: the wisest bacchant of them all.” Hughes remained circumspect: “No exhibition in memory has been so full of eyes (or of anuses and genitals, his other fetish objects)… . Picasso’s last decade contains little that can compare with his work in the 30 years after 1907, when his transformation not only of modernist style but of the very possibilities of painting was so vast in scope, deep in feeling and authoritative in its intensity.” Both critics came to agree with André Malraux’s understanding of the artist in Picasso’s Mask (the title of Malraux’s 1974 book). “I must absolutely find the mask,” Picasso told Malraux.

The raffish cast of characters in Picasso’s final paintings represents the artist’s masked personae, avatars of his artistic ego and totems against death, a fifty-two-painting deck of death cards shuffled through the history of art. With his voluminous output, Picasso tried to deal every possible hand to the hangman. He was “so frightened of death—you could never mention his will to him,” says Richardson. Following surgery in the spring of 1966, Picasso never took a day off from painting, drawing, or printmaking. He constructed two additional studios at Notre-Dame-de-Vie to accommodate his production. In the last three years of his life alone, Picasso may have painted up to four hundred paintings. Richardson has discovered that around his ninetieth birthday Picasso painted six huge paintings in less than one week. The final years represented “an amazing burst of volcanic energy. He wanted to somehow assimilate the whole Western figurative tradition and Picassify it.”

The great relief comes from how Picasso chose to Picassify his own late work. Picasso’s bull-and-anus motif had grown tedious. His over-sexualization of the visual world had become a cartoon-like cliché, one urinal scrawl after another. The parade of battered wives in his portraits was also growing dreary, as Picasso himself came to recognize. Today’s blond beauty, everyone knew, would become tomorrow’s succubus, a vagina-dentata gorgon forever gnawing at Picasso’s pathetically vulnerable Andalusian arch masculinity. His daughter Paloma once remarked that “people were happy to be consumed by him. They thought it was a privilege.” Maybe so, but it grew increasingly unappetizing to watch Picasso consume his cannibalistic meals. He was that child-Titan forever licking his chops and showing his plate cleaned of limbs and noses.

The final years took a different turn. As Picasso became more housebound in Notre-Dame-de-Vie, he introduced new and various forms of visual stimulation. He projected Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, featuring the Amsterdam musketeers (the “Mosqueteros” of the Gagosian title), on his studio wall. He was a movie buff. He watched television. Picasso turned his attention away from reality, his personal sexual reality, reality as filtered through cubism and expressionism, and focused on these new influences. Rather than devour the lives around him, he began to chew on the more palatable (palettable?) legacies of Rembrandt, Velásquez, Goya, El Greco, and van Gogh.

Kenneth Clark has described a major artist like Picasso, burning through his final stage, as someone who paints in an “unholy rage.” On the surface, Picasso appeared to do just that. His furious production at Gagosian seems simply mad. But the show ends up oddly apollonian. Picasso was attempting to scare off death while at the same time diligently preparing the decor for his own pharaonic tomb. Compared to his earlier work, there is less visceral rage in these final paintings and more consistent energy. The Gagosian paintings are mainly enormous playing-card portraits of kings, jacks, and jokers popping up in a roll call of stock art-historical characters. The show is an Old Master museum hall perceived through Picasso-colored glasses.

“How could these unashamedly outrageous paintings,” Richardson asks, “with their farcical irony, their caricatural baroquerie, their glut of genitals, their science-fiction time warp and subversive black comedy, be reconciled to the accepted precepts of art history?” The answer is that these conservative paintings are pure art history, a survey course by the aging don offered up in titles like the Dutch-figured Tête d’homme du 17ème siècle de face (1967).

The show begins with Femme assise dans un fauteuil (1962). This turns out to be a straight portrait of Picasso’s mistress Jacqueline, the only one of its kind in the show. It is the earliest and most real work on view—different in a different way from the rest of the paintings. (The remaining exhibition is different in much the same way.) Portrait de l’homme à l’épée et à la fleur (1969) is a later standout, an interpretation of a Velásquez dwarf-portrait but here masked and wearing a flower in his hair (which Richardson believes to be a reference to hippie fashion).

Now for a word about the venue. Look closely at the provenance of one of the paintings and you will notice that Homme à la pipe (1968) is on loan from the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Collection. These are the same Cohens who put Damien Hirst’s shark in the Metropolitan Museum. They are collectors who have themselves become poster children for the overinflation of interest in terrible contemporary work. Their guide on this journey has been the gallery owner Larry Gagosian. In his catalogue essay, Gagosian writes, “The opportunity to present Picasso’s work in a contemporary gallery such as ours epitomizes just how relevant and thought-provoking his work continues to be today.” With seven high-profile galleries around the globe, Gagosian has an imperial understanding of promising markets, and he knows how to occupy them. He has applied his Midas touch to some of the most undeserving artists of our times. Late Picasso, far from undeserving, fits his bill of sale as well. The late period offers up a clutch of available work of similar quality by a name-brand artist, allowing for an inflation of comparable prices. So long as this translates into scholarly exhibitions free of charge, more power to him.

Finally, a word about an upcoming show in Connecticut.[2] The classical realist Edward Minoff has done for the seascape what Jacob Collins has accomplished with the figure. A former graffiti artist and professional cartoonist who has dedicated his life to classical art after meeting Collins in the late 1990s, Minoff has become a master of the breaking wave and an authority on the rolling surf. In his paintings, green translucent waves perfectly curl up in arcs and dips and ripples. Minoff grew up observing the beach at Fire Island, Long Island and continues to make his studies there: topographical studies of water and wind, color studies of misty sunlight at dawn, compositional studies of ideal moments of flood. He never works from photographs, one of the precepts of Collins’s schools and something that separates the work from photo-realism.

Until now Minoff has worked small, perfecting his seascapes over five years in jewel-like horizontal compositions. Starting last October, Minoff determined to take on a more epic seascape composition in the manner of Collins’s “Eastholm Project,” which I wrote about in June 2008. Along with several smaller paintings, including some poetic moonscapes, Minoff will be unveiling his eight-foot-wide painting, Waves, at Cavalier Galleries in Greenwich this month. I recently paid a studio visit to see Minoff apply the finishing touches. With his growing ambition and focused talent, Minoff is an artist to watch and enjoy.

Notes

Go to the top of the document.

- “Picasso: Mosqueteros” opened at Gagosian Gallery, West 21st Street, New York, on March 26 and remains on view through June 6, 2009. Go back to the text.

- “Edward Minoff” will be on view at Cavalier Galleries, Greenwich, Connecticut, from May 14 through May 28, 2009. Go back to the text.