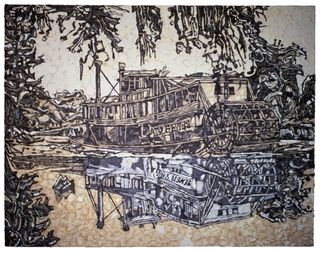

Joe Zucker Amy Hewes (1976), copyright: Joe Zucker, courtesy Mary Boone Gallery.

THE NEW CRTIERION

May 2010

Gallery chronicle

by James Panero

On “Joe Zucker” at Mary Boone Gallery, “Bruce Gagnier: Incarnate” at Lori Bookstein Fine Art & “Shirley Jaffe: Selected Paintings, 1969–2009” at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, “Lois Dodd: Second Street Paintings” at Alexandre Gallery & “Deborah Brown: The Bushwick Paintings” at Storefront, Brooklyn.

Joe Zucker was born in 1941 to a Jewish family on Chicago’s South Side, at a time when the Irish and Italian gangs of the area sparred over territories embroiled in black migration and white flight. He got out through varsity basketball and found a moment of jock glory on the squad at Miami University in Ohio. Yet Zucker also happened to be blessed with one of the more interesting minds in American art. This complicated his athletic career and his artistic one as well. Zucker has long been out of step with the dullness that has come to dominate contemporary artistic production.

In 1961, Zucker gave up playing basketball and returned to Chicago to enroll at the Art Institute, where he had been drawing in his spare time since the age of five. His teachers were thinking Braque and the School of Paris. Zucker was more interested in potboilers and the narrative art of Thomas Hart Benton. He passed through the Institute’s bachelor’s and master’s programs, and followed this up with a teaching stint in Minnesota. He arrived in New York in 1968, one of modern art’s more fruitful moments, when the avant-garde had just passed through the rabbit hole of minimalism and was beginning to re-embrace the craft and process of painting.

At the time, modernism’s recursive instinct seems to have reached its end-game. Minimalist art and sculpture had folded form back on itself to an infinite and emptying degree. Like other artists of his generation, Zucker used minimalist logic to structure his artistic practice, but he sought to expand this logic to maximal effect.

“You can be tempted into reducing and reducing to the point of emptiness, simply repeating terms dictated by the perimeter of the paint,” Zucker noted in an interview. “I wanted to breach the perimeter and get into the very substance of the painting. I saw that as a way of evading the self-defeating outcome implicit in the reductive logic of modernism.” By infusing his work with narrative and humor, Zucker charted out a singular artistic path.

From his graduate-school days, the subject of the painter’s canvas has been one of Zucker’s recurring interests. It was the material of oil, after all, that received the lion’s share of attention by the Abstract Expressionists. Taking a cue from the revival in weaving and craft-based art, Zucker turned this relationship around and moved the canvas to the foreground, from surface to subject matter. An early series of Zucker’s work consists of abstract weavings of colored strips, recalling the warp and weft of a painting’s canvas.

In the 1970s, Zucker developed work based on the “history of cotton,” which he first showed at New York’s Bykert Gallery, run by Klaus Kertess and Jeff Byers. A one-time assistant from the Bykert Gallery has now brought five of these large works back together for an important show. The fact that this assistant has become the mega-dealer Mary Boone may indicate her turn from the over-hyped painters of the 1980s to overlooked artists like Zucker, who came of age a decade before.[1]

Or maybe Boone is now turning to Zucker because this work from the 1970s appears to be the most politically charged of his career, and somehow relevant and palatable. On their face, these large canvases depict various sepia-toned scenes of the antebellum South: a paddle boat in Amy Hewes (1976); slaves and an overseer in Brick-Top, The Field Hand, and Lucretia Borgia (1976); bales of cotton stacked and hauled in Reconstruction (1976) and Paying Off Old Debts (1975); and the neoclassical facade of Old Cabell Hall in University of Virginia Law School (1976). Yet the layers of representation in Zucker’s cotton constructions complicate this single reading.

Zucker built his paintings through a self-invented process where craft, image, and logic came together in one worked-out puzzle. After dipping cotton in pigmented Rhoplex, a thick acrylic binder, Zucker applied the balls to canvas. The effect recalls pointillist brushstrokes frozen in high relief. By forming an image of its agricultural origin, the painting’s canvas becomes both medium and content, a work depicting its own history of production as much as the American past.

Just as minimalist logic can be air tight, even airless, Zucker’s systems risk closing up through their own hermetic seals. Zucker’s more recent work has consisted of drawings of container ships and pirates, constructed in various ways from rolls of canvas and paper, some illustrated, some literal, and all in need of unpacking. Zucker’s history of modernism has become Roger Fry by way of the Jolly Roger—a picture plane shot through with cannon balls.

The 1970s series stays more accessible by tapping into a main current of the evocative American narrative, when cotton was king. The rigor of Zucker’s flights of logic can still astonish. The craft that went into these works is remarkable to behold. Boone has done us a service by bringing together these history paintings that are a part of history, at a time when museums remain oblivious to the most important paintings of the living past.

Since Elie Nadelman first rubbed down the surface of his vernacular sculptures, modern artists have understood how the quality of an object changes through handling and care. Nicholas Carone has long been carving sculptures that resemble classical fragments, ones that could have spent some time at the bottom of Lago Maggiore. Such works have a sense of their own history sculpted right into them. The sculptures of Bruce Gagnier, whose art was recently on view at Lori Bookstein, show a similar physiognomy of neglect, maybe this time of self-neglect.

Some of Gagnier’s statues, like Seaman (the drowned sculpture) (2009), seem to have attracted barnacles while ingesting some brine. With mottled, raisin-like skin and distended bellies, other figures appear almost pickled, tipsy, as though their more uninhibited selves are showing through their classical skins. Gagnier molds each of his figures in hydrocal, a plaster-like medium, then applies a finish of pigment and wax. The unique surface treatment leaves the work with a worn, marble-like sheen.

Granted, these sculptures can be more than a little creepy. I am not sure I would want to share a studio apartment with one of the life-sized works—but I wouldn’t mind a visit. Odd figures have tales to tell.

The painter Shirley Jaffe is eighty-six-years young and has been a fixture in Paris for over half a century, yet the work of this native New Yorker can still be new to the American public. So much the better for us, as we get to discover her again and again. Following its exhibit at The Art Show earlier this year, Tibor de Nagy last month launched its third exhibition of Jaffe’s work with a survey from the last thirty years.[2]

Jaffe has led a career in reverse. The oldest work in the show, the hard-edged arrangement of The Gray Center (1969), is a mature construction of color planes and gentle surfaces. Jaffe’s more recent work, by contrast, shouts youthful indiscretion. In Hop and Skip (1987), Jaffe tossed those earlier, mature color planes sky-high and captured them mid-flight. Hard-edged confetti now spirals and twists against a white background.

The more the paintings open up, the more energy Jaffe manages to contain in them, even when hints of bricks and roofline pop through, as in the “New York Collage” series of 2009. The result, a mix of hard-edged color theory and expressionist line, has a comic boldness that seems both of the moment and for the ages, fresh and timeless.

For the past several years, Alexandre Gallery has been regularly showing Lois Dodd’s gem-like scenes of Maine, often oil on masonite measuring at most two feet square. This past month, Alexandre brought together a selection of Dodd’s older work matched with two recent cityscapes of the same scene painting over forty-years on.[3]

When Dodd first painted the city view from her studio window in the 1960s, she brought a hard-edged sensibility for structure and line to the urban scene. The highlight of this period on view at Alexandre was Men’s Shelter, April (1968). In this large oil on canvas, an ordinary back window opens to a geometry of rooflines, colors, and shadows, which come together like an abstract jigsaw puzzle. Planes of color edge up against each other and seem to pulsate from their edges.

Over several images, Dodd depicted the same scene at different times of day and different seasons. In another series from the same period, she captured the garden view from her apartment in April, October, and a foggy day in February.

When Dodd returned to this same “Second Street” view from her window many years later, she brought her growing lyrical sensibility. In the two works from 2009, hard edges gives way to color and fullness, as though the urban landscape has entered full bloom.

I wrote about the painter Deborah Brown three months ago in my survey of Bushwick and its new Storefront gallery. Brown’s urban skyscape was the show-stopper of this gallery’s inaugural group exhibition. Now a solo show of her recent work is on view in this vital little space.

Unlike many of her Bushwick colleagues, Brown arrived in this neighborhood as an established mid-career artist, but she quickly tapped into the community’s youthful, shared experience. Her lush representational work, which regularly shows at Lesley Heller Gallery in Manhattan, has often depicts flora and fauna. In Bushwick, Brown found an urban contrast in industrial ruin and natural growth.

In “The Bushwick Paintings,” her latest series, an accretion of vines and wires, flowers and fences vies against a background of factory towers and enveloping skies. The images glow through scrims of pigment, which bathe the atmosphere in vibrant reds and greens. Brown finds renewal out of the blight of a ruined landscape. Her vision, which comes out of Romantic sensibility, reflects the spirit of this rough landscape and the artists who now share it.

Notes

Go to the top of the document.

- “Joe Zucker” was on view at Mary Boone Gallery, New York, from March 25 through May 1, 2010. Go back to the text.

- “Bruce Gagnier: Incarnate” was on view at Lori Bookstein Fine Art, New York, from March 31 through May 1, 2010. Go back to the text.

- “Shirley Jaffe: Selected Paintings, 1969–2009” was on view at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, from March 11 through April 24, 2010. Go back to the text.

- “Lois Dodd: Second Street Paintings” was on view at Alexandre Gallery, New York, from March 31 through May 1, 2010. Go back to the text.

- “Deborah Brown: The Bushwick Paintings” opened at Storefront, Brooklyn, on April 2 and remains on view through May 16, 2010. Go back to the text.