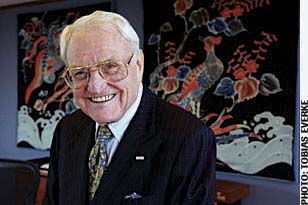

Philanthropist Lewis B. Cullman says "release the pot of gold."

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

August 20, 2010

The Best Way to Really Give Away Money

by James Panero

Private foundations tend to sit on their pots of gold. They should be spending them down more.

When 40 of America's richest individuals signed the "giving pledge," a challenge set by Warren Buffett and Bill and Melinda Gates to donate half of one's wealth to charity, at least one philanthropist was not impressed. "My opinion is: So what?" says Lewis B. Cullman.

With a record of giving that extends in the hundreds of millions and throughout New York's cultural institutions, Mr. Cullman, who is 91, is alarmed by how the money donated to charity by the very wealthy usually ends up. Locked, he tells me, in private grant-making foundations that may only release a trickle of the billions of dollars squirreled away inside.

Mr. Cullman's argument gets to the heart of the different ways Americans donate to charity. Most of us write donation checks directly to needy causes. Those with greater means set up private grant-making foundations, which hold nearly tax-free assets in endowments—and often give away as little as the government allows.

Under current tax law, private foundations are only required to spend 5% of their endowment per year. Twenty percent of that may go to operating expenses. Since endowment investments historically earn more than what they must give out, foundations may never need to dip into their principal assets, yet are able to feed their own administrative bloat in perpetuity.

Mr. Cullman believes their recent track record proves that private foundations exist primarily for their own self-perpetuation. In the last year, during the economic downturn, many foundations cut their rate of giving because of losses in their endowments. Based on a survey of more than 1,000 foundations, the Foundation Center estimates an 8.4% drop in giving for 2009, in inflation-adjusted terms, the steepest yearly decline since the center began its tracking in 1975.

For Mr. Cullman, this decline in giving in a time of acute need means that foundation administrators are more concerned about the size of their nest-eggs than about their philanthropic mission. He says that foundations should have "released the pot of gold" and increased their donations, even if that means cutting considerably into their endowments.

To force them to action, Mr. Cullman believes, the mandated annual payout rate should be increased from 5%; or foundations should be required to enact "sunset clauses," for spending down their assets in an established time frame. His position, spelled out in his book, "Can't Take It With You," has not made him popular in the world of foundation management. When he mentioned the premise to Vartan Gregorian, president of the Carnegie Corporation, he "almost dropped his glass," Mr. Cullman recalls. "'My God,' he laughed. 'You'll put me out of business.'"

In certain cases, going out of business might make sense. "Many foundations start out with the best of intentions," says Rick Cohen, national correspondent for Nonprofit Quarterly magazine, but "over time they tend to stagnate." Even foundations with built-in sunsets (the Gates Foundation has a 50-year spend-down) are not necessarily protected from administrative top-heaviness.

In the 1920s, Julius Rosenwald, the chairman of Sears, Roebuck & Co., first raised the alarm about foundation bureaucracy. While nothing in the law prevents private foundations from spending themselves out of existence, few big ones do. The Aaron Diamond Foundation was one example in the 1980s, giving away $50 million to AIDS research. The influential conservative John M. Olin Foundation recently completed its own spend down, put in place to prevent ideological drift.

Despite these exceptions, little ever changes in the broad landscape of foundation policy, and the cure may be as bad as the disease. "These are private organizations that ought to have control of the money," warns Leslie Lenkowsky, professor at the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University. Sunset clauses, if government mandated, may have "unintended consequences," he says, and can not guarantee the money is used most effectively.

Even with diminishing resources of their own, many foundations are already working tirelessly to help their beneficiaries confront the economic downturn. Most experts agree that bad economic times call for increased giving by philanthropic organizations. "We ought to make the payout rule more flexible," says Mr. Lenkowsky. "In down times it should go up. In good times it should go down. It should be a counter-cyclical rule." Adds Rick Cohen: "They have endowments that are rainy-day funds. This is the time to tap them."

According to Fortune magazine, if every member of the Forbes 400 list followed the Gates "giving pledge," the total would be $600 billion--equal to the assets currently in private grant-making foundations. Should these perpetual monuments to yesterday's donors make their own giving pledge and spend down their endowments?

Just ask Lewis Cullman: "When you set up a family foundation and turn it over to bureaucrats, it is not human nature to vote yourself out of existence. It's time to end that, for the good of us all."