"Discovering Columbus," an installation by Tatzu Nishi featuring the 1892 Columbus Circle statue by Gaetano Russo. (All photographs by James Panero)

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

September 25, 2012

A Monumental Problem

by James Panero

Through late November, visitors to the southwest corner of Central Park will have to say "Goodbye, Columbus." That's because Gaetano Russo's 1892 statue of the explorer, usually visible for miles around, will be covered in scaffolding that all but removes the monument from public view.

The Columbus Circle monument covered by "Discovering Columbus"

What looks like restoration work is really much more: A Japanese artist, Tatzu Nishi, has been commissioned to decorate an elevated shed enclosing the statue so that, instead of looking out over Columbus Circle atop a 60-foot column, Columbus now appears to be standing on a coffee table, surrounded by couches, lamps, a television set, red window curtains and pink-and-gold wallpaper printed with pictures of Marilyn Monroe, Mickey Mouse and Michael Jackson. Admission to this spectacle is by a free timed ticket, with at most 25 people at once allowed inside the 800-square-foot space.'Discovering Columbus' encloses the explorer's statue at Columbus Circle in an 800-square-foot living room.

Marilyn Monroe, Mickey Mouse and Michael Jackson: custom wallpaper covers the "living room" of "Discovering Columbus"

The installation, "Discovering Columbus," has been produced by the Public Art Fund, a nonprofit championed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Dedicated to offering the public "powerful experiences with art and the urban environment," the fund's other projects have included bringing Jeff Koons's topiary-puppy sculpture to Rockefeller Center and Rob Pruitt's statue of Andy Warhol to Union Square.

Like much of what the Public Art Fund promotes, "Discovering Columbus" can seem like campy fun—a million-dollar confection brought to you by the city's billionaire mayor. Yet the hijinks of "Discovering Columbus" come at the expense of the Columbus Circle monument itself, which must be kidnapped to take part in the party. The offer of the organizers to restore the monument at the end of the show—with Parks Department funds—implicitly acknowledges the disservice done during the run.

A television inside "Discovering Columbus" is tuned to CNN

The temporary hijacking of Columbus Circle is but the latest chapter of a monumental problem. Part of this story is the unease, bordering on contempt, with which cultural progressives regard traditional monuments. Outmoded in both form and content, Columbus Circle was ripe for ridicule. Even if most New Yorkers find little fault with it, this classical monument to a questionable figure in our history has become embarrassing to the city's cultural establishment. "Discovering Columbus" therefore appropriates and recasts it at the exact time of year when it is valued most. This Columbus Day, the Italian-American groups that traditionally lay a wreath at the base of the monument can lean it against a purple sofa in Mr. Nishi's ersatz living room.

As power changes and the memorialized fall out of favor, the forces of history have destroyed monuments almost as fast as they go up. The cultural war on monuments, however, only officially began in 1871. That was the year Gustave Courbet, the celebrated Realist painter then in his early 50s, found himself at the center of a 72-day utopian experiment known as the Paris Commune. This failed attempt at autonomous rule became the model for many later idealist uprisings, from Soviet Communism to the student riots of 1968 to Occupy Wall Street. "For Courbet, the Commune was, all too briefly, the fulfillment of his dreams of a government without oppressive, domineering institutions, the Proudhonian Utopia of social justice come true," explains the art historian Linda Nochlin in her book "Courbet."

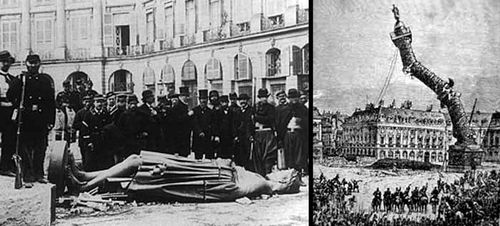

Paris Communards pull down the Vendome Column, 1871

As head of the Commune's Federation of Artists, Courbet quickly suppressed the city's traditional art schools: the Academy, the École des Beaux-Arts, and the Schools of Rome and of Athens. He then turned his attention to the Vendôme Column, a monument modeled after Trajan's Column in Rome that Napoleon had erected at the center of Paris to memorialize the French victory at Austerlitz. Courbet derided it as a "mass of melted cannon that perpetuates the tradition of conquest, of looting, and of murder." The Commune agreed and set about undermining its foundation and pulling it down with cables. As a band performed for an assembled crowd, the column came crashing to the street, breaking into several pieces. Three years later, after the collapse of the progressive Commune and the restoration of a traditionalist government, the French courts fined Courbet in exile to pay for the column's restoration. As his assets were seized and sold at auction, Courbet drank himself to death.

Following Courbet, the monumental fight between progressives and traditionalists hasn't gone much better. In the case of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial, now planned for Washington, a progressive design has faced a traditionalist backlash. In what critics have called a closed selection process, the Department of the Interior, working through the General Services Administration, chose the architect Frank Gehry to undertake the design for a 4-acre site on Independence Avenue. Rather than a classical design in line with the Jefferson and Lincoln memorials, Gehry proposed a progressive design that he said would seize on Eisenhower's modesty. It would feature a small statue of the president as a young boy sitting under 8-story-tall wire screens painted to resemble pictures of his childhood home in Abilene, Kan.

Frank Gehry's initial design for the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial

A traditionalist group called the National Civic Art Society has led a campaign to scrap the plan. Its Chairman, Justin Shubow, has testified before Congress against it. Léon Krier, a traditionalist architect and leading critic, has called Mr. Gehry's plan "An anti-monument if there can be such a thing." The antimonumentality of the design is no accident. Writing in the Washington Post, the architecture critic Philip Kennicott defended Mr. Gehry's design for inverting "several of the sacred hierarchies of the classical memorial, emphasizing ideas of domesticity and interiority rather than masculine power and external display." But he goes further, praising Mr. Gehry for having "'re-gendered' the vocabulary of memorialization, giving it new life and vitality just at the moment when the old, exhausted 'masculine' memorial threatened to make the entire project of remembering great people in the public square seem obsolete." Ridiculous as this may sound, Mr. Kennicott's essay nonetheless serves a useful purpose in laying out the postmodern perspective on memorials. In his view, the purpose of the contemporary monument is antiheroic: to debunk, diminish and ensure that equal time is given to the subjects' more mundane qualities.

Progressives want monuments to be radical. Traditionalists want monuments to be classical, arguing that anything newer becomes a monument to radicalism and its designer rather than the people who are memorialized. Unfortunately, most of us get caught in the middle. We don't care about "regendering" our supreme allied commander in Europe and 34th president. At the same time, we may find the neoclassical design of the National World War II Memorial by the Austrian-born Friedrich St. Florian, or the new memorial to Martin Luther King Jr by the Chinese artist Lei Yixin, uninspiring.

Monuments give form to memory. They allow us to reflect upon our history, values and experience. Unfortunately, we no longer share a consensus on what that history, those values and that experience should be. We barely agree on what we should remember rather than forget, and we share no common understanding of what form our memories should take. That all helps explain why neither the progressives nor the traditionalists excel at monument design on their own—and why the bad designs and the ridicule of monuments seem bound to continue.

A version of this article appeared September 25, 2012, on page D5 in the U.S. edition of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: A Monumental Problem.