Interior of the 1913 Armory Show

THE NEW CRITERION

February 2013

Hogwash, abstract & the rest: an exchange

It mystifies me that, continuing under the editorship of Roger Kimball as previously under that of Hilton Kramer, The New Criterion persists in intermittently admiring in the visual arts the very decline and fall of culture that it so well and rightly militates against in government, politics, theater, music, and the media. Not seven pages after the editor, in his obituary “Jacques Barzun, 1907–2012” (The New Criterion, December 2012), gives with one hand by approving of Jacques Barzun’s apt indictment of the modern art scene—“ ‘When people accept futility and the absurd as normal, the culture is decadent’ ” and suffers “a progressive loss of resistance to humbug”—James Panero takes away with the other hand in a review that sets up the Armory Show (“The Armory Show at 100”) as embodying the work of “like-minded souls who helped nurture and propagate a renewed vision for culture.” “Renewed vision for culture”? Whom is he kidding? The Armory Show itself was the beginning of that end of art of which even The New Criterion disapproves.

Though Panero seconds Barzun in objecting to the present-day “professionalized museum class [that] dictates the story of art to an increasingly passive public,” he praises the “energy” of the Armory Show, which consisted of what he calls a “resurgence in art [that captured] the vital spirit of the times” in revolt against “the dry bones of a dead art.” He fails to see the modern decay as the inevitable fruit of the deracination set in motion by the radically revolutionary Armory generation. Is it now possible to deny that Mondrian, Kandinsky, Brancusi, and Duchamp have led the art troops onward and downward inevitably through Pollock, Moore, and Warhol to the present-day depravities that Barzun rightly deplores? Does a legitimate critique of late nineteenth-century academic formalism require Panero to lionize the Armory as a “vital” reaction to it when the show, despite displaying some works admittedly excellent of their kind, initiated the long succession of spiritually empty self-absorptions marching toward oblivion—abstract expressionism, pop, op, conceptual art, postmodernism, and blah, blah, blah?

Look, we’re all fighting losing battles here, complaining of a decay of culture that no amount of complaining but only vision could counteract, and there is no secret storehouse from which vision might be stolen. It comes, like the inspiration of the muse, in its own time in its own mysterious way. But can’t we at least get together in The New Criterion and agree that the extravagant claims for twentieth-century abstract art and the rest were hogwash?

Gideon Rappaport, Ph.D.

San Diego, California

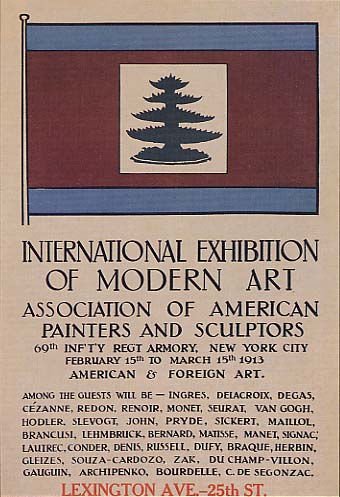

Armory Show poster, 1913

Dr. Rappaport, Ph.D., is entitled not to like “twentieth-century abstract art and the rest,” just as an admirer of Mozart may find distasteful the innovations of Beethoven. This is true even as some of us believe, as I do, that modern forms of aesthetic experience, rather than contributing to the “decline and fall of culture,” can in fact offer comfort, reflection, and beauty that mitigate against this decline.

Dr. Rappaport is not entitled to insinuate, however, that his particular taste should dictate ours, or, worse, that a reductive reading of history should dictate to us all. The New Criterion is a magazine about critical distinctions. This is why we can identify differences among “Mondrian, Kandinsky, Brancusi, and Duchamp . . . through Pollock, Moore, and Warhol” in a way that Dr. Rappaport seems unable to do. We will furthermore defend these critical distinctions from the mindsets that see artistic achievement only in black and white.

On the subject of the 1913 Armory Show: It says something about this particular achievement that the discussion of modern art it inspired continues today. We may come down on different sides of the conversation, but I hope we can agree with the Armory’s mission statement: “We do not believe that any artist has discovered or ever will discover the only way to create beauty.” For this reason we should consider art broadly and find the joys in its contemplation.