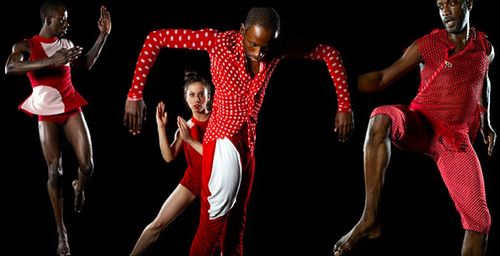

Reggie Wilson/Fist & Heel Performance Group, "Moses(es) Moses(es)"

James writes:

Timed to its annual conference, the Association of Performing Arts Presenters recently came to town and with it a "convergence of a dozen major performing arts industry forums and public festivals," which it called "January In NYC." These showcase performances ran the gamut from opera to chamber music to jazz. For those who follow dance, the Joyce Theater organized the first of what it promised would be an annual "American Dance Platform,” sponsored by the Harkness Foundation for Dance, this year curated by Paul King and Walter Jaffe of Portland's White Bird dance festival.

With eight companies paired up in four programs spread over the week, American Dance Platform matched the Martha Graham Dance Company with the Reggie Wilson/Fist and Heel Performance Group for two performances. The pairing made sense. Both New York-based, the two companies use the modern dance forms of successive generations to explore stories of origins, mass movement, and mythology: Graham as the great innovator of twentieth-century dance, most famously in Appalachian Spring; Wilson as a well-known choreographer now working in the twenty-first.

But differences more than similarities were on view at the Joyce for this double bill, as Wilson benefited from the fresh energy of a company at work with an active founder, while Graham wrestled with the challenges of a company contending with the long shadow of its departed mentor, who died in 1991.

As the leader of his Fist and Heel Performance Group, named after a derisory term for the drum-less dance forms of the African diaspora, Wilson was ever-present. “Moses(es), Moses(es),” a dance that has recently been performed at Jacob’s Pillow and other venues in various forms, filled the program. Wilson began by stepping onto stage, not as a dancer but more as a silent narrator, telling his story through his company’s movements. He distributed candy to a few chairs in the first row and swept a path through a pile of tinsel reminiscent of foamy water at the center of the stage, which his dancers then traversed as they introduced themselves to the audience. For most of the rest of the performance, Wilson sat on folding chairs observing and clapping from a corner of the stage, putting a personal frame around this narrative performance while setting it up as an evolving work in progress.

The opening image of parting waters set the stage, so to speak, for Wilson to merge the story of Moses and the Red Sea with the travails of the Middle Passage, mixing the history of Jewish and Black enslavement in a constant swirl of singing and movement. Drawing a line between ancient and modern forms, at one time Moses(es) might recall Egyptian hieroglyphics, at another the “Soul Train” line dance.

In this historically Afro-Caribbean dance troupe, where some seasoned members have been in company nearly since its founding in 1989, such as Rhetta Aleong ('92), Lawrence Harding ('93), and Paul Hamilton ('99), the relatively recent addition of Anna Schön, a young and dynamic Jewish dancer, spoke to the shared histories of Wilson's diaspora story, and what Wilson calls “the many iterations of Moses in religious texts, and in mythical, canonical and ethnographic imaginations.” Reminiscent of Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer, Schön herself has had to navigate between the worlds of the orthodox yeshiva and modern dance.

Martha Graham Dance Company, "Steps in the Street"

After the intermission, Janet Eilber, the longtime Artistic Director of Martha Graham, introduced her program by thanking Wilson for upping “our cool factor." Well intentioned, the comment nevertheless came off as superficial and tone-deaf, eliciting groans from the audience—and foreshadowing the production to follow.

I have commented many times on the substandard quality of recorded music at live performances. A well-known maestro recently told me he walked out of a holiday performance of “Lord of the Dance” on Broadway because of the music’s overamplification, only to find that the ushers had ear plugs at the ready to distribute. (Too bad they didn’t also have eye masks to give out.)

For “Steps in the Street,” an anti-war dance from 1936, Martha Graham animated her company into attacking phalanxes, at times moving in zombie-like lockstep, at times paralyzed by their own spiritless inertia. The brassy score is by Wallingford Reigger, and the recording used at the Joyce sounded as old as the dance itself, with low fidelity that did little to help the true fidelity of this live performance. Both shrill and muffled, the recording washed out the dance’s essential sharp movements. It would be truer to Graham’s vision to employ recordings up to modern standards, even if that means revisiting original scores.

For "Lamentation Variations," Eilber continues her initiative of commissioning contemporary choreographers to create work inspired by "Lamentation," Graham’s 1930 solo work. At the Joyce, we were presented with a recording of Graham explaining “Lamentation” along with an original film of the dance projected onto the stage (again, in desperate need of remastering). The company then performed “variations” by the contemporary choreographers Bulareyaung Pagarlava, Sonya Tayeh, and Larry Keigwin. The Graham history lesson was much appreciated, but whether a comment on the singularly of Graham or the quality of contemporary choreography (or some combination of the two), none of these works came close to the skin-crawling, visceral feel of Graham’s original dance, settling instead for decorousness (Pagarlava), histrionics (Tayeh), and distance (Keigwin). At the Joyce, we were fortunate to see these programs through the showcase of Dance Platform, but one takeaway is that the vitality of Graham needs no variation.